Graphical abstract

Keywords: Antibiotics, Aeribacillus pallidus SAT4, Production, Characterization

Abstract

A novel thermophilic bacterial strain of the genus Aeribacillus was isolated from Thar Dessert Pakistan. This strain showed significant antibacterial activity against Micrococcus luteus, Staphylococcus aureus, and Pseudomonasaeruginosa. The strain coded as ‘SAT4’ resembled with Aeribacillus pallidus in the morphological, biochemical and molecular tests. The production of antibacterial metabolites by SAT4 was optimized. These active metabolites were precipitated by 50% ammonium sulphate and purified through sephadex G-75 gel permeation chromatography and reverse phase HPLC. The molecular weight of 37 kDa was examined by SDS-PAGE. The structural elucidation of the purified product was studied by FTIR, 1H and 13C NMR. The X-ray diffractions study showed that the crystals belonged to the primitive orthorhombic lattice (a = 12.137, b = 13.421, c = 14.097 Å) and 3D structure (proposed name: Aeritracin) was determined. This new peptide antibacterial molecule can get a position in pharmaceutical and biotechnological industrial research.

1. Introduction

Microorganisms make up an everlasting reservoir of chemical compounds with pharmacological, physiological, medical or agricultural uses [45] and many bio active small molecules are synthesized by these naturally populated microbes [21], [10]. The number of bioactive chemical compounds has been reported by bacilli, pseudomonas, actinomycetes and fungi [27]. Among them 800 peptide antibiotics have been described [33] and of this total, 66 various peptide antibiotics are particularized by strains of Bacillus subtilis and 23 are active metabolites of Bacillus brevis [18], [31], [20]. Some of these antibiotics including the polypeptide are being used against the common bacterial targets and thus having the broad spectrum activity. Bacilli producing peptide antibiotics (gramicidins, tyrocidines, and bacitracins) are mainly mesophilic [15]. Few of them are capable of growing at temperatures above 40 °C. They include B. brevis var. G-B, producing gramicidin C [14], and Bacillus polymyxa, producing gavaserin and saltavalin [38]. Aeribacillus pallidus belongs to class Bacilli and its growth occurs at 55–60 °C. Although the progress and speed of new antibiotic discovery has indeed slowed down [51] but in recent years the natural products are the most effective source of drugs and have gained valuable attention for their clinical practices and consistent therapeutic value. Therefore the importance and significance of antibiotics to medicine has led to much research into their discovery and production [29]. Here we describe the production and characterization of a new antibiotic molecule obtained from a newly isolated thermophilic A. pallidus strain SAT4.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Isolation and screening

Thermophilic bacterial strains were isolated from soil sample of Thar Dessert, Pakistan by serial dilution method. Bacterial colonies were purified on nutrient agar medium at 50 °C by standard streaks plate technique. Antibacterial activity of these purified isolates were checked against Micrococcus luteus ATCC 10240, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 49189 and Escherichia coli ATCC 87064 by agar well diffusion assay.

2.2. Characterization

The purified bacterial isolate SAT4 was characterized on the basis of morphological, biochemical and genomic analysis.

2.2.1. Morphological study

The morphological parameters were studied according to Buchanan and Gibbons [8]. For evaluation of colony morphology, under aseptic techniques, the purified and isolated colony was grown on nutrient agar media and was studied for colony morphology (size, pigmentation, form, margin, and elevation), gram’s staining, spore staining and bacterial motility.

2.2.2. Biochemical study

The combination of API 50CHB V4.0 and API 20E kit (BioMerieux SA France; Lot No. 833022401) was used for biochemical analysis according to the manufacturer’s protocol and test results were recorded after 24 h of incubation. The results were analyzed into a bio- Mérieux identification software database (apiweb™; BioMerieux SA).

2.2.3. Molecular study

A 16S rRNA gene sequence to study bacterial phylotypes and taxonomy was used to identify bacterial isolate. DNA was extracted from bacterial cultures using Wizard genomic Kit (Promega, Madison, USA) according to the manufactures’ specifications. DNA concentration in sample was determined using Nanodrop1000 (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, USA) as per standard procedure. PCR amplification and sequencing of 16S rRNA gene was carried out using a Takara 16S rDNA bacterial identification kit. 1 μl of the extracted DNA was amplified with universal primers F27 (5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3′) and R907 (5′-CCGTCAATTCCTTTRAGTTT-3′), generating a PCR product. All reactions were carried out in 0.5 ml PCR tubes, containing 1 μl of each primer, 9.5 μl of sterile distilled water and 12.5 μl of Master Mix (PCR Master Mix 2X, Fermentas, #K0171). PCR was performed in a T-Personal combi PCR machine (Biometra, Germany, #2106284) with the following program: 3 min denaturation at 95 °C, followed by 30 cycles of 1 min denaturation at 94 °C, 1 min annealing at 58 °C, 1 min extension at 72 °C, and a final extension step of 3 min at 72 °C. PCR product of the correct size was purified by JET quick PCR products purification spin/250 kit (GENOMED, Germany). Extracted DNA was visualized by gel electrophoresis on 0.8 % agarose gel and 5 μl of PCR products on 1.5% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide (0.5 mg/ml) in 1× TAE buffer (50× TAE buffer: 242 g/l Tris, 18.61 g/l NaEDTA.2H2O, 57 ml glacial acetic acid). About 1 μl loading dye (30% v/v glycerol, 0.25 % w/v bromophenol blue, 0.25 % w/v xylene cyanol FF) was added to 3 μl of sample and mixed before loading into wells. DNA ladder (Kbp) (Fermentas GeneRulerTM, #SM0313) was used for PCR products. 2 μl of ladder was mixed with 2 μl of loading dye before its loading in the first well of the gel. The gel was run at 80 V for 45 mins. The gel was then observed for bands under UV using gel-dock imaging system (BioRad, Milan Italy).

Sequencing of PCR products was performed and analyzed in both directions using an ABI Prism 310 automated DNA sequencer using BigDye Terminator cycle sequencing kit (PE Applied and Biosystem USA). This kit contained a BigDye Terminator tube, filled with 10 μl of pinkish solution containing 2 μl of primer and 8 μl of BigDye Terminator Reagent. 10 μl of purified PCR product was transferred to this Big Dye Terminator tube. Then samples were sequenced. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) was used to align the obtained bacterial 16S rDNA sequence with thousands of known different available 16S rDNA sequences in this database, and percent homology scores were generated to identify bacteria. Phylogenetic tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method [40] using the MEGA 4.0 software package. Bacteria with 16S rDNA sequences >99% similarity was considered to be of the same phylotype [19].

2.3. Production of antibacterial compound

Shake flask fermentation experiments were carried out for the production of antibacterial metabolites by bacterial isolate SAT4. 100 ml of production medium [9] (l-glutamic acid: 5 gm/l; KH2PO4:0.5 gm/l; K2HPO4:0.5 gm/l; MgSO4:0.2 gm/l; MnSO4:0.01 gm/l; NaCl:0.01 gm/l; FeSO4:0.01 gm/l; CuSO4:0.01 gm/l; CaCl2:0.015; Glucose:1%) was inoculated with 10% of bacterial inoculum and it was incubated at 50 °C in shaking incubator for 24 h at 150 rpm. After 24 h of incubation, sample was centrifuged for 15 min at 10,000 rpm by table top centrifuge to get cell free supernatant and antibacterial activity in the supernatant was analyzed against test bacterial strains by agar well diffusion assay [24], [42].

2.4. Optimization of the production of antibacterial compound

The production of antibacterial compound was optimized by analyzing the time of incubation, pH, temperature, agitation rate, nitrogen, and carbon concentrations. Incubation time was analyzed from 24 to 144 h; pH was studied from 4 (acidic) to 9 (basic); temperature ranged from 45 to 60 °C; the concentration of glutamic acid used as a source of nitrogen varied from 0.25 to 2%; and carbon concentration by taking the glucose from 0.25 to 3%. The optimum levels were confirmed by agar well diffusion assay.

2.5. Purification of antibacterial compound

Precipitation, a method of protein purification [25] was carried out by ammonium sulphate [48], [11]. The culture supernatant was treated with powdered ammonium sulphate (20, 40, 50, and 60% saturation). After sufficient shaking, solution was placed in the cold for one hour and precipitates were collected by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The precipitates were resuspended in 15 ml of 0.05 M potassium phosphate buffer at pH 6. Dialysis was carried out against the same buffer for 24 h in dialyzing bag and the pallets were freeze dried. Further purification was processed by gel permeation chromatography. The column was carefully loaded with 3% sephadex G-75 gel suspended in 0.05 M phosphate buffer. The dialyzed protein sample was eluted at a flow rate of 36 ml/h and fractions (3 ml each) were collected. The absorption of these fractions was measured at 280 nm by UV-spectrophotometer (Agilent USA). The fraction showing antibacterial activity were pooled and lyophilized. The activity of these fractions were tested against indicator bacterial strains by agar well diffusion method. Finally, the purified sample was analyzed by reverse phase HPLC (C18 column; 5 μm; 4.6 mm × 150 mm) using isocratic elution of 20 mM Na2HPO4/130 mM NaCl at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. Polymyxin B was taken as standard peptide antibiotic due to same class of metabolite sample.

2.6. SDS-PAGE analysis

In order to monitor purity, sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed using 12% of resolution gel and 5% of stacking gel [30]. Sample was prepared by dissolving it with equal proportion of sample buffer and loaded onto several wells along with Prestained Protein Ladder (Fermentas, PageRuler, #SM 0671). One-half of the gel was stained with coomassie brilliant blue according to the method of Lee et al. [30] while the other half was assayed directly for antibacterial activity by the modified test [7].

2.7. FTIR and NMR analysis

FTIR spectra of sample were recorded in 3600–650 cm−1 region by Bruker Germany Alpha FT-IR model. The samples for NMR analysis were prepared by dissolving 15 mg of sample in 0.5 ml D2O. NMR spectra were analyzed using Bruker 300 MHz spectrometer equipped with 5 mm of probehead for 1H and 13C analysis.

2.8. X-ray crystallography

Crystals of the lyophilized sample were developed at room temperature. The method involved mixing 2 ml of solvent solution (70% CH3OH) with lyophilized sample (10 mg/ml) in a test tube for 30 h. Diffraction data related to X-ray crystal structure were collected, processed, and calculated from a single crystal source using a STOE-IPDS II equipped with an Oxford Cryostream low-temperature unit, Germany. Structure solution and refinement was done using SIR97, SHELXL97 and WinGX. During data collection, the crystal was maintained at cryogenic temperatures so as to reduce radiation damage.

2.9. Thermostability analysis

Thermostability was evaluated by taking 0.1% aqueous solution of pure compound in four different test tubes, kept them for one hour in water bath at 45, 50, 55, and 60 °C. Agar well diffusion method was used to measure the activity against S. aureus and M. luteus. The antibacterial activity of untreated sample measured at 37 °C was taken as control. Percentage loss of antibacterial activity was calculated using the following formula:

where A0: activity of control, Af: activity after treatment.

3. Results

3.1. Screening of antibacterial producing bacterial species

Five isolates were purified (coded as SAT1 to SAT5) and antibacterial activity of strain “SAT4” showed maximum activity against S. aureus giving zone of inhibition of 25 mm followed by the 22 mm inhibitory zone against M. luteus (Table 1).

Table 1.

Antibacterial activity of selected thermophilic bacterial isolates against indicator bacterial strains.

| Indicator bacterial species | Zone of inhibitions shown by the thermophilic bacterial isolates (mm) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAT1 | SAT2 | SAT3 | SAT4 | SAT5 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 25 | 6 |

| Micrococcus luteus ATCC 10240 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 22 | 6 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 49189 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 1 |

| E. coli ATCC 87064 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

3.2. Characterization

Morphologically bacterial isolate SAT4 was a motile, spore forming and Gram positive rod arranged in pairs and colonies were white to off white in color, circular, flat, with entire margins. 98.4% significant taxon was identified as Geobacillus pallidus strain SAT4 (now known as A. pallidus) [34] when tested through biochemical kits (Table 2). 16S rDNA sequence was amplified using universal primers F27 and R907 generating a PCR product. Analysis of the 16S-rRNA gene sequences using NCBI server, this thermophilic bacterium showed 100% similarity with A. pallidus (accession number: JN986827). The maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree and evolutionary relationship was analyzed (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Taxonomic characterization of bacterial isolates SAT4.

| Test analysis | Types | Features | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopic examination | Gram’s staining | + | |

| Shape | Rods arranged in pairs | ||

| Morphological characteristics | Spore formation | + | |

| Motility | + | ||

| Macroscopic appearance: colony morphology | Color | White to off | |

| Elevation | Flat | ||

| Colony shape | Circular | ||

| Margins | Entire | ||

| Biochemical characteristicsc |

API 50CHB Tests that were positive fora | ||

| GLY GLU FRU MNE MAN SOR MDG NAG AMY ARB ESC SAL CEL SAC TRE LFUC + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + | |||

| API 20E Tests that were positive forb | |||

| ONPG CIT GEL INO RHA ARA + + + + + + | |||

| Significant Taxon 98.4 % Geobacillus pallidus | |||

| Molecular | Universal primers F27 and R907 | ||

| Characteristics | 100% homology with Aeribacillus pallidus at NCBI server (accession number: JN986827) previously known as Geobacillus pallidus[21] | ||

Indications: + sign indicates the positive reaction (color change), GLY: glycerol; GLU: d-glucose; FRU: d-fructose; MNE: d-mannose; MAN: d-mannitol; SOR, MDG, NAG: N-acetylglucosamine; AMY: amygdalin; ARB: arbutin; ESC: esculin ferric citrate; SAL: salicin; CEL: d-cellobiose; SAC: d-sucrose; TRE: trehalose; LFUC: l-fucose.

Only the tests with a positive result are included here (remaining tests were negative).

Only the tests with a positive result are included here (remaining tests were negative). ONPG: 2-nitrophenyl-ß-d-galactopyranoside; CIT: trisodium citrate; GEL: gelatin; INO: inositol; RHA: l-rhamnose; ARA: l-arabinose.

Biochemical tests: API kit system with percentage of positive tests after 24 h of incubation.

Fig. 1.

Evolutionary and phylogenetic relationship of Aeribacillus pallidus SAT4 with 47 taxa (linearized).

3.3. Optimization analysis

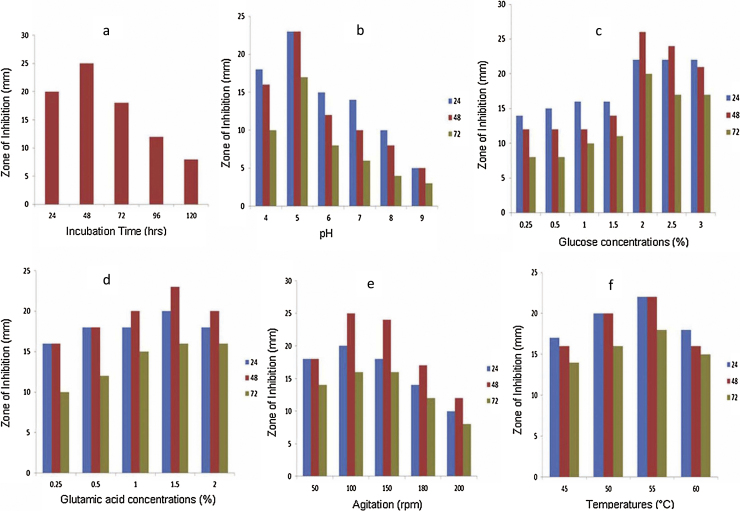

The maximum production of antibacterial metabolites was observed at following parameters: 48 h of incubation, pH 5, 2% glucose, 1.5% glutamic acid, 100 rpm, and 55 °C temperature (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Optimization of antibacterial compound production by Aeribacillus pallidus SAT4 (a) effect of Incubation time (hours) (b) various pH values (c) glucose concentrations, used as carbon source (d) glutamic acid concentrations, used as nitrogen source (e) Effect of agitation (rpm) rates (f) Effect of different temperatures.

3.4. Purification analysis

Antibacterial compound was purified using 50% saturated ammonium sulphate followed by the fractionation through sephadex G-75 gel permeation chromatography and protein concentration were estimated at 280 nm (Supplementary Fig. 1). The retention time of protein sample was 13.109 min when eluted through HPLC at 254 nm as compared to polymyxin as standard protein antibiotic at 11.952 min. These spectral peaks distinctively characterize the peptide antibiotic and differentiate them from other polypeptide antibiotics (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Supplementary material related to this article found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.btre.2015.09.003.

Supplementary Fig. S1 Purification of antibacterial compound from Aeribacillus pallidus SAT4 by Sephadex G-75 column. Column was equilibrated and eluted with phosphate buffer, pH 6.0 at a flow rate of 0.6 ml/min.

Supplementary Fig. S2 HPLC chromatogram of antibacterial compound obtained by Aeribacillus pallidus SAT4 (A) sample and (B) polymyxin B as standard, at different wavelengths.

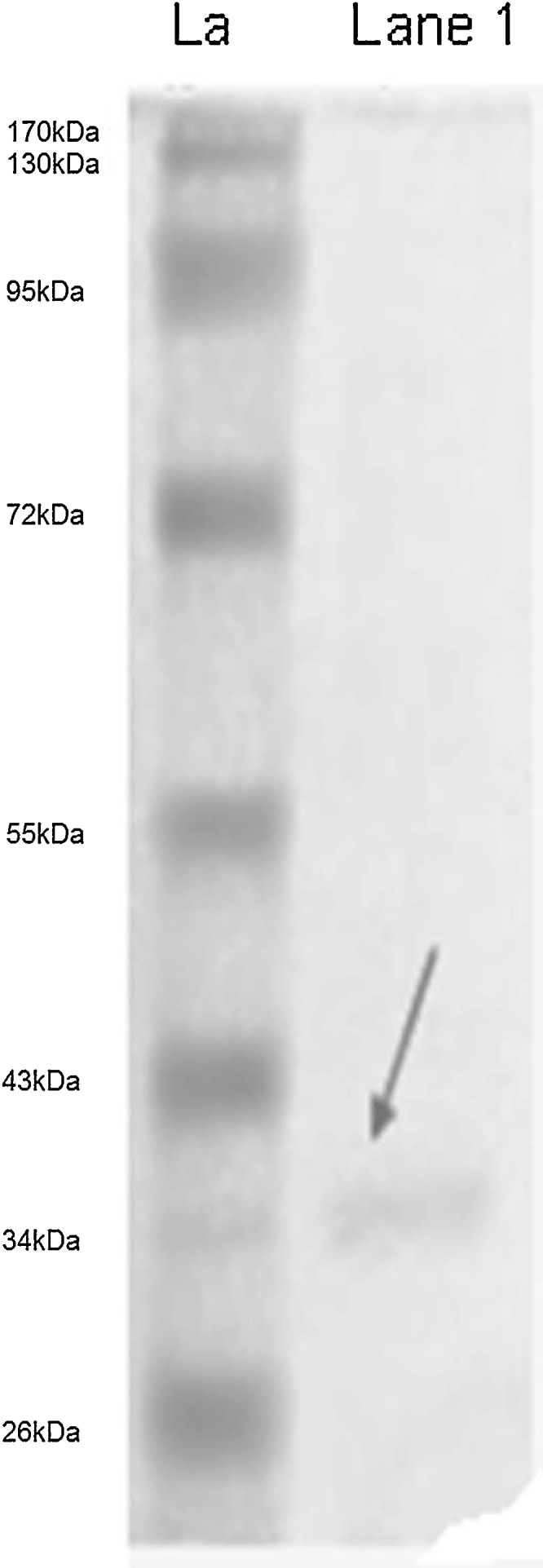

3.5. SDS-PAGE analysis

SDS-PAGE analysis of purified sample revealed single band at 37 kDa (Fig. 3). Zone of inhibition against S. aureus was observed when gel overlay test was performed at 37 °C corresponding to the protein band at the same position.

Fig. 3.

SDS-PAGE analysis (La: Ladder; Lane 1: protein sample).

3.6. FTIR analysis

The spectrum of this ligand exhibited weak bands in the 3400–3100 cm−1 region; while strong bands appeared in the region of 3600–3500 cm−1 may be due to presence of H—O—H (asymmetric vibration). Similarly a band at 2900 cm−1 was observed which belongs to ( C—H) stretching. The strong bands belong to (—C N), and (C O) were found at 2359.86 cm−1. In the spectrum of peptide ligand, other bands at 1700 cm−1, 1540.81 cm−1 and 1257.49 cm−1 were appeared which attributed to asymmetric interaction (O—N—O), (N—H) and (C—O), respectively. The peptide bond formation could also be confirmed due to N—H stretching and C—O in frequency regions of 1540.81 and 1257.49 cm−1, respectively with small contribution of C—N group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Prominent FT-IR bands for antibacterial peptide compound.

| Compound | FT-IR (cm−1) |

|---|---|

| Thermostable peptide antibacterial compound produced by Aeribacillus pallidus SAT4 | 3600–3650 stretching (O—H), 2990–2800 stretching (—C—H sp3), 2359 stretching (—N C O or N C), 1860–1786 (R2C CR2), 1820–1760 (C O), 1540 bending (N—H), 1690 (O C—NH2), 1400–1220 week for (C—O—H), 1600–1475 stretching (C C), 1257 stretching (—C—O—), 1015 (R-COR2-R), 750 bending (—CH2—), 794 (1,3-disubstituted ring), 668 bending (C C, C—X) |

3.7. NMR analysis

The 1H NMR spectrum of sample showed the signals about aliphatic groups. A —CH3 resonance was observed at 1.195 ppm, while —C—CH2—C— (sp3 hydrogen) were recorded at 1.571 ppm. At high dilution, hydroxyl protons (OH) showed absorption near 0.5–1.0 ppm (0.751 ppm), while in concentrated solution their absorbance was closer to 4.5 ppm and it was not observed in the spectrum. The resonance of alkyl amines (RNH2) was observed at 3.996 ppm (Supplementary Fig. 3a). 13C NMR spectra were used to determine the number of nonequivalent carbons and to identify the types of carbon atoms which may be present in the compound. The 13C NMR spectrum of sample demonstrated that saturated carbon CH3, CH2 appeared at 28.190 ppm and 28.738 ppm, respectively. The resonance at 69.69 ppm showed the effects of electronegative atom (—C—O) (Supplementary Fig. 3b).

Supplementary material related to this article found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.btre.2015.09.003.

Supplementary Fig. S3 300 MHz NMR spectrum of antibacterial compound by Aeribacillus pallidus SAT4 dissolved in D2O (a) 1H NMR (b) 13C NMR.

3.8. Structure identification by X-ray crystallography

Antibacterial compound (proposed name: Aeritracin) isolated from A. pallidus SAT4 was subjected to X-ray diffraction study. The geometry of polypeptide contains various amino acids residues (Fig. 4a). The crystal system is triclinic with molecular formula of C55H82N16O17 showing the presence of histidine C27-N28 with bond lengths of (1.32909 Å (1.5)), N28-C29 (1.32989 Å (1.5)), C29-N30 (1.32887 Å (1.5)), N30-C31 (1.33197 Å (1.5)) and C31-C27 (1.38236 Å (1.5)). The selected bond lengths of (1.39026 Å (1.5)) and (1.39138 Å (1.5)) from C38-C43 and C71-C76, respectively showed the presence of two benzene rings. The bond lengths of (1.23148 Å (2)), (1.34144 Å (1)) and (1.55458 Å (1)) exhibited the existence of C O (C9-O1), C—N (C9-N11) and CC (C12-C13), respectively. The crystals belong to the primitive orthorhombic lattice with the cell parameters a = 12.137, b = 13.421, c = 14.097 Å (Fig. 4b). The analytical data (Table 4) and the selected bond lengths are given in Supplementary Table S1.

Fig. 4.

(a) 2D structure [2-(9-((1H-imidazol-4-yl)methyl)-3-(2-amino-2-oxoethyl)-21-(2-(2-amino-4-(2-aminoacetamido)-4-oxobutanamido)-3-phenylpropanamido)-18-(3-aminopropyl)-12-benzyl-15-(sec-butyl)-2,5,8,11,14,17,20-heptaoxo-1,4,7,10,13,16,19-heptaazacyclopentacosan-6-yl) acetic acid] of antibacterial compound (proposed name: Aeritracin) obtained from thermophilic Aeribacillus pallidus SAT4 (b) The 3D crystal structure of antibacterial compound obtained from Aeribacillus pallidus SAT4 belong to the primitive orthorhombic lattice with the cell parameters a = 12.137, b = 13.421, c = 14.097 Å.

Table 4.

Data processing statistics of antibacterial compound obtained by Aeribacillus pallidus SAT4 was identified and calculated from a single crystal source using a STOE-IPDS II equipped with an Oxford Cryostream low-temperature unit Germany.

| Molecular formula | C55 H82 N16 O17 |

| Molecular weight | 1,239.37 |

| Molecular composition | C: 0.533, H: 0.067, N: 0.181, O: 0.219 |

| Crystal system | Triclinic |

| Space group | P-1; Shoenflies: C1-1, a = 12.137, b = 13.421, c = 14.097 |

| Alpha = 84.269 (5) Å | |

| Beta = 81.71 (5) Å | |

| Gamma = 80.86 (5) Å | |

| V = 2116.8 (2) Å3 | |

| Absorption coefficient | 0.34 mm–1 |

| No. of reflections collected/unique | 7955 |

| No. of reflections used [I > 2σ(I)] | 6045 |

| Parameters | 474 |

| Final R indices | R1 = 0.0282, wR2 = 0.0677 |

| R indices (all data) | R1 = 0.0394, wR2 = 0.0750 |

| Structure determination | SIR97, SHELXL97 and WinGX |

| Equipment | STOE-IPDS II equipped with an Oxford Cryostream low-temperature unit |

Supplementary material related to this article found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.btre.2015.09.003.

3.9. Thermostability of the antibacterial compound

Thermostability of cell free supernatant and pure compound was tested at 45, 50, 55, and 60 °C and antibacterial activity was evaluated against S. aureus and M. luteus (indicator strains) by agar well diffusion assay. At 55 °C, 22 and 18 mm inhibitory zones were observed against M. luteus and S. aureus, respectively while activity was reduced at 60 °C (Table 5) while pure antibacterial compound using 0.1% concentration showed 25 and 22 mm inhibitory zones against these indicator strains, respectively at 37 °C. 18 and 20% loss of activity was observed against same strains at 45 °C, respectively.

Table 5.

Thermostability analysis of cell free supernatant and pure antibacterial compound at various temperatures against Micrococcus luteus and Staphylococcus aureus as indicator bacterial strains.

| Sample | Zone of inhibitiona (mm) (before treatment at 37 °C) (A0) |

Temperature (°C) | Activity against M. luteus (Af) |

Activity against S. aureus (Af) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. luteus | S. aureus | Zone of inhibition (mm) | % age loss of activityb | Zone of inhibition (mm) | % age loss of activity* | ||

| Cell free supernatant | 22 | 25 | 45 | 14 | 36 | 12 | 52 |

| 50 | 18 | 18 | 15 | 40 | |||

| 55 | 22 | 0.00 | 18 | 28 | |||

| 60 | 10 | 55 | 8 | 68 | |||

| 45 | 18 | 18 | 20 | 20 | |||

| Analysis after purification | 50 | 15 | 31 | 16 | 36 | ||

| 55 | 12 | 45 | 12 | 52 | |||

| 60 | 8 | 63 | 10 | 60 | |||

Formula: A0 − Af/A0 × 100, where A0: activity control; Af: activity after treatment.

0.1% concentration of purified antibacterial compound produced by Aeribacillus pallidus SAT4 was used before treatment.

4. Discussion

A. pallidus belong to genera Bacilli [51], [6] producing antibacterial molecule against S. aureus, M. luteus, and P. aeruginosa. The bacterial metabolites possessing antimicrobial or antifungal activity including peptides [52] are getting worth now a day and due to number of clinical concerns their usage is important [41], [47]. A. pallidus SAT4, a thermophilic bacterium, produced peptide antibacterial metabolites at 50 °C. In spite of the great attention to microorganisms living under extreme environmental conditions, including thermophiles [2] the secondary metabolism of thermophilic microorganisms is poorly understood and virtually nothing is known of thermophilic bacilli producing antibacterial substances, including peptides. Mostly peptide antibiotics are produced by mesophilic bacterial cultures [15]. Few of them are capable of growing at temperatures above 40 °C. They include B. brevis G-B, producing gramicidin C [14], B. polymyxa in gavaserin and saltavalin [38] and Bacillus licheniformis DSM-13 producing peptide lantibiotics [13]. Bacitracin is a mixture of related cyclic polypeptides with molecular formula of C66H103N17O16S produced by mesophilic bacterial strain B. subtilis. It is broad spectrum antibiotic that disrupt both gram positive and gram negative bacteria by interfering with cell wall and peptidoglycan synthesis [44]. In 2002, Esikova et al. [17] reported the thermophilic Bacillus species strains VK2 and VK21 involved in the production of peptide antibacterial molecules. Streptomyces species SRDP-TK-07 has been reported to produce antibacterial metabolites at 45 °C [39]. Geobacillus toebii HBB-247, a thermophilic bacteria isolated from different thermal spring and soil has been reported for the production of bacteriocin like inhibitory substance which was found to be stable up to 60 °C [37].

Antibiotic synthesis by using producing bacteria varies quantitatively and qualitatively based on the factors including the microbial strains and their growth fermentation conditions [49], [3], [12]. Considering the temperature and agitation rate as critical parameters, optimum production of antibacterial compound by SAT4 was observed at 55 °C and 100 rpm, respectively. During experimentation in the present study, incubation time was evaluated from 24 to 144 h with best activity found at 48 h of incubation and similar observation were recorded by Muaaz et al. [35], who reported that concentration of inhibitory compound was maximum at 48 h by B. subtilis MZ-7. pH was another important aspect of optimization study which was “5” from the experimental values of 4 (acidic) to 9 (basic) and Tang et al. in 1994 [46] reported that variations in fermentation broth pH affect several cellular developments like the regulation and controlling of the biosynthesis of microbial bioactive metabolites [46], [5]. Addition of carbon and nitrogen sources in the production media optimally effect the production of antimicrobial compounds [22]. The optimum concentration of glutamic acid (as a source of nitrogen) and glucose (as source of carbon) was 1.5% and 2%, respectively. In 2006, Nasser discussed that galactose and glucose intensely improved the antibacterial activity of Corynebacterium kutscheri and Corynebacterium xerosis, respectively [9], [36], [23].

In 1991, Shimogki et al. reported that the first step in the purification of the antibacterial was separation of crude antibiotic from the microbial growth followed by precipitation of proteins by 70% ammonium sulfate [43], [1], [26]. The absorbance of protein fractions was observed at 280 nm [50], [32] and electrophoresed [7], [4]. The band on gel appeared at the position of 37 kDa while molecular weight of bacteriocin like substance produced by G. toebii strain HBB-247 was recorded about 38 kDa [37].

1H and 13C NMR spectra showed the presence of alkyl groups, amide linkage and carbonyl groups in the sample at 300 MHz. The resonance of alkyl amines (RNH2) was observed at 3.996 ppm while Epperson and Ming recorded that 1H NMR spectrum of the Co(II) complex of bacitracin mixture with amino acids appeared at 1–12 ppm and found the positions of the protons in the amino acid (α, β, etc.) at 11.7 ppm [16]. The resonance at 69.69 ppm showed the effects of electronegative atom (—C—O) while 13C spectrum reported by Kim et al. showed carbon signal of C O at 218.04 (C-3) and C C at 150.96 (C-20), 109.47 (C-29) [28].

In 2001, Kim et al. reported that the structure of antibacterial compound was found to be orthorhombic which consisted of 3-different sides and three of 90° angle. The bond length of 1.2223 and 1.3639 Å exhibited the presence of C O (C3-O1) and C C (C20-C29), respectively [28].

The thermostability of both cell free supernatant and purified antibacterial compound showed that cell free supernatant was relatively stable at 55 °C showing 0 and 28% loss of activity against M. luteus and S. aureus, respectively. The activity of pure antibacterial compound was decreased 45% against Micrococcus lutes and 52% against S. aureus after treatment at 55 °C [13].

In conclusion, novel peptide antibacterial compound (proposed name: Aeritracin) produced by a thermophilic A. pallidus SAT4 is effective against S. aureus, M. luteus, and P. aeruginosa. This antibiotic would be a new addition in pharmaceutical research and drug development.

Contributor Information

Syed Aun Muhammad, Email: aunmuhammad78@yahoo.com.

Safia Ahmed, Email: safiamrl@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Abdel-Bar N., Harris N.D., Rill R.L. Purification and properties of an antimicrobial substance produced by Lactobacillus bulgaricus. J. Food Sci. 1987;52:411–415. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguilar A. Extremophile research in the European Union: from fundamental aspects to industrial expectations. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1996;18:89–92. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akhurst R.J. Antibiotic activity of Xenorhabdus spp., bacteria symbiotically associated with insect pathogenic nematodes of the families Hetrorhabditidae and Steinernematidae. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1982;128:3061–3065. doi: 10.1099/00221287-128-12-3061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atta H.M., Refaat B.M., El-Waseif A.A. Application of biotechnology for production, purification and characterization of peptide antibiotic produced by probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum, NRRL B-227. Global J. Biotech. Biochem. 2009;4:115–125. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Awais M., Pervez A., Qayyum S., Saleem M. Effects of glucose: incubation period and pH on the production of peptide antibiotics by Bacillus pumilus. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2008;2:114–119. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bae S.S., Lee J.H., Kim S.J. Bacillus alveayuensis sp. nov., a thermophilic bacterium isolated from deep-sea sediments of the Ayu Trough. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2005;55:1211–1215. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63424-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhunia A.K., Johnson M.G. A modified method to directly SDS-PAGE the bacteriocin of Pediococcus acidilactici. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1992;15:5–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1992.tb00721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchanan J.R., Gibbons N.E. 8th ed. The Williams and Wilkins Company; Baltimore: 1974. Bergey’s Manual of Determinative Bacteriology. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bushra J., Hasan F., Hameed A., Ahmed S. Isolation of Bacillus subtilis MH-4 from soil and its potential of polypeptidic antibiotic production. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2007;20:26–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berdy J. Bioactive microbial metabolites. A personal view. J. Antibiot. 2005;58:1–26. doi: 10.1038/ja.2005.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charles P., Devanathan V., Anbu P., Ponnuswamy M.N., Kalaichelvan P.T., Hur B.K. Purification, characterization and crystallization of an extracellular alkaline protease from Aspergillus nidulans HA-10. J. Basic Microbiol. 2008;48:347–352. doi: 10.1002/jobm.200800043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen G., Maxwell P., Dunphy G.B., Webster J.M. Culture conditions for Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus symbionts of entomopathogenic nematodes. Nematologica. 1996;42:124–130. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dischinger J., Josten M., Szekat C., Sahl H.G., Bierbaum G. Production of the novel two-peptide lantibiotic lichenicidin by Bacillus licheniformis DSM 13. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6788. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Egorov N.S. Vestn. Mos. Gos. Univ. Ser. Biol. 1999;4:38–49. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Egorov N.S., et al. Mosk Gos Univ.; Moscow: 1987. Antibiotiki-polipeptidy (Polypeptide Anyibiotics) p. 263. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epperson J.D., Ming L.J. Proton NMR atudies of Co(II) complexes of the peptide antibiotic bacitracin and analogues: insight into structure-activity relationship. Biochemistry. 2000;39:4037–4045. doi: 10.1021/bi991997p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esikova T.Z., Temirov Y.V., Sokolov S.L., Alakhov Y.B. Secondary antimicrobial metabolites produced by Thermophilic Bacillus spp. Strains VK2 and VK21. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2002;38:226–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Falagas M.E., Kasiakou S.K. Colistin: the revival of polymyxins for the management of multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005;40:1333–1341. doi: 10.1086/429323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Felsenstein J. Comparative methods with sampling error and within-species variation: contrasts revisited and revised. Am. Nat. 2008;171:713–725. doi: 10.1086/587525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fiedler-Weiss V.C. Topical minoxidil solution (1% and 5%) in the treatment of Alopecia areata. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1987;16:745–748. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(87)80003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fischbach M.A. Antibiotics from microbes: converging to kill. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2009;12:520–527. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gesheva V., Ivanova V., Gesheva R. Effects of nutrients on the production of AK-111-81 macrolide antibiotic by Streptomyces hygroscopicus. Microbiol. Res. 2005;160:243–248. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hasan F., Khan S., Shah A.A., Hameed A. Production of antibacterial compounds by free and immobilized Bacillus pumilus SAF1. Pak. J. Bot. 2009;41:1499–1510. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holder I.A., Boyce S.T. Agar well diffusion assay testing of bacterial susceptibility to various antimicrobials in concentrations non-toxic for human cells in culture. Burns. 1994;20:426–429. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(94)90035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janson J.C., Ryden L. VCH Publishers, Inc.; New York: 1989. Protein Purification; pp. 10–24. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jimenez-Diaz R., Rios-sanchez R.M., Desmazeaud M., Ruiz-Barba J.L., Piard J.C. Plantaricins S and T: two new bacteriocins produced by Lactobacillus plantarum LPC 10 isolated from a green olive fermentation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993;59:1416–1424. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.5.1416-1424.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kieser T., Bibb M.J., Buttner M.J., Chater K.F., Hopwood D.A. 2nd ed. John Innes Foundation; Norwich, England: 2000. Practical Streptomyces Genetics. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim E.M., Jung H.R., Min T.J. Purification: structure determination and biological activities of 20(29)-lupen-3-one from Daedaleopsis tricolor (Bull. ex Fr.) Bond. et Sing. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2001;22:59–62. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lam K.S. New aspects of natural products in drug discovery. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:279–289. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee C., Levin A., Branton D. Copper staining: a five-minute protein stains for sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 1987;166:303–312. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90579-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li J., Turnidge J., Milne R., Nation R.L., Coulthard K. In vitro pharmacodynamic properties of colistin and colistin methanesulfonate against Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from patients with cystic fibrosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001;45:781–785. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.3.781-785.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li G.G., Liu B.S., Shang Y.J., Yu Z.Q., Zhang R.J. Novel activity evaluation and subsequent partial purification of antimicrobial peptides produced by Bacillus subtilis LFB112. Ann. Microbiol. 2012;62:667–674. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mak P., Wójcik K., Silberring J., Dubin A. Antimicrobial peptides from heme-containing proteins: hemocidins. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2000;77:197–200. doi: 10.1023/a:1002081605784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miñana-Galbis D., Pinzón D.L., Lorén J.G., Manresa A., Oliart-Ros R.M. Reclassification of Geobacillus pallidus (Scholz et al., 1988) Banat et al., 2004 as Aeribacillus pallidus gen. nov., comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2010;60:1600–1604. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.003699-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muaaz M.A., Sheikh M.A., Ahmad Z., Hasnain S. Production of surfactin from Bacillus subtilis MZ-7 grown on pharma media commercial medium. Microb. Cell Fact. 2007;10:6–17. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-6-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nasser M. Effect of carbon source on the antimicrobial activity of Corynebacterium kutscheri and Corynebacterium xerosis. Afr. J. Biotech. 2006;5:833–835. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ozdemir G.B., Biyik H.H. Isolation and characterization of a bacteriocin-like substance produced by Geobacillus toebii strain HBB-247. Ann. Microbiol. 2012;62:667–674. doi: 10.1007/s12088-011-0227-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pichard B., Larue J.P., Thouvenot D. Gavaserin and saltavalin, new peptide antibiotics produced by Bacillus polymyxa. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1995;133:215–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rakesh K.N., Dileep N., Junaid S., Prashith K.T.R. Optimization of culture conditions for production of antibacterial metabolite by bioactive Streptomyces species srdp-tk-07. Int. J. Adv. Pharm. Sci. 2014;5:1809–1816. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saitou N., Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schallmey M., Sing A., Ward O.P. Developments in the use of Bacillus specie for industrial production. Can. J. Microbial. 2004;50:1–17. doi: 10.1139/w03-076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sen S., Sahu N.P., Mahato S.B. Pentacyclic triterpenoids from Mimusops elengi. Phytochemistry. 1995;38:205–207. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimogki H., Takeuchi K., Nishino T., Ohdera M., Kudo T., Ohba K., Iwnma M., Irie M. Purification and properties of a novel surface active agent and alkaline resistant protease from Bacillus sp. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1991;55:2251–2258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smack D.P., Harrington A.C., Dunn C., Howard R.S., Szkutnik A.J., Krivda S.J., Caldwell J.B., James W.D. Infection and allergy incidence in ambulatory surgery patients using white petrolatum vs bacitracin ointment. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1996;276:972–977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith N.K., Gilmour S.G., Rastall R.A. Statistical optimization of enzymatic synthesis of derivatives of trehalose and sucrose. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 1997;21:49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tang L., Zhang Y.X., Hutchinson C.R. Amino acids catabolism and antibiotic synthesis: valine is source for precursors for macrolide biosynthesis in Streptomyces ambofaciens and Streptomyces fradiae. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:6107–6119. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.19.6107-6119.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tripathi C.K.M., Praveen V., Singh V., Bihari V. Production of antibacterial and antifungal metabolites by Streptomyces violaceusniger and media optimization studies for the maximum metabolite production. Med. Chem. Res. 2004;13:790–799. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wingfield P. Protein precipitation using ammonium sulfate. Curr. Prot. Protein Sci. 2001 doi: 10.1002/0471140864.psa03fs13. Appendix 3: Appendix 3F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Webster J.M., Chen G., Hu K., Li J. In: Entomopathogenic Nematology. Gaugler R., editor. Wallingford: CAB International; 2002. Bacterial metabolites; pp. 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamamoto Y., Togawa Y., Shimosaka M., Okazaki M. Purification and characterization of a novel bacteriocin produced by Enterococcus faecalis strain RJ-11. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69:5746–5753. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.10.5746-5753.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yasawong M., Areekit S., Pakpitchareon A., Santiwatanakul S., Chansiri K. Characterization of thermophilic halotolerant Aeribacillus pallidus TD1 from Tao dam hot spring, Thailand. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011;12:5294–5303. doi: 10.3390/ijms12085294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zuber P.A., Marahiel M.A. In: Biotechnology of Antibiotics. Strohl W., editor. Marcel Dekker; New York: 1997. pp. 187–216. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig. S1 Purification of antibacterial compound from Aeribacillus pallidus SAT4 by Sephadex G-75 column. Column was equilibrated and eluted with phosphate buffer, pH 6.0 at a flow rate of 0.6 ml/min.

Supplementary Fig. S2 HPLC chromatogram of antibacterial compound obtained by Aeribacillus pallidus SAT4 (A) sample and (B) polymyxin B as standard, at different wavelengths.

Supplementary Fig. S3 300 MHz NMR spectrum of antibacterial compound by Aeribacillus pallidus SAT4 dissolved in D2O (a) 1H NMR (b) 13C NMR.