Abstract

Depression is the most common mental illness in the elderly, and cost-effective treatments are required. Therefore, this study is aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of a mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) on depressive symptoms, mindfulness skills, acceptance, and quality of life across four domains in patients with late-onset depression. A single case design with pre- and post-assessment was adopted. Five patients meeting the specified inclusion and exclusion criteria were recruited for the study and assessed on the behavioral analysis pro forma, geriatric depression scale, Hamilton depression rating scale, Kentucky inventory of mindfulness skills, Acceptance and Action Questionnaire II, The World Health Organization quality of life Assessment Brief version (WHOQO-L-BREF). The therapeutic program consisted of education regarding the nature of depression, training in formal and informal mindfulness meditation, and cognitive restructuring. A total of 8 sessions over 8 weeks were conducted for each patient. The results of this study indicate clinically significant improvement in the severity of depression, mindfulness skills, acceptance, and overall quality of life in all 5 patients. Eight-week MBCT program has led to reduction in depression and increased mindfulness skills, acceptance, and overall quality of life in patients with late-life depression.

Keywords: Cognitive-behavior therapy, late-life depression, mindfulness

INTRODUCTION

Depression has been found to be the most common illness of old age in India and is considered to be the most important cause of misery in late life.[1,2] Late-life depression (LLD) also carries additional risk for suicide, medical comorbidity, disability, and family caregiving burden.[3]

Studies have shown psychological interventions for LLD to be efficacious, especially cognitive and behavioral approaches.[4,5,6,7,8] Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) developed by Segal et al. is an 8-week program that combines training in mindfulness meditation, following the approach developed by Kabat-Zinn, with interventions from cognitive behavioral therapy that have been used successfully in the treatment of depression in young adults.[9,10] MBCT or other mindfulness-based interventions have been successful in treatment and relapse prevention of depression in young adults so far.[11,12,13,14,15]

Very few studies have examined brief therapies for the treatment of LLD in the Indian context particularly application of cognitive behavior therapy and mindfulness-based approaches. Therefore, this study is an initial attempt to study the effects of MBCT on persons with LLD, in the Indian context.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A single case design with pre- and post-therapy assessment was adopted. Six clients with an International Classification of Diseases Tenth Edition (the World Health Organization, 1992) diagnosis of the major depressive disorder, mild to moderate depressive episode (F32), were recruited from the outpatient mental health services of NIMHANS, Bangalore. Clients with serious medical conditions, dysthymia, severe depression with psychotic symptoms, psychosis and other primary psychiatric disorders, current psychoactive substance use, neurological conditions, residing in homes for the aged, and those who had undergone psychological intervention in the previous 1 year were excluded from the study. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the protocol Review Committee of the Department of Clinical Psychology for technical and ethical purposes. Written informed consent was obtained from the clients, participation was voluntary, participants were free to withdraw from the study at any time without any adverse effect on other ongoing treatment, and no incentives were offered.

Tools

A sociodemographic and clinical data sheet were developed for this study and used to gather information about the client's and their illness. Behavioral analysis pro forma was used to assess specific behaviors in various areas including antecedents, historical, social, cognitive and biological factors, and to formulate each case from a cognitive behavioral perspective. Geriatric depression scale (GDS) and Hamilton depression rating scale (HDRS) were used to assess depression.[16,17] Mindfulness skills and psychological flexibility were assessed by the Kentucky inventory of mindfulness skills (KIMS) and Acceptance and Action Questionnaire II (AAQ II), respectively.[18,19] The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment Brief version (WHOQOL-BREF) was used to measure the quality of life across four domains namely physical, social, psychological, and environmental as well as overall quality of life.[20] Meditation practice pro forma was developed for the study to monitor the time spent by participants on the home practice of mindfulness meditation, and intervention feedback pro forma was developed to obtain qualitative information from the participants regarding changes they have felt subsequent to the therapy, and patient's experiences from the same have been reported.

Procedure

Therapeutic program

The therapeutic program consisted of 8 weekly sessions delivered in an individual format, each session lasting for approximately 90 min. During the initial sessions, clients were educated about depression and the concept of mindfulness. They were instructed to practice mindfulness through body scan meditation and during one routine activity to come out of the automatic mode. During the middle phase, mindfulness of breath and sitting meditation were taught to the clients along with recognizing negative automatic thoughts. Clients were taught to treat thoughts, not as facts, but as passing mental events and to skillfully observe and “let them go.” The thoughts, feelings, and bodily sensations associated with pleasant and unpleasant events were focused on, and homework exercises were given for clients to incorporate mindfulness in their daily lives.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

Mr. S.S., was a 52-year-old married male, Hindu, from upper socioeconomic status, hailing from an urban background, educated up to B. Com., and self-employed as a businessman. His chief complaints were of sad mood, decreased sleep, fatigue, and anxiety over business, indecisiveness, in addition to the loss of pleasure and decreased libido and appetite, and significant weight loss. The family history of depression in maternal uncle was reported, and client reported currently having supportive family environment. Premorbidly, client appears to have anankastic traits, and perfectionistic beliefs. He was evaluated and diagnosed with moderate depression without somatic symptoms incomplete remission and was prescribed escitalopram 100 mg, and referred to the behavioral medicine unit for the management of depressive symptoms. Posttherapy, client reported increased awareness, increase in happiness as well as productivity. He also reported decrease in perfectionism in his behavior, especially other-oriented perfectionism. Breathing space was reported to be most helpful by client as he could practice it anywhere in a short amount of time.

Case 2

Mr. S.M. was a 61-year-old married male, Hindu from upper socioeconomic status educated up to C.A., currently working as a volunteer at a foundation, from an urban background. His chief complaints were those of sadness of mood, decreased interest in activities, feeling tired and lethargic, and forgetting things. Client perceived others as being hostile toward him, viewed himself as a failure and experienced jerking of the head and burping whenever stressed. Difficulties in memory and sleep disturbances were also reported by the client. Disputes between client and his siblings had been present for more than two decades. Premorbidly, client appears to have been dominant, wanting things to be done in a particular manner, and suggesting anankastic traits in personality. A diagnosis of recurrent depressive disorder was made subsequent to the evaluation and prescribed mirtazapine 30 mg, and he was referred to the behavioral medicine unit for the therapy. Posttherapy, client reported increased awareness, increased activity levels, and being able to let go. Decrease in negative thoughts and somatic symptoms were also reported. Overall, client found the therapeutic program helped him in moving forward instead of remaining preoccupied. Though body scan meditation was found difficult by the client, he was able to practice sitting meditation with lesser difficulty.

Case 3

Mr. NKD was a 64-year-old widowed and separated male, Hindu from middle socioeconomic status educated up to M.A., retired officer from government service, from urban background. His chief complaints were of sadness of mood, crying spells, withdrawn behavior, decreased interest in activities and feeling tired, and lethargic. His sleep was disturbed, and his appetite had also decreased. Client was estranged from his family of origin as well as the family of procreation and would often ruminate over it. A diagnosis of recurrent Depressive Disorder was made subsequent to the evaluation, and he was prescribed fluoxetine 20 mg and referred for cognitive-behavior therapy to the behavioral medicine unit. According to the client, posttherapy he became more accepting, more nonjudgmental, and found meaning in life. He reported that he had lowered expectations from others which had resulted in lesser anger. Even after an accident and being in great physical pain, client reported his discomfort was less. The patient reported difficulties in practicing mindfulness meditation regularly but was more successful with mindfulness practice incorporated in daily activities.

Case 4

Mr. R.R. was a 58-year-old married male, Hindu from middle socioeconomic status educated up to B. Com, retired clerk from textile mill, from urban background of Bengaluru. His chief complaints were of sad mood, suicidal ideas, lack of concentration, decreased interest in all activities, and anxiety about self, family, and future for past 4 years, following a financial loss and increased for last 1 year. Decreased interest in activities, sleep and appetite, were reported along with significant weight loss. Client has reported not feeling attached to parents or siblings due to his sibling being given preferential treatment by parents, and even currently prefers not to socialize with extended family. Client was evaluated and diagnosed with Moderate Depression without somatic symptoms was made, and he was prescribed Venlafaxine 225 mg and lorazepam 1 mg and was referred for cognitive behavior therapy for management of depression. Posttherapy, client reported increased energy and happiness and decrease in somatic symptoms.

Case 5

Ms. R.D. was a 52-year-old married female, Hindu from middle socioeconomic status educated up to BA, housewife from urban background presented with complaints of sad mood, crying spells, suicidal ideas, lack of concentration, decreased interest in all activities, anxiety about self, family, and future. This was precipitated by exacerbation of the illness of client's daughter and her ruminations about the future of her family. Premorbidly, client was reported to be sociable, but sensitive to criticism. A diagnosis of moderate depression without somatic symptoms was made subsequent to the evaluation, and she was referred for cognitive-behavior therapy to the Behavioral Medicine Unit. Increase in acceptance and relaxation was reported by the client while self-criticism and suicidal ideas had decreased. Initially, client reported difficulties in meditation but with practice, reported finding it easier with time.

Statistical analysis

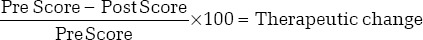

Statistical analysis was carried out on the five participants. Clinically significant changes (50% and above) based on pre- and post-therapy data were used to assess the efficacy of the therapeutic intervention.[21] Using this formula, the percentage of change between pre- and post-therapy points was calculated.

RESULTS

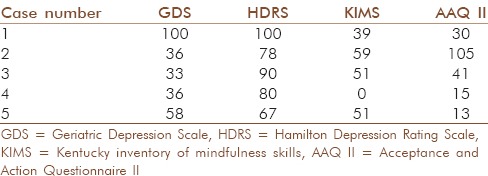

As seen on Table 1, both subjective and objective measures of depression were used to assess the levels of depression in this study. GDS is a self-rated measure of depression which showed improvement for all five patients, minimum being 33% and maximum being 100%. HDRS, a clinical rated measure showed improvement for all five patients ranging from 67% to 100%.

Table 1.

Improvement percentage in Geriatric Depression Scale, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills, and Acceptance and Action Questionnaire II scores for all clients

KIMS to measure mindfulness skills showed improvement in mindfulness skills for four out of five patients, minimum 39% being and maximum 59% [Table 1].

Psychological flexibility was measured by the AAQ II, which has shown improvement in all five patients ranging from 13% to 105% [Table 1].

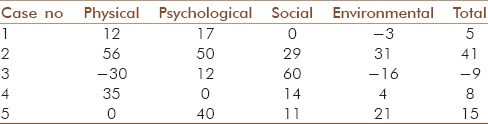

Table 2 shows the changes in quality of life across different domain following MBCT. Three out of five patients showed improvement in physical quality of life ranging from 12% to 35%; one patient showed no change and one patient has shown deterioration. In the psychological domain of quality of life, four out of five patients have shown improvement minimum 12% being and maximum 50%, with one patient showing no change. Four out of five patients have shown improvement in the quality of life social domain ranging from 11% to 60%, with one patient showing no change. In the environmental domain of quality of life, three of out five patients have shown improvement ranging from 4% to 21% and two patients have shown deterioration. Overall, quality of life showed improvement for four out of five patients ranging from 5% to 51% and one patient showing deterioration.

Table 2.

Improvement percentage in World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment-BREF scores for all clients

DISCUSSION

The primary objective of the study was to examine the effects of MBCT in reducing depressive symptoms in clients with LLD. Depression was seen to improve in all the five cases as measured by the GDS and HDRS ranging between 67% and 100%. These findings are similar to various other studies where MBCT has been effective in reducing depressive symptoms.[22,23,24]

The results also indicated improvement in mindfulness skills from preintervention to postintervention assessment as measured by the KIMS. The results can be compared to the findings of previous researches who have reported significant improvement of mindfulness skills subsequent to 8-week of MBCT.[11,25,26] From the qualitative analysis of the clients’ responses on the Intervention Feedback Pro forma, the theme of “Awareness” emerged. This theme was related to the subthemes of skill of distancing from thoughts, being in the present moment, acting with awareness, and awareness of changes in thoughts and feelings. Thus, to substantiate the findings on the KIMS, the clients were observed to have improved mindfulness skills especially that of increased awareness, which in turn may have mediated the reduction in severity of depression.

Psychological flexibility in elderly following mindfulness-based cognitive showed enhanced acceptance in all 5 cases as measured by the AAQ II. These findings are similar with previous research findings which reported that 8-week of MBCT led to the development of good levels of acceptance and participants noticing changes in their way of thinking, of feeling, and in their relation with the others.[11,27,28]

Overall, quality of life and the domains of quality of life have been seen to improve in four out of five patients. One patient suffered a hip fracture due to a road traffic accident during the course of therapy and has shown deterioration on the overall quality of life and physical and environmental domains. Studies have also reported that following an MBCT course, significant improvements have been observed in mindfulness and emotional well-being, and increased mindfulness was found to be moderately and significantly associated with improved emotional well-being.[26,28]

All clients were able to understand the concept of mindfulness during the initial sessions but have reported difficulties in practicing mindfulness meditation outside sessions. However, by middle sessions, clients were able to develop the quality of being mindfulness during several situations and found it easier to practice mindfulness meditation. Overall, increased acceptance and being able to let go were reported by the clients as a consequence of therapy. Decrease in ruminations, discomfort, and somatic symptoms were also reported by the clients.

To conclude, subsequent to the 8-week of MBCT, clients diagnosed with late-onset depression were found to have reductions in the severity of depression, objective and subjective, improvement in mindfulness skills, especially awareness, improvement in acceptance, and in the quality of life. These findings are similar to finding of previous researches where MBCT program was found “extremely useful” in reducing depressive symptoms in a geriatric population group.[29]

The results of this study have limited generalizability because of the small sample size. Lack of a comparable control group and nonavailability of follow-up data also add to limitations of this study.

CONCLUSION

The present investigation is one of the first attempts made in India to study the effect of MBCT on late-onset depression. The results of this study implicate the role of the practice of mindfulness meditation in developing mindfulness skills, acceptance and improving the quality of life across domains of physical health and environment, psychological well-being, and social relations in clients with late-onset depression. Based on the reports of clients’ experiences, it can also be concluded that mindfulness training helps in increasing awareness and acceptance of inner experiences as well as environmental demands. In addition, decreased ruminations, and decreased somatic symptoms posttherapy have also led to increased happiness and increased energy and activity levels. This study contributes toward developing cost-effective interventions for depression in the Indian setting, especially applicable to the elderly.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nandi DN, Banerjee G, Mukherjee SP, Ghosh A, Nandi PS, Nandi S. Psychiatric morbidity of a rural Indian community. Changes over a 20-year interval. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:351–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.4.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murali MS. Epidemiological study of prevalence of mental disorders in India. Indian J Community Med. 2001;26:198–200. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreescu C, Reynolds CF., 3rd Late-life depression: Evidence-based treatment and promising new directions for research and clinical practice. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2011;34:335–55. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2011.02.005. vii-iii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson LW, Gallagher D, Breckenridge JS. Comparative effectiveness of psychotherapies for depressed elders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987;55:385–90. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.3.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scogin F, McElreath L. Efficacy of psychosocial treatments for geriatric depression: A quantitative review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:69–74. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma MP. Behavioural Intervention with the Aged Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation Submitted to Clinical Psychology Department, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Areán PA, Cook BL. Psychotherapy and combined psychotherapy/pharmacotherapy for late life depression. Soc Biol Psychiatry. 2000;52:293–303. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01371-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Influences of socioeconomic status, social network, and competence on subjective well-being in later life: A meta-analysis. Psychol Aging. 2000;15:187–224. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.15.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Segal ZV, Williams JM, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Depression: A New Approach to Preventing Relapse. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kabat-Zinn J. New York: Delacorte; 1990. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain and Illness. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mason O, Hargreaves I. A qualitative study of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression. Br J Med Psychol. 2001;74(Pt 2):197–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma SH, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: Replication and exploration of differential relapse prevention effects. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:31–40. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kenny MA, Williams JM. Treatment-resistant depressed patients show a good response to Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:617–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuyken W, Byford S, Taylor RS, Watkins ER, Holden ER, White K, et al. Relapse prevention in recurrent depression: Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy versus maintenance anti-depressant medications. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;6:966–78. doi: 10.1037/a0013786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manicavasgar V, Parker G, Perich T. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy vs cognitive behaviour therapy as a treatment for non-melancholic depression. J Affect Disord. 2011;130:138–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1983;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baer RA, Smith GT, Allen KB. Assessment of mindfulness by self-report: The Kentucky inventory of mindfulness skills. Assessment. 2004;11:191–206. doi: 10.1177/1073191104268029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bond FW, Hayes SC, Baer RA, Carpenter KM, Guenole N, Orcutt HK, et al. Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behav Ther. 2011;42:676–88. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Power M, Harper A, Bullinger M. The World Health Organization WHOQOL-100: Tests of the universality of quality of life in 15 different cultural groups worldwide. Health Psychol. 1999;18:495–505. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.5.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:12–9. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramel W, Goldin PR, Carmona PE, McQuaid JR. The effects of mindfulness meditation on cognitive processes and affect in patients with past depression. Cognit Ther Res. 2004;28:433–55. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jain S, Shapiro SL, Swanick S, Roesch SC, Mills PJ, Bell I, et al. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation versus relaxation training: Effects on distress, positive states of mind, rumination, and distraction. Ann Behav Med. 2007;33:11–21. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3301_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carmody J, Baer RA. Relationships between mindfulness practice and levels of mindfulness, medical and psychological symptoms and well-being in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. J Behav Med. 2008;31:23–33. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mckim RD. Rumination as a mediator of the effects of mindfulness: Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) with a heterogeneous community sample experiencing anxiety, depression, and/or chronic pain. Diss Abstr Int Sec B Sci Eng. 2008;68:7673. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Splevins K, Smith A, Simpson J. Do improvements in emotional distress correlate with becoming more mindful. A study of older adults? Aging Ment Health. 2009;13:328–35. doi: 10.1080/13607860802459807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cebolla MA, Barrachina MT. Effects of mindfulness based cognitive therapy: A qualitative approach. Apunt Psicol. 2008;26:257–68. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McBee L. New York: Springer Publications; 2008. Mindfulness-Based Elder Care A CAM Model for Frail Elders and Their Caregivers. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith A. Clinical uses of mindfulness training for older people. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2004;32:423–30. [Google Scholar]