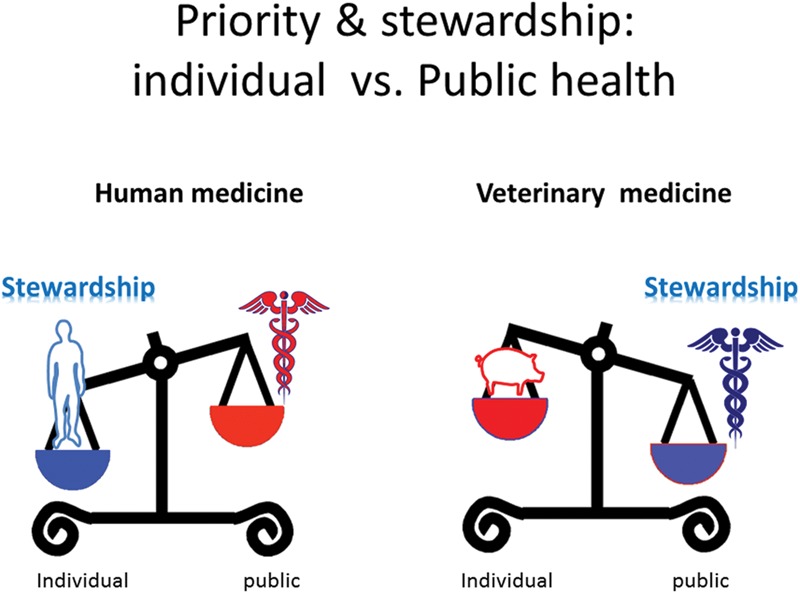

FIGURE 3.

Priority and stewardship for human and veterinary medicine and the paradigm of prudent use of AMDs. The paradigm of prudent use of AMDs in animals can be insufficient and even counter-productive. This is because such recommendations fail to recognize that the main sources of the resistance determinants, which are amplified by veterinary AMD usage, are derived not from the pathogenic microbiota but from the commensal GIT microbiota. An appropriate stewardship regarding the target pathogen (the priority for human medicine) can actually increase the public health issues when directly extrapolated to veterinary medicine. For example, one recommendation, for the prudent use of AMDs in human and animal medicine, fully justified from both animal and human health perspectives, is the possible increase of dosage regimens for older drugs to comply with current PK/PD concepts. However, this may be detrimental from the perspective public health. A second example of a questionable recommendation is the compulsory recourse to Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing for AMDs classified as critical for human use, when, in most instances, there are no specific corresponding veterinary breakpoints. Another issue is the marketing of inexpensive generic products in veterinary medicine. Although these have important uses in disease control, there is the possibility that they might be used clinically when (more costly) hygienic, husbandry and disease containment options would be more appropriate [for details see (Toutain and Bousquet-Melou, 2013)]. An a priori sound recommendation is to give preference to local rather than systemic AMD administration, as in the treatment of clinical mastitis or at drying off in dairy cattle. In fact this may be counterproductive as it does not allow for the fact that the waste and unsaleable milk (containing a higher residual amount of AMD than that associated with systemic treatment), is commonly used to feed calves and may be responsible for the emergence of resistance in their GIT microbiota (Brunton et al., 2012; Duse et al., 2013).