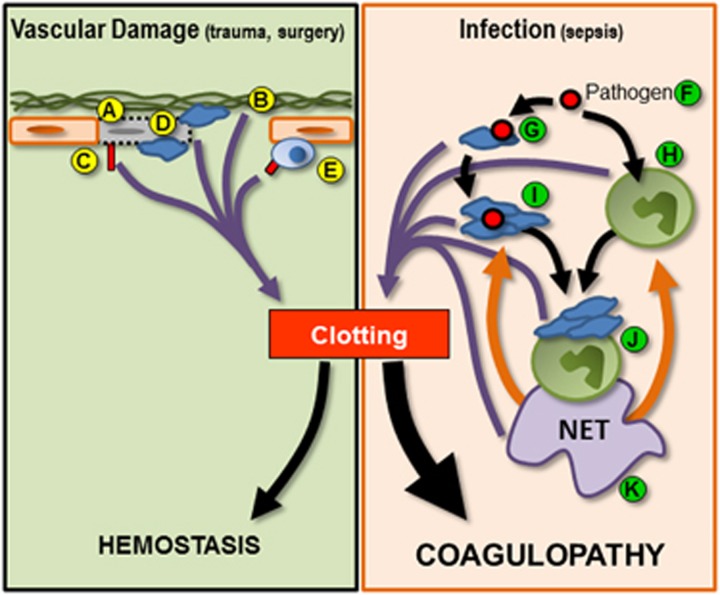

Figure 2.

Schematic illustrating mechanisms of initiation of hemostatic coagulation and infection-induced coagulopathy. Normal hemostasis (green box, left half of figure) can be initiated by (A) endothelial stress and damage. Endothelial death can result in the exposure of the subendothelial extracellular matrix (B), which can also initiate coagulation. Tissue factor expression by endothelial cells (C) and platelet recruitment to sites of damage (D) serve to activate/amplify coagulation. In addition, recruitment and activation of leukocytes such as monocytes can result in increased tissue factor expression (E), further driving coagulation. During infection (orange box, right half of figure), pathogens (F) serve to activate both platelets (G) and leukocytes such as neutrophils (H). Activated platelets can form circulating aggregates (I) or bind to the surface of neutrophils (J) inducing the release of NETs (K). Activated platelets, leukocytes, platelet–leukocyte aggregates and NETs feed into the clotting cascade (purple arrows), resulting in the inappropriate and uncontrolled systemic coagulation. In addition, NETs mediated a positive feedback loop within inflammation (orange arrows) further driving platelet and neutrophil activation and inducing the production of additional NETs. This uncontrolled amplification of clotting tips the balance away from hemostasis and toward systemic coagulopathy.