Abstract

PURPOSE

While technology is a major driver of many of society’s comforts, conveniences, and advances, it has been responsible, in a significant way, for engineering regular physical activity and a number of other positive health behaviors out of people’s daily lives. A key question concerns how to harness information and communication technologies (ICT) to bring about positive changes in the health promotion field. One such approach involves community-engaged “citizen science,” in which local residents leverage the potential of ICT to foster data-driven consensus-building and mobilization efforts that advance physical activity at the individual, social, built environment, and policy levels.

METHOD

The history of citizen science in the research arena is briefly described and an evidence-based method that embeds citizen science in a multi-level, multi-sectoral community-based participatory research framework for physical activity promotion is presented.

RESULTS

Several examples of this citizen science-driven community engagement framework for promoting active lifestyles, called “Our Voice”, are discussed, including pilot projects from diverse communities in the U.S. as well as internationally.

CONCLUSIONS

The opportunities and challenges involved in leveraging citizen science activities as part of a broader population approach to promoting regular physical activity are explored. The strategic engagement of citizen scientists from socio-demographically diverse communities across the globe as both assessment as well as change agents provides a promising, potentially low-cost and scalable strategy for creating more active, healthful, and equitable neighborhoods and communities worldwide.

Keywords: physical activity promotion, citizen science, population health, active living, community, health equity

Background

While technology is a major driver of many of society’s comforts, conveniences, and advances, there are substantial data to suggest that it has also contributed to engineering regular physical activity and a number of other positive health behaviors out of people’s daily lives (24, 36). As a result, higher-income nations as well as a growing number of low- to middle-income countries worldwide are facing unprecedented levels of physical inactivity (24, 52). For example, it has been estimated that approximately one-third of U.S. adults are inactive (i.e., no light, moderate, or more vigorous intensity physical activity of at least 10 minutes in duration) (37). Inactivity levels have contributed substantively to the persistence of high chronic disease rates in industrialized countries, and to their increasing prevalence in developing nations (30, 51, 52). Research suggests that physical inactivity accounts for nearly 1 in 10 premature U.S. deaths (9).

The disease risk associated with physical inactivity is not spread evenly across the population, tending to cluster among communities that lack the economic, educational, and infrastructure-related resources to support active and healthful lifestyles (37). For example, built environment research across a number of different countries and cultures has indicated that low-income, under-resourced communities often have fewer local environmental assets in support of regular physical activity and a greater number of barriers to active living compared to higher-income communities (11). More impoverished communities also may have fewer opportunities to acquire or readily engage with the cutting-edge information and communication technologies (ICT) that can support or help to sustain more physically active lifestyles (46).

To date, much of the physical activity promotion literature has targeted putative drivers of physical activity behavior primarily at the individual level or individual plus local contextual levels of impact. Much has been learned through controlled experimental research on individual-level behavioral and social factors that can drive choices to be active or not. There is also a significant evidence base in support of behavioral strategies to increase regular physical activity across diverse populations (26)--sometimes for extended time periods (12). Unfortunately, national funding agencies have been less willing to support efforts to systematically translate and disseminate this substantial body of evidence in ways that would significantly impact population health and reduce health disparities. While many such interventions require significant human resources, a growing amount of ICT research in the field suggests that the behavioral strategies that have been found to be effective in face-to-face contexts can be successfully delivered through a range of remote communication channels (e.g., interactive voice response systems; web-based programs; smartphone applications [apps]; virtual advisors, etc.) (16, 27, 28). Such findings notwithstanding, few ICT-based health promotion programs available to the public take full advantage of behavioral theory or have been evaluated rigorously across extended time periods (28, 34). Those programs and apps that do exist often focus primarily on individual behaviors and on the well-educated, technology-savvy, English-speaking subgroups of the population who often need them least (28). As such, these interventions do little to change the underlying social, environmental, and policy-related factors that constitute the major drivers of physical inactivity, poor health, and health inequalities in the U.S. and elsewhere (26).

A Data-Driven Approach to Transforming Communities for Active Living

The environments in which people live, work, and play significantly affect their daily physical activity levels along with other health-promoting behaviors (40). Multi-sectoral approaches aimed at addressing local environments and policies that impact a community’s physical activity levels while taking into account person-environment interactions are strongly needed. While “community” can be understood in a variety of ways, according to geography, population, health factors, or other unifying factors, for the purposes of this paper, the boundaries of community are defined by residents as well as locally-based partnering organizations, i.e., their constituents and target service groups.

Citizen science offers an innovative, multi-layered approach to increasing physical activity and other healthy behaviors in both more affluent as well as under-resourced and marginalized communities. This strategy empowers residents to collect diagnostic information about their community environment, prioritize areas of concern, and engage in cross-sector collaboration to generate practical and impactful solutions. An example is a neighborhood watch group that conducts a survey of their residents to identify the greatest needs for safety and then uses this information to communicate with local authorities to get those needs met. Among the problems currently faced by health promotion science that such citizen science may help ameliorate are a) a dearth of multi-sectoral, multi-level, or cross-generational approaches that can expand impact and promote sustainability of positive health behaviors; b) a lack of research that incorporates the perspectives of the target audience it ultimately aims to serve; c) time- and resource-intensive funding processes and research protocols that often delay community translation and use; d) “one-size-fits-all” approaches that do not take into account the diversity of communities (e.g., socioeconomic differences between communities), differences between residents within communities or neighborhoods, or the specific challenges and opportunities within these locales; e) insufficient reach into underserved populations (e.g., low-income, culturally diverse, non-English speaking); and f) lack of support for intervention translation and dissemination activities.

In a complementary fashion, among the advantages that citizen science can bring to the health promotion intervention endeavor are a) increased relevance of scientific inquiry for community members; b) early resident “buy in” to the scientific process that in turn can facilitate participant enrollment, retention, intervention delivery and quality control, dissemination, and scale-up; and c) the ability to leverage more diverse linkages across population groups, sectors of influence, and communication methods that can aid more rapid diffusion and sustainability of the programs and interventions of interest (33). During the community engagement process, residents trained as “citizen scientists” can play a variety of roles, including collaborators in the formulation of relevant research questions; data collectors; interventionists; monitors relating to ethical standards; data compilers; and contributors to data interpretation as well as translation and dissemination activities. Citizen scientists can also communicate their experiences and successes using impactful personal narratives that grab the attention of decision-makers and the public, successfully compelling action in a way that straight “facts and figures” approaches often cannot (19, 25, 45).

History of citizen science activities

Citizen science can be defined broadly as involving members of the public who work with professional scientists to advance a research project (39). It capitalizes on people’s innate sense of curiosity about the world around them in addition to a wide range of other motives (e.g., learning, fun, societal contribution) (39). Citizen science has been applied for centuries to expand the abilities and resources of researchers to collect information needed to advance scientific knowledge. For the most part, these activities can be described as falling into two general categories (as summarized in Table 1): citizen science “for the people,” which typically has involved voluntary donation of biological specimens and other activities to advance biomedical research (17, 20); and citizen science “with the people,” in which residents assist in observational data collection (3). Some of the most enduring citizen science contributions to date have been made in the latter category, within the biology, meteorology, and conservation fields (48). For example, by working “with the people” and entrusting critical data collection to lay people living within environments of interest, researchers have gained new insights into bird and wildlife migration, earthquakes, weather, and other natural phenomena (31, 35).

TABLE 1.

Conceptualization of a Citizen Science Continuum.

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| “For the People” | Residents contribute to biomedical research by donating biological specimens, participating in genomic medicine, or crowdsourcing applications |

| “With the People” | Residents document and report on natural phenomena such as wildlife migration, earthquakes and weather |

| “By the People” | Residents document their physical and social environments, code and synthesize the data, and use their findings to advocate for change. |

An equally compelling area in which discourse on citizen science has exploded is in biomedical knowledge advancement. Among the relevant activities in which community members are becoming increasingly integrated are “partnership models” between patient organizations and biomedical researchers (38), public participation in genomic medicine (23), and web-based crowdsourcing applications (4).

While “for the people” and “with the people” citizen science approaches have involved the public in different methods of data acquisition for the purposes of scientific inquiry, few have systematically utilized the unique perspectives of residents to gain a fuller understanding of the phenomena under inquiry as well as to drive positive solutions to documented challenges. “By the people” citizen science takes the engagement process further by partnering with residents as potentially powerful agents of change. In contrast to the other citizen science approaches, the “by the people” approach aims to more fully engage and empower residents not only as data gatherers, but also as active collaborators in modifying their local environments and fostering neighborhoods more conducive to active living and healthy lifestyles.

Our Voice: Combining Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) with “By the People” Citizen Science to increase physical activity at the population level

In order to systematize data-gathering by diverse groups of residents, the Stanford Healthy Aging Research and Technology Solutions Laboratory at Stanford University School of Medicine initiated the early development of the Healthy Neighborhood Discovery Tool (7) (described below), which has been refined in collaboration with public health leaders, scientists, and organizations from Mexico, Colombia, Israel, Chile, and the U.S. This simple mobile device-based ICT application literally gives residents who have traditionally lacked pathways to local decision-making a “voice” and a means of telling their stories in ways that command attention and induce action (25).

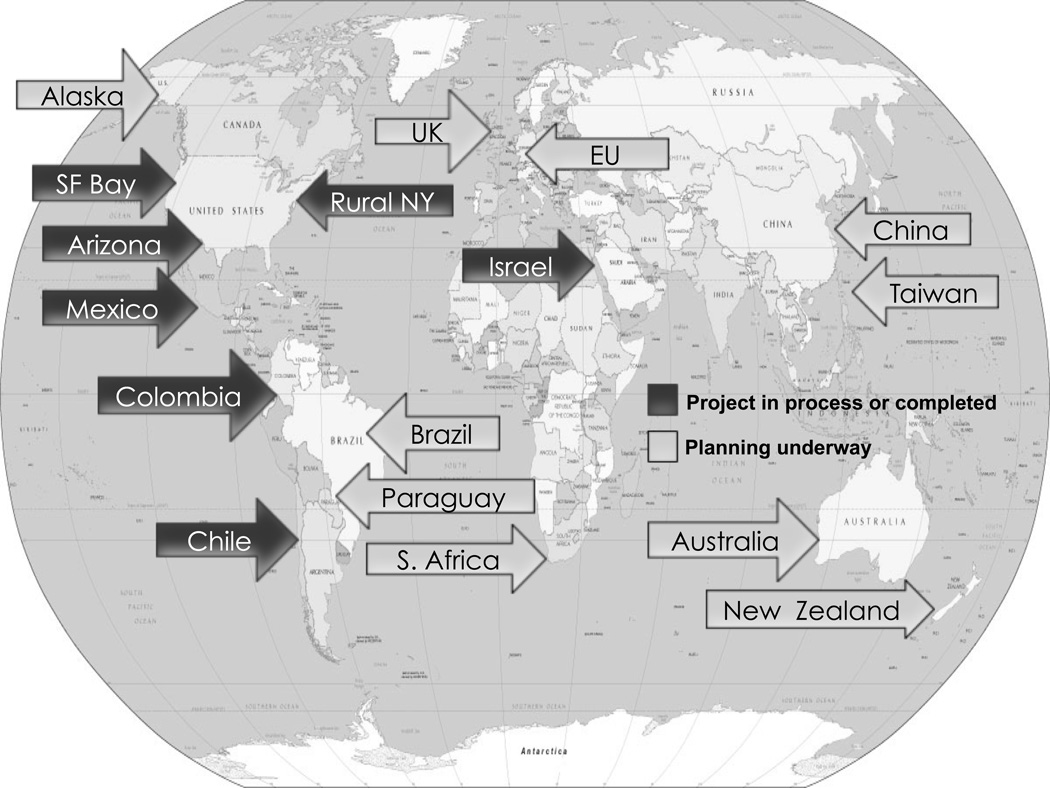

The Discovery Tool is deployed within the “Our Voice” framework, a structured “by the people” process for community assessment, engagement, advocacy, and action. Our Voice shifts the focus away from person-level health behaviors as participants learn how to work together to identify and change aspects of their physical and social environments that impact these behaviors. These environmental changes can in turn help to promote sustainable healthy lifestyles not only for the citizen scientists but also for the greater community. The ultimate goals of these mixed-methods translational research activities are to advance active living, community health, and health equity around the world. An emerging network of global partners is continuing to refine and advance the testing of the Discovery Tool and the Our Voice citizen science framework in a variety of locales, populations, and health contexts (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Emerging Community-Engaged Citizen Science Network for Active Living

Methods

Healthy Neighborhood Discovery Tool

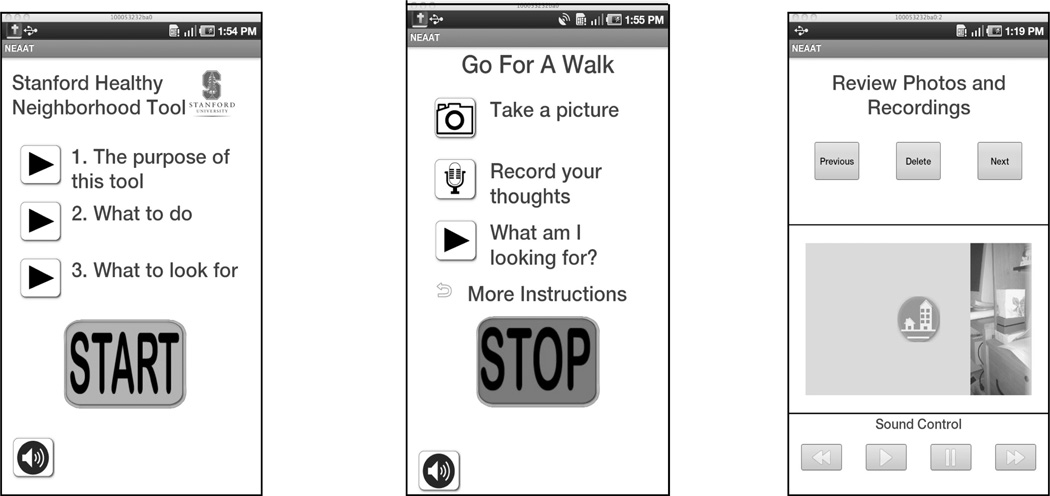

Developed to be user-friendly regardless of education level or technology literacy, the Discovery Tool has been culturally adapted and translated thus far into four languages, as well as three different Spanish versions for the U.S., Colombia, and Mexico (see Figure 2 examples of screenshots). The Discovery Tool enables residents to come together to document neighborhood features through geo-coded photographs, audio narratives, and GPS-tracked walking routes. The Tool also prompts participants to answer a 25-question embedded survey on the specific theme of their assessment (e.g., physical activity, food access) (7). Development and testing of the Tool and accompanying resident engagement process have been supported through grants from a diverse group of multi-sectoral organizations. These include the Office of Community Health and the Center for Innovation in Global Health (Stanford University), the U.S. National Institutes of Health, ESHEL-the Association for the Planning and Development of Services for the Aged in Israel, the County of San Mateo, CA, the Nutrilite Health Institute Wellness Fund, the Bronfenbrenner Center for Translational Research of Cornell University, and the Research Office at the Universidad de Los Andes in Colombia.

Figure 2.

Sample screenshots from the Healthy Neighborhood Discovery Tool

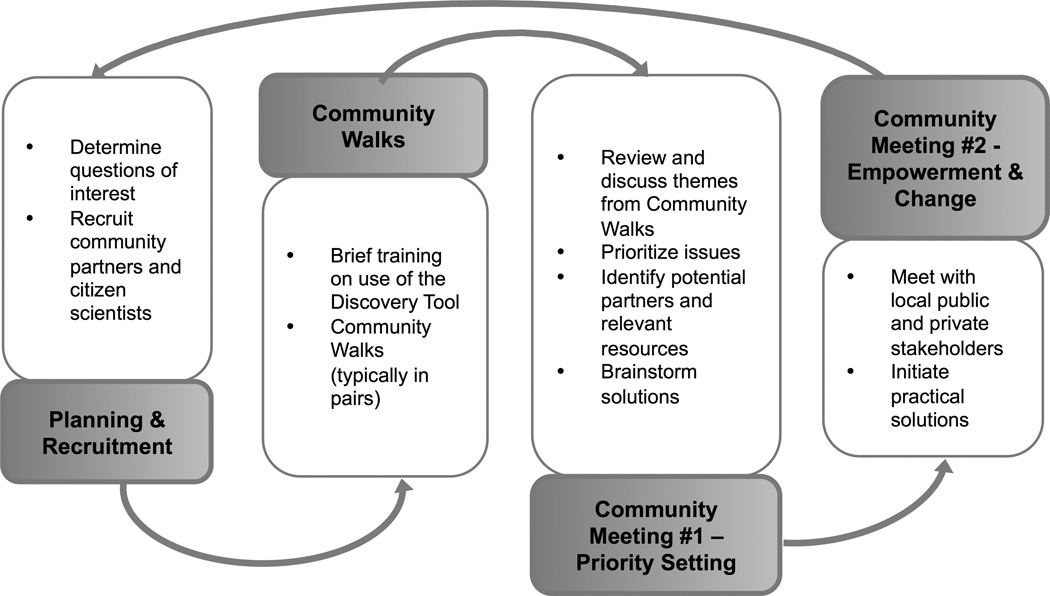

Accompanying “Our Voice” Citizen Science Engagement and Advocacy Framework

While the Discovery Tool can be used alone as a data gathering device to clarify residents’ perspectives on local community matters (see Table 2 for examples), it is most impactful within the Our Voice Citizen Science Framework (see Figure 3), aimed at promoting data-driven changes in the local built and social environments (see Table 3 for examples). As part of Our Voice, residents use the Discovery Tool to collect information on local barriers to and enablers of physical activity (or other relevant behaviors), then learn how to review their data, collectively identify and prioritize relevant issues to address, brainstorm potential solutions, identify community partnerships, and advocate for realistic environmental and policy-level changes with local decision makers (6). Residents convey their findings and recommendations through visual, narrative, and context-based data drawn from the Discovery Tool. In this process, participants frame the problems and possible solutions that are relevant for and readily understood by both the residents themselves as well as local decision-makers and stakeholders (6).

Table 2.

Our Voice Assessment-Only Projects: Citizen Scientist Findings from the Discovery Tool

| Location/Setting | Local Partners | Population of Citizen Scientists (N) |

Main Barriers to Healthy Living | Main Facilitators for Healthy Living |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four census-tract neighborhoods stratified according to SES and walkability, in Cuernavaca, Mexico (15) |

Instituto Nacional De Salud Publica (INSP) |

9 adolescents (mean age 13.4) 32 older adults (mean age 57.3) |

Poor sidewalk quality, presence of trash, negative characteristics of streets, unpleasant aesthetics, safety, dogs, mobility for handicapped, pedestrian crossings |

A running track and well maintained sidewalks, appealing destinations, and the presence of parks or recreational facilities in low SES/low walkability neighborhoods |

| Pop-up park in Los Altos, CA (41) |

Los Altos City Manager’s office; Passerelle Investments, Inc., Los Altos, CA |

9 individuals ranging from adolescents to older adults; 1-mo before-park assessments & 1-mo during-park assessments were completed |

Without the park: construction, an empty block, unwelcoming streets noted (including concerns about safety and isolation) |

During the park: perceptions of community connectedness, family-friendly atmosphere, inviting multi-generational activities in the park were reported |

| Farmers Market in Phoenix, AZ (5) |

Local farmers markets organizers |

38 adults ranging from adolescents to older adults |

No consistent pattern of agreement for neutral or negatively valenced elements |

Food environment: freshness and abundance of produce, product presentation, social interactions and farmers market attractions (e.g., live entertainment, dining offerings) |

| Open Streets projects in San Francisco, CA, Bogotá, Colombia, Temuco, Chile (in process) |

Local activity advocates, biking, walking and public health departments |

Adult residents using the Open Streets programs: San Francisco N=16; Bogotá N=19; Temuco N=8 |

On Non-Open Street days, participants noted a lack of safety, lack of attractive destinations, and absence of healthy food options |

San Francisco:During Open Streets, 75% of residents reported that overall neighbor- hood safety was improved relative to Non- Open St. days (mean improvement rat- ing=4.13 of 5), and 75% of respondents said that the friendliness of the environ- ment was improved (mean improvement rating of 4.19 of 5). Participants also noted increased “sense of community”. Signifi- cant neighborhood differences were noted in perception of ease of walking, width of streets and proximity to destinations. Bogotá: During Open Streets, safety was rated as improved by 84% of participants (mean improvement rating=4.26 of 5), and friendliness of the environment was rated as improved by 95% of participants (mean improvement rating=4.47 of 5). |

Figure 3.

“Our Voice” Citizen Science Framework

Table 3.

Our Voice Assessment +Action Projects Summary of Results

| Citizen Scientist Findings (using Discovery Tool) |

Proximal Outcomes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location/Setting | Local Partners |

Population of Citizen Scientists (N) |

Main Barriers to healthy living |

Main Facilitators for healthy living |

Person-Level | Social/Community- Level |

Built Environment and Policy Level |

| Senior Housing Site in East Palo Alto, CA (6, 7, 49) |

Mid- Peninsula Housing |

Low-income ethnically diverse older adults aged 65+ years (n=22) |

Unsafe street crossings, Lacked fresh produce, Difficult access to services |

Space for garden, Supportive manager |

Significant 9-mo. pre-post changes (p≤.05) in:

|

|

|

| Community residents in North Fair Oaks, CA (50) |

San Mateo County Health System, Health Policy and Planning |

Low-income Latinos:

|

52% of data focused on barriers, most significantly sidewalk quality, trash, and personal safety |

23% of data focused on facilitators, including appealing destinations, well-maintained homes and gardens |

Significant pre-post increases (p<.05) in:

|

|

|

| Community residents in Haifa, Israel (32) |

JDC Israel, Eshel |

Older Jewish and Arab Israelis from:

|

In low-SES neighborhoods: lack of access to open space, public transportation, streetscape

|

Low-SES: sense of community, appealing destinations. High-SES: Access to food- related destinations |

Not assessed |

|

|

| Food Environment Assessment Study (FEAST), N San Mateo County, CA. Community Centers, Senior housing sites (44) |

San Mateo County Health System |

23 low-income ethnically diverse older adults (mean age 70.8 yrs.);

|

Access to healthy food, price and quality Price, health impairments that influenced diet, access to culturally appropriate food stores |

Price, health impairments that influence diet, need to access alternate food stores, price promotion of unhealthy food options |

|

|

|

| Santa Clara County Public Health Dept. Safe Routes to School (In process) |

Santa Clara County Health Department Las Animas Elementary School Brownell Middle School |

7 parents from the elementary school, 30 students from the middle school; 8 staff and school administrators |

Speeding, unsafe drivers, absence of crosswalks, no helmets |

Crossing guards, sidewalks, pedestrian signaling, trails |

Not assessed |

|

|

| 4 rural communities in upstate New York: Chenango, Delaware, Herkimer, Schoharie Counties, NY (42) |

Cornell University Coop Extension Educators |

24 adults (mean age 69.4 yrs.) |

Built environment: unsafe roads & unenforced crosswalks, poor quality sidewalks, vacant buildings and lots, and playground in poor repair; Food environment: high cost, poor quality, and poor selection of health food options |

Built environment: Well-maintained sidewalks connecting desirable destinations (57.7%); Food environment: farmer’s markets, farm stands and gardens as sources of fresh, healthy foods |

Not assessed |

|

|

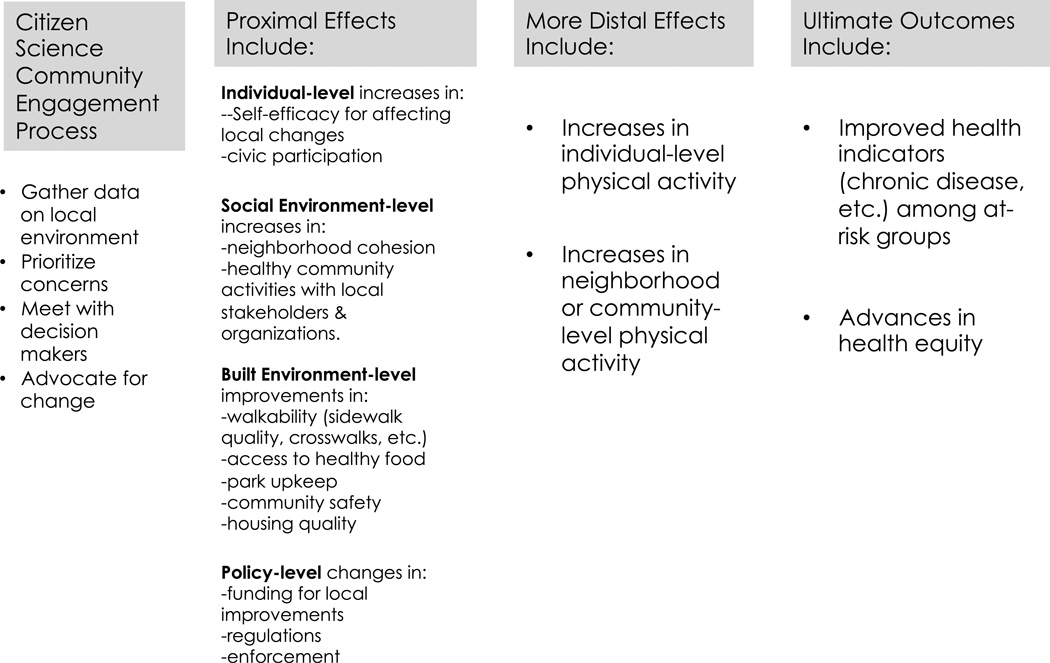

Conceptual Research Model for the Our Voice Citizen Science Framework

The general conceptual research model underlying the Our Voice Citizen Science Framework is summarized in Figure 4. The research model captures multi-level inputs and outcomes, from proximal to more distal putative effects. The inputs and outcomes reflect theories and conceptual frameworks across multiple levels of impact (see overview of relevant theories and frameworks by Kahan et al., 2014) (21), including at the level of the individual (e.g., social cognitive theory; transtheoretical model), the social environment (e.g., social influence theory; diffusion of innovation), built environments (e.g., neighborhood imageability), and the organizational and policy levels (e.g., social identity theory; individualism-collectivism; policy feedback theory). The model begins with the Our Voice citizen science activities described earlier, which are aimed primarily at local social and built environmental impacts (6).

Figure 4.

Citizen Science-engaged Behavioral, Environmental, and Policy Change Research Model

The pilot work completed to date as part of the Our Voice initiative has focused primarily on this first linkage in the model, i.e., the proximal effects of intervention on individual, social, and/or built environmental factors of particular relevance to physical activity promotion in a particular neighborhood. These include changes in participant knowledge and understanding concerning aspects of their neighborhoods or community settings that affect their current physical activity levels; increases in social mobilization activities to promote local consensus building and collective efficacy; increased awareness of the types of changes in relevant neighborhood structures and/or policy decisions that could have future ramifications for neighborhood walkability; and other participant behaviors of potential relevance for increased physical activity. Examples of such behaviors include seeking out additional information on relevant local transit schedules or physical activity programs; telling neighbors, family, and/or friends about such local programs; and pursuing further community advocacy training (44). Assessment of such proximal effects is a reasonable start to model evaluation in light of the observation that changes in local built and social environments represent a putative key factor in promoting sustained physical activity increases at both individual and community levels, but to date have received modest systematic attention outside of natural experimental designs (14).

Following this first stage of the model, applications of experimental and quasi-experimental designs are indicated to systematically evaluate the more distal effects of the citizen science engagement intervention on physical activity promotion and other targeted health behaviors, not only in individual participants but also across the larger neighborhood or community setting. Such outcomes represent the ultimate focus of the model, i.e., to impact physical activity at higher levels of influence that move beyond the individual participant. Such investigations can also provide the opportunity to explore baseline multi-level moderators of intervention success, as well as potential multi-level mediators of change.

The initial results of several of the Our Voice active and healthy lifestyles pilot projects that have occurred to date are highlighted in the Results section. Primary objectives of these early pilot projects were to: a) explore the feasibility and acceptability of using the Discovery Tool to capture the local environments of diverse groups of traditionally underserved residents (e.g., older adults, low-income residents, ethnic minority groups, homeless residents, non-English speakers, those with little familiarity with electronic or mobile health tools); b) ascertain the ease of engagement with which residents were able to accomplish the following Our Voice activities: build group consensus around local built and social environment obstacles to physical activity and healthy living; develop potential realistic solutions; effectively communicate their information and potential solutions with relevant local decision makers; and show willingness to continue to participate in similar citizen science engagement activities in the future; and c) gauge the willingness of relevant decision-makers and stake holders to engage in discussions with residents around the neighborhood issues that they had identified.

Results

To date, the Discovery Tool has been adopted and fully applied by citizen scientists in 10 culturally and economically diverse sites in California, upstate New York, Arizona, Mexico, Israel, Colombia, and Chile. Four of these projects involved the use of the Discovery Tool as part of a neighborhood assessment effort. In these cases, resident voices and perspectives were captured and documented, but the findings were not applied in a facilitated advocacy and action process. For example, citizen scientists used the Discovery Tool to assess a Farmer’s Market in Arizona, a temporary “pop-up” park in northern California, and several “Open Streets” days in North and South America. Project leaders report that their findings will inform and help to refine planning for future events and community projects. Table 2 summarizes the findings from these Assessment-Only projects, which have focused to date primarily on qualitative information gathering related to a specific setting or community event.

The full Our Voice Citizen Science Framework has been applied thus far in six sites, with the guidance and facilitation of local community partners. Citizen scientists were engaged at every stage of the process, generating data, assisting in the coding, and using it to propel subsequent advocacy and action steps. Community partners and facilitators then helped to capture the impacts of this work, documenting outcomes across various levels: individual, social/community, and built environment/policy. A summary of the citizen science project results are reported in Table 3, along with the qualitative information available on achievement of proximal outcomes in these projects.

Assessment-Only Projects

Walkability in Cuernavaca: Exploring the potential of social mobilization for active living in Mexico

Our Voice research activities undertaken in partnership with Mexico’s National Institute of Public Health [INSP]) have occurred in higher- and lower-income Mexican neighborhoods differing on objectively defined “walkability” (13). The citizen science team consisted of 32 older adults and 9 adolescents. As a group, they identified a number of actionable barriers to healthy living, but were challenged by the inaccessibility of decision-makers to help them in moving beyond the assessment phase. Their subsequent citizen science action steps underscored the potential of social mobilization activities that empower residents to “become the solution” in areas where local decision makers may be inaccessible (15). For example, with widespread acknowledgement of the safety and sanitation problems stemming from stray or unleashed dogs, community members promoted a resident-driven “campaign” to shine a spotlight on the issue and encourage residents to leash and clean up after their dogs. Another unique feature of the Mexico implementation was the bridging of the generational divide through discussion of controversial topics such as differing perceptions of street art and graffiti among the older adults and adolescents.

“Open Streets” in Latin America: Evaluating the positive and challenging aspects of community-wide recreational activities and events in Colombia and Chile

Researchers in Bogotá, Colombia, in partnership with U.S. academic partners from the San Francisco Bay area, have developed an innovative protocol to employ the Discovery Tool and citizen science engagement process in evaluating both the barriers to and benefits of the Ciclovía (“Open Streets”) events that occur in Bogotá Sundays and holidays. Preliminary research included adults from a wide range of socioeconomic backgrounds. Initial qualitative assessment of participant reactions indicate that participants perceived that the Ciclovía turned the streets into a safer, more inclusive environment for all (i.e., across age, disability, and socioeconomic strata) (Table 2). In Bogotá, relevant themes reported during the Ciclovía days focused on safety, revitalization of public space, and availability of fruits at the Ciclovía event. The same protocol has been used to evaluate San Francisco’s car-free Sunday monthly event, where residents reported awareness of lack of healthy food choices as well as increased feelings of safety and community connectedness during the event (Table 2). It is also being used currently in Temuco, Chile and San José, CA to evaluate similar issues in these locales. The use of the same protocol in these four localities will promote a better understanding of the relative benefits of such recreational activities to community physical activity, health, and wellbeing as well as the barriers to participation in different countries and cultures, including the U.S. Quantitative analysis from these projects is currently ongoing.

A Pop-up Park in Northern California: Engaging residents in more affluent communities around novel active living solutions

The initial development and testing of the Discovery Tool and citizen science engagement process was aimed at reaching lower-income, less educated populations who traditionally have little voice in their communities or the local decisions that impact them (7). Yet, clearly, local built environment issues impact more affluent communities as well. To explore the initial acceptability of the Discovery Tool and citizen science engagement process in such communities, a pilot study was undertaken involving the evaluation of a temporary “pop-up” park—a novel means of promoting active living in urban areas (41). Nine residents, ranging in age from teenagers to older adults, used the Discovery Tool to evaluate the “pop-up” park at three time points (before, during, and after the street was closed to accommodate the park) (Table 2). While the park was in place, the participant group reported that the area was welcoming and inviting, but before and after the park they described the area as lonely and empty. The participant group also reported a sense of connectedness and community during the park that was not noted before or after the park. Positive park features that were noted included artificial grass, a chalkboard and drawing area for children, outdoor furniture that included shade umbrellas, a park events notice board, live music, and planters with foliage. Nearby construction was noted as a negative feature. The Discovery Tool was found to be efficient and useful for evaluating this type of novel intervention, and the citizen science process was found to be readily acceptable by residents living in this more affluent community.

An Urban Farmer’s Market in Arizona: Assessing the contextual elements that may impact food choices and use

Shoppers at an urban farmer’s market in Arizona used the Discovery Tool to document features that enhanced or detracted from their farmers’ market shopping experience (5). In addition to the freshness and abundance of produce being of primary importance to shoppers, product presentation, social interactions and farmers’ market attractions were also noted as features that enhance the shopping experience. This information was provided to the organizers of the farmers’ market to inform targeted interventions to increase farmers’ market utilization, community-building and social marketing strategies (5).

Assessment + Action Projects

Senior Housing in Northern California: Engaging low-income senior housing residents to improve local environments for active living

In the first and longest-running Our Voice citizen science project to date, residents living in a public senior housing setting in East Palo Alto, CA—a low-income ethnically diverse city in northern California--received support from researchers and the housing manager in using the Discovery Tool to assess neighborhood factors that made it difficult to walk to destinations as well as make healthful food choices (6). The 22 citizen scientists formed a Community Advocacy Team and used their data gathering and reporting as a foundation for forging a long-term relationship with representatives of the City Planning Department. The Planning Department’s decisions were informed by this ongoing engagement with the citizen scientists, with the subsequent allocation of $1 million by the City Council (derived from a grant from the Strategic Growth Council) for planning and related activities to create a safer “public health” environment (49). Actions taken by the City Council included conducting an environmental analysis of the community, updating the City general plan to ensure health was more purposefully included in future planning, reviewing the streetscapes and pathways around the senior housing site to create a safer walking environment and better access to the local senior center, and implementing a comprehensive sidewalk inventory and repair program. In addition, the perspectives of the older adult citizen scientists were incorporated in a community Senior Advisory Committee resolution that was subsequently adopted to address constraints to active living. The Community Advocacy Team has continued its advocacy within the senior housing site, holding well-attended resident meetings (>40% participation), partnering with non-profit organizations to reinvigorate an unused community garden, and attending on-site cooking classes to learn new ways to eat the homegrown produce (6, 49). Unfortunately, in this first-generation study there was not sufficient information available to capture cooking class frequency and attendance rates.

In addition to the above environmental and policy activities for which the citizen science participants were active contributors and facilitators, participant evaluations prior to the start of the project and nine months later reflected significant changes in participants’ perceptions related to their local built and social environments. For example, they reported a decrease in their perceptions that “people in this neighborhood generally don’t get along with each other” (mean change from 3.7 to 3.1 on a 5-point scale, p=.05); a decrease in their perceptions that “there is a large selection of fresh fruits and vegetables available in my neighborhood” (change from 1.25 to 0.4 on a 4-point scale, p=.05); and an increase in their perceptions that “the speed of traffic on most nearby streets is usually slow (30 mph or less)” (change from 1.75–1.9 on a 4-point scale, p=.05). Perceptions of whether residents viewed their neighborhood as “close-knit” also tended to increase during this period (change from 3.35 to 4.2 on a 5-point scale, p=.10).

Generating neighborhood solutions in Northern California: Bringing Latino residents together to make their voices heard

Twenty adolescent and older adult “citizen scientists” from a low-income community of predominantly first-generation Mexican immigrants gathered and synthesized data on barriers and facilitators to active living. They then learned how to engage in productive dialogue with local policymakers to share their concerns about what they had found, including illegal dumping of trash and other objects on neighborhood sidewalks that impeded walking (50). This experience with policy advocacy led to the formation of a Community Advisory Board to research and provide guidance regarding best practices to improve the health of the community. This group then developed a Community Resource Guide that included contact details for local service providers such as the Sheriff’s office, the privately owned waste management company, and relevant City and County officials (50). In addition, this pilot study found significant pre- to post-intervention increases in several important variables related to personal self-efficacy, neighborhood cohesion and community engagement, measured using a 5-point scale of from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. These included feeling that “this is a close-knit neighborhood” (mean change from 2.9 to 4.0), “I can influence decisions that affect my community” (mean change from 1.75 to 3.75), “By working together with others in my community I can influence decisions that affect my community” (change from 1.38 to 3.25), and “People in my community have connections to people who can influence what happens in my community” (change from 2.0 to 3.75) (p values < .05).

Multi-cultural dialogue in Israel: building neighborhood solutions among diverse older adults

As the world’s communities become increasingly multi-cultural, identifying the best ways for helping residents bridge cultural and language divides has become especially critical. Activation of neighborhood citizen scientists offers an approach to facilitating dialogue between residents from different cultures and backgrounds through focusing on a shared locale that people care about deeply (e.g., their own neighborhoods) as well as a shared purpose (making their neighborhoods and communities more supportive of active, healthy lifestyles). In Israel, researchers and a national non-governmental organization partnered to conduct initial testing of the Our Voice citizen engagement project among older residents in three northern cities (32). A total of 135 citizen scientists (69 from low-SES neighborhoods and 66 from high-SES neighborhoods) identified barriers and facilitators to physical activity in their respective communities. A major aim of this project was to begin to develop environmental and community strategies to improve walkability in the targeted neighborhoods (e.g., by keeping sidewalks accessible for pedestrians). At the social/community level, the multigenerational citizen science effort gave rise to the formation of walking groups, a series of three lectures on health issues in seniors centers attended by 50 participants, and a tai-chi group attended by both Israeli-born residents and immigrants primarily from the former USSR. At the built environment level, older adult-friendly walking routes and maps were created. One of the more popular walking routes (named the “Golden Path”) was launched at an event led by the city’s mayor and included more than 300 senior citizens. Members of the research team and community members walked this route with municipal workers pointing out barriers along the way, following which the municipality made incremental environmental changes along the route, such as adding curb cuts, filling holes, and painting sidewalks with new color (32).

An additional successful outcome of the Our Voice-Israel project has been the ready uptake of citizen science and community engagement activities in primarily Arab, primarily Jewish, and mixed ethnicity neighborhoods. Anecodotal evidence indicates that many participants found the project meaningful and reported that it helped them connect to their neighborhood and community (32). Through use of resident translators and opinion leaders, the diverse parties were successful in creating a shared purpose and set of goals for improving their neighborhoods for all. The specific “lessons learned” from such successes can be translated for potential application or adaptation to the increasing number of multi-cultural neighborhoods and communities found across the U.S. and elsewhere.

Food access in low-income Northern California communities: Understanding and overcoming obstacles

Ready access to desirable, healthful, and reasonably priced food is beyond the grasp of an alarmingly large number of community residents, even in affluent, industrialized nations (1, 8). The Food Environment Assessment Study (FEAST), funded by the Get Healthy San Mateo County initiative in northern California (see Video, Supplemental Content, the FEAST project), sought to better understand the facilitators of and barriers to food access and availability among the area’s low-income, ethnically diverse older adult residents – half of whom reported experiencing food insecurity in the last 30 days (44). A total of 23 senior citizens were trained to identify and prioritize the most important issues impacting their ability to obtain healthful food. The group idenfitied the need for more variety and better pricing for healthy foods. In an evaluation three months after implementation of the FEAST project, 84% of the participating citizen scientists reported that their experience had led them to contact a local policy maker, use a new community service (e.g., food stamps, shuttle service), and/or share information with a friend (44). Six months following the end of this project, a subset of the citizen scientists (N=9) requested additional advocacy training and formed a Senior Advocacy Team (SAT). Three months later the SAT held an open forum at the housing site, to which City and County policymakers were invited. Within four days of this meeting, changes to street signage were made and a dangerous street curb was repaired, improving the traffic safety at the affordable senior housing site. Twelve months following the end of this project, members of the SAT attended the 5th Annual Affordable Senior Housing Resident Advocacy in Sacramento, CA—the state capital. The SAT representatives were among 140 affordable senior housing residents, administrators, and service coordinators that met with legislators to advocate for increased funding for affordable senior housing. The SAT continues to be active around health-related issues affecting their community.

“Safe Routes to School” in Santa Clara County, CA

In 2015, Santa Clara County Department of Public Health expanded a county-based initiative to increase safe, affordable, and health-promoting options for children to get to and from school to the southernmost part of the county, which tends to be more rural than other parts of the county. In an effort to increase resident participation in this activity, Our Voice was implemented at one elementary school and one middle school. The band of citizen scientists trained and deployed for the task included 30 school-aged children and seven parents. Eight staff and school administrators also participated. The citizen scientists documented a number of safety risks near the schools, including speeding or otherwise unsafe drivers, lack of crosswalks, and children riding bicycles without helmets. These observations led to the development of a Community Task Force, the establishment of “Walking Wednesdays” and a “Walking School Bus,” and a bike assembly at the school to promote safe riding. In the community meetings, local policy makers were enthused by the citizen voice and invited the lay scientists to present to the City of Gilroy’s Bicycle and Pedestrian Commission and to collaborate with city engineers on development of a 3-year action plan. County staff reported that the excitement about Our Voice – and the community engagement it spurred – provided a sharp contrast to the County’s work at other schools, where getting students and parents involved had generally proven less successful.

Seniors getting active in rural New York: improving physical activity and eating environments in rural communities

Twenty-four older adult citizen scientists from four rural communities in New York State used the Discovery Tool to identify barriers and facilitators to healthy eating and active living (42). They documented a number of barriers to physical activity, including local roads that were unsafe due to lack of signage or unenforced crosswalks, poor sidewalk quality, and vacant buildings and lots. Barriers to healthy eating in rural environments included high cost, poor quality, and lack of availability of healthful foods. Facilitators of physical activity included having walkable destinations to visit, good quality sidewalks and pleasing aesthetics. An important facilitator of healthy eating was access to healthy foods, which took many forms including bulk shopping from supermarkets out of town; using non-traditional food stores such as pharmacies and convenience stores for staples such as milk, eggs and bread; and purchasing locally grown produce at farmers markets and farm stands or cultivating their own gardens (42). Following their assessment, the citizen scientists developed a civic engagement group “to increase physical activity year-round for all ages.” They also partnered with several community organizations to create plans and raise funds for the development of a “Fun and Fitness Area” in the town’s rundown former playground.

It was noteworthy that a number of these themes were also identified, as described earlier, by citizen scientists from urban locations in California, Mexico, and Israel, including the quality of roads and sidewalks, the presence of destinations to visit, the presence of parks and community aesthetics, and mobility and access issues. In contrast, observations about trash, personal safety, and street features were noted by urban residents though not by rural residents, and the presence of places to rest while walking were noted more frequently by rural than by urban residents.

Bringing Potential Active Living Solutions to Different Countries and Cultures

As applications of the Our Voice Framework proliferate and are adapted to meet local needs, so too will the methods for evaluating impacts over time. Based on the reported experiences to date, a number of themes merit further exploration, as described below.

Country-of-origin solution generation for immigrant populations

The expansion of diverse immigrant populations in North America, Europe, and other parts of the world provides an opportunity to better understand how individuals’ countries of origin shape the ways in which they perceive and interact with the physical and social environments in their adopted countries. For example, the lessons learned from Mexico described earlier indicated that more “inward-focused” solutions that relied on social mobilization within the neighborhood itself were prominent, in contrast to the primarily “outward-focused” strategies (i.e., looking to local organizations or decision makers for help) applied in the impoverished Latino immigrant community in northern California. The Mexican social mobilization “skillset” could serve as a useful model for Mexican immigrant communities in the U.S., as well as other low-income communities in underserved sections of the U.S. and other countries—particularly those without ready or easy access to local decision makers.

Expanding the use of wearable IT in broadening citizen science capabilities

The rapid emergence of hands-free information technologies broadens the types of applications of the Our Voice approach to additional populations and contexts. For example, we have systematically compared the utility of user-driven photo image capture occurring with the Discovery Tool versus automated photo image capture occurring with the use of SenseCam and similar devices (43). The results from this research indicated that almost all of the data captured automatically by the SenseCam (96%) was also captured by participants using the Discovery Tool (43). For the 4% of images recorded by the SenseCam and not recorded by the participants via the Discovery Tool there were generational differences–-adolescents appeared to overlook positive features of their neighborhood, perhaps taking them for granted, whereas older adults tended to overlook negative features of their neighborhood, perhaps because they had become habituated to their surroundings (43). Meanwhile, the Discovery Tool captured important built environment elements (i.e., dogs, graffiti) that were not captured by the SenseCam (43).

Similarly, formative comparison testing between the Discovery Tool and other types of hands-free information technologies (e.g., Google Glass and similar wearable devices that contain photo, GPS, and audio narrative capabilities) would be informative and could broaden the applicability of the Our Voice approach for different populations and situations. For example, such hands-free device capabilities would allow not only walkers but also cyclists participating in local Ciclovías to contribute citizen science information (given that such a use-case is infeasible using a hand-held e-tablet device).

Giving voice to intergenerational problems and solutions for active living

The international “8–80” cities initiative has shone a spotlight on built environment issues that cut across age groups and generations. While built environment problems can often disproportionally affect the young and old alike, so too can older and younger generations work together to identify the challenges and generate mutually beneficial solutions. In addition to the Latino immigrant neighborhood in northern California, Our Voice partners in Mexico and Israel have brought young teens and pre-teens together with older adults in using the Discovery Tool to collect relevant information about their neighborhoods that has spurred intergenerational discussions and problem-solving of potential solutions. In addition, Arab residents reported that involving youth was particularly inspiring—children there were enthusiastic about the e-tablet-based Discovery Tool and were eager to help the adults use it. A “ripple effect” was reported in that community, where the youth were excited to come up with other places (e.g., their school) to use the Discovery Tool to capture their experiences (32).

Similarly, in Mexico, participation in the Our Voice activities by both youth and older adults led to lively discussions and consensus-building around solutions that were acceptable to both age groups. For instance, while during their walks around the neighborhood older adults labeled the graffiti that was present as uncomfortable and a nuisance, the younger participants considered it to be acceptable and not a deterrent to walking in the neighborhood. The ensuing discussions between the two age groups helped to place this neighborhood element in a new light, and led to increased awareness and insights on both sides.

The technology-based Our Voice approach can empower individuals across the age spectrum to advocate for neighborhood and other community setting-based improvements (e.g., at schools, worksites, housing settings, etc.) that have the potential to benefit whole communities, reduce health disparities, and improve wellbeing and quality of life.

Solutions that take aim at healthy aging

The world—including both industrialized and developing nations—is aging, and few countries are prepared to handle the health care, economic, and social consequences accompanying an aging society. Given the demonstrated links between built environments and day-to-day physical activity, function, and wellbeing among older adults, promoting environments that facilitate active engagement, agency, and vitality as people age is an important goal globally. An example from the Our Voice project in Israel is the co-creation by citizen scientists, researchers, and non-profit partners of walking maps called “The Golden Path” that highlight safe and easy walking routes for older adults; information about features important to older adults such as the location of benches and toilets; and the location of stores designated as particularly welcoming to older adults by way of a “Golden Path” sign in the window (32). In the next phase of the project, local partners plan a social marketing campaign for the “Golden Path” that would include path markers and window signs for local businesses (10).

Translating citizen science findings and recommendations into policy actions

The explicit goals of the citizen science-community engagement initiative are to build resident capacity and skills for successfully enacting environmental and policy changes in their own communities. This approach has been developed with flexibility in mind in order to adapt to the prevailing decisional landscape within a global context. For example, in countries like Israel and the U.S. where elected officials are generally responsive to the concerns of their constituents, Our Voice partners have found that connecting the citizen scientists directly with local decision makers (after some training on both sides, so that each side is sensitive to the perspectives of the other) is the appropriate course of action. This has generally also been the case in Bogotá, Colombia, particularly in areas related to the Ciclovía program. In contrast, in countries like Mexico, there is less direct communication between the citizenry and local policy makers. This structural “disconnect” may lead to more socially-based actions (e.g., formation of a neighborhood coalition for ameliorating problems related to dogs in the neighborhood; neighborhood watch groups; increasing cohesion among neighbors to increase safety, etc.), as opposed to advocating for larger infrastructural or built environment changes for which they would need governmental support. Our Mexican partners have reported that tapping nationally respected colleagues, such as academic researchers, to carry their information to policy makers and other decision makers may also be an appropriate and effective course of action. Partnering with nongovernmental or other civic organizations is another way of addressing built environment changes requiring larger infrastructural modifications. Such organizations have been demonstrated to be critical advocates for policy change in Mexico (e.g., they were instrumental for the approval of the federal sweetened beverage tax) (2).

Understanding the Strengths and Challenges of the Citizen Science Approach

Among the strengths of the citizen science engagement approach are its ability to a) allow diverse groups of residents, irrespective of education or other resources, to be part of the problem identification process and contributors to realistic solution-building; b) help articulate community priorities and values while highlighting local problems that are actionable; c) create mutual understanding between residents, local stakeholders, and decision-makers in a collaborative, solution-oriented environment; and d) make use of multi-layered qualitative and quantitative data that may promote changes at multiple levels of impact.

One of the primary challenges in building this intervention was to develop a simple, portable electronic data-gathering interface that all residents could use, irrespective of age, education, culture, or technology literacy. The Discovery Tool development process involved extensive use of a behavioral science-informed user experience design process that involved a collaborative process of refining the tool together with partners to mitigate this issue (18, 29). The pilot studies undertaken with the Discovery Tool have demonstrated that individuals from different cultures who were as young as 11 and as old as 92 years could use this tool to gather relevant neighborhood data. An important additional challenge concerned the employment of relevant community-based participatory research strategies (47) to “kick-start” the citizen science engagement process in diverse communities. We found that initial entry points for starting this process can vary, including initiation by community-oriented researchers, community organizations, federal agencies, industry partners, and, conceivably, by residents themselves. An important part of this process is trust-building among residents (many of whom were isolated from civic engagement activities in their communities), researchers, local organizations, and decision-makers. Finally, challenges that remain to be tested include identifying specific, culturally relevant methods for fostering sustainability and scalability of the citizen science engagement process.

Discussion and Next Steps

Results thus far indicate the initial promise of the globally developed and refined Our Voice Citizen Science Framework in enabling residents from diverse cultural, geographic, and socioeconomic backgrounds to collect relevant information about their local physical and social environments. This information can in turn be successfully applied in promoting initial environmental changes that have been associated consistently in the literature with more active and healthy lifestyles (6). While this first-generation set of projects has targeted proximal outcomes at the individual, community, built environment and policy levels, the next phase will be aimed at three longer-term objectives: a) the systematic evaluation of the impacts of this intervention on changes in person-level physical activity and other relevant health behaviors, both among citizen scientists themselves, and among their neighbors; b) the evaluation of the impacts of the intervention on changes in other individual- and neighborhood-level outcomes, including individual and collective agency and civic engagement as well as day-to-day well-being and quality of life; and c) identification and testing of methods both to foster ongoing sustainability of intervention processes and successes, and to disseminate the work to other relevant problem areas and communities. Anecdotal accounts that have indicated interest among residents and participating organizations in extending the use of the Discovery Tool and the Our Voice Citizen Science Framework to other locales and problem areas is encouraging. Applications of the Our Voice initiative will be further informed by “use cases” proposed or under development in Asia (e.g., Taiwan, China, Cambodia), Central and South America (e.g., Brazil, Chile, Paraguay), Europe (e.g., UK, Germany, Switzerland), Africa (e.g., South Africa), Australia, and New Zealand.

The first-generation international work that has occurred through the Our Voice initiative to date has shown, remarkably, that while differences in barriers to active and healthy living have arisen based on culture or geography (e.g., wild pigs—as opposed to loose dogs--as a deterrent to walking in some Israeli neighborhoods), a number of similar barriers and enablers were identified across the diverse locales studied thus far (e.g., lack of safe walking paths and routes; traffic concerns; lack of attractive destinations or public transit). These results increase the likelihood that innovative solutions identified in one country could be potentially applicable and/or adaptable to other countries.

To date, the initial U.S. and international successes of the Our Voice projects have been shared in various scientific reports, publications, and professional and community meetings. News of the projects has reached the public by way of video and print media productions. Future goals include the development of an international electronic and social media-supported global network, which would provide a “home base” for sharing, supporting and disseminating the Our Voice applications and discoveries. Such a network could also help to ensure the application of the most advanced ICT to support citizen science endeavors, including automated downloading of the Discovery Tool app and advocacy training materials, and easy-to-use uploading processes for outcome reports and information along with geocoded photos and audio narratives.

Currently the Our Voice model has been tested alone. Given, however, the demonstrated efficacy of a number of theory-based person-level intervention strategies which target individual-level factors involved in behavior change (22), combining such interventions with the higher-level Our Voice skill building described earlier may be particularly powerful. Such expanded, multi-level intervention approaches deserve systematic evaluation.

The longer-term vision of the Our Voice initiative is to create a global movement of intergen-erational, community-engaged citizen scientists and supporting community organizations and policy makers, connected via a worldwide communication and exchange network. The ultimate goal is to set in motion a self-sustaining process of citizen science engagement and empower-ment that leads to local environmental changes that in turn foster the sustained salutary choices and behaviors that create a healthy and vital life for all. In this way, a “culture” of active living, health, and wellbeing can flourish across cultural, geographic, and socioeconomic boundaries.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The northern California projects were supported in part by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH (UL1RR025774) through two Clinical Translational Science Seed Grants awarded through the Stanford Office of Community Health (King, Buman, Winter), a Stanford Center for Innovation in Global Health Seed Grant (King, Winter, Rosas, Salvo), Get Healthy San Mateo County Implementation Funding (King and Sheats), U.S. Public Heath Service Grant 5T32HL007034 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (PI: C Gardner), U.S. Public Health Service Grants 1R01 HL116448 and 1R01DK102016 (King), U.S. Public Health Service Grant 1U54EB020405 supporting The National Center for Mobility Data Integration and Insight (PI: S. Delp), The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Grant ID#73344 (King), and the Nutrilite Health Institute Wellness Fund provided by Amway to the Stanford Prevention Research Center. The Israel project was funded by JDC Eshel Israel grant #161992 (Garber). Cornell University’s rural New York State project was funded by the Bronfenbrenner Center Innovative Pilot Studies Program of the Cornell University Bronfenbrenner Center for Translational Research (Seguin). Colombia’s project was funded through the Research Office at the Universidad de los Andes (Sarmiento).

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance and support of the following individuals in project activities: Brent Butler, Benjamin Chrisinger, Dominique Cohen, Jill Evans, Eric Hekler, Beverly Karnatz, Rhonda McClinton-Brown, Elizabeth Mezias, Jennifer Otten, Priscilla Padilla-Romero, Jasneet Sharma, Cristina Ugaitafa, Angela Waters, Amy Woof, and Cathleen Baker and colleagues at the San Mateo County, CA Health System (northern California); Shlomit Ergon, Neta HaGani, and Dov Sugarman (Israel); Leah Connor, Jeanne Darling, Marilyn Janiczek, Linda Robbins, and Betty Clark (Cornell); David Cortes and Giovanna Gatica (Mexico); Alice Kawaguchi, Alica Arce, Michelle Wexler, Laura Jones, Andrea Flores-Shelton, Lidia Doniz, Nicole Coxe, Jyll Stevens, Susan Lowery, and Tonya Veitch (Santa Clara County Public Health Department, CA); and Yalta Alvira, Yeremin Fajardo, Oscar Pinilla, and Ricardo Perdomo (Colombia). We thank the YMCA of the Bay Area for supporting the recruitment of participants in the Bayview and Buchanan districts of San Francisco (Zieff).

The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by ACSM.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental Content

Supplemental Content 1—90 Sec Feast HD 1080pConverted.avi: The FEAST Project

References

- 1.Ballard TJ, Kepple AW, Cafiero C. The food insecurity experience scale: Developing a global standard for monitoring hunger worldwide. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO); 2013. Available from: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barquera S, Campos I, Rivera JA. Mexico attempts to tackle obesity: the process, results, push backs and future challenges. Obes Rev. 2013;14(Suppl 2):69–78. doi: 10.1111/obr.12096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonney R, Cooper CB, Dickinson J, et al. Citizen science: A developing tool for expanding science knowledge and scientific literacy. BioScience. 2009;59(11):977–984. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bücheler T, Sieg JH. Understanding science 2.0: Crowdsourcing and open innovation in the scientific method. Procedia Computer Science. 2011;7:327–329. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buman MP, Bertmann F, Hekler EB, et al. A qualitative study of shopper experiences at an urban farmers’ market using the Stanford Healthy Neighborhood Discovery Tool. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(6):994–1000. doi: 10.1017/S136898001400127X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buman MP, Winter SJ, Baker C, Hekler EB, Otten JJ, King AC. Neighborhood eating and activity advocacy teams (NEAAT): Engaging older adults in policy activities to improve built environments for health. Translat Behav Med. 2012:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0100-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buman MP, Winter SJ, Sheats JL, et al. The Stanford Healthy Neighborhood Discovery Tool: a computerized tool to assess active living environments. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(4):e41–e47. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory C, Singh A. Household food security in the United States in 2014. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2015. Available from: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Danaei G, Ding EL, Mozaffarian D, et al. The preventable causes of death in the United States: comparative risk assessment of dietary, lifestyle, and metabolic risk factors. PLoS Med. 2009;6(4):e1000058. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eshel. Health Promoting Environments: Phase 2 Project Proposal. Jerusalum, Israel: ESHEL-the Association for the Planning and Development of Services for the Aged in Israel (JDC Israel) 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eyler AA, Matson-Koffman D, Vest JR, et al. Environmental, policy, and cultural factors related to physical activity in a diverse sample of women: The Women’s Cardiovascular Health Network Project--Summary and Discussion. Women and Health. 2002;36:123–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fjeldsoe B, Neuhaus M, Winkler E, Eakin E. Systematic review of maintenance of behavior change following physical activity and dietary interventions. Health Psychol. 2011;30(1):99–109. doi: 10.1037/a0021974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frank LD, Sallis JF, Saelens BE, et al. The development of a walkability index: application to the Neighborhood Quality of Life Study. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44(13):924–933. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.058701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giles-Corti B, Bull F, Knuiman M, et al. The influence of urban design on neighbourhood walking following residential relocation: longitudinal results from the RESIDE study. Soc Sci Med. 2013;77:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldman Rosas L, Buman MP, Castro CM, et al. Harnessing the capacity of citizen science to promote active living in California and Mexico. Conference on Place, Migration and Health; Bellagio, Italy. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goode AD, Reeves MM, Eakin EG. Telephone-delivered interventions for physical activity and dietary behavior change: an updated systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(1):81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris JR, Burton P, Knoppers BM, et al. Toward a roadmap in global biobanking for health. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20(11):1105–1111. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hekler EB, King AC, Banerjee B, et al. A case study of BSUED: Behavioral Science-informed User Experience Design. Proceedings of the Chi 2011; Vancouver, B.C., Canada. 2011. pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hinyard LJ, Kreuter MW. Using narrative communication as a tool for health behavior change: a conceptual, theoretical, and empirical overview. Health Educ Behav. 2007;34(5):777–792. doi: 10.1177/1090198106291963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ioannidis JP, Adami HO. Nested randomized trials in large cohorts and biobanks: studying the health effects of lifestyle factors. Epidemiology. 2008;19(1):75–82. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31815be01c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kahan S, Gielen AC, Fagan PJ, Green LW. Health Behavior Change in Populations. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kahn EB, Ramsey LT, Brownson RC, et al. The effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity. A systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22(4 Suppl):73–107. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00434-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelty C, Panofsky A. Disentangling public participation in science and biomedicine. Genome Medicine. 2014;6(1):8. doi: 10.1186/gm525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King AC. The coming of age of behavioral research in physical activity. Ann Behav Med. 2001;23(4):227–228. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2304_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.King AC. Behavioral medicine in the 21st century: transforming “the Road Less Traveled” into the “American Way of Life”. Ann Behav Med. 2014;47(1):71–78. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9530-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.King AC, Buman M, Hekler E. Physical activity and behavior change. In: Kahan S, Gielen AC, Fagan PJ, Green LW, editors. Health Behavior Change in Populations. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2014. pp. 262–293. [Google Scholar]

- 27.King AC, Friedman RM, Marcus BH, et al. Ongoing physical activity advice by humans versus computers: The Community Health Advice by Telephone (CHAT) Trial. Health Psychol. 2007;26:718–727. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.King AC, Glanz K, Patrick K. Technologies to measure and modify physical activity and eating environments. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(5):630–638. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.King AC, Hekler EB, Grieco LA, et al. Harnessing different motivational frames to promote daily physical activity and reduce sedentary behavior in aging adults. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e62613. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, et al. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. 2012;380(9838):219–229. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marshall NJ, Kleine DA, Dean AJ. CoralWatch: Education, monitoring, and sustainability through citizen science. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2012;10:332–334. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moran M, Werner P, Doron I, et al. Detecting inequalities in healthy and age-friendly environments: Examining the Stanford Healthy Neighborhood Discovery Tool in Israel. International Research Workshop on Inequalities in Health Promoting Environments: Physical Activity and Diet; Haifa, Israel. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naci H, Ioannidis JP. Evaluation of wellness determinants and interventions by citizen scientists. JAMA. 2015;314(2):121–122. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.6160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Norman GJ, Zabinski MF, Adams MA, Rosenberg DE, Yaroch AL, Atienza AA. A review of eHealth interventions for physical activity and dietary behavior change. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(4):336–345. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oberhauser K, LeBuhn G. Insects and plants: Engaging undergraduates in authentic research through citizen science. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2012;10(6):318–320. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Papoutsi GS, Drichoutis AC, Nayga RM. The causes of childhood obesity: A survey. J Economic Surveys. 2013;27(4):743–767. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pleis JR, Ward BW, Lucas JW. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2009. 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rabeharisoa V. The struggle against neuromuscular diseases in France and the emergence of the “partnership model” of patient organisation. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(11):2127–2136. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raddick MJ, Bracey G, Gay PL, Lintott CJ, Murray P, Vandenberg J. Galaxy Zoo: Exploring the motivations of citizen science volunteers. Astronomy Education Review. 2010;9(1) [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sallis JF, Floyd MF, Rodriguez DA, Saelens BE. Role of built environments in physical activity, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2012;125(5):729–737. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.969022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salvo D, Sheats JL, Winger SJ, et al. Are pop-up parks a sustainable strategy to promote active living in urban spaces? An evaluation of the effects of a Los Alto, CA pop-up park in 2013 and 2014. Active Living Research Annual Conference; San Diego, CA. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seguin RA, Morgan EH, Connor LM, et al. Rural food and physical activity assessment using an electronic tablet-based application, New York, 2013–2014. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:E102. doi: 10.5888/pcd12.150147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheats JL, Winter SJ, Padilla-Romero P, Goldman-Rosas L, Grieco LA, King AC. Comparison of passive versus active photo capture of built environment features by technology naïve Latinos using the SenseCam and Stanford Healthy Neighborhood Discovery Tool. Proceedings of the SenseCam 2013; San Diego, CA. 2013. pp. 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sheats JL, Winter SJ, Padilla-Romero P, King AC. FEAST (Food Environment Assessment using the Stanford Tool): Development of a mobile application to crowdsource resident interactions with the food environment. Ann Behav Med. 2014;47:S264. (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 45.Slovic P, Finucane ML, Peters E, MacGregor DG. Risk as analysis and risk as feelings: some thoughts about affect, reason, risk, and rationality. Risk analysis : an official publication of the Society for Risk Analysis. 2004;24(2):311–322. doi: 10.1111/j.0272-4332.2004.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Viswanath K, Kreuter MW. Health disparities, communication inequalities, and eHealth. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(5 Suppl):S131–S133. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: The intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am J Public Health. 2009 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036. [Internet] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wiggins A, Crowston K. From conservation to crowdsourcing: A typology of citizen science. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Science (HICSS); Honolulu, Hawaii. 2011. pp. 1–10. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Winter SJ, Buman MP, Sheats JL, et al. Harnessing the potential of older adults to measure and modify their environments: long-term successes of the Neighborhood Eating and Activity Advocacy Team (NEAAT) Study. Transl Behav Med. 2014;4(2):226–227. doi: 10.1007/s13142-014-0264-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Winter SJ, Goldman Rosas L, Padilla Romero P, et al. Using citizen scientists to gather, analyze, and disseminate information about neighborhood features that affect active living. J Immigrant Minority Health. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10903-015-0241-x. PMCID: PMC4715987; PMID: 26184398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.World Health Organization. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2010. Available from: WHO. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]