Abstract

When fabricating magnetic memories, one of the main challenges is to maintain the bit stability while downscaling. Indeed, for magnetic volumes of a few thousand nm3, the energy barrier between magnetic configurations becomes comparable to the thermal energy at room temperature. Then, switches of the magnetization spontaneously occur. These volatile, superparamagnetic nanomagnets are generally considered useless. But what if we could use them as low power computational building blocks? Remarkably, they can oscillate without the need of any external dc drive, and despite their stochastic nature, they can beat in unison with an external periodic signal. Here we show that the phase locking of superparamagnetic tunnel junctions can be induced and suppressed by electrical noise injection. We develop a comprehensive model giving the conditions for synchronization, and predict that it can be achieved with a total energy cost lower than 10−13 J. Our results open the path to ultra-low power computation based on the controlled synchronization of oscillators.

Superparamagnetic tunnel junctions present a number of advantages for computation. First, they can be downscaled to atomic dimensions1. Secondly, because the energy barrier separating the two magnetic configurations is small, low current densities can lead to significant action of spin torques on magnetization switching2. But how can they be harnessed for applications? A first option is to use superparamagnetic tunnel junctions as sensors. Indeed, thanks to their high sensitivity to electrical currents they are able to detect weak oscillating signals3,4,5 through the effect of stochastic resonance6. A second option is to use them as building blocks of computing systems leveraging the synchronization of oscillators for processing7,8. It has been recently recognized that coupled nano-oscillators are promising brain-inspired systems for performing cognitive tasks such as pattern recognition9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. Like neurons in some parts of the brain, they compute by synchronizing and desynchronizing depending on sensory inputs17. However, such systems require a high number of oscillators, that each need to be powered. Using superparamagnetic tunnel junctions would allow orders of magnitude gain in power consumption. In addition, by shrinking their dimensions they can be fabricated from the same magnetic stack as stable junctions, allowing for densely interweaving oscillations and memory.

Nevertheless there are a number of prerequisites to be able to use superparamagnetic tunnel junctions for computational purposes. In particular, it is necessary to identify handles providing control over their synchronization and to model accurately the associated physics for simulating large scale systems of interacting oscillators. Here we show experimentally that we can induce the phase-locking of a superparamagnetic tunnel junction to a weak periodic signal through the addition of a small electrical noise, and that we can suppress the phase-locking by adding more noise. While the stochastic behavior of most systems becomes unpredictable when shrunk to nanometer scale, the dedicated model we develop here encompasses all our experimental results. The quantitative agreement between model and experiments allows predicting the power consumption of computing systems harnessing phase-locking of superparamagnetic tunnel junctions.

Experimental Results

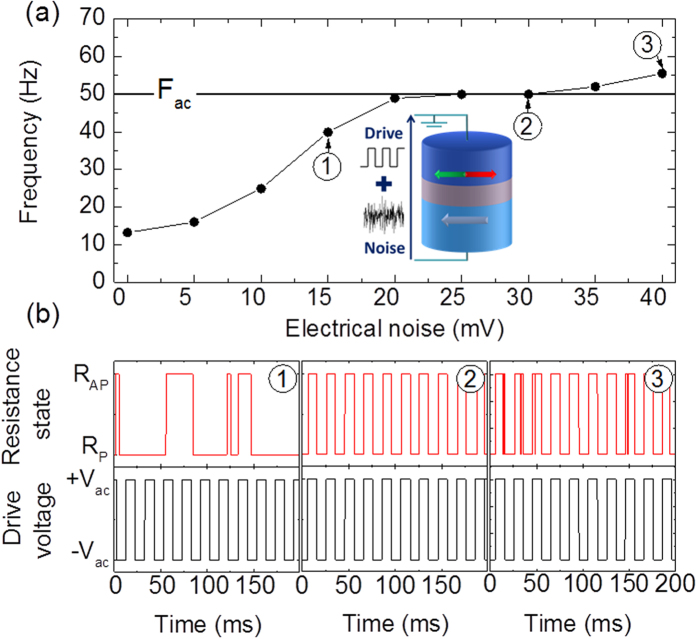

We study experimentally superparamagnetic tunnel junctions with an MgO barrier and a CoFeB free layer of dimensions 60 × 120 × 1.7 nm3 (details in Methods). As depicted in the inset of Fig. 1a, we evaluate their ability to phase lock to a weak square periodic drive voltage in the presence of electrical white noise, at room temperature. We set the drive frequency at Fac = 50 Hz and the drive amplitude at Vac = 63 mV, which corresponds to approximately 25% of the voltage threshold for deterministic magnetization switching at 0 K. Figure 1a shows how the mean frequency of the stochastic oscillator evolves when the amplitude of the electrical noise is increased.

Figure 1. Controlling the phase locking of a superparamagnetic tunnel junction through electrical noise: experimental results.

A square periodic voltage of amplitude Vac = 63 mV and frequency Fac = 50 Hz as well as white Gaussian electrical noise are applied to the junction. (a) Inset: schematic of the superparamagnetic tunnel junction driven by a periodic square voltage and electrical noise. Main: junction’s mean frequency as a function of electrical noise amplitude (standard deviation σNoise). (b) Times traces of the junction’s resistance (top) and applied voltage (bottom) for three different levels of noise with standard deviations: (1) σNoise = 15 mV, (2) σNoise = 30 mV and (3) σNoise = 40 mV.

We observe three different regimes, illustrated in Fig. 1b. As can be seen in the first panel, the jumps in the junction resistance, corresponding to reversals of the magnetization, remain stochastic for small values of injected electrical noise. In addition, the junction mean frequency is lower than the drive frequency. Usually, adding noise to a system tends to destroy its coherence and is detrimental to the occurrence of a synchronized regime. On the contrary, in our case, by increasing the electrical noise amplitude, we can increase the junction’s mean frequency towards the drive frequency. Eventually, for an optimal range of electrical noise (between 20 and 30 mV), we observe both frequency locking (as evidenced from the plateau in Fig. 1a), and phase locking to the driving signal (as shown in panel 2). In this second regime, electrical noise optimally assists the periodic drive to overcome the voltage threshold for magnetization switching at every oscillation of the drive voltage18,19,20. In the third regime (panel 3), higher amplitude electrical noise induces unwanted switches of the magnetization and prevents synchronization.

Analytical model and simulations of phase-locking

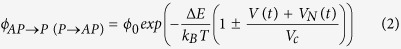

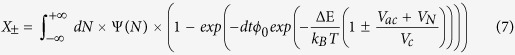

Phase-locking to an external drive controlled by electrical noise has been experimentally demonstrated in a few non-linear systems such as Schmitt triggers19,21 or lasers22 but never in a nanoscale system as achieved here. In order to assess the potential of superparamagnetic tunnel nanojunctions for applications, we now propose a model that accurately describes their noise-mediated synchronization to weak periodic signals. The thermally activated escape rate of a single domain magnetization, modulated by spin transfer torque23,24, has a simple expression25,26,27:

|

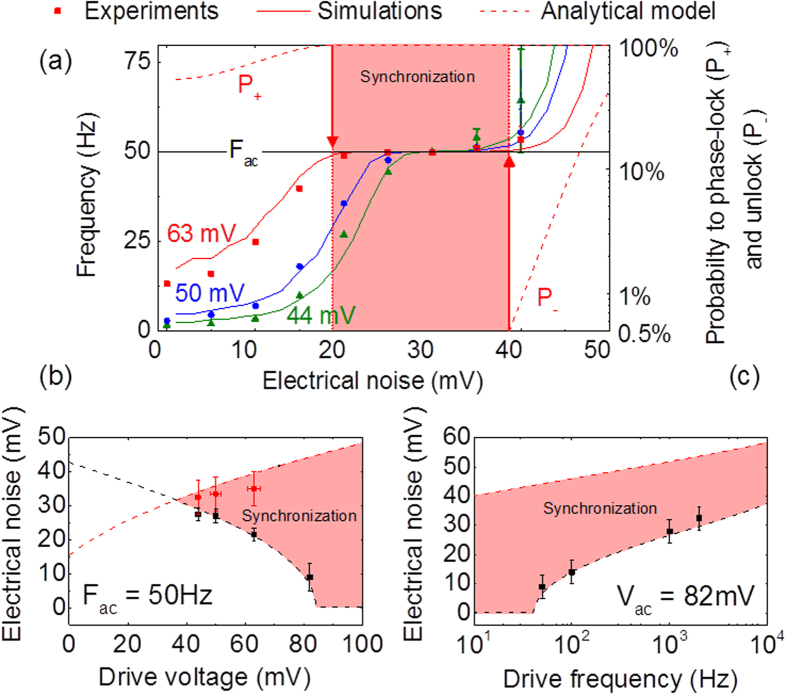

where ϕ0 is the attempt frequency, ΔE the energy barrier between the two stable states, T the temperature and Vc the voltage threshold for deterministic switching26,27. In our case the driving force is the sum of the periodic voltage V(t) = ±Vac and the electrical noise VN(t), which is assumed Gaussian with standard deviation σNoise. In consequence there are two sources of noise in our system: electrical and thermal noises (T = 300 K). Using Eq. (1), we can numerically compute the junction’s mean frequency as a function of the electrical noise amplitude28 (see Methods). Figure 2a compares the experimental data (symbols) measured for different amplitudes of the periodic drive to the results of numerical simulations (solid lines). All simulations have been performed using a single set of fitting parameters (Vc = 235 mV and ΔE/kBT = 22.5), emphasizing the remarkable agreement with experimental results.

Figure 2. Modelling the phase locking of superparamagnetic tunnel junctions to an external periodic drive in the presence of electrical noise.

Simulations and analytical calculations are done with the same set of parameters: Vc = 235 mV and ΔE/kBT = 22.5. (a) A square periodic voltage of frequency Fac = 50 Hz and a white Gaussian electrical noise are applied to a magnetic tunnel junction. Three amplitudes are studied: Vac = 44 mV (green), Vac = 50 mV (blue) and Vac = 63 mV (red). Left axis: frequency of the oscillator versus the standard deviation of the noise, both experimental results (circles, squares and triangles) and numerical results (solid lines) are represented. Right axis: analytical values of probabilities P+ and P− to switch during half a period Tac/2 versus noise (dash lines). Vertical dot lines represent the noise levels for which P+ = 99.5% and P− = 0.5% for a 63 mV amplitude. The horizontal black solid line represents the drive frequency Fac. (b,c) Lower noise bound (black) and higher noise bound (red) of the synchronization plateau versus the drive voltage (b) and versus the drive frequency (c). Both analytical values (dash lines) and experimental results (circles and squares) are presented. In the red zones the oscillator is synchronized with the excitation.

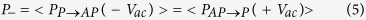

The analytical models that have been developed in the past to describe noise-induced phase locking18,20,29 focused on cases for which noise can be taken into account as a time-independent variable in the escape rates, such as temperature in Eq. (1). However in our case, the escape rates from the parallel and antiparallel states are time varying, random variables because they depend on the electrical noise VN(t). In order to go further, we develop an original and generic method to analytically determine the conditions for synchronization. Starting from Eq. (1), we calculate the probabilities P+ (P−) for the magnetization to switch from out-of-phase with the drive voltage to in-phase (from in-phase to out-of-phase) during half a period. The details of the derivation and the expressions for the phase-locking and phase-unlocking probabilities P+ and P− are given in Methods. In the vicinity of the plateau, the mean frequency of the junction is described by F = Fac(2P+ + 2P− − 1). Considering a 99% frequency locking requirement, the boundaries of the synchronization region are given by P+ >99.5% and P− <0.5%, as shown by the red arrows in Fig. 2a for the case of a drive amplitude of 63 mV. Figure 2b,c show that our analytical model (dotted lines) quantitatively predicts the boundaries of the experimental synchronization zone (symbols) over the whole range of investigated parameters. As can be seen in Fig. 2b, the range of electrical noise for which phase-locking occurs increases with the drive amplitude. When the drive amplitude is too low (here below 37 mV), synchronization cannot be achieved. On the other hand, at large drive amplitudes (here above 85 mV), phase locking can be achieved through room temperature thermal noise alone, without the need to add up electrical noise. In addition, as shown in Fig. 2c, phase-locking is achievable for frequencies orders of magnitude higher than the natural mean frequency (0.1 Hz here). The fact that synchronization occurs for broad ranges of noise amplitude provides robustness to variability of the device. For instance, if a drive voltage Vac = 63 mV with frequency Fac = 50 Hz is applied to the junction, a 5% variability of its area would shrink the synchronization noise range from 21 mV to 16 mV. This leaves a significant synchronization plateau that can be exploited for applications. Nevertheless, this variability increases the minimal drive amplitude required to achieve synchronization from Vac = 31 mV to Vac = 39 mV.

Estimation of the energy needed to synchronize superparamagnetic tunnel junctions

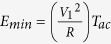

Having validated our analytical model, we can now predict the energy consumption of spintronic circuits leveraging the synchronization of superparamagnetic tunnel junctions for computing. In such circuits, a calculation is finished once steady synchronization patterns are formed within the assembly of oscillators after its perturbation by an external input signal15,16. Superparamagnetic tunnel junctions can phase lock fast, typically in a single period of the input signal30. To evaluate the energy needed for such operation, we focus on the most recent generation of magnetic tunnel junctions with perpendicularly magnetized layers. We consider junctions small enough (<30 nm) for their free layer to behave as a macrospin2 and to be described by Eq. (1). Using parameters (energy barrier, critical voltage and resistance) determined from experiments by Sato et al.2, we calculate the minimum energy Emin necessary to synchronize the junction with and without the help of electrical noise.

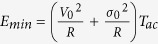

Figure 3 shows the evolution of Emin as a function of junction diameter for different drive frequencies. When only thermal noise is used,  where V1 is the minimum drive voltage required to phase-lock the junction in one drive period Tac (see inset in Fig. 3 and Methods). When electrical noise is added, the minimum energy becomes

where V1 is the minimum drive voltage required to phase-lock the junction in one drive period Tac (see inset in Fig. 3 and Methods). When electrical noise is added, the minimum energy becomes  , where V0 is the minimum drive voltage required for phase-locking and σ0 the corresponding noise level (see inset in Fig. 3 and Methods). Interestingly, for each drive frequency, there is an optimal diameter Dmin for which the energy needed to achieve phase-locking is minimal. Indeed the junction diameter determines its natural frequency: large diameters correspond to low frequencies because large magnetic volumes are more difficult to switch. Above Dmin, the drive frequency is larger than the junction’s mean frequency. To phase-lock, the junction has to be accelerated. In the absence of electrical noise, this can be done through an increase of the drive amplitude, which enhances the ability of the junction to synchronize (stars in Fig. 3).

, where V0 is the minimum drive voltage required for phase-locking and σ0 the corresponding noise level (see inset in Fig. 3 and Methods). Interestingly, for each drive frequency, there is an optimal diameter Dmin for which the energy needed to achieve phase-locking is minimal. Indeed the junction diameter determines its natural frequency: large diameters correspond to low frequencies because large magnetic volumes are more difficult to switch. Above Dmin, the drive frequency is larger than the junction’s mean frequency. To phase-lock, the junction has to be accelerated. In the absence of electrical noise, this can be done through an increase of the drive amplitude, which enhances the ability of the junction to synchronize (stars in Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Energy required to phase-lock a perpendicularly magnetized superparamagnetic tunnel junction: predictions of the analytical model.

Upper inset: schematic of Fig. 2b. The circle indicates the lowest drive voltage V0 for which synchronization can be achieved and the corresponding electrical noise level σ0. The star indicates the lowest drive voltage V1 for which synchronization can be achieved through thermal noise alone without addition of any electrical noise. Lower inset: schematic view of a perpendicularly magnetized tunnel junction. Main: Calculated minimum energy required to synchronize a perpendicularly magnetized superparamagnetic tunnel junction to a periodic voltage drive in one period, plotted versus the diameter of the junction, for different drive frequencies. Circles represent the case where electrical noise has been added while stars represent the case where only thermal noise is used.

Adding electrical noise lowers the drive amplitude required to synchronize and thus decreases the total amount of energy to provide (circles in Fig. 3). Below Dmin, the junction has to be slowed down in order to phase lock. As electrical noise always speeds up the oscillator by increasing the number of switches, this can only be achieved by increasing the drive amplitude. Our results indicate that carefully engineering the junctions’ dimensions can drastically decrease the energy required to achieve phase-locking, about 8 × 10−14 J for a drive frequency of 10 MHz (Fig. 3). By comparison, synchronizing a harmonic dc-driven spin-torque oscillator with a 10 GHz frequency31 to a drive current would require 100 times more energy (see Methods). CMOS implementations of oscillators for bio-inspired computing applications are also more costly in terms of energy, with a consumption above 7 × 10−12 J for integrate and fire neurons32. In addition they occupy a large area on chip, typically several hundreds of μm2.

Because of these issues of size and energy consumptions, bio-inspired computing systems leveraging the synchronization of coupled oscillators for computing have never been implemented in CMOS. Thanks to their small area and low energy consumption, arrays of phase-locked superparamagnetic tunnel junctions are a promising alternative for pattern recognition. We take the example of image classification, which generally requires one oscillator per pixel15,16 to evaluate the energy consumption of magnetic processor leveraging the synchronization of superparamagnetic tunnel junctions. Using the figures determined above, we predict that a superparamagnetic spintronic circuit can classify 1Mpixel images while consuming less than 0.1 μJ. A challenge for designing such computing circuits will be the generation and control of both the drive signal and the electrical noise. Towards this goal, only two levels of noise are sufficient to induce synchronized or non-synchronized states. One possible low power path would be to use the electrical noise naturally present in the circuits, such as, for instance, the noise generated by assemblies of stochastic devices. Our study thus opens the path to ultra-low power stochastic computation harnessing superparamagnetism.

Methods

Sample

The samples are in-plane magnetized magnetic tunnel junctions. They were fabricated by sputtering, with the stack: substrate (SiO2)/Buffer layer 35 nm/IrMn 7 nm/CoFe 2.5 nm/Ru 0.85 nm/CoFeB 2.4 nm/MgO-barrier 1.0 nm/CoFeB 1.7 nm/capping layer 14 nm. The whole stack was annealed before microfabrication at 300 °C under a magnetic field of 1 Tesla for 1 hour. Patterning was then performed by e-beam lithography, resulting in nanopillars with elliptic 60 × 120 nm2 cross-sections.

Experiments

The electrical noise applied to the junction is white Gaussian noise with a bandwidth FN = 40MHz. Measurements are performed under an in-plane applied field H0 of 59 Oe in order to compensate the residual stray field produced by the reference layer (synthetic antiferromagnet), and thus equilibrate dwell times in the P and AP states in the absence of applied voltage.

Data analysis

In order to determine the resistance of the junction as a function of time, we record the current flowing through the junction with an oscilloscope. As the driven voltage oscillates between two values (+Vac and −Vac) and the magnetic tunnel junction switches between two resistance states (RAP = 640 Ω and RP = 390 Ω), the current flowing through the junction can take four values. At high level of electrical noise, the determination of the resistance state of the junction becomes more difficult, as can be seen from the increasing width of error bars in Fig. 2a.

Numerical simulations

We assume that the free layer of the superparamagnetic tunnel junction can be considered as a single domain magnetization element and follows the Neel-Brown model25 in which the escape rates of this process are described by Arrhenius equations and can be controlled through the handle of spin transfer torque26,27

|

In this study ϕ0 = 109 s−1 is the effective attempt frequency27, ΔE is the energy barrier between the two stable states, kB is the Boltzmann constant, T is the temperature, U(t) = V(t) + VN(t) is the applied voltage and Vc is the threshold voltage for deterministic switching26,27.

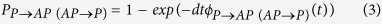

For numerical simulations we compute at each time step the probability for the magnetization to switch during the time interval dt knowing the initial state:

|

A pseudo-random number is then generated to decide whether the switch occurs or not. The parameters of the model: Fac, Vac (frequency and amplitude of the driving square voltage) and FN (bandwidth of the electrical Gaussian noise) have values identical to the experimental protocol. The chosen time step corresponds to the smallest time scale of the experimental noise generator dt = 1/FN. The mean frequency is computed as the mean number of oscillations of the junction per second.

Matching numerical predictions with experimental results for the evolution of the frequency of the magnetic tunnel junction versus the level of noise (Fig. 2(a) left axis) allows us to extract the two free parameters of the model: the ratio ΔE/T = 22.5 and the critical voltage Vc = 235 mV.

Analytical model

The specificity of external noise is that it introduces a supplementary level of randomness as compared to the internal noise provided by temperature: the escape rates depend on the electrical noise N(t) and are therefore random variables themselves. Therefore, the probability for the magnetization to switch during half a period Tac/2 of the drive can only defined as an average over the possible values of N:

|

|

where  is the probability to switch from P to AP during Tac/2 when the excitation voltage is +Vac.

is the probability to switch from P to AP during Tac/2 when the excitation voltage is +Vac.

Therefore, P+ is the probability to switch from out of phase to in-phase during Tac/2 while P− is the probability to switch from in-phase to out of phase during Tac/2.

|

with

|

and Ψ(N) is a Gaussian distribution over N.

When the level of noise is sub-optimal, synchronization is limited by the junction’s ability to phase-lock fast enough when the excitation voltage reverses. Therefore the mean frequency of the junction is F = Fac(2P+ − 1). On the other hand, when the noise level is supra-optimal, synchronization is limited by the junction’s tendency to jump out of phase with the excitation voltage. Therefore F = Fac(1 + 2P−). On the whole, near the plateau, the mean frequency of the junction is F = Fac(2P+ + 2P− − 1). In consequence, P+ > 99.5% and P− < 0.5% means that the junction is frequency-locked with less than 1% error.

V0 is computed as the minimum voltage drive Vac for which there is an electrical noise level σ0 that satisfies P+ > 99.5% and P < 0.5%. V1 is the minimum voltage drive Vac for which P+ > 99.5% and P− < 0.5% is satisfied at zero electrical noise.

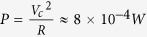

Energy consumption predictions

We consider a perpendicularly magnetized tunnel junction and make the assumption that the free layer is a single magnetization element (D < 30 nm). The thickness of the free layer in the junction is fixed, so that the energy barrier between the two magnetization states scales with the square of the diameter D:  . We also consider that the resistance × area product RA of the junction is constant, so that the resistance of the junction can be written as:

. We also consider that the resistance × area product RA of the junction is constant, so that the resistance of the junction can be written as:  . We use numerical parameters from Sato et al.2: ΔE0 = 90 kBT, D0 = 30 nm, Vc = 0.71 V and RA = 10 Ω.μm2.

. We use numerical parameters from Sato et al.2: ΔE0 = 90 kBT, D0 = 30 nm, Vc = 0.71 V and RA = 10 Ω.μm2.

For the energy consumption of a deterministic spin-torque oscillator we considered the same model with a resistance × area product RA = 3 Ω.μm2 and a diameter of 24 nm (which corresponds to the traditionally required energy barrier of ΔE = 60 kBT). The power consumption is dominated by the DC current required to induce high frequency oscillations of the magnetization, therefore  . Thus for a spin torque oscillator of 10 GHz frequency taking Tsync = 10 ns to reach synchronization31 the energy consumption is E = P × Tsync ≈ 8 × 10−12 J.

. Thus for a spin torque oscillator of 10 GHz frequency taking Tsync = 10 ns to reach synchronization31 the energy consumption is E = P × Tsync ≈ 8 × 10−12 J.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Mizrahi, A. et al. Controlling the phase locking of stochastic magnetic bits for ultra-low power computation. Sci. Rep. 6, 30535; doi: 10.1038/srep30535 (2016).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support from the FET-OPEN Bambi project No. 618024 and the ANR MEMOS n° ANR-14-CE26-0021. A.M. acknowledges financial support from the Ile-de-France regional government through the DIM nano-K program. R.L. acknowledges financial support from the ANR agency (SPINNOVA ANR-11-NANO-0016). N.L. acknowledges financial support from a public grant overseen by the French National Research Agency (ANR) as part of the “Investissements d’Avenir” program (Labex NanoSaclay, reference: ANR-10-LABX-0035).

Footnotes

Author Contributions A.F., H.K. and S.Y. designed, optimized, and fabricated the superparamagnetic tunnel junctions. A.M. and R.L. conducted the experiments. A.M., N.L., D.Q. and J.G. developed the theoretical model and wrote this letter. All authors discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Khajetoorians A. A. et al. Current-Driven Spin Dynamics of Artificially Constructed Quantum Magnets. Science 339, 55–59 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato H. et al. Properties of magnetic tunnel junctions with a MgO/CoFeB/Ta/CoFeB/MgO recording structure down to junction diameter of 11 nm. Applied Physics Letters 105, 062403 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Finocchio G., Krivorotov I. N., Cheng X., Torres L. & Azzerboni B. Micromagnetic understanding of stochastic resonance driven by spin-transfer-torque. Phys. Rev. B 83, 134402 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- d’Aquino M., Serpico C., Bonin R., Bertotti G. & Mayergoyz I. D. Stochastic resonance in noise-induced transitions between self-oscillations and equilibria in spin-valve nanomagnets. Phys. Rev. B 84, 214415 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X., Boone C., Zhu J. & Krivorotov I. Nonadiabatic Stochastic Ressonancee of a nanomagnet excited by spin torque. Phys. Rev. Lett. (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammaitoni L., Hänggi P., Jung P. & Marchesoni F. Stochastic resonance. Rev. Mod. Phys. 70, 223–287 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Locatelli N., Cros V. & Grollier J. Spin-torque building blocks. Nat Mater. 13, 11–20 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locatelli N. et al. Noise-Enhanced Synchronization of Stochastic Magnetic Oscillators. Phys. Rev. Applied 2, 034009 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Pufall M. et al. Physical implementation of coherently-coupled oscillator networks. IEEE Journal on Exploratory Solid-State Computational Devices and Circuits PP, 1–1 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Chen A., Hutchby J., Zhirnov V. & Bourianoff G. Emerging Nanoelectronic Devices. (John Wiley & Sons, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Yogendra K., Fan D. & Roy K. Coupled Spin Torque Nano Oscillators for Low Power Neural Computation. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 51, 1–9 (2015).26203196 [Google Scholar]

- Locatelli N. et al. Spin torque nanodevices for bio-inspired computing. In 2014 14th International Workshop on Cellular Nanoscale Networks and their Applications (CNNA) 1–2, doi: 10.1109/CNNA.2014.6888659 (2014). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A. A., Bain J. A. & Weldon J. A. Phase Coupling and Control of Oxide-Based Oscillators for Neuromorphic Computing. IEEE Journal on Exploratory Solid-State Computational Devices and Circuits 1, 58–66 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Corinto F., Ascoli A. & Gilli M. Nonlinear Dynamics of Memristor Oscillators. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I: Regular Papers 58, 1323–1336 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Aonishi T. Phase transitions of an oscillator neural network with a standard Hebb learning rule. Phys. Rev. E 58, 4865–4871 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Hoppensteadt F. C. & Izhikevich E. M. Oscillatory Neurocomputers with Dynamic Connectivity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 2983–2986 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Fell J. & Axmacher N. The role of phase synchronization in memory processes. Nat Rev Neurosci. 12, 105–118 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neiman A., Schimansky-Geier L., Moss F., Shulgin B. & Collins J. J. Synchronization of noisy systems by stochastic signals. Phys. Rev. E 60, 284–292 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulgin B., Neiman A. & Anishchenko V. Mean Switching Frequency Locking in Stochastic Bistable Systems Driven by a Periodic Force. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 4157–4160 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund J. A., Schimansky-Geier L. & Hänggi P. Frequency and phase synchronization in stochastic systems. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science 13, 225–238 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khovanov I. A. & McClintock P. V. E. Synchronization of stochastic bistable systems by biperiodic signals. Phys. Rev. E 76, 031122 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbay S., Giacomelli G., Lepri S. & Zavatta A. Experimental study of noise-induced phase synchronization in vertical-cavity lasers. Phys. Rev. E 68, 020101 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger L. Emission of spin waves by a magnetic multilayer traversed by a current. Phys. Rev. B 54, 9353–9358 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slonczewski J. C. Excitation of spin waves by an electric current. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 195, L261–L268 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Brown W. F. Thermal Fluctuations of a Single-Domain Particle. Phys. Rev. 130, 1677–1686 (1963). [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. & Zhang S. Thermally assisted magnetization reversal in the presence of a spin-transfer torque. Phys. Rev. B 69, 134416 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Rippard W., Heindl R., Pufall M., Russek S. & Kos A. Thermal relaxation rates of magnetic nanoparticles in the presence of magnetic fields and spin-transfer effects. Phys. Rev. B 84, 064439 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Mizrahi A. et al. Magnetic Stochastic Oscillators: Noise-Induced Synchronization to Underthreshold Excitation and Comprehensive Compact Model. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 51, 1–4 (2015).26203196 [Google Scholar]

- Casado-Pascual J. et al. Theory of frequency and phase synchronization in a rocked bistable stochastic system. Phys. Rev. E 71, 011101 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pikovsky A., Rosenblum M. & Kurths J. Synchronization: a universal concept in nonlinear sciences. 12, (Cambridge university press, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- Rippard W., Pufall M. & Kos A. Time required to injection-lock spin torque nanoscale oscillators. Applied Physics Letters 103, 182403 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Livi P. & Indiveri G. A current-mode conductance-based silicon neuron for address-event neuromorphic systems. In IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems, 2009. ISCAS 2009 2898–2901, doi: 10.1109/ISCAS.2009.5118408 (2009). [DOI] [Google Scholar]