Abstract

Introduction: Much attention has been paid to the idea of cell therapy using stem cells from different sources of the body. Fat-derived stem cells that are called adipose derived stem cells (ADSCs) from stromal vascular fraction (SVF) are the subject of many studies in several cell therapy clinical trials. Despite production of some GMP-grade enzymes to isolate SVF for clinical trials, there are critical conditions like inconsistency in lot-to-lot enzyme activity, endotoxin residues, other protease activities and cleavage of some cell surface markers which significantly narrow the options. So we decided to develop a new method via sonication cavitation to homogenize fat tissue and disrupt partially adipose cells to obtain SVF and finally ADSCs at a minimum of time and expenses.

Methods: The fat tissue was chopped in a sterile condition by a blender mixer and then sonicated for 2 s before centrifugation. The next steps were performed as the regular methods of SVF harvesting, and then it was characterized using flow cytometry.

Results: Analysis of the surface markers of the cells revealed similar sets of surface antigens. The cells showed slightly high expression of CD34, CD73 and CD105. The differentiation capacity of these cells indicates that multipotent properties of the cells are not compromised after sonication. But we had the less osteogenic potential of cells when compared with the enzymatic method.

Conclusion: The current protocol based on the sonication-mediated cavitation is a rapid, safe and cost-effective method, which is proposed for isolation of SVF and of course ADSCs cultures in a large scale for the clinical trials or therapeutic purposes.

Keywords: Adipose derived Stem cells, Aesthetics, Cell Therapy, Sonication, Stromal Vascular Fraction

Introduction

To date, the cell therapy notion using isolated stem cells from various parts of the body with different potencies has received a lot of attention. Fat-derived stem cells, the so-called adipose derived stem cells (ADSCs), represent a type of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) that are more abundant in adults in contrast to bone marrow MSC.1 These cells are among the clinically feasible and promising candidates for the autologous cell therapy, in large part due to their pluripotency, immunomodulatory properties, and paracrine effects or secretory activities.2 Therefore, ADSCs are subjects of a number of investigations in several cell therapy clinical trials worldwide. To get a stromal vascular fraction (SVF) and ADSCs from fat tissues, the most efficient method is the dissociation of a lipoaspirate. There are two major techniques generally used to isolate SVF, including: (i) enzymatic and (ii) and mechanical methods. There are a number of mechanical approaches for increasing the density of SVF cells that are based upon washing steps, vibration and shaking procedures and centrifugation, which can favor the release of SVF cells from the adipose tissue.3-8

The therapeutic potential of ADSCs has motivated biotech companies to develop automated processing devices for the preparation of ADSCs. Nowadays, there are many different products in the market that are utilized for fat tissue dissociation such as collagenase (from Clostridium histolyticum), trypsin, clostripain or dispase. A large number of preclinical studies have shown that dissociation of fat tissue with enzymes results in extraction of viable and proliferative ADSCs.9,10 Most of these enzymes are suitable for preclinical studies and there are some good manufacturing practice (GMP)-grade products developed for clinical trials, however some certain critical conditions in clinical trials have significantly narrowed these options. Further, there may be some variations like inconsistency in lot-to-lot enzyme activity, endotoxin residues and other protease activities that raise safety concerns for their uses in clinical trials or even in clinics.

Having compared mechanical and enzymatic methods for the isolation of chondrocytes, there exist some data that show a decrease in cell viability and also remodeled differentiated phenotype in the enzymatic processed tissue.11 In addition, an interesting study showed that collagenase and dispase enzymes could destruct some surface biomarkers on the mononuclear cells.12 Another study demonstrated significantly greater osteogenic differentiation upon use of trypsin, which is a clear indicative for impacts of designated enzymes on induction of different cellular properties.13 Thus, development of non-enzymatic methods may resolve these issues. Here, we developed a new method based on sonication-mediated cavitation to homogenize fat tissue and disrupt adipose cells partially to obtain SVF and finally ADSCs in a short period of and at a low cost.

Materials and methods

Isolation of cells by enzymatic process

Fat tissues were obtained from subcutaneous adipose tissues derived from aesthetic liposuctions. As described previously,14 after 5 times of washing steps with phosphate buffered saline (PBS; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) the tissue samples were incubated at 37°C for 45 min in Dulbecco’s modified essential medium (DMEM; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) containing 2 mg/mL of collagenase (Worthington Biochemical Corp., Lakewood, NJ, USA) with shaking at 60 cycles/min. After centrifugation, the lipid layer was thrown away and the SVF was collected, washed and resuspended in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 100 units/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) and seeded into the tissue culture flask (Orange Scientific, Braine-l’Alleud, Belgium). Twenty four-hour post-seeding, the non-adherent cells were discarded by changing the medium, and the cells were harvested and expanded at 50% confluency.

Isolation of cells by sonication cavitation process

After PBS washing, the sample tissues were dissected in a blender mixer (National Blender, Japan) for 10 s and the processed tissue was mixed by FBS and went under sonication cavitation (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA; 50 W) only for 2 min at 18 MHz for further homogenization and disruption of adipose cells that are more sensitive than stromal cells to the sonication-mediated cavitation. Then, the sample was centrifuged for 10 min at 900 g, the floated lipid was discarded and the pellet was resuspended with 150 mM ammonium chloride (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) for 5 min to lyse RBCs. After 5 min centrifugation at 400 g, the pellets were collected, washed and resuspended in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS as mentioned previously, and then seeded into a T25 culture flask. After 24 h, again the non-adherent cells were removed by changing the medium and the adherent cells were used for further confirmation tests.

Analysis of SVF composition by flow cytometry

The SVFs harvested by both methods were suspended in PBS and then incubated for 30 min at 4°C with the antibodies conjugated with FITC against CD34, CD44, CD73, CD90 and CD105 biomarkers.15 Flow cytometry analyses were performed using a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) located at Iranian Blood Transfusion Organization. Acquired data were then analyzed by utilizing the Win-MDI software.

Analysis of the adipogenic potential of the ADSCs

The differentiation of ADSCs into adipocytes has been described previously.16 Briefly, ADSCs derived by both isolation protocols were cultivated at a seeding density of 2 × 104 cells/well in 12-well plates containing DMEM supplemented with antibiotic and 10% FBS for 24 h. The medium was then changed into differentiation medium consisting of DMEM supplemented with 60 µM biotin, 250 µM IBMX (3 Isobutyl Methyl Xanthin), 1 µM dexamethasone, 35 µM Calcium D-panthothenate, 5 µM indomethacin and also 0.2 µM insulin (all from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA). The cells were preserved in this medium for 3 days and then cultured in the adipocyte maintenance medium consisting of 60 µM biotin, 1 µM dexamethasone, 35 µM d-panthothenate and 0.2 µM insulin for 9 days with medium replacement every 3 days. The adipogenic potential was proved by the Oil Red method,17 which stains intracellular triglyceride droplets. After the differentiation period, the cells were fixed with 10% formalin (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and then incubated for 15 min with the Oil Red solution. Thereafter, the cells were washed 3 times with dH2O and the dye was eluted from cells using isopropanol. The cells were visualized under inverted microscopy.

Analysis of the osteogenic potential of the ADSCs

The differentiation of ADSCs into osteoblasts has been described previously.18 Briefly, ADSCs was seeded into the wells of plates with DMEM supplemented with antibiotic and 10% FBS and allowed to reach 80% of confluency. Then the medium was changed with DMEM supplemented with 10 µg/mL ascorbic acid, 0.1 µM of dexamethasone and also 5 mM of glycerol phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA). The cells were cultured into this differentiation medium for two weeks and replenished with fresh media every 3 days. The osteogenic potential of ADSCs was proved by Alizarin Red staining.19 After two weeks of the osteogenic treatment, the cells were fixed with 10% paraformaldehyde and then incubated for 5 min with Alizarin Red (2% solution). The stained cells were washed 3 times with dH2O and then photographed under inverted microscopy.

Analysis of the chondrogenic potential of the ADSCs

The differentiation of ADSCs into chondrocytes has been described previously.20 Briefly, at 80% confluency of ADSCs in 12 well plates, the medium was changed by chondrogenic medium. This medium consisting of 6.2 µg insulin, 50 nM ascorbic acid, proline and 10 ng/mL transforming growth factor β3 was replaced every 3 days for up to 3 weeks. After the differentiation process, the pellets were fixed with 10% paraformaldehyde and stained with Alcian blue and visualized morphologically under inverted microscopy.

Statistical analysis of the data

The statistical comparison was performed using independent samples t test. The p values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

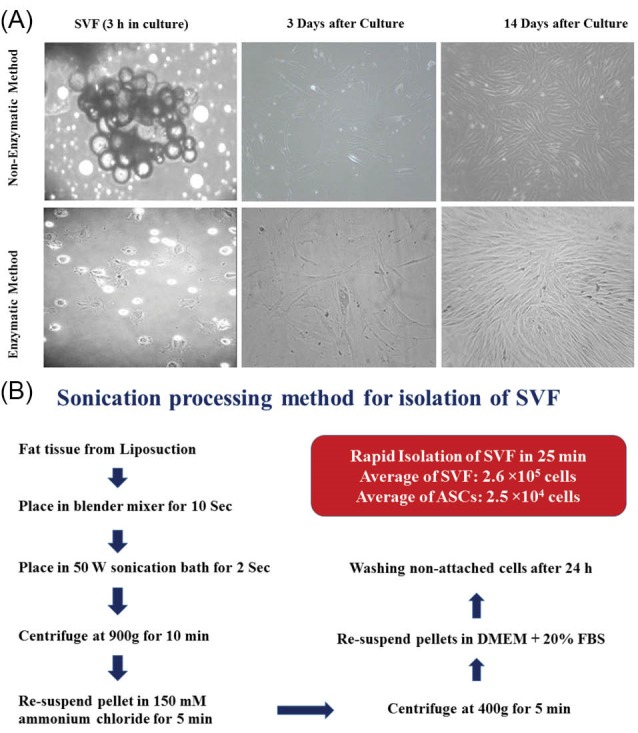

Isolation of SVF and culture of ADSCs

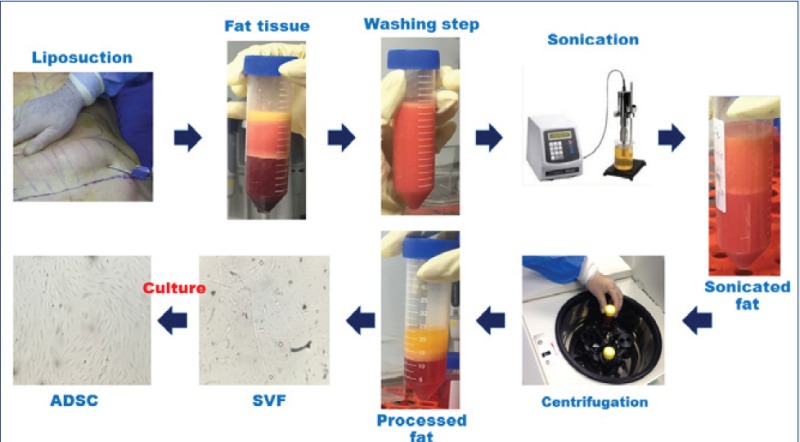

As demonstrated in Fig. 1A, there are many adherent ADSCs easily isolated from the fat tissue without application of collagenase. This rapid method only requires less than 30 min to complete and just uses standard culture materials and equipment. Fig. 1A shows that sonication as well as collagenase is very efficient to release collagen fibers that firmly attach fat tissue cells together. After two weeks of cultivation of these cells, quite similar cells were observed in the flasks. The isolation steps in details are presented in Fig. 1B.

Fig. 1 .

Comparison of isolated SVFs by sonication and enzymatic methods. Small particles of adipose tissue are seen in the culture plate immediately after isolation. On day 3 post culture, mesenchymal cells just attached in the flask that started to proliferate with a considerable rate at two weeks after culture (panel A). A schematic diagram that shows our isolation process and the results in brief (panel B).

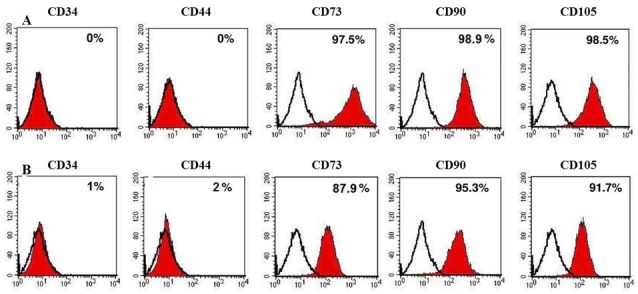

Flow cytometric characteristics of SVF samples

The plot of flow cytometer revealed two general populations of cells that are present in the fraction of the SVF output as shown in Figs. 2A and B. Analyzing the surface markers that flow cytometry expressed for SVF from both processing methods showed similar sets of surface antigens, and a slightly more CD34, CD73 and CD105 expressing cells were seen (Figs. 2A and B). The comparison between these two methods shows no significant difference, and therefore the cells isolated using sonication method show almost the same characteristics as the traditional enzymatic method. The difference in phenotype analysis may reflect differences in rate of growth of the cells in culture. Also the number of viable cells (2.6× 105 cells from 1 mL of fat tissue) are slightly more in the experiments performed by our new method (Fig. 2C). Live ADSCs isolated ranged from 0.0 to 5.0 × 104 cells/g tissue, averaging 2.5 × 104 cells/g tissue (data not shown).

Fig. 2 .

Immuno-flow cytometric analysis of stromal vascular fraction. SVF isolated by the sonication-mediated cavitation process (panel A) and the classical enzymatic (panel B) methods. The number of viable cells demonstrated by flow cytometry for comparison between both processing methods.

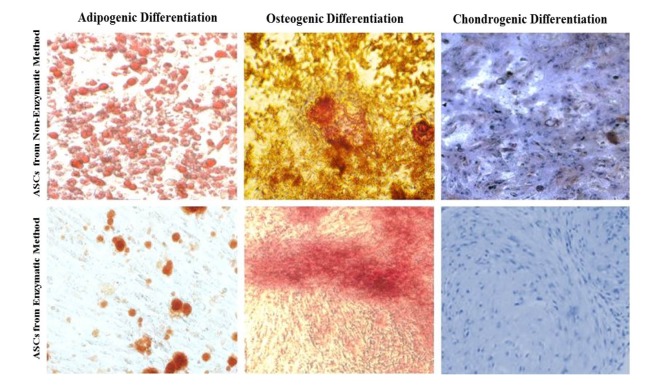

Differentiation potential of ADSCs derived from both methods

To determine the potency of isolated ADSCs, they were further cultured in differentiation media that were specific for adipocyte, osteocyte and chondrocyte differentiation. The Oil Red O, Alizarin Red and Alcian blue staining revealed that the cells isolated by non-enzymatic and classical enzymatic methods could differentiate into the three main lineages (Fig. 3). As shown in Fig. 3, the adipocytes differentiation of ADSCs isolated by two methods did not show significant differences in the level of lipid content. We observed more osteogenic potency of cells isolated by enzymatic method. The chondrogenic potential of both cells was the same. It is obvious that the ADSCs isolated by sonication method has the in vitro criteria for mesenchymal stem cells.

Fig. 3 .

Characterization of ADSC differentiation. Differentiation of ADSCs derived from SVF isolated with sonication rapid process and classical enzymatic method to adipocyte, chondrocyte and osteoblast lineages.

Discussion

In this study, we developed a new rapid protocol for isolation of SVF from fat tissue by the sonication-mediated cavitation method that is an enzymatic digestion free approach. So far, much attention has been paid to the adipose derived mesenchymal stem cells because these cells are able (a) to secret many important cytokines, (b) to impose immunomodulatory effects, (c) to decrease inflammation and (d) to have therapeutic applications (there are about 500 clinical trials with ADSCs up to May 2016; viewed at clinicaltrials.gov). For the US food and drug administration (FDA), the major regulatory affair related to the isolation of SVF is the minimal manipulation. Hence, the FDA published a set of draft guidances for the industry handling with the minimal manipulation and similar utilization of adipose tissue.21,22 In these FDA guidances, it has been mentioned that the isolation of SVF, results in a final product which is “more than minimally manipulated” because the initial architecture of the tissue has been seriously changed. Furthermore, the application of enzymes such as collagenase, dispase or trypsin is considered more than a “minimal manipulation” because the nature of these products are not in full accord with sterilizing, preserving, and storing processes. Therefore, this matter has very serious implications for the clinical use of ADSCs and SVF-based therapies.

Collagenase-based enzymatic methods yield about 1.0 × 105 to 1.0 × 106 nucleated cells/mL from fat processed tissues.8 This is much more than statistics reported by mechanical methods which have reported yields in the range of 1.0 × 104 to 2.5 × 104 nucleated cells/mL of lipoaspirate.3-6 Our data show the isolation of 2.6 ×104 viable nucleated cells/mL of lipoaspirate that is slightly higher than that of the enzymatic method (Fig. 2C). This amount is equal to the Sepax Technology from BioSafe America that is an enzymatic, automated and closed system. At beginning, this device was commercialized for the bone marrow, cord blood, and peripheral blood processing to obtain mononuclear cells (MNCs), but it has recently been used also for the isolation of fat tissues too.23 Furthermore, the content of the recovered mixture of cells via only a centrifugation process and other mechanical isolation approaches has a greater number of peripheral blood MNCs and a subordinate frequency of progenitor cells.

As for the mechanical approaches, there are between 1%-5% ADSCs composition of SVF.3-5 Comparably, our method shows about 10% ADSCs in the SVF. In 2008, Lopez et al described the decreased viability and also transformed differentiation phenotype in the enzymatic groups.11 Another fascinating study conducted by Abuzakouk et al in 1996 demonstrated that collagenase and dispase could destroy some of the surface biomarkers on MNCs.12

On the other hand, tissue dissociation enzymes for use in the fat tissue digestion are very costly, and require potentially thousands of dollars depending on the load of tissues being processed. In a laboratory scale, when the count of progenitor cells is not so relevant (in particular when the cells undergo the culture process), the non-enzymatic method can provide a cost-effective and rapid substitute with minimal manipulation that is closer to the GMP conditions.

Besides, the differentiation potential of the isolated cells into the adipocytes, osteoblasts and chondrocytes were seen in response to induction of media, showing similar patterns of surface markers (Figs. 2A, 2B). The differentiation responses were detected in the cells isolated by sonication and enzymatic methods (Fig. 3). All these suggest that multipotent properties and differentiation capacity of the cells are not compromised after the sonication process. Nonetheless, the data show more osteogenic potential of cells that harvested by enzymatic method. It should be alos noted that Markarian et al3, in 2014, compared nine different approaches to isolate ADSCs. They did not see any significant difference in the proliferation or growth rate of these isolates such as doubling time, but there was a greater potential of osteogenesis in ADSCs when trypsin was used instead of collagenase. This finding clearly demonstrates that different enzymes may result in different cellular properties and hence cellular fates. In our study, we observed less osteogenic potential of ADSCs derived by the sonication method as compared to the collagenase treated cells.

Conclusion

Based on our findings, we believe that the sonication-mediated cavitation method may offer a rapid, safe and cost-effective approach for the isolation of SVF and ADSCs in a large scale. The resultant cells can be used for clinical trials or therapeutic purposes. As a result, we propose this method of isolation for laboratories and even clinics as an alternative strategy that possess less limitations in comparison with the enzymatic protocols.

Competing interests

No conflict of interest to be declared.

Ethical approval

All the experiments were performed according to the guideline provided by the Ethical Committee at Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Research Highlights

What is current knowledge?

√ There are some routinely used enzymatic methods and some mechanical protocols to obtain ADSCs.

√ In enzymatic method, the yield of SVF is about 2.0×105 total nucleated cell/mL.

√ In regular enzymatic methods, the isolated ADSCs tend to differentiate into osteoblasts.

√ The enzymes used in the isolation of ADSCs process are expensive and often not safe.

What is new here?

√ Here, we developed a new rapid, non-enzymatic protocol for the isolation of SVF from fat tissue and less osteogenic potential of ADSCs. We have isolated 2.6 × 105 viable nucleated cells/mL of lipoaspirate that is slightly higher than that of the enzymatic method.

√ The sonication-mediated cavitation protocol is a rapid, safe and cost-effective approach for the isolation of SVF and of course ADSCs in a large scale.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported financially by Iranian Council for Development of Stem cell Sciences and Technologies and in part by the Tehran University of Medical Sciences. We would like to thank Mr. Ahmadreza Shoa Hasani for his helpful comments.

References

- 1.Salibian AA, Widgerow AD, Abrouk M, Evans GR. Stem cells in plastic surgery: A review of current clinical and translational ap plications. Arch Plast Surg. 2013;40:666–75. doi: 10.5999/aps.2013.40.6.666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strioga M, Viswanathan S, Darinskas A, Slaby O, Michalek J. Same or not the same? Comparison of adipose tissuederived versus bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem and stromal cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:2724–52. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Markarian CF, Frey GZ, Silveira MD, Chem EM, Milani AR, Ely PB. et al. Isolation of adipose-derived stem cells: a comparison among different methods. Biotechnol Lett. 2014;36:693–702. doi: 10.1007/s10529-013-1425-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conde-Green A, Slezak S. Enzymatic digestion and mechanical processing of aspirated adipose tissue. Plast Recons Surg. 2014;134:54. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raposio E, Caruana G, Bonomini S, Libondi G. A novel and effective strategy for the isolation of adipose-derived stem cells: minimally manipulated adipose-derived stem cells for more rapid and safe stem cell therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133:1406–9. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah FS, Wu X, Dietrich M, Rood J, Gimble JM. A non-enzymatic method for isolating human adipose-derived stromal stem cells. Cytotherapy. 2013;15:979–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baptista LS, do Amaral RJ, Carias RB, Aniceto M, Claudio-da-Silva C, Borojevic R. An alternative method for the isolation of mesenchymal stromal cells derived from lipoaspirate samples. Cytotherapy. 2009;11:706–15. doi: 10.3109/14653240902981144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doi K, Tanaka S, Iida H, Eto H, Kato H, Aoi N. et al. Stromal vascular fraction isolated from lipo-aspirates using an automated processing system: bench and bed analysis. J Tiss Eng and Regen Med. 2013;7:864–70. doi: 10.1002/term.1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Traktuev DO, Merfeld-Clauss S, Li J, Kolonin M, Arap W, Pasqualini R. et al. A population of multipotent CD34-positive adipose stromal cells share pericyte and mesenchymal surface markers, reside in a periendothelial location, and stabilize endothelial networks. Circ Res. 2008;102:77–85. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.159475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bourin P, Bunnell BA, Casteilla L, Dominici M, Katz AJ, March KL. et al. Stromal cells from the adipose tissue-derived stromal vascular fraction and culture expanded adipose tissue-derived stromal/stem cells: a joint statement of the International Federation for Adipose Therapeutics and Science (IFATS) and the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) Cytotherapy. 2013;15:641–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.López C, Ajenjo N, Muñoz-Alonso MJ, Farde P, León J, Gómez-Cimiano J. et al. Determination of viability of human cartilage allografts by a rapid and quantitative method not requiring cartilage digestion. Cell transplant. 2008;17:859–64. doi: 10.3727/096368908786516783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abuzakouk M, Feighery C, O’Farrelly C. Collagenase and Dispase enzymes disrupt lymphocyte surface molecules. J Immunol Methods. 1996;194:211–6. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(96)00038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pilgaard L, Lund P, Rasmussen JG, Fink T, Zachar V. Comparative analysis of highly defined proteases for the isolation of adipose tissue-derived stem cells. Regen Med. 2008;3:705–15. doi: 10.2217/17460751.3.5.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aust L, Devlin B, Foster SJ, Halvorsen YD, Hicok K, du Laney T. et al. Yield of human adipose-derived adult stem cells from liposuction aspirates. Cytotherapy. 2004;6:7–14. doi: 10.1080/14653240310004539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noureddini M, Verdi J, Mortazavi-Tabatabaei SA, Sharif S, Azimi A, Keyhanvar P. et al. Human endometrial stem cell neurogenesis in response to NGF and bFGF. Cell Biol Int. 2012;36:961–6. doi: 10.1042/CBI20110610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghorbani A, Jalili SA, Varedi M. Isolation of adipose tissue mesenchymal stem cells without tissue destruction: a non-enzymatic method. Tissue Cell. 2014;46:54–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aguena M FR, Tissiani LA, Ishiy FA, Atique R, Alonso N. et al. Optimization of parameters for a more efficient use of adipose derived stem cells in regenerative medicine therapies. Stem Cells Int. 2012;2012:303610. doi: 10.1155/2012/303610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birmingham E, Niebur GL, McHugh PE, Shaw G, Barry FP, McNamara LM. Osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells is regulated by osteocyte and osteoblast cells in a simplified bone niche. Eur Cell Mater. 2012;23:13–27. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v023a02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norgaard R, Kassem M, Rattan SI. Heat shock-induced enhancement of osteoblastic differentiation of hTERT-immortalized mesenchymal stem cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1067:443–7. doi: 10.1196/annals.1354.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mackay AM, Beck SC, Murphy JM, Barry FP, Chichester CO, Pittenger MF. Chondrogenic differentiation of cultured human mesenchymal stem cells from marrow. Tissue Eng. 1998;4:415–28. doi: 10.1089/ten.1998.4.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Minimal Manipulation of Human Cells, Tissues, and Cellular and Tissue-Based Products. Draft Guidance for industry and food and drug administration staff; 2014.

- 22. FDA. Human Cells, Tissues, and Cellular and Tissue-Based Products (HCT/Ps) from Adipose Tissue: Regulatory Considerations. Draft Guidance for industry and food and drug administration staff; 2014.

- 23. Sepax 2. Biosafe Group SA. http://www.biosafe.ch/?portfolio=sepax2. 2015.