Abstract

The Drosophila protein Jim Lovell (Lov) is a putative transcription factor of the BTB/POZ (Bric- a-Brac/Tramtrack/Broad/ Pox virus and Zinc finger) domain class that is expressed in many elements of the developing larval nervous system. It has roles in innate behaviors such as larval locomotion and adult courtship. In performing tissue-specific knockdown with the Gal4-UAS system we identified a new behavioral phenotype for lov: larvae failed to burrow into their food during their growth phase and then failed to tunnel into an agarose substratum during their wandering phase. We determined that these phenotypes originate in a previously unrecognized role for lov in the tracheae. By using tracheal-specific Gal4 lines, Lov immunolocalization and a lov enhancer trap line, we established that lov is normally expressed in the tracheae from late in embryogenesis through larval life. Using an assay that monitors food burrowing, substrate tunneling and death we showed that lov tracheal knockdown results in tracheal fluid-filling, producing hypoxia that activates the aberrant behaviors and inhibits development. We investigated the role of lov in the tracheae that initiates this sequence of events. We discovered that when lov levels are reduced, the tracheal cells are smaller, more numerous and show lower levels of endopolyploidization. Together our findings indicate that Lov is necessary for tracheal endoreplicative growth and that its loss in this tissue causes loss of tracheal integrity resulting in chronic hypoxia and abnormal burrowing and tunneling behavior.

Introduction

During their rapid growth period, Drosophila larvae burrow into their food, keeping only their posterior spiracles exposed at the food surface. As they transition from feeding to pupation, the larvae undertake a wandering phase in which they move away from food and seek out a site to settle for the prepupal and pupal molts. This wandering phase is a vulnerable period in the life cycle when exposure to environmental risks such as desiccation or predators can occur [1, 2]. Previous studies have established that wandering larvae will dig through a relatively soft substratum, creating tunnels, rather than moving across the surface [3]. This behavior may thus represent an innate defensive tactic. In general, there has been little analysis of this tunneling behavior, although a recent study demonstrated that it is subject to evolutionary modification [4]. Unexpectedly, in pursuing the roles of the Drosophila gene jim lovell (lov) we have discovered a link between this gene and larval burrowing and tunneling behaviors.

Our prior studies have already identified roles for lov in other larval and adult behaviors [5, 6] and suggested routes by which lov might affect these responses. lov encodes a putative transcription factor of the BTB/POZ domain family [7] and immunolocalization studies in embryogenesis established that Lov is expressed in the nuclei of many subsets of neurons in the PNS and CNS late in their development [6]. It seems probable therefore that lov acts to specify the terminal differentiation of particular classes of neurons and that its roles in behavior reflect these functions.

In order to dissect out the individual roles of lov in different subsets of neurons we undertook neuronal cell-type specific knockdown of lov, using the Gal4 system [8] in combination with lov RNAi. A series of neuron-specific Gal4 lines were screened for their effects on development and behavior when driving lov RNAi. Given that lov is expressed in almost all of the external sense organ (eso) neurons of the embryonic PNS we particularly sought Gal4 drivers that would express lov RNAi uniquely in eso lineages. The transcription factor Cut is essential for the maintenance of eso lineages [9] in both the embryo and the adult wing margin [10]. Regions of the cut locus that drive expression in the embryonic esos have been identified [11], but no cut-Gal4 driver that expresses specifically in these esos has been generated. However, a cut-Gal4 driver that directs transcription in the esos of the adult wing margin is available [10, 12] (Blochlinger, communication to Flybase FBrf0125080). This driver, termed here cut(ue)-Gal4 to denote the cut upstream enhancer it contains, was therefore included in our screen.

In contrast to the other Gal4 lines tested with lov RNAi, cut(ue)-Gal4 produced partial lethality in the larval phase that proved to be associated with an absence of burrowing and tunneling behaviors. In investigating these behaviors we uncovered a new role for lov in the growth of the larval tracheae that appears to be the origin of these behavioral defects. The damage produced by tracheal lov knockdown leads to hypoxia, which has been shown previously to cause larvae to exit their food burrows [13]. We show here that substratum tunneling in the wandering phase is also inhibited by hypoxia, thus establishing that both behaviors reflect the tracheal function of lov.

Results

Co-expression of cut(ue)-Gal4 and lov in the tracheal epithelial cells

Three lov RNAi lines were available from the Drosophila RNAi Consortia (two from the TRiP Center at Harvard Medical School and one from the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center) for these studies. We used Semi-Q RT-PCR to assess the effectiveness of these constructs at depleting lov RNA in the late embryonic nervous system when driven by the elav-Gal4 driver (S1 Fig). The Valium 20 lov RNAi construct (HMSO01126) from the TRiP facility proved most effective and was used as the lov RNAi construct for all the studies described here.

We initially screened for effects of lov RNAi driven by multiple neuronal drivers, and all but one produced behavioral anomalies (such as defective larval locomotion or adult courtship) without affecting overall viability. The unique lethality seen for cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi animals was therefore investigated further, beginning with a characterization of the early cut(ue)-Gal4 expression pattern. Using UAS-mCherry as a reporter [14], we determined that, in contrast to our expectation, this driver shows no neural expression in embryonic or larval life, but rather the Gal4 pattern is entirely limited to the epithelial cells of the tracheal system and the attached tracheoblasts (Fig 1B and 1F). The tracheoblasts are clusters of cells destined to generate elements of the adult tracheal system [15]. Further, the Gal4 expression under cut(ue)-Gal4 is highly regional within the tracheal dorsal trunks (DTs). It is largely limited to the three posterior sections, with weak expression in metamere Tr9 and very strong expression in i) metamere Tr10, ii) the connection between the DTs posterior to Tr10 (termed here the “bridge”), and iii) the final segment of the DTs adjacent to the spiracles (Fig 1B and 1G). Cut is a homeobox transcription factor that functions in the differentiation of many cell types and derives from a complex locus spanning 200 kb on the X chromosome (7B4-6) [11, 16]. Its role in the larval tracheae and tracheoblasts has been studied previously [17–19] and one cut-Gal4 enhancer trap line (PG142) that gives Gal4 expression in the tracheae and other cell types is known and used within the tracheal community [20]. However the 2.7 kb DNA fragment used to prepare the cut(ue)-Gal4 line, which lies more than 80 kb upstream of the cut coding sequence, was not previously known to regulate expression in the larval airways.

Fig 1. Larval expression patterns of the Gal4 drivers used in these studies.

(a-c) DIC and fluorescence images of first instar larvae expressing UAS-mCherry driven by lov91Y-Gal4 (a), cut(ue)-Gal4 (b), and btl-Gal4 (c). Identical exposure conditions were used for the fluorescence images to reveal the differences in expression levels for the three Gal4 lines. lov91Y-Gal4 shows neural expression and faint activity in the tracheal DT epithelial cells. The bright dots of fluorescence in (a) are either fusion cells of the DTs or nuclei of peripheral neurons. (d) shows lov91Y-Gal4 expression in the epithelial cells and fusion cells (FC) of a third instar larval DT, (e) shows Lov immunostaining in DT nuclei at the same larval stage, (f) shows expression of cut(ue)-Gal4 in a cluster of tracheoblast cells (TB) in a first instar larvae, (g) shows high expression of cut(ue)-Gal4 in Tr10 of the DTs, the bridge (B), and the posterior section of the DTs adjacent to the spiracles. Scale bars = 50 μm. CNS = central nervous system, DT = dorsal trunks, SG = salivary glands.

That cut(ue)-Gal4 produces larval lethality when driving lov RNAi clearly indicates that lov is also expressed in the embryonic/larval tracheal system. Our prior analysis of embryonic Lov expression did not detect Lov protein in the developing tracheae [6], but formation of the impermeable cuticle prevents protein immunolocalization late in embryogenesis when the tracheae mature. As an alternative approach, we examined the early expression pattern for Gal4 produced by the lov PGawB enhancer trap [8] mutation lov91Y-Gal4. Previously, we investigated the Gal4 pattern from this insertion in the adult brain, in connection with its effects on adult gravitaxis behavior [5]. Using a UAS-mCherry reporter, no Gal4 expression was detected for lov91Y-Gal4 in early embryogenesis, but later in development, mCherry expression faithfully mirrored the expression pattern of Lov in the nervous system that we have characterized previously [6]. However, in addition, faint mCherry expression was detected in all the epithelial cells of the tracheae in the very final stages of embryogenesis. Fluorescence was strongest in the fusion cells whose role is to fuse the individual segmental sections of the tracheal DTs into continuous tubes (Fig 1A and 1D). The weak tracheal epithelial expression continued beyond hatching throughout the larval stages (Fig 1D).

We confirmed that this lov91Y-Gal4 expression in the tracheae is a faithful representation of lov gene activity by staining third instar larval tracheae with Lov antibody. Nuclear Lov staining was detectable in all the epithelial cells and fusion cells of the DTs (Fig 1E). Our prior studies showed that by the end of embryogenesis, expression of Lov in many neural cell types ceases. In particular only a small subset of neurons in the PNS continues to express Lov in the larval stages. We found that in lov91Y-Gal4, this subset of the neurons also expresses Gal4 in the larval period (data not shown). We conclude that lov91Y-Gal4 faithfully reports the lov expression pattern from late embryogenesis into larval life and reveals both neural and tracheal lov expression at these stages. The Lov tracheal expression pattern includes the regions of the tracheae in which cut(ue)-Gal4 is active. Thus the lethality of cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae reflects previously unknown activity in the tracheae for both lov and the cut(ue)-Gal4 construct.

A range of behavioral and developmental phenotypes for lov knockdown in the tracheae identified using a burrowing/tunneling assay

Initial observation of cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae indicated two behavioral abnormalities: they stayed away from their food and did not tunnel into an agarose substratum during wandering. To further characterize and quantitate these behaviors and to confirm their origin in lov knockdown in the tracheae, we generated and used an assay that assesses larval food burrowing, substratum tunneling, and overall development (Material and Methods) and examined larvae in which several Gal4 lines expressing in the tracheal system were used to drive lov RNAi. Ultimately, detailed studies were performed for three drivers—breathless (btl)-Gal4, which is expressed throughout the tracheal system from early in its inception in embryogenesis [21], cut(ue)-Gal4 and lov91Y-Gal4. The PG142 Gal4 line was not used because this driver also gave Gal4 expression in the larval musculature. The expression patterns of the three chosen Gal4 lines in first instar larvae are compared in Fig 1. These patterns were imaged using identical exposure times so as to convey the relative strengths of Gal4 expression. Gal4 drivers for the developing posterior spiracles [22] produced no effects, confirming our finding that lov91Y-Gal4 > UAS mCherry larvae do not express mCherry in these spiracles (data not shown).

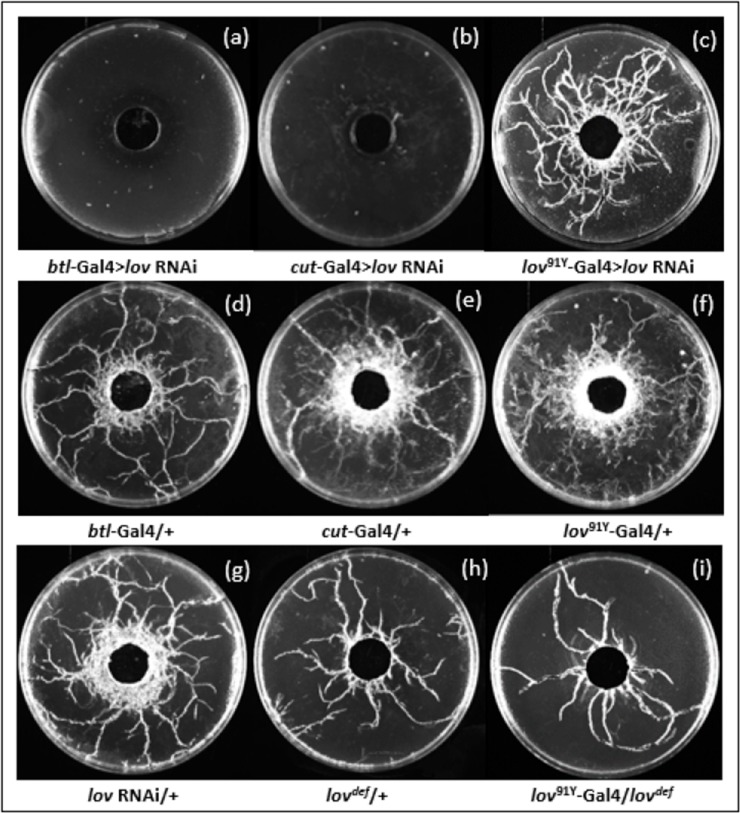

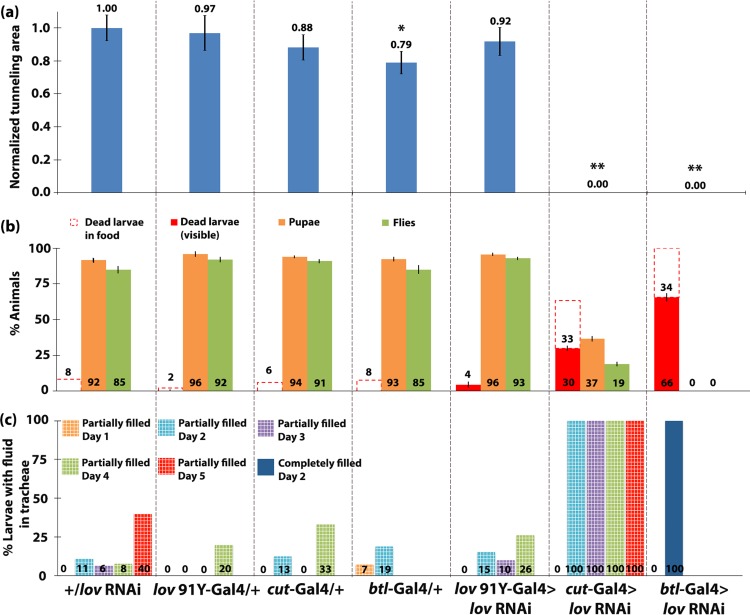

lov tracheal knockdown with the three Gal4 lines produced effects of differing severity on larval growth and behavior. Fig 2 shows images of tunneling assay plates for the key genotypes and Fig 3 and S2 Fig show quantitation of food burrowing, substratum tunneling and survival to pupation and adulthood for these larvae and other relevant genotypes. For cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi, about half of the larvae were found away from their food in the first 2–3 days after hatching (S2 Fig) and they showed a dispersion in size as they grew, with some larvae almost normal in size and others noticeably smaller than controls. By day 5 after hatching ~30% of the larvae had died and a further ~30% died before pupation (Fig 3B). Strikingly, those that reached wandering phase showed no tunneling at all in the agarose substratum (Fig 2B). Only ~ 20% of the larvae survived to adulthood. The effects of lov knockdown with btl-Gal4 were even more detrimental. Larvae were sluggish and showed very little growth, with ~65% dying outside the food during days 1–5 after hatching (Fig 3B and S2 Fig). As for cut(ue)-Gal4, no larvae tunneled in the agarose substratum (Fig 2A), but in contrast to cut(ue)-Gal4, no larvae survived long enough to attempt pupation. For lov91Y-Gal4 > lov RNAi, essentially no defects in the parameters measured were detected: larvae grew and developed to adults like controls, burrowing in their food and tunneling during wandering in a wild type manner (Figs 2C,3A and 3B).

Fig 2. Tunneling behavior of various genotypes examined in these studies.

Images of cleaned agarose plates from tunneling assays for key genotypes are shown. Tunneling was quantitated using Image J. Five control genotypes (panels (d)-(h)) show robust tunneling. lov91Y-Gal4 > RNAi larvae show comparable tunneling activity (panel (c)) but tunneling is completely absent for cut(ue)-Gal4 > RNAi and btl-Gal4 > RNAi larvae (panels (a) and (b). lov91Y-Gal4 /lov def larvae show limited tunneling behavior (panel (i)).

Fig 3. Failure to burrow, tunnel and survive to adulthood correlate strongly with fluid accumulation in the tracheae.

(a) Quantitation of tunneling was performed as described in Material and Methods for the genotypes shown. Mean values ± SEMs for the tunneling areas were calculated and then normalized to the value for the +/lov RNAi control. P values, Student’s t-test, * = P< 0.01, ** = P<0.00001, compared to +/ lov RNAi control. b) For larvae subjected to the burrowing/tunneling assay, the average percentage that died in the food, or outside the food (an indication of failure to burrow) was determined, in addition to the average percentage that pupated and the average percentage that emerged as adults. (c) Larvae of the same genotypes as those used for burrowing/tunneling assays, were imaged daily and the images were used to assess accumulation of fluid in the DTs (see Material and Methods). The percentages of larvae with partially fluid-filled DTs (checkered bars) or completely fluid-filled DTs (solid bars) on days 0–5 post-hatching are shown.

The phenotypic differences noted for the three Gal4 lines correlate well with their differences in strength and location of Gal4 expression. As shown in Fig 1, cut(ue)-Gal4 expression is very weak in most of the tracheal network, but is strong in the most posterior sections of the tracheal DTs, close to the spiracles. btl-Gal4 and lov91Y-Gal4 are expressed throughout the tracheal epithelial cells but lov91Y-Gal4 expression does not begin until the tracheal system is fully formed and is much weaker than btl-Gal4 expression (Fig 1). To address whether the behavioral and developmental differences seen between the lines result from differences in lov knockdown, all three lines were also tested in a lov hemizygous background (Fig 4).

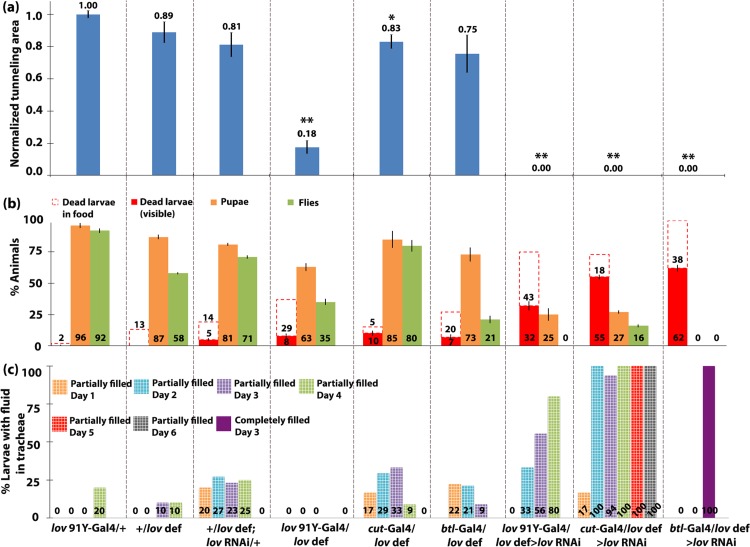

Fig 4. Correlation of failure to burrow, tunnel, and survive to adulthood, with tracheal fluid-filling in lov hemizygous genotypes.

Data for the experimental and control genotypes as in Fig 3 in a lov hemizygous background. All data were generated and shown as in Fig 3, except that in (a) the quantitated tunneling areas are normalized to the value of lov91Y-Gal4 /+. P values, Student’s t-test, * = P< 0.01, ** = P<0.00001, compared to the lov91Y -Gal4 /+ control. Note i) in the hemizygous condition, lov91Y -Gal4 /lov def > lov RNAi larvae fail to tunnel and ii) lov91Y -Gal4 /lov def larvae show reduced tunneling despite having air-filled tracheae.

With one copy of the genomic lov gene removed, lov91Y-Gal4/lov def > lov RNAi larvae showed behavioral/development effects similar to those seen with the other tracheal Gal4 drivers in a wild type background, including a complete failure to tunnel and considerable larval death away from the food (Fig 4 and S2 Fig). The cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi phenotype was also enhanced in lov hemizygotes, resulting in growth, behavior and viability defects more like those seen with btl-Gal4 (Fig 4 and S2 Fig) in a wild type lov background. The phenotype of btl-Gal4/ lov def > lov RNAi was not significantly different to that of btl-Gal4 > lov RNAi. These findings indicate a strong correlation between extent of lov knockdown in the tracheae and the behavioral and developmental effects seen.

Strong correlations between growth, behavior and tracheal damage

We examined the state of the larval tracheae for the various genotypes described above. Normally, air present in the tracheae causes light refraction and the outlines of the tracheal walls are highly visible as black lines through the larval body wall. In contrast when the tracheae are fluid-filled, the tracheae are almost invisible against the hemolymph-filled larval interior. The tracheae contain fluid at the end of embryogenesis but very shortly before hatching, they are inflated by a fluid removal process thought to involve the pickpocket class of ion channels [23]. Notably, in all larvae expressing lov RNAi in the tracheae, including the most strongly affected genotype, btl-Gal4/lov def > lov RNAi, the tracheae were water-tight and air-filled immediately after hatching. This finding indicates that lov plays no role in the initial inflation of the tracheae.

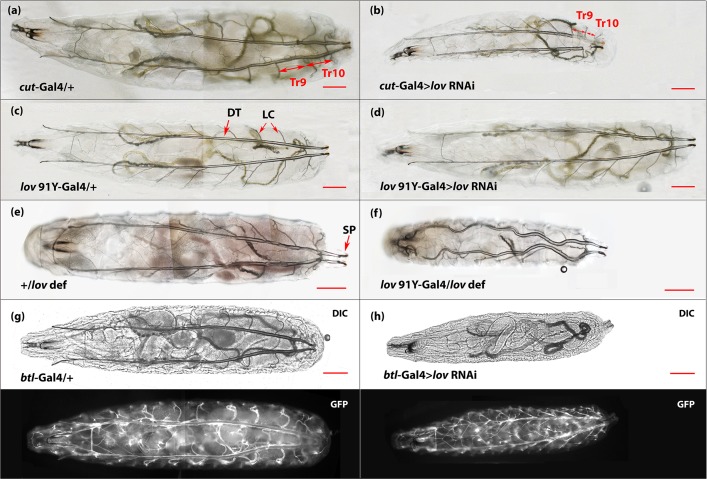

However, beyond hatching, fluid accumulation in the tracheae was seen amongst the genotypes studied. Figs 3 and 4 present quantitation of the tracheal fluid-filling for all genotypes examined and Fig 5 shows tracheal images for larvae of the key genotypes studied. The extent of larval tracheal fluid-filling correlated strongly with the growth and behavioral phenotypes described above. Negligible fluid accumulation was seen in genotypes that grew, burrowed, and tunneled normally, including lov91Y-Gal4 > lov RNAi. In contrast, all but one genotype (see below) that showed poor growth, failed burrowing and tunneling, and high pre-adult death showed strong penetrance of the tracheal fluid-filling phenotype. For btl-Gal4 > lov RNAi and btl-Gal4/lov def > lov RNAi larvae, which show the most severe developmental effects, the entire tracheal system becomes fluid-filled as early as day 2 after hatching in 100% of the larvae (Fig 5). In cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae, although the fluid-filling phenotype is 100% penetrant, the expressivity is more limited than in btl-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae (Figs 3–5). Typically only short regions of the DTs, corresponding to the regions showing high Gal4 expression under the cut(ue)-Gal4 driver (Fig 1) are fluid-filled. This more limited tracheal damage probably underlies the ability of some of these larvae to reach wandering stage and express the failed tunneling phenotype.

Fig 5. Fluid-filling of the DTs in larvae of the genotypes studied.

Bright field images of dorsal views of control (left-hand column) and experimental (right-hand column) second instar larvae for the three Gal4 > lov RNAi genotypes studied and for lov91Y -Gal4 in the hemizygous condition. The btl-Gal4 construct used has UAS-actin-GFP sequences on the same chromosome. This allowed GFP imaging of the tracheal system (shown in the (g) and (h) lower panels). Air in the tracheae produces light refraction making the outlines of the DTs and lateral connective tracheal branches visible in control larvae. Fluid in the tracheae renders the tracheae almost invisible. For btl-Gal4 > lov RNAi (h), although grossly morphologically normal (compare (g) and (h) lower panels) the entire tracheal system is fluid-filled, whereas for lov91Y -Gal4 > lov RNAi (d), the entire system is air-filled. In cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae (b), region Tr10 of the DTs is always fluid-filled and is noticeably shorter. In this larva, Tr9 is also fluid-filled in one of the DTs. lov91Y -Gal4 /lov def larvae (f) show a different phenotype: the tracheae are air-filled but overall larval growth is inhibited producing convoluted tracheae in some larvae. LC = lateral connectives, SP = spiracles. Scale bars = 200 μm.

The larvae that proved exceptional to this correlation of behavioral/developmental defects with tracheal fluid accumulation were lov91Y-Gal4/lov def larvae. In addition to being a lov Gal4 enhancer trap insertion, lov91Y is a lov mutation in its own right, initially identified for the defective gravity responses it produces [6]. Further analysis of the lov91Y-Gal4/lov def larval phenotype is discussed below.

Are the tracheal lov knockdown behavioral defects a consequence of hypoxia?

Fluid-filling of the tracheae will inevitably limit oxygen exchange in the larva suggesting that both the behavioral and growth effects of lov tracheal knockdown reflect responses to hypoxia. The aberrant behaviors of lov tracheal knockdown larvae reported here are strikingly similar to a larval response to hypoxia described previously. Normal larvae feeding on piles of yeast paste burrow into their food headfirst, but keep their posterior spiracles outside the food, exposed to the air. Wingrove and O’Farrell [13] established that in hypoxic conditions, third instar larvae abandon this feeding position and rapidly move out of their food. To establish whether third instar cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae will leave the interior of a yeast pile like hypoxic larvae, we placed them under mounds of yeast paste and monitored their behavior as compared to controls. As shown in Fig 6, whereas control (cut(ue)-Gal4 /+) larvae stayed in the food, cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae came out of the yeast pile in a manner comparable to that of wild type larvae subjected to 1% oxygen (Fig 6A—compare Fig 1F, Wingrove and O’Farrell 332 [13]).

Fig 6. Failure to burrow and tunnel mimic hypoxia-induced behaviors.

(a) cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae or control larvae were buried under a pile of yeast paste and the number of larvae that crawled out of the pile was monitored over time. Control larvae stayed in the yeast but the experimental larvae left the paste in numbers and at a rate comparable to findings for hypoxic larvae [13], n = 200 in batches of 10 larvae. Error bars = +/- SEM. (b) Wandering wild-type Canton-S larvae, tunneling in plates as used for the tunneling assay, were subjected to an atmosphere of N2 gas and the number of larvae that left their tunnels and moved to the agarose surface was monitored over time. N = 120 in batches of 10 larvae. Error bars = +/-SEM.

To determine whether failure to tunnel is also a response to hypoxia, we subjected wild type larvae that were actively tunneling in the agarose substratum to very low oxygen levels by flushing the Petri plates with nitrogen gas. As shown in Fig 6B, ~80% of the larvae quickly moved out of their tunnels onto the agarose surface under these conditions. Thus in wild type larvae, absence of tunneling is a behavioral response to lack of oxygen.

In wild type larvae, these hypoxia-induced behaviors are rapidly initiated by sensory neurons some of which contain atypical soluble guanylyl cyclases that act as oxygen sensors (reviewed in [24]). However, interpreting the behavioral defects of cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae as purely neuronal responses to hypoxia is complicated by the recognition that long- lasting hypoxia depresses metabolism and produces both growth and behavioral defects [25, 26]. cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae that survive to wandering stage and fail to tunnel are noticeably smaller than controls (Fig 5B) and are sluggish. btl-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae are even more strongly affected: they show very little growth (Fig 5H) and at death are comparable to larvae exposed to 3.5% oxygen during days two and three after hatching (see Fig 1, Reference [26]). Thus, an alternative explanation for failed burrowing and tunneling in cut(ue)-Gal4>lov RNAi is that these defects are indirect responses to prolonged hypoxia and reflect the fact that the larvae are too physiologically challenged to burrow and tunnel.

A comparison of the locomotor activity of lov91Y-Gal4 /lov def larvae with that of cut-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae provides insight on this point (Fig 7). In the hemizygous condition, lov91Y-Gal4 produces effects on growth and survival to adulthood comparable to those seen for cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi (compare in Figs 3B and 4B and Fig 5B with 5F). But the tracheae remain open and air-filled in lov91Y-Gal4 /lov def larvae (Fig 5F) so they are unlikely to be hypoxic. Thus, in contrast to the cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae, the mutant phenotypes of these larvae probably result from neural defects caused by the lov91Y insertion (see Discussion) rather than from loss of lov expression in the tracheae. Upon testing, lov91Y-Gal4 /lov def larvae proved more compromised in terms of locomotion than cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae: although forward locomotion rates are comparable and low for the two genotypes, lov91Y-Gal4 hemizygous larvae are also hampered by spontaneous backward motion (Fig 7A). Nevertheless lov91Y-Gal4 /lov def larvae burrow into their food (S2 Fig) and show tunneling (Fig 2I), quantitated as ~18% that of the averaged control value (Fig 5A), whereas ~50% of cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae do not burrow (S2 Fig) and their failure to tunnel is absolute (Fig 3A). This comparison suggests that the burrowing /tunneling defects in cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi are not due to indirect effects on growth and locomotion but rather are a direct neural response to hypoxia.

Fig 7. Locomotor defects of lov91Y-Gal4/lov def larvae compared to cut(ue)-Gal4>lov RNAi larvae and lov91Y-Gal4/lov def larval growth defects.

(a) Larval locomotion was analyzed as described in Material and Methods, for forward and backward strides, and head turns. N = >50 for all genotypes. P values, Student’s t-test, black *** = P 377 <0.0001, black * = P < 0.01, red ** = P < 0.001, red * = P < 0.01, all compared to cut-Gal4/+. lov91Y -Gal4/lov def larvae are more compromised than cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae. (b) Larval length measurements. At least 20 larvae for each genotype were imaged as described in Material and Methods. The images were processed with Adobe Photoshop and NIH Image J to measure the body length. P value, Student’s t-test, * = P <0.001 compared to +/lov def.

To identify direct evidence of hypoxia in lov tracheal knockdown larvae we examined the expression of genes known to be induced by low oxygen in larval life. Responses to hypoxia show strong developmental regulation in Drosophila. In particular, late embryos and early larvae show very limited changes in gene expression in hypoxia, with no increase in transcripts for the canonical indicator of hypoxia—lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) [27]. This probably reflects the fact that embryos and early larvae rely heavily on aerobic glycolysis (lactate production in the presence of oxygen), with concomitant upregulation of LDH [28]. In contrast, wandering third instar larvae show significant transcriptional responses to hypoxia, with LDH showing the greatest upregulation of all genes examined [27]. Given that btl-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae die before this stage, we thus focused on determining whether wandering cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae/early prepupae show hypoxia-induced transcriptional changes.

We used Semi-Q RT-PCR to probe for transcripts from the four genes shown previously to undergo the greatest hypoxia-induced upregulation at this developmental stage [27]; these are CG10160, the gene for LDH (also known as ImpL3 in Drosophila); CG11652, the gene for dDPH1, a component of diphthamide synthesis; CG4608, the gene for the FGF receptor, Branchless, and CG31543, the gene for Fatiga, the prolyl hydroxylase that regulates levels of the key hypoxia-induced transcription factor HIF-α (Sima in Drosophila) [27]. No consistent increase in expression for fatiga and dDPH1 was detected, with branchless transcripts showing a minor but consistent upregulation relative to control (data not shown). In contrast, transcripts for LDH were consistently upregulated about two fold (2.3 +/- 0.5) in cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae as compared to controls (Fig 8). Given the key role of this enzyme in anaerobic respiration, we conclude that cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae are hypoxic.

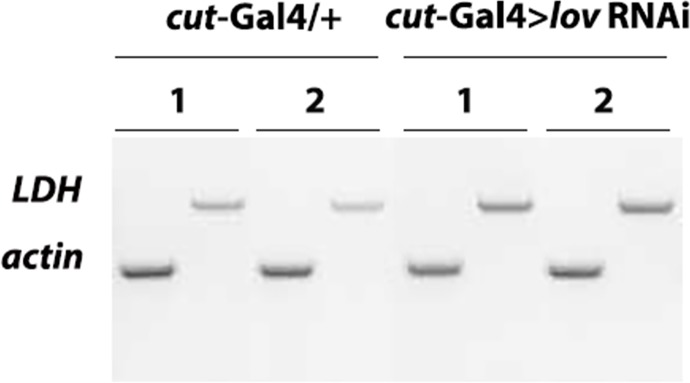

Fig 8. LDH expression is up-regulated in cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae.

Late wandering third instar larvae were collected for RNA extraction. Semi-Q RT-PCR was used for transcript analysis. LDH and actin PCR products for each RNA sample were run in parallel in separate gel lanes. 1 and 2 indicate RT-PCR products from two independent RNA preparations. Four RNA preparations total gave comparable results. For quantitation of LDH upregulation in cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae, band intensities for the LDH and actin PCR products were quantitated with NIH image J and used to calculate LDH/actin (L/a) ratios for control and experimental (cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi) samples. The fold increase in LDH expression in the experimental samples was then calculated as the average value for L/a experimental/L/a control.

The lov91Y-Gal4 /lov def phenotype

We found that lov91Y-Gal4 hemizygous larvae are phenotypically distinct from larvae with tracheal knockdown of lov, both in terms of behavior and morphology. As discussed above, behaviorally they differ in that they display spontaneous backward locomotion and some tunneling activity and morphologically they have air-filled tracheae. In addition, although, like tracheal lov RNAi larvae, they are smaller than controls (Fig 7B), their reduced size shows evidence of a disconnect between the growth of the tracheae and the body at large. Thus, 50% of the lov91Y-Gal4 hemizygous larvae examined had highly convoluted tracheae indicating tracheal growth in excess of overall growth (Fig 5F). In contrast, mild tracheal convolution was seen in only 14% of the control larvae (data not shown). Several aspects of the lov91Y-Gal4 hemizygous phenotype are similar to those detected previously for mutation lov47 [6]. The mutation deletes DNA close to the PGawB insertion site in lov91Y resulting in loss of Lov expression in many neural phenotypes. We address these similarities in the Discussion.

lov knockdown in the tracheae inhibits growth and polyploidization of the tracheal epithelial cells in larval life

We found only minor structural defects in the late embryonic/early larval tracheal system of btl-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae (data not shown). Further, the tracheae in btl-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae inflate normally just before hatching. Thus the tracheal leakiness detected here appears to reflect a role for lov during tracheal growth and development in larval life.

One cause of larval tracheal fluid-filling is loss of the lipid water barrier within the posterior spiracles. A simple assay in which a dye is added to semi-liquid food makes spiracle water entry easily detectable [29]. Using this assay we saw no dye within the spiracles in cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae (data not shown), even though there are fluid-filled tracheal regions very close to the spiracles in these larvae.

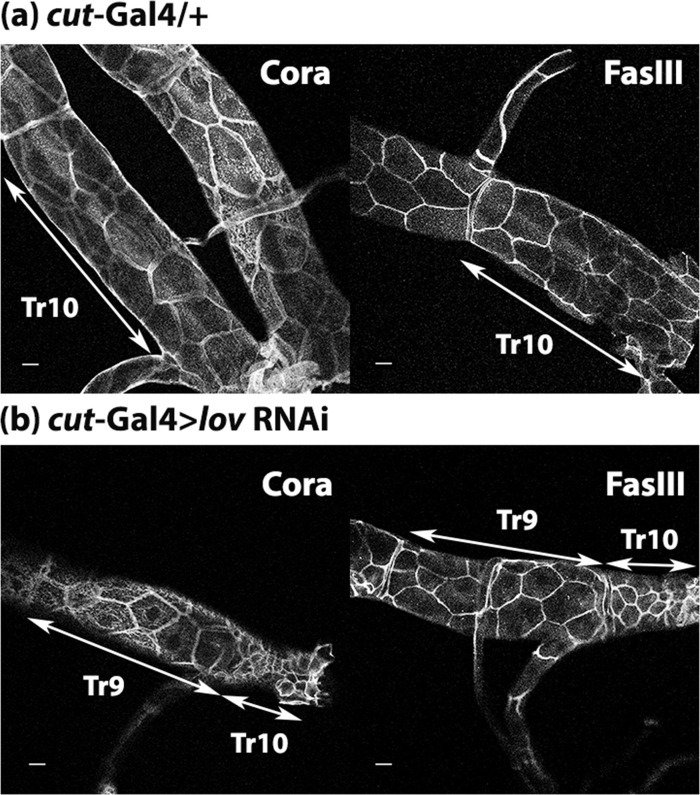

To look for defects in the tracheae proper, we took advantage of the extremely regional expression of Gal4 seen with the cut(ue)-Gal4 driver. Under this driver, adjacent sections of the tracheal trunks showing weak (Tr9) or strong (Tr10) lov RNAi knockdown can be compared. We therefore developed a protocol to dissect out the dorsal trunks from late stage larvae to examine these tracheal regions in cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi and control animals. Given that the septate junctions (equivalent to vertebrate tight junctions) provide the barrier to fluid passage through the tracheal epithelial cell layer [30], we first investigated the expression of two key septate junction proteins (Coracle (Cora), and Fas III). These proteins were both present at high levels on the cell membranes of Tr9 and Tr10 in both cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi and control larvae. At the light microscope level, no differences in localization of these proteins between control and experimental tissues was detected (Fig 9).

Fig 9. cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi larval tracheae show normal immunostaining for septate junction constituents.

Confocal images of (a) cut(ue)-Gal4/+ and (b) cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi tracheae stained with either Coracle (Cora) or Fas III antibodies. Tracheae were dissected from third instar larvae as described in Material and Methods. Staining at the plasma membranes for both proteins is similar in control and lov knockdown tracheae but the cells of Tr10 are much smaller in the cut(ue)Gal4 > lov RNAi genotype. Scale bars = 20 μm.

However, in performing these immunolocalization studies, an unexpected finding emerged. As shown in Fig 1B and 1G, the cut(ue)-Gal4 driver produces a very specific pattern of Gal4 expression in the DTs, with low levels in Tr9, high levels in Tr10, and even higher levels in the bridge and the extreme terminal sections of the DTs adjacent to the spiracles. We found that, in cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi, the size of the DT epithelial cells decreases dramatically in the region of high Gal4 expression. Tr9 cells appear somewhat smaller than in control larvae and Tr10 cells are considerably reduced compared to Tr9 cells (Fig 9). In wild type larvae, cells posterior to the bridge are already noticeably smaller than in the rest of the DTs (data not shown) and in the cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae these cells were so small and disorganized that they were usually no longer attached to the spiracles. A break in the continuity of the DTs that would allow hemolymph entry was therefore present at this position.

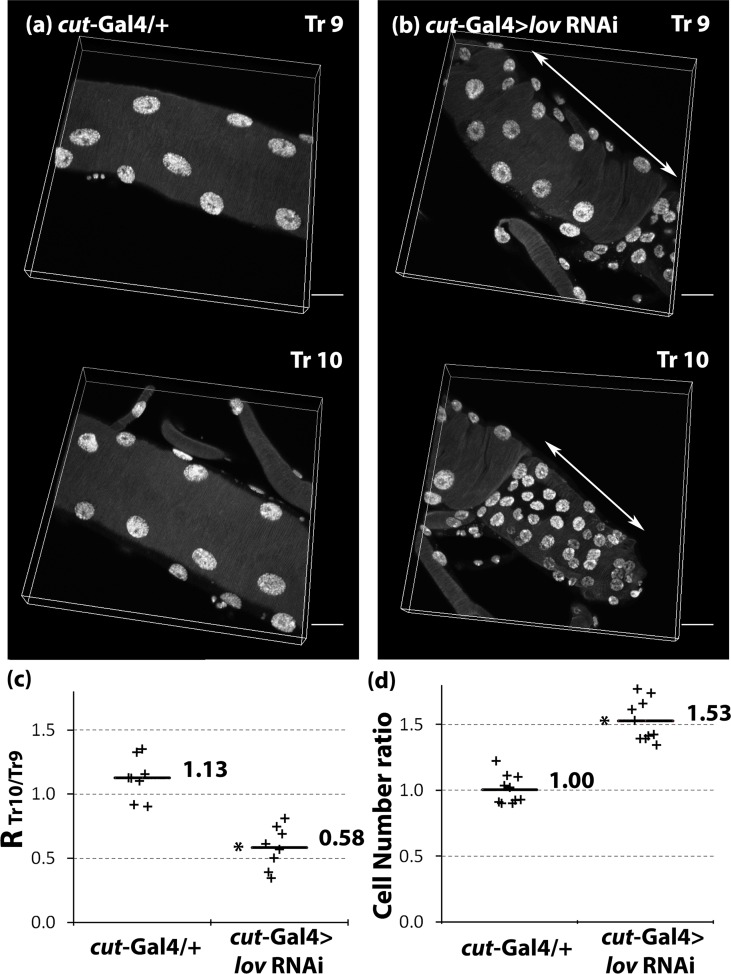

Although the cells in Tr10 were strongly affected by the lov knockdown, in most dissected DTs the Tr10 metamere was sufficiently intact to allow further analysis. DAPI nuclear staining revealed that the nuclei in Tr10 cells were noticeably smaller than those in Tr9 and there appeared to be more cells in this region than in the equivalent control region (Fig 10). Quantitation of the average ratio of Tr10/Tr9 nuclear fluorescence for cells in cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi and cut(ue)-Gal4 /+ larvae established that, whereas in controls, the nuclear DNA content of cells in Tr9 and Tr10 is similar, in lov knockdown larvae the DNA content of Tr10 cells is about half that of Tr9 cells (Fig 10). We also calculated the average Tr10/Tr9 ratio of nuclear numbers for control and cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi tracheae as an indication of the number of cells in each segment. Whereas the cell numbers for Tr9 and Tr10 are comparable in controls, in the lov knockdown tracheae, we quantitated a 50% increase in cell number for Tr10 over Tr9 (Fig 10). This quantitation probably underestimates the increase in cell number in Tr10. In lov knockdown DTs, the region posterior to Tr10 containing the smallest cells is almost always damaged such that its boundary with Tr10 is obscured. We therefore delineated the region we called Tr10 conservatively and thus probably excluded some Tr10 cells from our calculations.

Fig 10. In cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi tracheae, cells of DT Tr10 are smaller, more numerous, and show decreased DNA content compared to adjacent cells in DT Tr9.

DAPI stained nuclei in confocal sections of DT metameres Tr9 and Tr10 from (a) cut(ue)-Gal4 /+ and (b) cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi third instar tracheae. (c) After DAPI quantitation (see Material and Methods) an RTr10/Tr9 value was calculated for all control or lov knockdown tracheae examined. RTr10/Tr9 = average of DAPI intensity per nucleus (Tr10)/average of DAPI intensity per nucleus (Tr9)). Horizontal bars show average RTr10/Tr9 values. The average RTr10/Tr9 value for cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi is approximately half that of cut(ue)-Gal4 /+ larvae. (d) The cell number ratios for control and lov knockdown tracheae in Tr9 and Tr10. Cell number ratios = cell numbers in Tr10/cell numbers in Tr9 and were calculated as described in Material and Methods. An increase in cell number of ~50% is indicated in Tr10 compared to Tr9 for cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi, as compared to control. Each + represents data collected from an individual larva. Scale bars = 20 μm. P value, Student’s t-test, * = P <0.00002 for cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi compared to cut(ue)-Gal4 /+.

Discussion

The link between lov tracheal expression and burrowing and tunneling behaviors

The failed food burrowing and substratum tunneling identified by this work led us to discover a new role for lov in the post-embryonic growth of the tracheal system. Although our expectation was that these behaviors originated in neural functions for lov, we found that they arise indirectly from a breach in tracheal integrity induced upon lowering Lov levels in the tracheae. This breach leads to tracheal fluid-filling, hypoxia, and finally, hypoxia-activated behaviors. These hypoxia-activated behaviors cannot originate in Lov-expressing neurons since the key tracheal driver used here, cut(ue)-Gal4, does not express in any neural elements. Rather, we hypothesize that the guanylyl cyclase-expressing neurons identified by the Morton laboratory as oxygen-sensing neurons [31] are the sensory elements that trigger the hypoxia-induced behaviors we have characterized here. Surprisingly, the role of lov that is disrupted to initiate these behaviors involves growth and polyploidization of the tracheal epithelial cells.

How might this decreased growth lead to loss of the barrier properties of the tracheal cells? As part of the 200-fold increase in weight during larval life [32], the larva body increases eight-fold in length [33]. Thus, suppression of tracheal cell growth will stretch the tracheae, a mechanical stress that could lead to physical rupture, allowing fluid entry. Our observations of the tracheal regions showing lov knockdown under the cut(ue)-Gal4 driver support this hypothesis. The DTs were frequently broken in the region posterior to Tr10 where the lov knockdown levels were highest. This region, and the adjacent Tr10, were always fluid-filled in the lov knockdown larvae.

This explanation for the origin of the tracheal damage assumes that loss of growth and endopolyploidy induced by lov knockdown precedes the tracheal damage and fluid-filling also produced by lov RNAi. As an alternative it could be argued that an unidentified initial defect causes tracheal leakage and then the presence of fluid in the tracheae inhibits tracheal growth. For example, despite our findings from light microscopy, we could propose that the septate junctions are not functional in lov knockdown, leading to fluid entry and subsequent growth inhibition. Preliminary experiments (data not shown), in which weaker lov knockdown in the tracheae was achieved by countering cut(ue)-induced Gal4 activity with leaky Gal80 expression, make this possibility unlikely. In these cut(ue)-Gal4/Gal80 > lov RNAi larvae, Tr10 growth is inhibited but there is no fluid accumulation in the tracheae.

Systemic hypoxia in cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae is limited

Our data indicate that the amount of tissue hypoxia in cut(ue)-Gal4>lov RNAi larvae is low when compared to that detected in comparable stage larvae exposed to 4% oxygen for six hours [27]. Although we found a consistent detectable increase in LDH gene expression, this increase is small compared the 14-fold upregulation of LDH RNA reported for systemic exposure to 4% oxygen. For three further genes that show substantial upregulation in 4% oxygen (dDPH, 11x increase, fatiga, 8x increase, branchless, 11x increase) we found small, in some cases inconsistent, changes in our cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae.

Given the highly regional fluid-filling of the tracheae produced with the cut(ue) driver, we interpret this finding to mean that tissue hypoxia is mostly limited to regions surrounding the affected tracheal sections, that is, Tr9, Tr10 and the bridge region. The Morton laboratory has shown that the terminal sensory cones located on abdominal segments A8 and A9 contain neurons expressing oxygen-sensing guanylyl cyclases and are major oxygen sensing organs for the larva [24, 31, 34]. These sense organs are very close to the affected tracheal segments in cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae and we propose they undergo sufficient oxygen deprivation in these mutant animals to activate the behavioral responses characterized here.

The effects of lov on the growth and polyploidization of the tracheae

The morphogenesis of the Drosophila larval tracheal system during embryogenesis requires no growth by mitosis and cell division (for reviews see [35–37]). Instead, individual sections of the tracheae arise from clusters of epidermal cells that migrate inwards and undergo remarkable shape changes to produce a series of repeating, complex, branched structures in the segments of the developing embryo. Late in embryogenesis, so-called fusion cells at the tips of particular branches of each structure fuse these individual elements to give rise to the final continuous tubular system.

Subsequently, as for most of the larval tissues, the large increase in size of the tracheal system in larval life is accomplished by endoreplicative growth, that is, multiple rounds of DNA replication without nuclear or cytoplasmic division. This growth produces large cells each containing a single large polyploid nucleus. The precise point at which this endoreplicative growth is initiated is not known, but previous work indicates that most of the larval tissues have undergone at least one round of endoreplication prior to larval hatching [38].

Our examination of DT cells that have experienced lov knockdown since late in embryogenesis reveals that these cells are smaller, more numerous and reduced in DNA content. Comparisons to nuclei/cells in the imaginal discs, which remain diploid in larval life, make it clear however that the lov knockdown DT cells have undergone some endoreplicative growth. These findings raise the possibility that lov has a role in the initial commitment to endoreplication at the very end of embryogenesis, when lov expression in the DTs is initiated, and that when lov is depleted, this transition is delayed and instead some growth by mitotic divisions occurs. As discussed below, the cells in Tr2 of the DTs only grow by regular cell divisions, demonstrating that mitotic growth can occur in the larval DTs.

Our quantitation was based on comparing nuclear parameters for Tr9 to those of Tr10 within the same DT. This was done to avoid introducing additional variation by comparing Tr10 regions from control and experimental animals. Although this quantitation defines the aspects of tracheal cell growth that are affected by lov knockdown, it is likely that it underestimates the effects of a complete loss of lov function on these parameters. One factor causing an under-estimation of cell number increase (conservative definition of the posterior Tr10 boundary) is described above. Other factors that probably lessen the effects detected include the activity of the cut(ue) enhancer in Tr9 as well as in Tr10 (see Fig 1) and incomplete lov knockdown by the RNAi construct used. Complete loss of lov activity in these cells might thus produce a population that fails to initiate endoreplicative growth entirely.

The molecular mechanisms regulating endopolyploidy within the tracheal system have not been investigated. However, in other endopolyploid tissues, the Insulin pathway has been identified as coordinating endopolyploidy with the nutritional status of the larvae [39] and the Notch pathway has been shown to coordinate endopolyploidy with tissue morphogenesis in the ovarian follicles [40].

The cut(ue) enhancer and regional specialization of the tracheae

The Gal4 expression generated by the cut(ue) enhancer is strikingly limited, immediately suggesting a role for cut in regional specialization of individual DT metameres. It is noteworthy that the region of highest activity of this enhancer is the region closest to the spiracles, posterior to the “bridge” structure, where polyploidization of the tracheal epithelial cells is detectably lower than in metameres Tr9 and Tr10 (see above). Regional transcriptional specialization in the tracheal system has already been demonstrated [41]. Further, the Tr2 regions of the DTs, which have the specialized role of generating the dorsal air sacs during pupal development, are distinctly different from other metameres in that their cells remain mitotically active and do not undergo polyploidization during larval life [42]. Studies of the tracheoblast cells associated with Tr4 and Tr5 have identified subpopulations of cells with different levels of mitotic activity differentiation, and polyploidization that are coordinated by a gradient of cut expression across each tracheoblast cell cluster [17, 43]. A precedent for cut regulation of regional specialization within the tracheal system therefore exits. However, other enhancers associated with the cut gene are known to regulate cut expression in the spiracles and tracheae [20, 44] and thus the aggregate expression pattern for cut in the DTs may differ considerably from that produced by the cut(ue) enhancer alone. Quantitation of Cut tracheal protein expression is needed to resolve this issue.

Neural and non-neural roles for lov in behavior

Unlike larvae with lov tracheal knockdown, lov91Y-Gal4 hemizygous larvae show no indications of tracheal permeability but display backward movement, failure of systemic growth and poor survival to adulthood. These phenotypes are similar to those of lov47, a deletion mutation generated from the lov91Y chromosome in which 1.4 kb of DNA upstream of the lov91Y PGawB transposon insertion site are missing [6]. In lov47 mutant embryos, Lov expression in many elements of the developing larval nervous system is lost, suggesting that the phenotypes generated are neural in origin [6]. It seems likely therefore that the lov91Y-Gal4 hemizygous larval phenotypes, like those of lov47, are also neural in origin.

The lov91Y PGawB insertion site is ~ 500 bp upstream of the start site for transcripts B and D of the lov gene [6]. Our previous studies with lov47 indicated that the region around this site contains a regulatory element(s) controlling the expression of transcript D in neural tissues. The Gal4 expression pattern for the lov91Y PGawB insertion described here reveals the presence of additional regulatory sequences in this region that control lov expression in the larval tracheae. The tracheal phenotypes identified here demonstrate the effects of specific knockdown of this component of lov expression in larval life. However, the lov47and lov91Y -Gal4 phenotypes probably derive from direct disruption of neural regulatory elements within this same DNA region and thus affect neural roles for the gene in larvae.

The immediate stimulus for a behavioral response is typically neural. From the middle stages of embryogenesis until hatching, lov is expressed strongly and almost exclusively in the developing nervous system [6] and all the behavioral phenotypes we have previously identified for lov are probably neural in origin. In contrast, these current studies define an additional route by which lov may activate behavioral responses and in general, they underscore the fact that genes can influence behavior in multiple, often indirect, ways.

Material and Methods

Drosophila stocks

The following stocks were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC); BL27327 (w-; cut-Gal4.B - here called cut(ue)-Gal4); BL8807 (w*; btl-Gal4, UASp-Act5C-GFP/CyO, PlacZ); BL4961(Df (2R) K10 b pr Bl c (here called lov deficiency chromosome, lov def) /SM1); the CyO-GFP balancers from stocks BL5702 (Sco/CyO, hsp-70-Gal4,UAS- GFP) and BL6662 (w-; Gla/ CyO twi-Gal,UAS-2xEGFP) were used to prepare lov deficiency chromosome/CyO-GFP stocks. lov RNAi stocks used were as follows; #10739, from the Vienna Drosophila Resource Center; #JF02205 (Valium 10 construct) and #HMS01126 (Valium 20 construct) from the TRiP Project at Harvard Medical School. Canton-S was used as the wild type (+) stock for these studies. lov91Y was identified in a previous screen [5]. Stocks were used as received from suppliers.

Burrowing and tunneling assay

Petri plates (10 cm) with a layer (3–4 mm) of 2% agarose were generated and 10 newly hatched larvae of a given genotype were placed in a central well containing a standard amount (0.8 gms) of yeast paste (7 gms yeast, 10 ml water). At least 50 larvae for each genotype were examined. Growth, burrowing and tunneling behavior, and survival were observed daily through to adulthood. Once adults had emerged, plates were washed extensively with water to remove debris and dried for 1–2 days. Images of the tunneling patterns on the plates were then taken with a Biorad GelDoc Universal Hood II system, using a black background. Under these conditions the tunnels appeared as white strips against the dark background. Tunneling was then quantitated from negatives of these images by calculating the total number of dark pixels in tunnels per plate using NIH image J. An initial round of studies used agarose plates without mold inhibitor. After noting that mold growth in the tunnels increased the pixel count on Image J, 0.25% methyl p-hydroxybenzoate (Nipagen) was included in all plates. Comparisons of tunneling activity were only performed between sets of plates that were either all + Nipagen or—Nipagen.

Tracheal imaging and analysis

Embryos from the appropriate crosses were collected on grape plates for four hours and after hatching, larvae were raised on mounds of yeast paste on grape plates at 22oC. For crosses involving btl-Gal4, UAS-Actin-GFP/CyO, GFP larvae were selected using a Leica MX FluoIII fluorescence microscope. For imaging, larvae were immobilized either with ether vapor before mounting in 70% glycerol or by heating for a few seconds on a 70oC hot plate [26] after mounting. Microscopes used for imaging were as follows; bright field and fluorescence images in Fig 1 (A-D, F, G) and Fig 5 (G, H)—Zeiss Axioplan2; bright field images in Fig 5 (A-D)—Zeiss Axioimager 2; bright field images in Fig 1(E) and Fig 5 (E, F)—Zeiss Axioskop. For quantitation of tracheal defects (Fig 5), larvae were imaged from Day1 after hatching until the day before pupation or death, as determined form the studies in Figs 3 and 4. At least 10 larvae were imaged for each genotype and fluid-filling of the tracheae was quantitated from stored image sets.

Larval Locomotion Assay

Embryos from appropriate crosses were collected on grape plates for four hours. The midpoint of this four hours was used as the Average Egg Lay time (AEL). Larvae were fed on mounds of yeast paste on grape plates at 22oC and assayed 90–92 hours after AEL. A lov def /CyO twi-2x GFP stock was used for crosses to generate hemizygous larvae and non-GFP larvae were selected at 72 hours AEL then reared separately to 90–92 hours AEL. For assay, each larva was transferred to a clean 2% agarose plate, given one minute to acclimatize and then forward strides, backward strides and head turns were scored over a one minute period under a dissecting microscope. Assays were performed at 18oC, >50 larvae of each genotype were analyzed. Student’s t-test was used to compare all other genotypes to the cut(ue)-Gal4/+ control.

Semi-Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was isolated from embryos or larvae using Trizol lysis as previously [45]. RNA was reverse transcribed with Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and a random hexamer mix (New England Biolabs). PCR (30 cycles) at appropriate annealing temperatures was used to generate DNA fragments specific for each targeted gene. Agarose gel electrophoresis and GelRed Nucleic Acid Stain (Phenix) were used to detect DNA fragments. Actin57B, which is abundantly expressed in larvae, and ribosomal protein gene rp49 were used as control genes for standardizing expression. Primers used were:

actin forward: 5’ TTCCAAGCCGTACACACCGTAACT 3’

actin reverse: 5’ TCATCACCGACGTACGAGTCCTTCT 3’

rp49 forward: 5' TACAGGCCCAAGATCGTGAA 3'

rp49 reverse: 5' CACGTTGTGCACCAGGAACT 3'

lactate dehydrogenase set 1 forward: 5’ CATCCTTGTCAATGCCATGTTC 3’

lactate dehydrogenase set 1 reverse: 5’ TGCTTATGGTGTCCAATCCC 3’

set 2 forward: 5' CTGAAGAACCCCCAGATCAC 3'

set 2 reverse: 5' GCAAAATGGTATCGGGACTG 3'

branchless forward: 5' TTGCCTGTATCTCTGCATGG 3'

branchless reverse: 5' TCGTGTAGGTGCTCAGCTTG 3'

fatiga forward: 5' GACAAGATCCGAGGCGATAA 3'

fatiga reverse: 5' CGCTCCCTGATGTGGTAGTT 3'

dDPH1 forward: 5' TGCCAGAGACAACGAAGATG 3'

dDPH1 reverse: 5' GCCTTGTCTTCCGAGTGTTC 3’

Tracheal dissection

Larvae were dissected in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) with 1mM EDTA, following the protocol described by Ramachandran and Budnik [46]. The internal organs except the tracheal system were cleaned out as much as possible. Posterior spiracles were cut off without destroying the last segment of the tracheal system. After dissection, the entire tracheal system was still attached to the cuticle. Preparations were then fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde for 30 min. After washing with PBS, tracheae were ready for further treatment.

Immunostaining

Fixed dissected larval tracheae were blocked in BBXN (PBS, 0.3% Triton-X 100, 0.1% BSA, 5% goat serum). Primary antibodies used were i) guinea pig anti-Lov, prepared in two guinea pigs (Cocalico Biologicals, Inc) against the Lov protein fragment used previously to generate rabbit and guinea pig Lov antisera [6, 47], and ii) mouse anti-Coracle and anti-Fas III both from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank. Anti-Lov was used at a 1:50 dilution in BBXN, followed by biotin-labeled secondary antibody (Vector Labs, 1:500 dilution in BBXN), streptavidin-horse radish peroxidase (Thermo scientific), and metal-enhanced 3, 3’- Diaminobenzidine (DAB) (Thermo scientific) detection. Anti-Fas III and anti-Coracle were used at 1:10 or 1:5 dilution in BBXN) and detected with goat anti-mouse IgG labelled with Alexa Fluor 594 nm (BD BioSciences, 1:500 dilution in BBXN). Tracheae were detached from the larval cuticle before mounting. Images were taken with a Zeiss Axioskop or a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope.

Polyploidy and cell number measurements

Dissected tracheae were treated sequentially with 0.1% Triton in PBS for 10 min, 0.1M ammonium chloride in PBS for 10 min, 50 mg/μl RNAse A (Thermo scientific) in PBS for 1 hour and finally DAPI (4', 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, 0.01 mg/ml in PBS, Invitrogen) for 5 min. Tracheae were then detached from the cuticle for mounting. To quantitate DAPI intensity, image series were taken via a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope with a 40x oil immersion objective. Nikon NIS-Element C software was then used to build 3D images of nuclei and quantitate DAPI intensity for each selected nucleus. An average of six nuclei were analyzed in each tracheal segment, and tracheae from eight individual larvae were analyzed per genotype. To quantitate cell numbers in Tr9 and Tr10 of the tracheal system, a Zeiss Axioplan2 was used, and 10 individual tracheal pairs were analyzed for each genotype.

Supporting Information

All the lov RNAi lines were driven by elav-Gal4. Embryos (12–16 hrs after egg laying) were collected for RNA extraction. Semi-Q RT-PCR was used for transcript quantification. lov and actin PCR products for each RNA sample were run in parallel in separate agarose gel lanes. RNA preparations from two sets of embryos gave identical results. See Material and Methods for RNAi line sources.

(TIF)

Larvae were placed in tunneling assays one day after hatching as described in Material and Methods. (a) for both cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi and btl-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae, failure to burrow (larvae outside the food) is seen but this is associated with greater larval death (as opposed to transition to pupation) for btl-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae. (b) In the lov hemizygous condition, cut(ue)-Gal4/lov def > lov RNAi larvae outside the food die in greater numbers rather than pupating. Larvae were assayed in batches of 10. At least five batches per genotype were examined. Error bars = +/- SEM.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank our Rice colleagues Peter Lwigale and Dan Wagner for use of their microscopes. We thank David Morton, Jon Harrison, Rob Ward, and Julian Martinez-Agosto for helpful conversations. We are grateful to Niki Sankoorikkal for generating the data in Fig 7A. Our colleague at Baylor College of Medicine, Herman Dierick, provided valuable comments on the manuscript. The services of the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, the Harvard TRiP facility, the Vienna Drosophila Resource Center, and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank are gratefully acknowledged. We thank Rice undergraduates Rami Dibbs, Philip Frasse, Tamer Ghanayem, Radhika Mohan, Joyce Saborio and Peter Yun and Ye Yuan, a visiting intern from China, for their input and help with these experiments.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

Rice University provided a teaching fellowship for FZ.

References

- 1.Rodriguez L, Sokolowski MB, Shore JS. Habitat selection by Drosophila melanogaster larvae. J Evol Biol. 1992;5: 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carton Y, Sokolowski M. Parasitization of embedded and nonembedded Drosophila melanogaster (Diptera: Drosophilidae) pupae by the parasitoid Pachycrepoideus vindemniae (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae). J Insect Behav. 1994;7: 129–131. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong JL, Sokolowski MB, Kent CF. Prepupation behavior in Drosophila: embedding. Behav Genet. 1985;15: 155–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Narasimha S, Kolly S, Sokolowski MB, Kawecki TJ, Vijendravarma RK. Prepupal building behavior in Drosophila melanogaster and its evolution under resource and time constraints. PLOS ONE. 2015;10: e0117280 10.1371/journal.pone.0117280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armstrong JD, Texada MJ, Munjaal R, Baker DA, Beckingham KM. Gravitaxis in Drosophila melanogaster: a forward genetic screen. G2B. 2006;5: 222–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bjorum SM, Simonette RA, Alanis R Jr, Wang JE, Lewis BM, Trejo MH, et al. The Drosophila BTB domain protein Jim Lovell has roles in multiple larval and adult behaviors. PLOS ONE. 2013;8: e61270 10.1371/journal.pone.0061270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albagli O, Dhordain P, Deweindt C, Lecocq G, Leprince D. The BTB/POZ domain: a new protein-protein interaction motif common to DNA- and actin-binding proteins. Cell Growth Diffn. 1995;6: 1193–1198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brand A, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 1993;118: 401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bodmer R, Barbel S, Sheperd S, Jack JW, Jan LY, Jan YN. Transformation of sensory organs by mutations of the cut locus of D. melanogaster. Cell. 1987;51: 293–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jack J, Dorsett D, Delotto Y, Liu S. Expression of the cut locus in the Drosophila wing margin is required for cell type specification and is regulated by a distant enhancer. Development. 1991;113: 735–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jack J, DeLotto Y. Structure and regulation of a complex locus: the cut gene of Drosophila. Genetics. 1995;139: 1689–1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo Y, Livne-Bar I, Zhou L, Boulianne GL. Drosophila presenilin is required for neuronal differentiation and affects notch subcellular localization and signaling. J Neurosci. 1999;19: 8435–8442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wingrove JA, O'Farrell PH. Nitric oxide contributes to behavioral, cellular, and developmental responses to low oxygen in Drosophila. Cell. 1999;98: 105–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Venken KJ, Schulze KL, Haelterman NA, Pan H, He Y, Evans-Holm M, et al. MiMIC: a highly versatile transposon insertion resource for engineering Drosophila melanogaster genes. Nature Methods. 2011;8: 737–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pitsouli C, Perrimon N. Embryonic multipotent progenitors remodel the Drosophila airways during metamorphosis. Development. 2010;137: 3615–2624. 10.1242/dev.056408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Attrill H, Falls K, Goodman JL, Millburn GH, Antonazzo G, Rey AJ, et al. FlyBase: establishing a Gene Group resource for Drosophila melanogaster. Nucl Acids Res. 2016;44(D1): D786–D792. 10.1093/nar/gkv1046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pitsouli C, Perrimon N. The homeobox transcription factor cut coordinates patterning and growth during Drosophila airway remodeling. Science Signaling. 2013;6: ra12 10.1126/scisignal.2003424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wieschaus E, Nusslein-Volhard C, Jurgens G. Mutations affecting the pattern of the larval cuticle in Drosophila melanogaster. Wil Roux Arch Dev Biol. 1984;193: 296–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blochlinger K, Jan LY, Jan YN. Postembryonic patterns of expression of cut, a locus regulating sensory organ identity in Drosophila. Development. 1993;117:441–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bourbon HM, Gonzy-Treboul G, Peronnet F, Alin MF, Ardourel C, Benassayag C, et al. A P-insertion screen identifying novel X-linked essential genes in Drosophila. Mech Dev. 2002;110:7 1–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zelzer E, Shilo BZ. Cell fate choices in Drosophila tracheal morphogenesis. BioEssays. 2000; 22: 219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takaesu NT, Johnson AN, Newfeld SJ. Posterior spiracle specific GAL4 lines: new reagents for developmental biology and respiratory physiology. Genesis. 2002;34: 16–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu L, Johnson WA, Welsh MJ. Drosophila DEG/ENaC pickpocket genes are expressed in the tracheal system, where they may be involved in liquid clearance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100: 2128–2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morton DB. Behavioral responses to hypoxia and hyperoxia in Drosophila larvae. Fly. 2011;5: 119–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harrison JF, Haddad GG. Effects of oxygen on growth and size: synthesis of molecular, organismal, and evolutionary studies with Drosophila melanogaster. Annu Rev Physiol. 2011;73: 95–113. 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong DM, Shen Z, Owyang KE, Martinez-Agosto JA. Insulin- and warts-dependent regulation of tracheal plasticity modulates systemic larval growth during hypoxia in Drosophila melanogaster. PLOS ONE. 2014;9: e115297 10.1371/journal.pone.0115297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y, Padmanabha D, Gentile LB, Dumur CI, Beckstead RB, Baker KD. HIF- and non- HIF-regulated hypoxic responses require the estrogen-related receptor in Drosophila melanogaster. PLOS Genetics. 2013;9: e1003230 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tennessen JM, Bertagnolli NM, Evans J, Sieber MH, Cox J, Thummel CS. Coordinated metabolic transitions during Drosophila embryogenesis and the onset of aerobic glycolysis. G3 (Bethesda, Md). 2014;4: 839–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parvy JP, Napal L, Rubin T, Poidevin M, Perrin L, Wicker-Thomas C, et al. Drosophila melanogaster Acetyl-CoA-carboxylase sustains a fatty acid-dependent remote signal to waterproof the respiratory system. PLOS Genetics. 2012;8: e1002925 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tepass U, Tanentzapf G, Ward R, Fehon R. Epithelial cell polarity and cell junctions in Drosophila. Annu Rev Genet. 2001;35: 747–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vermehren-Schmaedick A, Ainsley JA, Johnson WA, Davies SA, Morton DB. Behavioral responses to hypoxia in Drosophila larvae are mediated by atypical soluble guanylyl cyclases. Genetics. 2010;186: 183–196. 10.1534/genetics.110.118166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Church RB, Robertson FW. Biochemical analysis of genetic differences in the growth of Drosophila. Genet Res. 1966;7: 383–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glasheen BM, Robbins RM, Piette C, Beitel GJ, Page-McCaw A. A matrix metalloproteinase mediates airway remodeling in Drosophila. Dev Biol. 2010;344: 772–783. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.05.504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Langlais KK, Stewart JA, Morton DB. Preliminary characterization of two atypical soluble guanylyl cyclases in the central and peripheral nervous system of Drosophila melanogaster. J Exp Biology. 2004;207: 2323–2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Affolter M, Shilo BZ. Genetic control of branching morphogenesis during Drosophila tracheal development. Current Op Cell Biol. 2000;12: 731–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghabrial A, Luschnig S, Metzstein MM, Krasnow MA. Branching morphogenesis of the Drosophila tracheal system. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19: 623–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uv A, Cantera R, Samakovlis C. Drosophila tracheal morphogenesis: intricate cellular solutions to basic plumbing problems. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13: 301–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith AV, Orr-Weaver TL. The regulation of the cell cycle during Drosophila embryogenesis: the transition to polyteny. Development. 1991;112: 997–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Britton JS, Lockwood WK, Li L, Cohen SM, Edgar BA. Drosophila's insulin/PI3-kinase pathway coordinates cellular metabolism with nutritional conditions. Developmental cell. 2002;2: 239–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun J, Deng WM. Notch-dependent downregulation of the homeodomain gene cut is required for the mitotic cycle/endocycle switch and cell differentiation in Drosophila follicle cells. Development. 2005;132: 4299–4308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Faisal MN, Hoffmann J, El-Kholy S, Kallsen K, Wagner C, Bruchhaus I, et al. Transcriptional regionalization of the fruit fly's airway epithelium. PLOS ONE. 2014;9: e102534 10.1371/journal.pone.0102534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guha A, Lin L, Kornberg TB. Organ renewal and cell divisions by differentiated cells in Drosophila. Proc Nal Acad Sci USA 2008;105: 10832–10836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pitsouli C, Perrimon N. Embryonic multipotent progenitors remodel the Drosophila airways during metamorphosis. Development. 2010;137: 3615–3624. 10.1242/dev.056408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nepveu A. Role of the multifunctional CDP/Cut/Cux homeodomain transcription factor in regulating differentiation, cell growth and development. Gene. 2001;270: 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bogart K, Andrews J. Extraction of total RNA from Drosophila. Center for Genomics and Bioinformatics. 2006;CGB Technical Report 2006–10:doi:10.2506/cgbtr-200610.

- 46.Ramachandran P, Budnik V. Immunocytochemical staining of Drosophila larval body- wall muscles. Cold Spring Harbor Protocols. 2010;pdb.prot5470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bjorum SM. A lov story: a role for jim lovell in Drosophila neural development and fertility. PhD thesis, Rice University. 2010: 60–61.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

All the lov RNAi lines were driven by elav-Gal4. Embryos (12–16 hrs after egg laying) were collected for RNA extraction. Semi-Q RT-PCR was used for transcript quantification. lov and actin PCR products for each RNA sample were run in parallel in separate agarose gel lanes. RNA preparations from two sets of embryos gave identical results. See Material and Methods for RNAi line sources.

(TIF)

Larvae were placed in tunneling assays one day after hatching as described in Material and Methods. (a) for both cut(ue)-Gal4 > lov RNAi and btl-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae, failure to burrow (larvae outside the food) is seen but this is associated with greater larval death (as opposed to transition to pupation) for btl-Gal4 > lov RNAi larvae. (b) In the lov hemizygous condition, cut(ue)-Gal4/lov def > lov RNAi larvae outside the food die in greater numbers rather than pupating. Larvae were assayed in batches of 10. At least five batches per genotype were examined. Error bars = +/- SEM.

(TIF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.