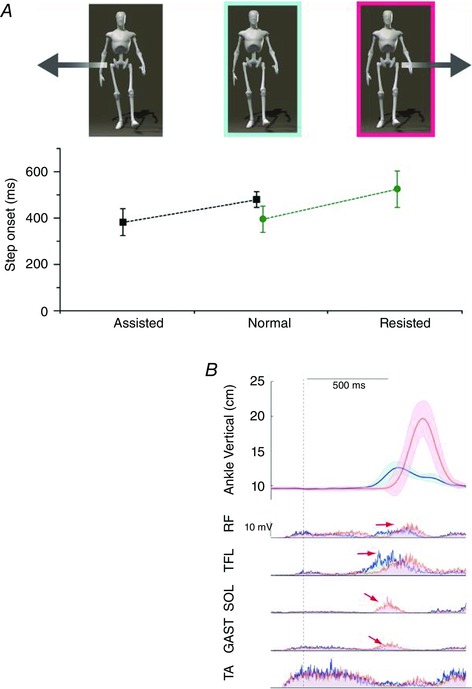

Figure 2. Posture and locomotion coupling during voluntary stepping .

A, during voluntary stepping, single limb stance support is normally achieved prior to stepping. If anticipatory postural adjustments (APAs) are unexpectedly modified by external assistance (data presented in black, group mean and SD of 8 older subjects; adapted from Mille et al. 2007) or resistance (data presented in green, group mean and SD of 12 young women; adapted from Mille et al. 2014), step onset timing is then either advanced (Assisted) or delayed (Resisted) compared with the control condition (Normal) so that step onset occurs when the estimated conditions for stability are achieved. When APAs are assisted, older individuals initiated volitional stepping as fast as younger adults’ performance in the unassisted baseline condition. B, the averaged time profiles from a representative younger adult during baseline rapid step initiation (in blue, average of 10 trials) and during mechanically resisted step initiation (in red, average of 15 trials). All records were synchronized with the onset of the net CoP displacement (vertical dotted line) at time zero. The shaded regions represent ± 1 SD. The vertical displacement of the stepping ankle marker indicates a delay in the first step onset time and increased step height. The mean EMG activity of stepping leg muscles shows a delay of the step motor command (illustrated by the rectus femoris (RF) and the tensor fasciae latae (TFL) activity), and a modification of the step motor command with the appearance of a phasic activation bursts in soleus (SOL) and gastrocnemius medialis (GAST) when a postural perturbation is randomly applied, whereas no modification in the onset of the tiabialis anterior (TA) activity was observed.