Abstract

Spirocyclic hypervalent iodine(III) ylides have proven to be synthetically versatile precursors for efficient radiolabelling of a diverse range of non-activated (hetero)arenes, highly functionalised small molecules, building blocks and radiopharmaceuticals from [18F]fluoride ion. Herein, we report the implementation of these reactions onto a continuous-flow microfluidic platform, thereby offering an alterative and automated synthetic procedure of a radiopharmaceutical, 3-[18F]fluoro-5-[(pyridin-3-yl)ethynyl]benzonitrile ([18F]FPEB) and a routinely used building block for click-radiochemistry, 4-[18F]fluorobenzyl azide. This new protocol was applied to the synthesis of [18F]FPEB (radiochemical conversion (RCC) = 68 ± 5%) and 4-[18F]fluorobenzyl azide (RCC=68 ± 5%; isolated radiochemical yield = 24±0%). We anticipate that the high throughput microfluidic platform will accelerate the discovery and applications of 18F-labelled building blocks and labelled compounds prepared by iodonium ylide precursors as well as the production of radiotracers for preclinical imaging studies.

1. Introduction

Positron Emission Tomography (PET) is an established molecular imaging technique that has applications in clinical diagnosis and drug development, especially in combination with anatomical imaging techniques including computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Fluorine-18 (18F) [1] is widely regarded as the foremost radionuclide for PET due to the significant use of 19F in drug design [2], as well as a favourable decay profile (97% β+ decay to 18O). Furthermore, its relatively long half-life (t½ = 109.8 min) enables imaging timeframes and multi-centre trials [3], which are not possible with other common radionuclides, such as carbon-11 (11C [t½ = 20.3 min]). Radiometals that are used for PET imaging purposes can have longer half-lives (e.g, 64Cu [t½ = 12.7 h] and 89Zr [t½ = 78.4 h]), however these are not suitable for small molecule drugs without change to their parent structures, as they require high-affinity chelators for complexation.

Continuous-flow microfluidic technology can offer significant advantages for the synthesis of PET radiotracers, including increased reproducibility, faster reaction kinetics and rapid reaction optimisation [4]. There have been over 50 reported syntheses of labelled compounds for PET that exploit the advantages of continuous-flow microfluidics [5]. Recently, continuous-flow microfluidics was used for the preparation of [18F]FPEB [6], [18F]T807 [7], and [18F]FMISO [8] for human use, whilst [18F]Fallypride [9] has comparably been prepared using a micro-reactor.

We recently reported a novel procedure for the 18F-fluorination of hypervalent iodonium(III) ylides to give 18F-arenes from 18F-fluoride [10], that provided efficient regiospecific labelling for a diverse scope of non-activated functionalised (hetero)arenes. These include electron-donating motifs, which have typically been difficult to label with preceding hypervalent iodine(III) mechanisms, as well as highly functionalised molecules and PET radiopharmaceuticals. This approach has recently been extended to the automated production of 3-[18F]fluoro-5-[(pyridin-3-yl)ethynyl]benzonitrile ([18F]FPEB) in a good radiochemical yield (15 – 25%, formulated and ready for injection, n=3) and validated for human use, utilising a commercial radiosynthesis module [11].

The goal of the work presented herein was to demonstrate a translation of our spirocyclic iodonium(III) ylide methodology onto a continuous-flow microfluidic platform and utilize the high throughput advantages held by this technology over both manual and other automated protocols. This work aims to enable rapid radiochemistry optimisation and synthesis of labelled compounds for preclinical research.

As proof of concept, our goals were: 1) to confirm that the iodonium ylide precursors can be suitably translated to a commercial continuous flow reactor system with a model substrate; 2) to synthesize and isolate 18F-fluorobenzyl azide, a building block for high throughput click chemistry and 3) to synthesize a radiopharmaceutical, with [18F]FPEB as a model compound, which was previously a challenge to synthesize for preclinical or clinical work.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1 Synthesis of model 18F-labelled substrates via iodonium ylide precursors and continuous flow microfluidics

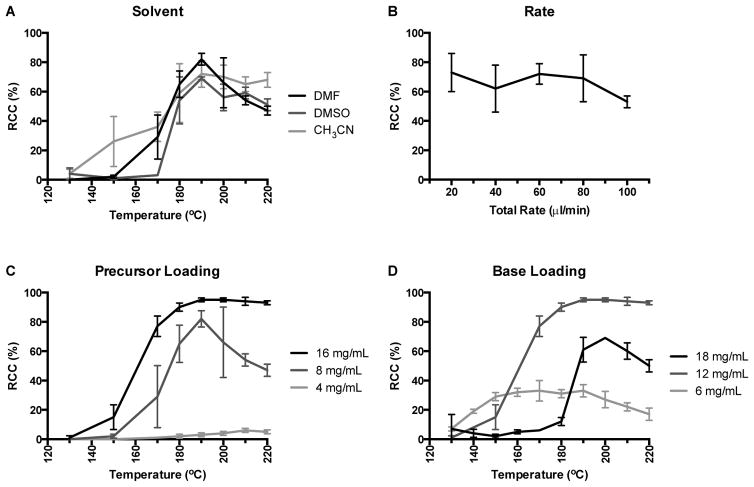

A commercial continuous-flow microfluidic platform (NanoTek®; Advion, Inc.) [12] was utilised for this study. A model biphenyl iodonium ylide precursor was explored for initial proof-of-concept and reaction optimisation using tetraethylammonium [18F]fluoride ([18F]TEAF) as the 18F-fluoride source, formed by the elution of 18F-fluoride from an anion exchange cartridge with a solution of tetraethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB). The precursor, 6,10-dioxaspiro[4.5]decane-7,9-dion-[1,1′-biphenyl-4-iodonium] ylide (1) was reacted with [18F]TEAF to form 4-[18F]fluorobiphenyl (2), and was chosen for this study to allow for a direct comparison of incorporation of 18F-fluoride based on our previous manual synthesis [10]. The initial conditions, translated from our previous approach (8mg/mL 1, 12 mg/mL [18F]TEAF/TEAB, DMF, RCC = 85%) [10], were subjected to a temperature range (130 – 220°C) using a 4m (32μL) reactor, into which the [18F]TEAF/TEAB (Pump 3 [P3]) and substrate solutions (Pump 1 [P1]) were introduced in a 1:1 (P1:P3) ratio. This immediately showed that an automated approach could match the RCCs from a manual approach and consequently a more exhaustive optimisation of the reaction conditions was rapidly performed. A comparison of DMF, DMSO and CH3CN (Figure 1A) showed DMF to be the preferred solvent, though intriguingly CH3CN performed better at T ≥ 200°C, at which a drop in conversion was observed in all other solvents. In comparison, CH3CN was dismissed early in the manual methodology as it had led to relatively low conversion with this substrate and reaction condition (9±8%, n=3) [10] when compared with both DMF and DMSO. We attributed the lower yield to the lower boiling point of CH3CN as the limiting factor.

Figure 1.

Optimisation plots for radiolabelling of 4-[18F]fluorobiphenyl (2). Conditions (n=2, 4m reactor): A: 8mg/mL 1, 12mg/mL [18F]TEAF/TEAB, 60μL/min; B: 8mg/mL 1, 12mg/mL [18F]TEAF/TEAB, DMF, 190°C; C: 12mg/mL [18F]TEAF/TEAB, DMF, 60μL/min; D: 16mg/mL 1, DMF, 60μL/min.. Incorporation yield as radiochemical conversion (RCC) and product identity were determined by radioTLC and radioHPLC, respectively

A study of five different flow rates through the reactor (20 – 100μL/min) showed that there was no significant change in the conversion, with a slight increase at slower rates being annulled by the increased time for the reaction and respective decay of activity (Figure 1B). Both the precursor loading and base ([18F]TEAF/TEAB)) loading were optimised consecutively using DMF as the solvent. It was found that increasing the precursor loading to 16mg/mL improved the incorporation of fluoride into 2 across the temperature range and the drop in conversion, which had been seen when T > 190°C, was no longer observed (Figure 1C).

Decreasing the loading of [18F]TEAF/TEAB in the system increased the RCC at lower temperature, although a reduction in conversion was observed once the temperature exceeded 160°C. Increasing the base loading decreased the conversions across the temperature range 140°C to 220°C (Figure 1D). The effect of the base loading with a series of other ylides has been observed by us and a mechanistic study will be published elsewhere, Final optimised conditions for the radiofluorination of 1 (16mg/mL 1, 12mg/mL [18F]TEAF/TEAB, DMF, 60μL/min, P1:P3 1:1, 4m (32μL) reactor) gave excellent incorporation of 18F-fluoride (95±1%, T=200°C, n=4) (Scheme 1), and offers an improvement on the RCC established by the manual procedure (85%) [10].

Scheme 1.

Radiosynthesis of 4-[18F]fluorobiphenyl (2).

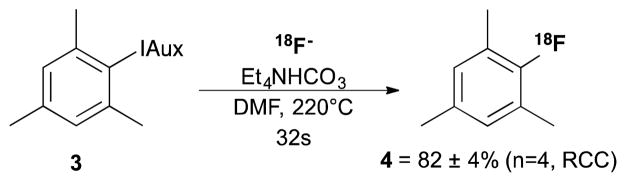

As the radiochemical conversion was almost quantitative, we subjected 6,10-dioxaspiro[4.5]decane-7,9-dion-[1,3,5-trimethylbenzene-2-iodonium] ylide (3) to these conditions (16mg/mL 3, 12mg/mL [18F]TEAF/TEAB, DMF, 60 μL/min) (Scheme 2), in an attempt to quantify the degree to which the application on microfluidics could affect the conversion of these reactions. This substrate gave a conversion of 82±4% (T=220°C, n=4) to 2-[18F]fluoro-1,3,5-trimethylbenzene (4), which is almost double that obtained by our previously published method (45±13%, n=3) [10].

Scheme 2.

Radiosynthesis of 2-[18F]fluoro-1,3,5-trimethylbenzene (4).

The use of these model substrates has shown that the application of a microfluidic reactor has the capability for significantly improving the conversion of spirocyclic iodonium ylides to 18F-arenes and justified our next efforts to apply this technology to clinically relevant labelled compounds.

2.2 Synthesis of 4-[18F]Fluorobenzyl azide

The first target molecule chosen for evaluation of this microfluidic protocol was 4-[18F]fluorobenzyl azide (6), which is used in a ‘building-block’ approach to radiopharmaceuticals which cannot be directly fluorinated. This is achieved via fast, metal-free “click” reactions with strained alkynes, such as for Bombesin [13], a GRP-receptor-specific 14 amino acid neuropeptide. Previous procedures for the synthesis of 6 have followed several methodologies; via a stepwise procedure (4-steps, 75 min, RCY=34% [decay corrected]) [14], nucleophilic aromatic substitution of a nitro group [13] or via microfluidic approach using diaryliodonium salt precursors which gave a RCC of 51% with 3% of the labelled anisole by-product [15]. The stepwise procedure was automated using solid supports to improve the RCY to up to 60% over a 40 minute synthesis time [16]. We have previously reported a manual one-step radiosynthesis using an iodonium ylide precursor (6) with RCY of 25±10% (n=3) [10] via solid phase extraction (SPE) isolation techniques, utilising this spirocyclic iodonium(III) ylide chemistry

Initial reactions, using the optimised conditions for the reaction of 1, on 6,10-dioxaspiro[4.5]decane-7,9-dion-[1-(azidomethyl)benzene-4-iodonium] ylide (5) gave moderate conversion to 6 (31±1%, T=200°C, n=3), and a temperature dependence similar to that seen for radiofluorination of 1 (Figure 2A). However, unlike in the synthesis of 2, it was found that there was a significant increase in the yield when the flow rate was dropped from 60 μL/min to 20 μL/min (44%, T=200°C, n=1) (Figure 2B). This is likely attributed to the increase in residence time in the reactor (32 s to 96 s), though this decrease in total flow rate consequently increases the time taken per reaction. In an attempt to enable an increase in residence time, whilst reducing the obligatory increase in run time, the reactor was changed from 4 metres in length (32 μL volume) to 8 metres (64 μL volume). This allowed for an increased reaction residence time (32 s to 64 s), while reducing the increase in time to end of synthesis.

Figure 2.

Temperature variation optimisation for the radiofluorination of 4-[18F]fluorobenzyl azide (6). Conditions (n=1, 4m reactor; n=3, 8m reactor): A 16mg/mL 5, 12mg/mL [18F]TEAF/TEAB, DMF, 60μL/min; B 1. 16mg/mL 5, 12mg/mL [18F]TEAF/TEAB, DMF, 200°C, 4m reactor.

The adoption of the 8 metre reactor increased the incorporation across the temperature range investigated (Figure 2A), with the optimum temperature being found to be 210°C (68 ± 5%, n=3), which represents an increase in conversion of 17% under a shorter residence time than previously published microfluidic techniques [15]. These conditions were successfully taken forward and combined with SPE isolation to give a non-decay corrected RCY=24 ± 0.4% (n=3, relative to the amount of [18F]fluoride obtained at the end of bombardment) in a total synthesis time of 60 minutes from target unload to assay of final product vial, with a radiochemical purity (RCP) of >95% (Scheme 3). This procedure was fully automated from the azeotropic drying of the 18F-fluoride to the final collection vial.

Scheme 3.

One-step radiosynthesis and isolation of 4-[18F]fluorobenzyl azide (6).

2.3 Synthesis of 3-[18F]Fluoro-5-[(pyridin-3-yl)ethynyl]benzonitrile ([18F]FPEB)

Our final efforts focused on the synthesis of a radiopharmaceutical targeting the metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype type 5 (mGluR5), a glutamatergic neural receptor implicated in a number of central nervous system disorders including chronic neurodegenerative disorders, such as Huntington’s and Parkinson’s disease [17]. 3-[18F]Fluoro-5-[(pyridin-3-yl)ethynyl]benzonitrile ([18F]FPEB, 8) is a mGluR5 antagonist that has been successfully applied in preclinical [18,19] and clinical PET research studies [20,21].

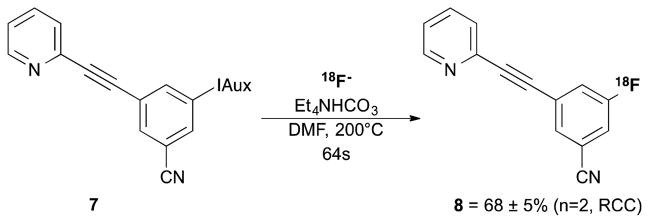

Original routes to [18F]FPEB required high temperatures and several radiochemical impurities have been identified during production, yet only low RCYs were recovered (1–5%) [22,23]. The presence of an electron-withdrawing nitrile group meta- to the fluorination centre leads to a displacement of traditional leaving groups (Cl or NO2) being disfavoured. Our group has published two routes to [18F]FPEB previously. The first applied the NanoTek® to facilitate a SNAr displacement of a nitro group, which gave low radiochemical yields (2%) [6]. More recently we have extended this iodonium(III) ylide methodology [11] to give good RCC under a manual procedure (49±6%, n=3) and consequent adaption for automation on a commercial radiofluorination platform led to [18F]FPEB formulated for injection in an isolated uncorrected RCY of 20±5% (n=3). Hydrolysis of the nitrile group lead to the formation of a radiolabelled by-product and its suppression could increase radiochemical conversions. It was therefore envisaged that a combination of these two approaches (iodonium ylide chemistry in conjunction with continuous flow microfluidics) would lead to a higher yielding process with potentially less impurities to produce this important radiopharmaceutical.

Following the discovery of the benefits of using the 8m reactor on the azide system, this was immediately applied to the radiofluorination of 3-((7,9-dioxo-6,10-dioxaspiro[4.5]decan-8-ylidene)-λ3-iodanyl)-5-(pyridine-2-ylethynyl)benzonitrile (7) (Figure 3). Due to hydrolysis of the nitrile being known, especially at higher temperatures, the lower temperature range limit was decreased to 100°C. However, no hydrolysis was observed by radio-HPLC during the optimisation, even at 220°C, with the sole radioproduct identified as 8. It was found that there is a relatively narrow temperature in which an excellent RCC can be achieved (68±5%, T=200°C, n=2), with relatively rapid decrease in conversion observed with variation from this point (Scheme 4). To our knowledge and in our hands, this conversion is superior to all other known routes to [18F]FPEB. We envision that continuous flow microfluidics in conjunction with iodonium ylide based precursors will be widely useful for preparing preclinical doses of [18F]FPEB from relatively small amounts of 18F-fluoride and should prove useful for clinical translation.

Figure 3.

Temperature variation optimisation for the radiofluorination of 4-[18F]FPEB (8). Conditions (n=3, 8m reactor): 16mg/mL 7, 12mg/mL [18F]TEAF/TEAB, DMF, 60μL/min.

Scheme 4.

Radiosynthesis of [18F]FPEB (8).

3. Conclusion

This work has demonstrated the capability and application of an automated continuous-flow microfluidic platform to the 18F-fluorination of spirocyclic iodonium(III) ylides, which can improve incorporation of 18F-fluoride, and reduce reaction time as well as reagent use. The benefit of using of the iodonium ylide methodology allows the labeling of arenes displaying electron-withdrawing groups, including trifluoromethyl, halide, nitro and ester substituents at the meta (non-activated) positions. However, a few exceptions for this methodology are expected, such as those which cannot tolerate the oxidation conditions. These include precursors with unprotected hydroxy groups, amines and carboxylic acids. The benefits of the use of microfluidics include the rapid optimization using minimal reagents, low activity, over a wide range of temperatures and residence times. Typically, there is an increase in radiochemical yield using microfluidics due to the improved mixing and improved heat transfer capabilities. As proof of concept, two important 18F-labelled compounds, 4-[18F]fluorobenzyl azide and [18F]FPEB, were radiolabelled via this technology and should have widespread implications in radiotracer production.

4. Experimental

Substrates (1, 3, 5 and 7) and the reference compounds ([19F]2, [19F]4, [19F]6 and [19F]8) were synthesised as previously published [10,11]. Full details of radiochemical synthesis of compounds 2, 4, 6 and 8, including NanoTek® schematic and automation macros, can be found in the ESI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by the MRC (SC), Advion (SC & NV) and Ground Fluor Pharmaceuticals (NV). VG holds a Royal Society Wolfson Research Merit Award (2013–2018). We thank Dr. Benjamin H. Rotstein and Dr. Nickeisha Stephenson for selected substrate synthesis and helpful discussions. We thank Dr Jack A. Correia, David F. Lee, Jr. and Tim Beaudoin and the Massachusetts General Hospital PET Core facility for 18F-fluoride production.

References

- 1.Cai LS, Lu SY, Pike VW. Eur J Org Chem. 2008;17:2853–2873. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Menaa F, Menaa B, Sharts ON. J Mol Pharm Org Process Res. 2013;1:104. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller PW, Long NJ, Vilar R, Gee AD. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:8998–9033. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rensch C, Jackson A, Lindner S, Salvamoser R, Samper V, Riese S, Bartenstein P, Wangler C, Wangler B. Molecules. 2013;18:7930–7956. doi: 10.3390/molecules18077930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pascali G, Watts P, Salvadori PA. Nucl Med Biol. 2013;40:776–787. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liang S, Yokell D, Jackson R, Rice P, Callahan R, Johnson K, Alagille D, Tamagnan G, Collier T, Vasdev N. Med Chem Commun. 2014;5:432–435. doi: 10.1039/C3MD00335C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liang S, Yokell D, Normandin M, Rice P, Jackson R, Shoup T, Brady T, El Fakhri G, Collier T, Vasdev N. Molecular Imaging. 2014;13:1–5. doi: 10.2310/7290.2014.00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng M, Collier L, Bois F, Kelada O, Hammond K, Ropchan J, Akula M, Carlson D, Kabalka G, Huang Y. Nucl Med Biol. 2015;42:578–584. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lebedev A, Miraghaie R, Kotta K, Ball C, Zhang J, Buchsbaum M, Kolb H, Elizarov A. Lab Chip. 2013;13:136–145. doi: 10.1039/c2lc40853h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rotstein B, Stephenson N, Vasdev N, Liang S. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4365. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stephenson NA, Holland JP, Kassenbrock A, Yokell DL, Livni E, Liang SH, Vasdev N. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:489–492. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.151332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pascali G, Matesic L, Collier T, Wyatt N, Fraser B, Pham T, Salvadori P, Greguric I. Nat Protoc. 2014;9:2017–2029. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell-Verduyn L, Mirfeizi L, Schoonen A, Dierckx R, Elsinga P, Feringa B. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:11117–11120. doi: 10.1002/anie.201105547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thonon D, Kech C, Paris J, Lemaire C, Luxen A. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009;20:817–823. doi: 10.1021/bc800544p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chun J, Pike V. Eur J Org Chem. 2012;24:4541–4547. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201200695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lemaire C, Libert L, Plenevaux A, Aerts J, Franci X, Luxen A. J Fluorine Chem. 2012;138:48–55. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bordi F, Ugolini A. Prog Neurobiol. 1999;59:55–79. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00095-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rook JM, Tantawy MN, Ansari MS, Felts AS, Stauffer SR, Emmitte KA, Kessler RM, Niswender CM, Daniels JS, Jones CK, Lindsley CW, Conn PJ. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:755–765. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J, Tueckmantel W, Zhu A, Pellegrino D, Brownell A. Synapse. 2007;61:951–961. doi: 10.1002/syn.20445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sullivan J, Lim K, Labaree D, Lin S, McCarthy T, Seibyl J, Tamagnan G, Huang Y, Carson R, Ding Y, Morris E. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:532–541. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong D, Waterhouse R, Kuwabara H, Kim J, Brasic J, Chamroonrat W, Stabins M, Holt D, Dannals R, Hamill T, Mozley P. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:388–396. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.107995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamill T, Krause S, Ryan C, Bonnefous C, Govek S, Seiders T, Cosford N, Roppe J, Kamenecka T, Patel S, Gibson R, Sanabria S, Riffel K, Eng W, King C, Yang X, Green M, O’Malley S, Hargreaves R, Burns H. Synapse. 2005;56:205–216. doi: 10.1002/syn.20147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim K, Labaree D, Li S, Huang Y. Appl Radiat Isot. 2014;94:349–354. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.