Abstract

Electrospray ionization (ESI) on mixtures of acidic fibrinopeptide B and two peptide analogs with trivalent lanthanide salts generates [M + Met + H]4+, [M + Met]3+, and [M + Met − H]2+, where M = peptide and Met = metal (except radioactive promethium). These ions undergo extensive and highly efficient electron transfer dissociation (ETD) to form metallated and non-metallated c- and z-ions. All metal adducted product ions contain at least two acidic sites, which suggests attachment of the lanthanide cation at the side chains of one or more acidic residues. The three peptides undergo similar fragmentation. ETD on [M + Met + H]4+ leads to cleavage at every residue; the presence of both a metal ion and an extra proton is very effective in promoting sequence-informative fragmentation. Backbone dissociation of [M + Met]3+ is also extensive, although cleavage does not always occur between adjacent glutamic acid residues. For [M + Met − H]2+, a more limited range of product ions form. All lanthanide metal peptide complexes display similar fragmentation except for europium (Eu). ETD on [M + Eu − H]2+ and [M + Eu]3+ yields a limited amount of peptide backbone cleavage; however, [M + Eu + H]4+ dissociates extensively with cleavage at every residue. With the exception of the results for Eu(III), metallated-peptide ion formation by ESI, ETD fragmentation efficiencies, and product ion formation are unaffected by the identity of the lanthanide cation. Adduction with trivalent lanthanide metal ions is a promising tool for sequence analysis of acidic peptides by ETD.

Keywords: Electron transfer dissociation, lanthanide metal adduction, acidic peptides, sequence-informative fragmentation, trivalent lanthanide cations

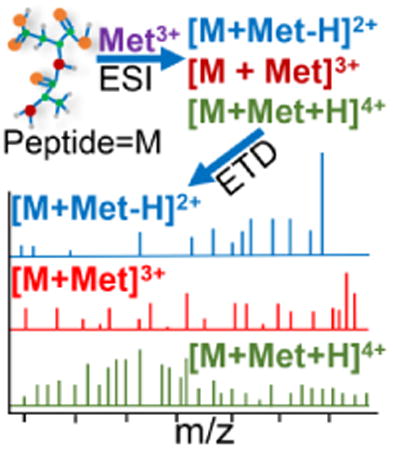

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Many naturally occurring acidic peptides and proteins are involved in biological processes. For example, fibrinopeptide B is part of the blood coagulation process [1], gastrin I is utilized in digestion in the stomach [2, 3], N-arginine dibasic convertase is important to neurological functions [4], and low-molecular-weight chromium binding peptide (LMWCr) is involved in carbohydrate metabolism [5-7]. These peptides often contain a series of adjacent acidic residues and, consequently, may be difficult to protonate. Some highly acidic peptides will not form doubly or even singly protonated ions by electrospray ionization (ESI) or matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) [8-11].

The tendency of acidic peptides to deprotonate can cause problems for tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) analysis in the positive ion mode by electron transfer dissociation (ETD) and electron capture dissociation (ECD). In ETD and ECD, addition of an electron to a multiply charged ion creates a charge reduced radical species that undergoes non-ergodic processes; the result is N-Cα cleavage along the peptide backbone to produce c- and z-ions [12-18]. Electron-based techniques usually lead to more uniform cleavage along the peptide backbone [12, 13, 19-21] than collisionally activated dissociation methods (CAD/CID), and labile post-translational modification sites such as phosphorylation are generally conserved [22-27]. A drawback of both ECD and ETD is that a multiply charged precursor ion is necessary [12, 17, 19, 28-30] because addition of an electron to a singly charged ion generates a neutral molecule that cannot be detected by mass spectrometry [31]. Also, multiple charging is advantageous because fragmentation by MS/MS generally increases with higher charge states on the precursor ion [13, 32-38].

Studies using a variety of metal ions have demonstrated the ability of metallated peptides to provide sequence-informative fragmentation by ECD. Lui and Håkansson [39] complexed divalent and alkaline earth metals with the neuropeptide substance P to produce [M + Met + H]3+, where M = peptide and Met = metal. The ECD spectra were dominated by a-, b-, c-, y-, and z-ions, and the identity of the metal ion affected fragmentation. In another study by these same researchers [40], extensive sequence coverage resulted from ECD of metallated ions produced by mixing divalent alkaline earth metal salts with peptides containing O-sulfated tyrosine residues; these spectra were dominated by c- and z-ions. Members of the c- and z-series were also found when Chan and coworkers [41] performed ECD on complexes of divalent alkaline earth metal ions with two nonapeptides. A wider variety of backbone cleavage ions, a-, b-, c-, y- and z-, were seen when Chan and coworkers [42-44] performed ECD on several small peptides adducted to divalent transition metal cations. In one study [43], these researchers observed low fragmentation efficiencies, and the metal adducted precursor ion was over 30 times greater in intensity than product ions in the ECD spectra. In an ECD study involving Cu(II)-peptide complexes by the Chan group [44], only metal adducted a-, b-, and y-ions form; the researchers determined that the type of basic residue, length of peptide sequence and the presence of amide hydrogen(s) affected the series of metallated product ions generated. More recently, Chan and coworkers [45] performed ECD on model peptides metallated with three main group metal trivalent cations and one transition metal cation. A variety of metallated and non-metallated a-, b-, c-, and z-ions were observed, and the identity of the trivalent cation affected product ion formation. Voinov et al. [46] also found a range of product ions in ECD experiments on singly and doubly sodiated substance P analogs and on an amidated phosphorylated tyrosine kinase peptide. Heeren and coworkers [47, 48] observed differences in the ECD spectra of [M + Met]2+ for a 9-residue oxytocin peptide by varying the divalent transition metal. Williams and coworkers [49] found abundant formation of c- and z-ions for ECD on metal-peptide complexes of cesium and lithium ions adducted to synthetic peptides containing alanine and lysine residues. Later work by the Williams group [50] showed that lanthanide metal adduction to a series of peptides yielded [M + Met − H]2+ and [M + Met]3+, which underwent ECD to yield almost complete sequence coverage.

A few metallated peptide studies have also involved ETD. Dong and Vachet [51] performed ETD on small copper-cationized peptides and observed c- and z-ions. For several acidic peptides, Asakawa and coworkers [52] demonstrated that metallated peptide ions with 2+ or 3+ charges produced by cationization with potassium or calcium ions underwent more sequence-informative ETD as compared to dissociation of the analogous protonated ions. In another study, Asakawa and Wada [53] complexed peptides containing cysteine residues with three divalent metal ions. The nature of the metal affected the production of c- and z-ions by ETD. To date, little is known about the type of metal ion that might be most suitable for sequencing peptides.

Lanthanide ions can be favorable for multiple charging because attachment of a single metal ion delivers a 3+ charge onto a peptide. Several studies demonstrate the ability of trivalent metal cation adduction to create quasi-molecular ions with increased charge states for small peptides in ESI [50, 54-58]. In the current work, the effects of lanthanide cationization on ETD of the model acidic peptide fibrinopeptide B and two of its analogs were studied. Trivalent metal ions were used because ideally the added 3+ charge will compensate for any deprotonation at acidic residues and leave a charge of 2+ or greater on the peptide precursor ions to be subjected to ETD. Also, trivalent metal ion adduction can result in more highly charged peptide ions (3+ and 4+) that can enhance ETD/ECD fragmentation. A goal of the current study is to determine the lanthanide metal ion most suitable for promoting acidic peptide fragmentation by ETD.

Experimental

All experiments were performed on the Bruker (Billerica, MA, USA) HCTultra PTM Discovery System high capacity quadrupole ion trap (QIT) mass spectrometer. Ions were produced by ESI on mixtures of metal salts and peptides. The needle at the ESI source was grounded and the ESI capillary was glass with platinum coating at the entrance and exit. A high voltage of -3.5 kV was placed on the capillary entrance, as well as the stainless steel endplate and capillary entrance cap. Nitrogen drying gas was heated to 260°C and flowed at 5-10 L/min. Nitrogen also served as nebulizer gas and the pressure was optimized between 5 and 10 psi. A KD Scientific (Holliston, MA, USA) syringe pump was used to infuse sample solutions with a 10:1 metal ion:peptide molar ratio mixture at a flow rate of 3 μL/min. Final peptide concentrations were 5 μM in acetonitrile:water at a 50:50 volume ratio. All spectra shown are the result of signal averaging of 200 scans.

Fluoranthene served as the reagent anion for ETD experiments and was generated in a negative chemical ionization source (nCI) employing methane reagent gas. Accumulation time for the reagent anion was 8-12 ms. The lower end mass-to-charge (m/z) cutoff was set to 120 with the anion/cation reaction times in the range of 180-250 ms. The ion charge control (ICC) value was set to 300,000-400,000 to maximize electron transfer. Immediately after the anion/cation reaction, the “smart decomposition” function was used to further dissociate any charge reduced product ions; for example, analysis of [M + Met]3+ may yield an electron transfer no dissociation (ETnoD) product [M + Met]2+ that was subjected to smart decomposition. Smart decomposition enhances ETD product ion formation by using resonant excitation (very low energy CID) to overcome attractive forces (e.g., hydrogen or noncovalent bonding) that may hold peptide fragments together following the electron transfer process.

The peptide fibrinopeptide B was purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburg, PA, USA) and American Peptide Company Inc (Vista, CA, USA). Des-Arg14-[Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B was custom synthesized by Biomatik USA (Wilmington, Delaware, USA). [Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B was purchased from Anaspec EGT (Freemont, California, USA). Lanthanide(III) metal nitrate salts were purchased from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA, USA). Ultrapure Milli-Q 18 MΩ water was produced with a Barnstead (Dubuque, IA, USA) E-pure system.

Results

Adduction of Trivalent Metal Cations to Peptides

Fibrinopeptide B (pEGVNDNEEGFFSAR) was employed to investigate the ability of trivalent lanthanide cations to promote multiple positive charging in acidic peptides that routinely favor deprotonation in ESI. Two analogs were also studied. [Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B (EGVNDNEEGFFSAR) lacks the cyclic glutamic acid residue at the N-terminus, resulting in an extra acidic site at the side chain of the N-terminal glutamic acid residue and a basic amino group at the N-terminus. In des-Arg14-[Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B (EGVNDNEEGFFSA), the highly basic C-terminal arginine residue (gas-phase basicity of arginine = 1006.6 kJ/mol [59]) is absent and the N-terminal residue is not cyclized.

Fibrinopeptide B and its analogs were combined with every trivalent lanthanide cation except promethium (Pm), atomic number 61, because of its highly radioactive nature. Mass spectra in Figure 1a and 1b show praseodymium ions, Pr(III), adducted to fibrinopeptide B and [Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B, respectively. Throughout this report, Pr(III) is used as a representative lanthanide ion because it consistently yielded high quality spectra and has one major stable isotope, thus providing straight forward spectra for interpretation. The most abundant metallated ions were [M + Met + H]4+ and [M + Met]3+. Doubly charged ions, [M + Met − H]2+ and [M + 2H]2+, formed in lower abundances for fibrinopeptide B. In a recent study of lanthanide ion-peptide complexes by Williams and coworkers [50], [M + Met − H]2+ formed for peptides of less than 1000 Da in molecular mass while [M + Met]3+ dominated for larger peptides. The [M + Met + H]4+ found here has not been reported in any ETD/ECD work to date. [Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B shows a similar pattern of metallated ion formation; removal of cyclization at the N-terminal glutamic acid residue has minimal effect on metal adduction. All lanthanide ions generated abundant multiply charged precursor ions in positive ion mode ESI with each peptide.

Figure 1.

ESI mass spectra generated from 10:1 molar ratio mixtures of Pr(III) with (a) fibrinopeptide B, (b) [Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B, and (c) des-Arg14-[Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B. The reduced signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) of Figure 1c is due to the lower purity of this peptide, which was custom synthesized. The spectra have no expansion of the intensity axis; all peaks are shown to scale.

Removal of the C-terminal arginine to form des-Arg14-[Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B caused a shift in the intensity of the metal-adducted ions. Figure 1c shows the ESI spectra of this peptide with Pr(III) and is representative of species observed with the other lanthanide cations. Most abundant is [M + Met]3+, while [M + Met + H]4+ is significantly reduced. The lack of the arginine residue limits this peptide's ability to obtain a proton for formation of [M + Met + H]4+.

ETD on [M + Met − H]2+

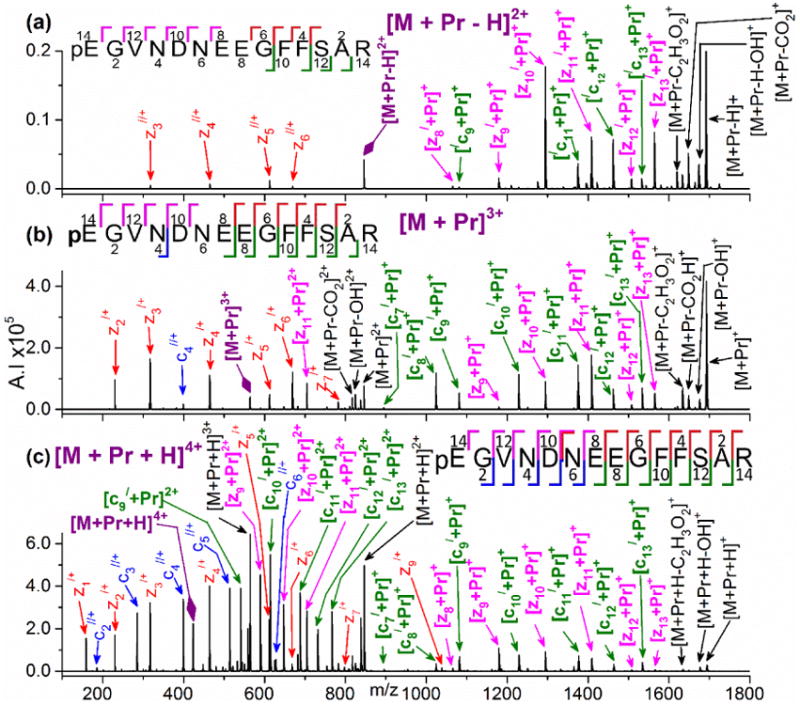

For the three peptides, the metallated ions were isolated and subjected to ETD. The established nomenclature from Roepstorff and Fohlman [60] as modified by Biemann [61] is used in labelling of spectra to keep track of the number of hydrogens incorporated into the ETD product ions. A prime symbol to the left indicates loss of a hydrogen (i.e., /cn = [cn − H]+) and to the right indicates the addition of a hydrogen at the cleavage site (i.e., cn// = [cn + 2H]+). For easier product ion identification in the figures, non-metallated z- ions are labeled in red, non-metallated c-ions in blue, metal adducted z-ions in bright pink, and metal adducted c-ions in green. Precursor ion that did not dissociate is indicated in purple with a large purple diamond arrow head. ETnoD product ions are labeled in black, as are neutral loss ions. The c- and z-ions correspond to N-Cα bond cleavage, which is the typical peptide backbone cleavage observed by ECD [13] and ETD [17].

Figure 2a shows the ETD spectrum of [M + Pr − H]2+ for fibrinopeptide B. All product ions are singly charged. The most prominent ions are of the z-series: zn//+ and [zn/ + Pr]+. Some larger metallated c-ions form and lack additional hydrogens, [/cn + Pr]+, n = 9 and 11-13, which is consistent with the precursor ion being hydrogen deficient. Cleavage occurs at every residue except for between the glutamic acid residues (E) at positions 7 and 8. Only 60-70% of the precursor ion dissociates, with a substantial amount being observed as the ETnoD product, [M + Pr − H]+, even in the presence of a smart decomposition pulse. The ETD fragmentation efficiency for [M + Met − H]2+ is lower than for the 3+ and 4+ precursor ions. The spectra contain neutral losses involving CO2, CO2H, C2H3O2, and OH. The loss of 59 Da has been observed elsewhere [62-64] and may correspond to elimination of C2H3O2 from the side chains of glutamic and aspartic acid residues. Although CH2O2 is a common side chain loss from glutamic and aspartic acid residues in electron-based techniques [65], this was not observed in the current study.

Figure 2.

ETD mass spectra of (a) [M+ Pr − H]2+, (b) [M + Pr]3+, and (c) [M + Pr + H]4+ for fibrinopeptide B produced by addition of Pr(III). Colors used to illustrate the product ions are red for non-metallated z-ions, bright pink for metallated z-ions, blue for non-metallated c-ions, green for metallated c-type ions. Product ions with neutral losses and ETnoD ions are shown in black. A large purple diamond indicates undissociated precursor ion. A prime symbol to the left indicates loss of a hydrogen (i.e., /cn = [cn − H]+) and to the right indicates the addition of a hydrogen at the cleavage site (i.e., cn// = [cn + 2H]+). The spectra have no expansion of the intensity axis; all peaks are shown to scale.

All trivalent lanthanide cations except europium (Eu) produce similar ETD fragmentation for [M + Met − H]2+ with the three peptides. Supplementary Figure S1 shows ETD of [M + Pr − H]2+ for [Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B. Despite a slightly lower efficiency, the type and intensity of product ions match those of fibrinopeptide B (Figure 2a). For [Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B, z7/+ forms from cleavage between the two adjacent glutamic acids residues, E7 and E8.

A different fragmentation pattern results from ETD on [M + Met − H]2+ for des-Arg14-[Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B. Non-metallated product ions are absent, as illustrated in Supplementary Figure S2 with Pr(III). Metallated c- and z-ions form, similar to the fragmentation of the other two peptides (Figure 2a and Supplementary Figure S1). In addition, like fibrinopeptide B, cleavage between E7 and E8 is not observed.

The only unique behavior is for Eu(III), where [M + Eu − H]2+ has low dissociation efficiency and almost no backbone cleavage. As shown in Figure 3a for fibrinopeptide B, the only significant products are the charge reduced ion, [M + Eu − H]+, from ETnoD and a water loss species. A similar effect is seen in Supplementary Figures S3 and S4 for the two peptide analogs.

Figure 3.

ETD mass spectra of (a) [M + Eu − H]2+, (b) [M + Eu]3+, and (c) [M + Eu + H]4+ for fibrinopeptide B produced by addition of Eu(III). Refer to the Figure 2 caption for an explanation of the color coding and prime symbols. The spectra have no expansion of the intensity axis; all peaks are shown to scale.

ETD on [M + Met]3+

Figure 2b shows that ETD on [M + Pr]3+ for fibrinopeptide B yields a mix of metallated and non-metallated c- and z-ions. Most have a charge of 1+, although a few 2+ ions form. The z-series are zn/+ and [zn + Pr]+. The only non-metallated c-ion is c4//+. All other c-ions are [cn/ + Pr]+, n = 7-13. Cleavage occurs at every residue except on the N-terminal side of the glutamic acid residue at position 7 (E7). Cleavage between the glutamic acid residues at positions 7 and 8 is minimal. The neutral losses are similar to those observed for [M + Met − H]2+.

With the exception of Eu(III), the identity of the lanthanide ion does not affect the ETD spectra of [M + Met]3+. Similar dissociation patterns and relative ion intensities are observed for fibrinopeptide B and its two analogs (Supplementary Figures S5 and S6). ETD fragmentation efficiency is highest for fibrinopeptide B and des-Arg14-[Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B; typically >90% of the selected precursor ion dissociates. [Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B has a slightly lower ETD efficiency of [M + Met]3+ but still has cleavage at every residue. High signal-to-noise ratios (S/N) and intense product ions allow for easy identification of ETD product ions in all spectra.

In contrast to the extensive sequence coverage from the other lanthanide ions, [M + Eu]3+ yields an intense ETnoD ion and a decreased amount of backbone cleavage for all three peptides, as shown in Figure 3b and Supplementary Figures S7 and S8.

ETD on [M + Met + H]4+

The most structurally informative ETD spectra were found for [M + Met + H]4+. A mix of non-metallated and metallated c- and z- ions form for fibrinopeptide B, as shown in Figure 2c. Product ions have 1+ and 2+ charges. Backbone cleavages occur between all residues and a high S/N allows for easy identification of ETD products. Non-metallated and metallated c- and z-series, as well as neutral losses, are the same as for [M + Met]3+.

Little variation is evident among the lanthanide cations for ETD of [M + Met + H]4+. A few non-metallated c-ions are absent for [M + Eu + H]4+ from fibrinopeptide B, but surprisingly full sequence coverage occurs, as is evident in Figure 3c. More than 90% of [M + Met + H]4+ dissociates for fibrinopeptide B (Figure 2c) and [Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B (Figure 4a). As for des-Arg14-[Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B, no measurable precursor was left after ETD on [M + Met + H]4+, as shown in Figure 4b. Similar extensive fragmentation and product ion formation is observed for ETD on [M + Met − H]4+ for all three peptides.

Figure 4.

ETD mass spectra of [M + Pr + H]4+ for (a) [Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B and (b) des-Arg14-[Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B. Refer to the Figure 2 caption for an explanation of the color coding and prime symbols. The spectra have no expansion of the intensity axis; all peaks are shown to scale.

In Figures 4a and 4b for ETD on [M + Met + H]4+ for [Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B and des-Arg14-[Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B, an intense c7//+ forms, which corresponds to cleavage between E7 and E8. In contrast, no c7//+ but only low intensity z7/+ and [c7/ + Pr]+ results from ETD on [M + Pr + H]4+ for fibrinopeptide B (Figure 2c). Thus, removal of cyclization on the N-terminal glutamic acid facilitates increased cleavage between the two glutamic acid residues.

Discussion

Impact of Metal Ion Properties

When discussing ETD on metal-cationized peptides, electronic properties are of importance. The trivalent lanthanide ions have an electronic configuration of [Xe]4fm 6s0, where m steadily increases from zero for the first element in the series (lanthanum, La) to fourteen for the final element in the series (lutetium, Lu) [66]. Changing electron configuration affects the solid-and solution-phase chemistries of the lanthanide series, although to a lesser extent than electronic configuration affects the transition metal series [66]. In several previous studies of ECD/ETD on metallated peptides, properties related to electronic configuration, such as ionization energy (IE), have been shown to affect fragmentation [39-41, 47]. For peptide complexes with divalent transition and alkaline earth metal ions, Liu and Håkansson [39] postulated that a lower second ionization energy (IE2) indicates that there can be more facile electron transfer from the metal ion to the peptide backbone following the initial electron capture by the metal ion. In support of this, they found that adduction of divalent metal ions with lower IE2 values (965-1563 kJ/mol) yielded more extensive backbone cleavage by ECD than metals with higher IE2 values (1649-1756 kJ/mol).

For trivalent metal ions, addition of an electron directly to the metal ion during ETD can result in the gas-phase metal ion being reduced from the 3+ state to 2+. This process relates to the third ionization energy (IE3). Across the lanthanide series, IE3 values increase in the range of 1850 to 2415 kJ/mol [66]. With IEs of this magnitude, a divalent metal ion would be unlikely to cause peptide backbone dissociation based on the work of Liu and Håkansson [39]; however, trivalent metal ions have the advantage of ETD/ECD fragmentation increasing as the charge on the precursor ion increases [30, 37, 38, 67]. For the lathanide series, outliers from a smooth upward IE3 trend are Eu (IE3 = 2404 kJ/mol [66]) and ytterbium, Yb (IE3 = 2415 kJ/mol [66]), where higher values occur because their divalent ions have the stability of half-filled and completely filled f-shells, respectively. (Disregarding Eu and Yu, the highest IE3 for a lanthanide is 2285 kJ/mol [66].) Therefore in ETD experiments, Eu(III) and Yb(III) may have a greater tendency to retain the electron and be reduced to 2+ ions. Several reports have found that direct metal reduction in ETD/ECD can compete with electron transfer to the peptide and restrict backbone dissociation [44, 51]. In the current work, the ETD spectra of metallated peptides vary little as the lanthanide metal ion is changed. (For example, see Supplementary Figure S12 for ETD on [M + Met + H]4+ involving four trivalent lanthanide ions.) The only exception is for Eu(III), as shown in Figure 3, which is discussed below. The fact that the IE3 values vary over a relatively small range in the lanthanide series may contribute to their general consistency in promoting ETD fragmentation.

The ability of other common trivalent metal ions to induce ETD fragmentation was considered. We have previously found that trivalent chromium, Cr(III), readily cationizes acidic and neutral peptides [58, 68, 69] and that during CID these Cr(III)-peptide ions undergo extensive sequence-informative fragmentation [68]. Also, Cr(III) readily binds to acidic peptides in solution [10, 70, 71]. However, Cr(III) proved to be a poor choice for sequencing fibrinopeptide B by ETD (see Supplementary Figure S9). Cleavage was inefficient and backbone fragmentation was restricted to a few sites near the C-terminus; instead, an intense ETnoD product, [M +Cr]2+, formed. This sequestered fragmentation is analogous to what Liu and Håkansson [39] observed for divalent metal ion-peptide complexes when IE2 was relatively high. Our Cr(III) result probably relates to the very high IE3 of 2987 kJ/mol [72] for Cr, which can lead to energetically favorable gas-phase retention of an electron to generate Cr(II) and to limited cleavage along the peptide backbone. Although fibrinopeptide B was not involved, we have also found that main group trivalent aluminum, Al(III), is a poor promoter of ETD fragmentation (Schaller-Duke, R.M, Cassady, C.J, unpublished results, 2016). This is consistent with the high IE3 of 2745 kJ/mol for Al [72]. In addition, we attempted to study trivalent iron, Fe(III), with fibrinopeptide B. These experiments were unsuccessful because the ESI signal of iron(III)-cationized peptide was unstable and irreproducible. We have encountered this problem previously [58, 69] and attribute it to iron(III) reduction to iron(II) in solution (reduction potential, E0 = +0.771 V [73]) during ESI. With an ESI source of similar design to our source (i.e., grounded needle with cations spraying into an electric field of negative polarity), Hoppilliard and coworkers [74] have also reported reduction of easily reduced metal cations.

Decreased ETD fragmentation efficiency and limited backbone cleavage is a recurring trend for [M + Eu − H]2+ and [M + Eu]3+ from the three peptides throughout this study. Williams and coworkers [50] also observed a lack of ECD product ion formation for peptides adducted to Eu(III). Eu(III) has an electronic configuration of [Xe]4f6 that becomes a highly stable [Xe]4f7 upon addition of one electron. This is indicated by the relatively high IE3 of Eu and the fact that it commonly forms divalent compounds [66]. However, Yb also acquires a stable electronic configuration, [Xe]4f14, upon single electron recombination, but as shown in Supplementary Figure S10, ETD of [M + Yb]3+ for fibrinopeptide B yields extensive sequence-informative fragmentation despite a relatively intense charge reduced ETnoD ion. The backbone cleavage ions are similar in type and intensity to those obtained with other lanthanide ions. Therefore, an additional factor needs to be considered to account for the differences in ETD fragmentation observed between Eu(III) and Yb(III) peptide-complexes. Inside the mass analyzer, the metal cations exist in the metal-peptide complexes formed during ESI and not in a free state. Thus, the chemistry of metal-peptide complexes will affect their ETD fragmentation. Several studies show that in aqueous and ammoniated complexes, E0 of Yb(III) is considerably lower than for Eu(III) [75-77]. Reduction of Eu(III) to Eu(II) has E0 of -0.36 V, while for Yb(III) this E0 is -1.05 V [73]. That is, in solution Eu(III) reduces more readily than Yb(III). Williams and coworkers referred to Eu(III) as an “electron trap” [50] because of its propensity to favorably undergo a one electron reduction in a “solvated” complex such as in aqueous media or, in this case, a peptide. During the ETD and ECD processes, in some instances, Eu(III) may be preferentially undergoing direct reduction instead of allowing the electron to be directed at the peptide backbone to facilitate normal ECD/ ETD N-Cα bond cleavage.

Like Eu(III), the divalent ion of copper, Cu(II), is easily reduced (E0 = +0.153V [73]) and exhibits different fragmentation patterns in peptide complexes than other members of its series. Chan [44] and Vachet [51] and their coworkers have postulated that metal ion reduction leads to changes in the coordination sphere of Cu(II) which contribute significantly to the fragmentation patterns observed by ETD/ECD. However, unlike Cu(II) and other transition metal ions with interactive outer d-orbitals, the f-orbitals of the lanthanides have weak overlap with binding ligands [66]. Therefore, lanthanide metal center reduction has minimal to no effect on orbital geometries [66]. As a consequence, we speculate that coordination sphere changes may have a less significant role in dissociation of peptide complexes for Eu(III) than for Cu(II).

For Eu(III), the extent of structurally-informative ETD fragmentation is dependent on the nature of the peptide-metal ion complex. Proton deficient [M + Eu − H]2+ (Figure 3a) generates no backbone cleavage ions and the peptide cannot be sequenced. In contrast, [M + Eu + H]4+ (Figure 3c) generates abundant product ions involving cleavage at every residue. Here, the extra proton is allowing backbone cleavage pathways to dominate the spectra and the impact of electron sequestration by Eu(III) is minimized. In an ETD study, Vachet and coworkers [51] found that the presence of an extra proton in conjunction with acidic residues to bind Cu(II) allowed increased peptide backbone cleavage; that is, the transfer of an electron to protonated peptide sites competed favorably with reduction of Cu(II). Likewise, in the current study, less metal reduction occurs during ETD of [M + Eu + H]4+ and instead c- and z-ion formation increases. In contrast, [M + Eu −H]2+ and [M + Eu]3+ lack an extra proton and undergo minimal, if any, backbone dissociation. In addition, the higher ionic charge on [M + Eu + H]4+ may play a role in its enhanced dissociation. Peptide fragmentation by ETD generally increases as the precursor ion charge increases, although this effect is complex and also relates to the types of amino acid residues present and the length of the peptide sequence [30, 37, 38].

While [M + Eu]3+ provides less sequence coverage by ETD (Figure 3b) than the other lanthanide ions, more product ions form in the current study than Williams and coworkers [50] observed by ECD for several other peptides. This difference may relate to fragmentation efficiency. In ECD, the percentage of the precursor ion that dissociates is limited by the ability of the electron beam to overlap with the analyte cations [78]. No such limitation exists in ETD (where a cation/anion reaction occurs), generally making the process more efficient. In addition, our Bruker HCTultra has a high capacity QIT that allows ions to cluster together and interact in a spherical cloud-like formation in the center of the mass analyzer [79]. This promotes a high degree of overlap between the peptide cations and the ETD reagent anions, which results in effective electron transfer and high fragmentation efficiencies.

From lanthanum (La) to lutetium (Lu), the ionic radius of the 3+ ion decreases from 103.2 pm for La to 86.1 pm for Lu [66]. This larger than normal decrease in the ionic radii is known as the “lanthanide contraction.” The 4f orbital acts as a poor shield against the nuclear charge exhibited on the 6s shells by the nucleus. This decrease in ionic radii can affect the chemistry of the trivalent lanthanide ions [66]. Surprisingly, the size of the trivalent metal cation causes no variation in the ETD fragmentation in the current study.

Dissociation Trends and Sequence Information

For the lanthanide ions other than Eu(III), all three precursor ions provide sequence-informative fragmentation. The trends, which are illustrated in Figure 2 with Pr(III), are that [M + Met + H]4+ yields ETD cleavage at every residue, [M + Met]3+ cleaves at almost every residue (with one or two exceptions), and [M + Met − H]2+ cleaves at almost every residue but with lower product ion intensities. Generally, ETD spectra of [M + Met]3+ are sufficient for sequencing. This precursor ion has the advantage of forming in abundance even in the absence of a basic arginine, lysine, or histidine residue on the peptide; for example, [M + Pr]3+ is the base peak in Figure 1c for ESI involving des-Arg14-[Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B. However, even better conditions for sequencing occur with [M + Met + H]4+, where proton adduction leads to more intense and wide-ranging fragmentation. In ESI on peptides, protons are postulated to initially bind to basic residues, with a preference for arginine [80-83]. Although the ESI process may have preferentially deposited the extra proton on the N-terminal arginine residue, that is not always its location in the ETD product ions. As seen in Figure 2 for fibrinopeptide B, cn//+, n = 2-6, occur in much greater intensity for the 4+ precursor than the 3+ and 2+ precursors; these ions contain no residues with basic side chains. Note that for the 3+ and 4+ precursors the additional proton does not change the product ion series; for example, the non-metallated c-series is cn//+ for both [M + Met]3+ and [M + Met + H]4+. Instead, the added proton increases the intensity of product ions from these series and causes more members of the series to be observed.

Variation in the ETD product ion series is a noteworthy aspect of this work. [M + Met]3+ and [M + Met + H]4+ yield the same product ion series, while [M + Met − H]2+ is unique. The metallated c-series is [cn/ + Met]+ for the 3+ and 4+ precursors, but [/cn + Met]+ for the 2+ precursor. This difference of two hydrogens can be explained by the proton deficiency of the precursor ion, [M + Met − H]2+.

The ETD z-series products are particularly interesting. While the 3+ and 4+ precursors generate zn/+, [zn + Met]+, and [zn + Met]2+, the proton deficient 2+ precursor yields z-ions with one more hydrogen, zn//+ and [zn/ + Met]+. The z-series routinely found in ETD and ECD is zn/+, which is a radical of the type [z + H]+· [31, 84]. In a high resolution Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance (FT-ICR) study of ECD on 15,000 mass spectra of tryptic peptides, Zubarev and coworkers [85] did not observe zn//+ formation but only zn/+ or occasionally zn+. In contrast, we found that ETD on [M + 2H]2+ from fibrinopeptide B and [Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B generates an extensive z-series that is almost exclusively zn//+. (A minor amount of z/+ forms but is ∼10% the intensity of z//+.) With no arginine residue, [M + 2H]2+ from des-Arg14-[Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B produces only two z-ions, both of which are the normal zn/+. (ETD spectra for [M + 2H]2+ are in Supplementary Figure S11.) Thus, ETD on both [M + Met − H]2+ and [M + 2H]2+ form the unusual zn//+ series for fibrinopeptide B and [Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B, but not for des-Arg14-[Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B. The additional hydrogen in zn//+ may be residing at the C-terminal arginine residue of fibrinopeptide B and of [Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B. However, this cannot be the only factor because many of the tryptic peptides studied by Zubarev [85] undoubtedly contain a C-terminal arginine residue. Instead, this unique fragmentation, which we have also observed during ETD of [M + 2H]2+ for other acidic peptides (Commodore, J.J, Cassady, C.J, unpublished results, 2016), appears to relate to the presence of several acidic residues in conjunction with a nearby basic residue. We are currently conducting additional studies on this effect with custom synthesized peptides. Salt bridge intermediates involving acidic and basic sites are known to affect peptide fragmentation [54-56, 86, 87]. It is possible that the sequences of fibrinopeptide B and its [Glu1] analog allow a salt bridge formation that impacts their electron-induced fragmentation pathways.

Throughout this study, all metallated product ions contain an acidic amino acid residue, which suggests attachment of the lanthanide cation at the acidic side chains. This is consistent with several studies suggesting that trivalent metal ions preferentially bind to acidic sites on peptides [50, 54-56, 58]. For example, in Figure 2 showing the ETD spectra of 2+, 3+, and 4+ precursors from fibrinopeptide B, only peptide fragments containing at least two acidic sites (i. e., glutamic acid or aspartic acid side chains and the C-terminal carboxylic acid group) are metallated. In their ECD study on several peptides, Williams and coworkers [50] also observed metal-adducted ions from peptide fragments containing at least one acidic amino acid residue.

The sequences of the peptides result in minor variations in the ETD spectra that relate to cleavages near acidic residues. For fibrinopeptide B with a cyclized N-terminal glutamic acid residue, ETD on [M + Met + H]4+ generates low intensity product ions, z7/+ and [c7/ + Pr]+, corresponding to cleavage between the two glutamic acid residues at E7 and E8, as shown in Figure 2c. In contrast, more intense peaks, c7//+ and z7/+, corresponding to the cleavage between E7 and E8 occur for ETD on [M + Met + H]4+ for [Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B and des-Arg14-[Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B (Figure 4). The two analogs have a non-cyclized glutamic acid residue at the N-terminus, which provides acidic sites at E1, D4, E7, and E8, as well as at the C-terminus. With fibrinopeptide B, there are acidic sites at only D4, E7, E8, and the C-terminus. The metallated product ions always contain two acidic sites, suggesting simultaneous coordination of the lanthanide ion to both locations. Because fibrinopeptide B has only four acidic sites there is a greater probability of coordination involving both E7 and E8, which might hinder cleavage between these residues. The presence of an additional acidic site at E1 in [Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B and des-Arg14-[Glu1]-fibrinopeptide may yield more possibilities for metal ion coordination, thus minimizing E7 and E8 simultaneous coordination and enhancing E7-E8 cleavage. The work of Williams and coworkers [50] also suggested simultaneous coordination of trivalent lanthanide cations to two acidic sites.

Isotopic composition of the metal ion influences the appearance of the ETD spectra. Six lanthanide metals have one major stable isotope in an abundance greater than 95%, Eu has two stable isotopes in near equal abundances, and the remaining lanthanide metals have multiple staple isotopes of significant intensities. Spectra from lanthanide metal ions with one major isotope have easily resolved peaks, which simplify interpretation; for example, see Figures 2, S12a, S12c, and S12d. In contrast, Supplementary Figure S12b is the ETD spectrum for [M + Sm + H]4+ from fibrinopeptide B. Sm(III) has seven major isotopes with the most abundant at 26.7% [73]. Ionic peak broadening and overlapping occurs when the lanthanide metal has several stable isotopes, which can reduce resolution and make interpretation more difficult. The only benefit to using a lanthanide metal with many isotopes is that the elucidation of metallated product ions is easier because the metal creates a characteristic isotopic distribution that is evident in the spectra.

Conclusions

Trivalent lanthanide cations readily adduct to the acidic fibrinopeptide B and its analogs to form [M +Met + H]4+, [M + Met]3+, and [M + Met − H]2+. These ions undergo ETD to generate abundant sequence-informative product ions and extensive peptide backbone cleavage. The intense signals of the multiply charged precursor ions and the high fragmentation efficiency of ETD yields spectra with high S/N, which is beneficial for automated techniques. For peptides lacking a highly basic amino acid residue, trivalent lanthanide ion adduction may be particularly useful because it provides ready formation of multiply charged peptide ions that can be subjected to ETD. In the current study, Pr(III) consistently produced intense metallated peptide ions and allowed for easy interpretation of ETD spectra, but any lanthanide metal ion with one major isotope is adequate for peptide analysis. In addition, metallated product ions can be easily confirmed using a companion metal such as Sm(III) that has multiple stable isotopes. The ability of multiply charged trivalent lanthanide-peptide complexes to undergo extensive ETD fragmentation could prove to be very useful in the sequencing of acidic peptides. Because peptide analysis in proteomics studies commonly involves liquid chromatographic (LC) separation of mixtures, we are currently exploring the addition of metal ions to LC eluents. This appears to be a feasible method for producing metallated peptide ions for study by tandem mass spectrometry.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the National Institute of Health (1R15GM109401A). Financial support for the purchase of the Bruker HCTultra was provided by a National Science Foundation Chemistry Research Instrumentation Facility grant (CHE-0639003). Dr. John Vincent is also thanked for providing several lanthanide nitrate salts and for helpful discussions on trivalent lanthanide metal ion chemistry.

References

- 1.Ebert RF, Bell WR. Assay of human fibrinopeptides by high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal Biochem. 1985;148:70–78. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90629-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edkins JS. The chemical mechanism of gastric secretion 1. J Physiol Lond. 1906;34:133–144. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1906.sp001146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dimaline R, Lee CM. Chicken gastrin - a member of the gastrin cck family with novel structure-activity-relationships. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:G882–G888. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1990.259.5.G882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pierotti AR, Prat A, Chesneau V, Gaudoux F, Leseney AM, Foulon T, Cohen P. N-arginine dibasic convertase, a metalloendopeptidase as a prototype of a class of processing enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6078–6082. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.6078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Speetjens JK, Parand A, Crowder MW, Vincent JB, Woski SA. Low-molecular weight chromium-binding substance and biomimetic [Cr3O(O2CH2CH3)6(H2O)3]+ do not cleave DNA under physiologically-relevant conditions. Polyhedron. 1999;18:2617–2624. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vincent JB. Elucidating a biological role for chromium at a molecular level. Acc Chem Res. 2000;33:503–510. doi: 10.1021/ar990073r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis CM, Vincent JB. Isolation and characterization of a biologically active chromium oligopeptide from bovine liver. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;339:335–343. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.9878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lapko VN, Jiang XY, Smith DL, Song PS. Posttranslational modification of oat phytochrome A: Phosphorylation of a specific serine in a multiple serine cluster. Biochemistry. 1997;36:10595–10599. doi: 10.1021/bi970708z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yagami T, Kitagawa K, Futaki S. Liquid secondary-ion mass spectrometry of peptides containing multiple tyrosine-O-sulfates. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 1995;9:1335–1341. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1290091403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Y, Watson HM, Gao J, Sinha SH, Cassady CJ, Vincent JB. Characterization of the organic component of low-molecular-weight chromium-binding substance and its binding of chromium. J Nutr. 2011;141:1225–1232. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.139147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jai-nhuknan J, Cassady CJ. Negative ion postsource decay time-of-flight mass spectrometry of peptides containing acidic amino acid residues. Anal Chem. 1998;70:5122–5128. doi: 10.1021/ac980577n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zubarev RA, Kelleher NL, McLafferty FW. Electron capture dissociation of multiply charged protein cations. A nonergodic process. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:3265–3266. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zubarev RA, Horn DM, Fridriksson EK, Kelleher NL, Kruger NA, Lewis MA, Carpenter BK, McLafferty FW. Electron capture dissociation for structural characterization of multiply charged protein cations. Anal Chem. 2000;72:563–573. doi: 10.1021/ac990811p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zubarev RA, Kruger NA, Fridriksson EK, Lewis MA, Horn DM, Carpenter BK, McLafferty FW. Electron capture dissociation of gaseous multiply-charged proteins is favored at disulfide bonds and other sites of high hydrogen atom affinity. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:2857–2862. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen X, Tureček F. The arginine anomaly: Arginine radicals are poor hydrogen atom donors in electron transfer induced dissociations. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:12520–12530. doi: 10.1021/ja063676o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zubarev RA, Haselmann KF, Budnik B, Kjeldsen F, Jensen F. Towards an understanding of the mechanism of electron-capture dissociation: A historical perspective and modern ideas. Eur J Mass Spectrom. 2002;8:337–349. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Syka JEP, Coon JJ, Schroeder MJ, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF. Peptide and protein sequence analysis by electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9528–9533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402700101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Syrstad EA, Tureček F. Toward a general mechanism of electron capture dissociation. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2005;16:208–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLafferty FW, Horn DM, Breuker K, Ge Y, Lewis MA, Cerda BA, Zubarev RA, Carpenter BK. Electron capture dissociation of gaseous multiply charged ions by Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2001;12:245–249. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(00)00223-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooper HJ, Håkansson K, Marshall AG. The role of electron capture dissociation in biomolecular analysis. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2005;24:201–222. doi: 10.1002/mas.20014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leymarie N, Costello CE, O'Connor PB. Electron capture dissociation initiates a free radical reaction cascade. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:8949–8958. doi: 10.1021/ja028831n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mirgorodskaya E, Roepstorff P, Zubarev RA. Localization of O-glycosylation sites in peptides by electron capture dissociation in a Fourier transform mass spectrometer. Anal Chem. 1999;71:4431–4436. doi: 10.1021/ac990578v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi SDH, Hemling ME, Carr SA, Horn DM, Lindh I, McLafferty FW. Phosphopeptide/phosphoprotein mapping by electron capture dissociation mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2001;73:19–22. doi: 10.1021/ac000703z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelleher NL, Zubarev RA, Bush K, Furie B, Furie BC, McLafferty FW, Walsh WT. Localization of labile posttranslational modifications by electron capture dissociation: The case of γ-carboxyglutamic acid. Anal Chem. 1999;71:4250–4253. doi: 10.1021/ac990684x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mann M, Jensen ON. Proteomic analysis of post-translational modifications. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:255–261. doi: 10.1038/nbt0303-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stensballe A, Jensen ON, Olsen JV, Haselmann KF, Zubarev RA. Electron capture dissociation of singly and multiply phosphorylated peptides. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2000;14:1793–2000. doi: 10.1002/1097-0231(20001015)14:19<1793::AID-RCM95>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao C, Sethuraman M, Clavreul N, Kaur P, Cohen RA, O'Connor PB. Detailed map of oxidative post-translational modifications of human P21Ras using Fourier transform mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2006;78:5134–5142. doi: 10.1021/ac060525v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zubarev RA. Electron capture dissociation LC/MS/MS for bottom-up proteomics. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;492:413–416. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-493-3_25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coon JJ. Collisions or electrons? Protein sequence analysis in the 21st century. Anal Chem. 2009;81:3208–3215. doi: 10.1021/ac802330b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Good DM, Wirtala M, McAlister GC, Coon JJ. Performance characteristics of electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:1942–1951. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700073-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tureček F, Julian RR. Peptide radicals and cation radicals in the gas phase. Chem Rev. 2013;113:6691–6733. doi: 10.1021/cr400043s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dongre AR, Jones JL, Somogyi A, Wysocki VH. Influence of peptide composition, gas-phase basicity, and chemical modification on fragmentation efficiency: Evidence for the mobile proton model. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:8365–8374. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kjeldsen F, Giessing AMB, Ingrell CR, Jensen ON. Peptide sequencing and characterization of post-translational modifications by enhanced ion-charging and liquid chromatography electron-transfer dissociation tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2007;79:9243–9252. doi: 10.1021/ac701700g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wells JM, Stephenson JL, Jr, McLuckey SA. Charge dependence of protonated insulin decompositions. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2000;203:A1–A9. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Madsen JA, Brodbelt JS. Comparison of infrared multiphoton dissociation and collision-induced dissociation of supercharged peptides in ion traps. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2009;20:349–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Good DM, Wirtala M, McAlister GC, Coon JJ. Performance characteristics of electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:1942–1951. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700073-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chalkley RJ, Medzihradszky KF, Lynn AJ, Baker PR, Burlingame AL. Statistical analysis of peptide electron transfer dissociation fragmentation mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2010;82:579–584. doi: 10.1021/ac9018582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharma V, Eng JK, Feldman S, von Haller PD, MacCoss MJ, Noble WS. Precursor charge state prediction for electron transfer dissociation tandem mass spectra. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:5438–5444. doi: 10.1021/pr1006685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu H, Håkansson K. Divalent metal ion-peptide interactions probed by electron capture dissociation of trications. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2006;17:1731–1741. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2006.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu H, Håkansson K. Electron capture dissociation of tyrosine O-sulfated peptides complexed with divalent metal cations. Anal Chem. 2006;78:7570–7576. doi: 10.1021/ac061352c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fung YME, Liu H, Chan TWD. Electron capture dissociation of peptides metalated with alkaline-earth metal ions. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2006;17:757–771. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2006.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen X, Chan WYK, Wong PS, Yeung HS, Chan TWD. Formation of peptide radical cations (M+·) in electron capture dissociation of peptides adducted with group IIB metal ions. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2011;22:233–244. doi: 10.1007/s13361-010-0035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen X, Fung YME, Chan WYK, Wong PS, Yeung HS, Chan TWD. Transition metal ions: Charge carriers that mediate the electron capture dissociation pathways of peptides. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2011;22:2232–2245. doi: 10.1007/s13361-011-0246-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen X, Wang Z, Li W, Wong YLE, Chan TWD. Effect of structural parameters on the electron capture dissociation and collision-induced dissociation pathways of copper(II)-peptide complexes. Eur J Mass Spectrom. 2015;21:649–657. doi: 10.1255/ejms.1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen X, Liu G, Wong EYL, Deng L, Wang Z, Li W, Chan TWD. Dissociation of trivalent metal ion (Al3+, Ga3+, In3+ and Rh3+)–peptide complexes under electron capture dissociation conditions. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2016;30:705–710. doi: 10.1002/rcm.7502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Voinov VG, Hoffman PD, Bennett SE, Beckman JS, Barofsky DF. Electron capture dissociation of sodium-adducted peptides on a modified quadrupole/time-of-flight mass spectrometer. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2015;26:2096–2104. doi: 10.1007/s13361-015-1230-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kleinnijenhuis AJ, Mihalca R, Heeren RMA, Heck AJR. Atypical behavior in the electron capture induced dissociation of biologically relevant transition metal ion complexes of the peptide hormone oxytocin. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2006;253:217–224. [Google Scholar]

- 48.van der Burgt YEM, Palmblad M, Dalebout H, Heeren RMA, Deelder AM. Electron capture dissociation of peptide hormone changes upon opening of the tocin ring and complexation with transition metal cations. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2009;23:31–38. doi: 10.1002/rcm.3849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Iavarone AT, Paech K, Williams ER. Effects of charge state and cationizing agent on the electron capture dissociation of a peptide. Anal Chem. 2004;76:2231–2238. doi: 10.1021/ac035431p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Flick T, Donald W, Williams E. Electron capture dissociation of trivalent metal ion-peptide complexes. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2013;24:193–201. doi: 10.1007/s13361-012-0507-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dong J, Vachet RW. Coordination sphere tuning of the electron transfer dissociation behavior of Cu(II)-peptide complexes. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2012;23:321–329. doi: 10.1007/s13361-011-0299-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Asakawa D, Takeuchi T, Yamashita A, Wada Y. Influence of Metal–Peptide complexation on fragmentation and inter-fragment hydrogen migration in electron transfer dissociation. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2014;25:1029–1039. doi: 10.1007/s13361-014-0855-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Asakawa D, Wada Y. Electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry of peptides containing free cysteine using group XII metals as a charge carrier. J Phys Chem B. 2014;118:12318–12325. doi: 10.1021/jp502818u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Prell JS, Flick TG, Oomens J, Berden G, Williams ER. Coordination of trivalent metal cations to peptides: Results from IRMPD spectroscopy and theory. J Phys Chem A. 2009;114:854–860. doi: 10.1021/jp909366a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shi T, Hopkinson AC, Siu KWM. Coordination of triply charged lanthanum in the gas phase: Theory and experiment. Chem Eur J. 2007;13:1142–1151. doi: 10.1002/chem.200601074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shi T, Siu KWM, Hopkinson AC. Generation of [La(peptide)]3+ complexes in the gas phase: Determination of the number of binding sites provided by dipeptide, tripeptide, and tetrapeptide ligands. J Phys Chem A. 2007;111:11562–11571. doi: 10.1021/jp0752163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shvartsburg AA, Jones RC. Attachment of metal trications to peptides. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2004;15:406–408. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Feng C, Commodore JJ, Cassady CJ. The use of chromium(III) to supercharge peptides by protonation at low basicity sites. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2015;26:347–358. doi: 10.1007/s13361-014-1020-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hunter EP, Lias SG. Proton Affinity Evaluation. In: Linstrom PJ, Mallard WG, editors. NIST Chemistry WebBook, NIST Standard Reference Database Number 69. National Institute of Standards and Technology; Gaithersburg MD: 20899, (retrieved February 5, 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roepstorff P, Fohlman J. Proposal for a common nomenclature for sequence ions in mass spectra of peptides. Biomed Mass Spectrom. 1984;11:601. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200111109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Biemann K. Contributions of mass-spectrometry to peptide and protein-structure. Biomed Environ Mass Spectrom. 1988;16:99–111. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200160119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chung TW, Hui R, Ledvina A, Coon JJ, Tureček F. Cascade dissociations of peptide cation-radicals. Part 1. scope and effects of amino acid residues in penta-, nona-, and decapeptides. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2012;23:1336–1350. doi: 10.1007/s13361-012-0408-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Han H, Xia Y, McLuckey SA. Ion trap collisional activation of c and z• ions formed via gas-phase ion/ion electron-transfer dissociation. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:3062–3069. doi: 10.1021/pr070177t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fung YME, Chan TWD. Experimental and theoretical investigations of the loss of amino acid side chains in electron capture dissociation of model peptides. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2005;16:1523–1535. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xia Q, Lee M, Rose C, Marsh A, Hubler S, Wenger C, Coon J. Characterization and diagnostic value of amino acid side chain neutral losses following electron-transfer dissociation. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2011;22:255–264. doi: 10.1007/s13361-010-0029-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cotton S. Lanthanide and Actinide Chemistry. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.; West Sussex, England: 2006. pp. 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Frese CK, Altelaar AFM, Hennrich ML, Nolting D, Zeller M, Griep-Raming J, Heck AJR, Mohammed S. Improved peptide identification by targeted fragmentation using CID, HCD and ETD on an LTQ-orbitrap velos. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:2377–2388. doi: 10.1021/pr1011729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pu D, Vincent JB, Cassady CJ. The effects of chromium(III) coordination on the dissociation of acidic peptides. J Mass Spectrom. 2008;43:773–781. doi: 10.1002/jms.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Watson HM, Vincent JB, Cassady CJ. Effects of transition metal ion coordination on the collision-induced dissociation of polyalanines. J Mass Spectrom. 2011;46:1099–1107. doi: 10.1002/jms.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Davis CM, Vincent JB. Chromium oligopeptide activates insulin receptor tyrosine kinase activity. Biochemistry. 1997;36:4382–4385. doi: 10.1021/bi963154t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sun Y, Ramirez J, Woski SA, Vincent JB. The binding of trivalent chromium to low-molecular-weight chromium-binding substance (LMWCr) and the transfer of chromium from transferrin and Cr(pic)3 to LMWCr. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2000;5:129–136. doi: 10.1007/s007750050016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kramida A, Ralchenko Y, Reader J. Atomic Spectra Database. In: NIST ASD Team, editor. NIST Atomic Spectra Database (Ver 5.2) NIST, National Institute of Standards and Technology; Gaithersburg MD: 20899, (retrieved May 17, 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lide DR, editor. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. 73rd. CRC Press; Cleveland, OH: 1992-1993. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lavanant H, Virelizier H, Hoppilliard Y. Reduction of copper(II) complexes by electron capture in an electrospray ionization source. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1998;9:1217–1221. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Amorello D, Romano V, Zingales R. The formal redox potential of the Yb(III, II) couple at 0 degrees C in 3.22 molal NaCl medium. Ann Chim. 2004;94:113–121. doi: 10.1002/adic.200490030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Walters GC, Pearce D. The potential of the Yb+++ -Yb++ electrode. J Am Chem Soc. 1940;62:3330–3332. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Laitinen H, Taebel W. Europium and ytterbium in rare earth mixtures: Polarographic determination. Ind Eng Chem Anal Ed. 1941;13:825–829. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tsybin YO, Håkansson P, Budnik BA, Haselmann KF, Kjeldsen F, Gorschkov M, Zubarev RA. Improved low-energy electron injection systems for high rate electron capture dissociation in Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2001;15:1849–1854. doi: 10.1002/rcm.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kaplan D, Brekenfeld A, Hartmer R, Ledertheil T, Gebhardt C, Schubert M. Bruker Daltonics Technical Notes. Bruker Daltonics; Technical Note #24 Extending the Capacity in Modern Spherical High Capacity Ion Traps (HCT) retrieved February 19, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Suckau D, Shi Y, Beu SC, Senko MW, Quinn JP, Wampler FM, McLafferty FW. Coexisting stable conformations of gaseous protein ions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:790–793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.3.790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Loo JA, Edmonds CG, Udseth HR, Smith RD. Effect of reducing disulfide-containing proteins on electrospray ionization mass spectra. Anal Chem. 1990;62:693–698. doi: 10.1021/ac00206a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chowdhury SK, Katta V, Chait BT. Probing conformation changes in proteins by mass spectrometry. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:9012–9013. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Guevremont R, Siu KWM, Le Blanc JCY, Berman SS. Are the electrospray mass spectra of proteins related to their aqueous solution chemistry? J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1992;3:216–224. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(92)87005-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhurov KO, Fornelli L, Wodrich MD, Laskay UA, Tsybin YO. Principles of electron capture and transfer dissociation mass spectrometry applied to peptide and protein structure analysis. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:5014–5030. doi: 10.1039/c3cs35477f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Savitski MM, Kjeldsen F, Nielsen ML, Zubarev RA. Hydrogen rearrangement to and from radical z fragments in electron capture dissociation of peptides. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2007;18:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Oh H, Breuker K, Sze SK, Ge Y, Carpenter BK, McLafferty FW. Secondary and tertiary structures of gaseous protein ions characterized by electron capture dissociation mass spectrometry and photofragment spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15863–15868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212643599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lee SW, Kim HS, Beauchamp JL. Salt bridge chemistry applied to gas-phase peptide sequencing: Selective fragmentation of sodiated gas-phase peptide ions adjacent to aspartic acid residues. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:3188–3195. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.