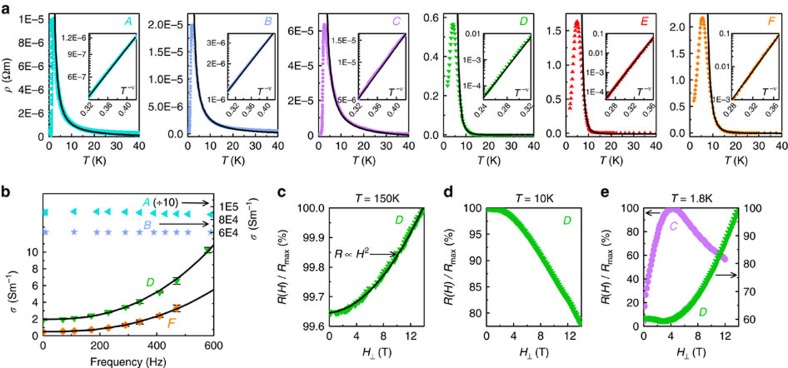

Figure 3. Influence of electron localization on the low-temperature electrical transport.

(a) Low-temperature divergence in the electrical resistivity ρ(T) for six Na2−δMo6Se6 crystals A–F. Black lines are least-squares fits using a variable range hopping (VRH) model (Supplementary Note III). T0 (and hence the disorder) rises monotonically from crystal A→F. Insets: ρ(T−v) plotted on a semi-logarithmic scale; straight lines indicate VRH behaviour. (b) Frequency-dependent conductivity σ(ω) in crystals A, B, D and F (data points). Error bars correspond to the s.d. in the measured conductivity, that is, our experimental noise level. For the highly-disordered crystals D and F, the black lines illustrate the  trend predicted30 for strongly-localized electrons (using d=1). Data are acquired above Tpk, at T=4.9, 4.9, 4.6, 6 K for crystals A, B, D and F, respectively. (c–e) Normalized perpendicular magnetoresistance (MR) in crystal D (see Methods for details of the magnetic field orientation). At 150 K (c), the effects of disorder are weak and ρ∝H2 due to the open Fermi surface. In the VRH regime at 10 K (d), magnetic fields delocalize electrons due to a Zeeman-induced change in the level occupancy34, leading to a large negative MR. For T<Tpk (e), the high-field MR is positive as superconductivity is gradually suppressed. The weak negative MR below H=3 T may be a signature of enhanced quasiparticle tunnelling: in a spatially-inhomogeneous superconductor, magnetic field-induced pair-breaking in regions where the superconducting order parameter is weak can increase the quasiparticle density and hence reduce the electrical resistance. MR data from crystal C are shown for comparison: here the disorder is lower and H∼4 T destroys superconductivity.

trend predicted30 for strongly-localized electrons (using d=1). Data are acquired above Tpk, at T=4.9, 4.9, 4.6, 6 K for crystals A, B, D and F, respectively. (c–e) Normalized perpendicular magnetoresistance (MR) in crystal D (see Methods for details of the magnetic field orientation). At 150 K (c), the effects of disorder are weak and ρ∝H2 due to the open Fermi surface. In the VRH regime at 10 K (d), magnetic fields delocalize electrons due to a Zeeman-induced change in the level occupancy34, leading to a large negative MR. For T<Tpk (e), the high-field MR is positive as superconductivity is gradually suppressed. The weak negative MR below H=3 T may be a signature of enhanced quasiparticle tunnelling: in a spatially-inhomogeneous superconductor, magnetic field-induced pair-breaking in regions where the superconducting order parameter is weak can increase the quasiparticle density and hence reduce the electrical resistance. MR data from crystal C are shown for comparison: here the disorder is lower and H∼4 T destroys superconductivity.