BACKGROUND

Standing-level falls are the leading cause of traumatic mortality in senior citizens. Emergency physicians are expected to screen for fall risk and provide preventive measures for patients at high risk;1 recent guidelines indicate that all adult emergency departments (EDs) should be performing this function.2 One key challenge to evidence-based fall risk stratification of older adults is uncertainty about which risk factors or assessment instrument to use.3

Article Summary

The study by Carpenter et al.4 is a systematic review and meta-analysis of published manuscripts and unpublished abstracts of ED-based studies of community-dwelling adults aged 65 years and older. Study inclusion criteria included recruitment of patients of this age in the ED for a fall- or non–fall-related evaluation with sufficient detail provided to reconstruct 2 × 2 contingency tables. The primary objective was to quantify the prognostic sensitivity, specificity, and likelihood ratios of all fall risk factors and stratification instruments to predict falls in the 6 months following an ED visit. With the assistance of a medical librarian experienced in systematic review methodology, the authors conducted a structured search of seven electronic databases, along with a hand-search for research abstracts in Academic Emergency Medicine (AEM) and Annals of Emergency Medicine. Only three ED-based studies met inclusion criteria. Three studies totaling 767 patients derived and evaluated three fall risk prediction instruments. Two studies (660 patients) were prospective and the other was retrospective. The authors performed meta-analysis using a random-effects model when more than one study assessed the same fall risk factor using comparable thresholds and similar fall outcomes at the same follow-up interval.

Quality Assessment

The systematic review adhered to the Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) statement and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Individual study quality was assessed using the Quality Assessment Tool for Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2). All of the studies failed to describe explicit blinding of outcome assessors to the index tests, which increased the risk of incorporation bias. In addition, each study used self-reported falls as the primary outcome measure, but used different definitions of “fall” and different methods of ascertaining falls during the follow-up period, which increases the possibility of uncertain reproducibility. None of the studies referenced or used the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) criteria.

Key Results

The two prospective studies assessed 29 individual predictors. The 6-month incidence of falls was 31% for those initially evaluated in the ED for fall-related complaints and 14% for those evaluated for anything else. Most (62%) post-ED falls resulted in injuries. In general a useful predictor to identify a high-risk individual would have a positive likelihood ratio of 10, while a useful test to identify a low-risk individual would have a negative likelihood ratio less than 0.1.5 None of the individual fall risk factors accurately predicted falls at 6 months using these thresholds. For example, based on one study the most useful positive test was the presence of depression with a positive likelihood ratio of 6.55 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.41 to 30.48), but the meta-analysis likelihood ratio estimate was 2.54 (95% CI = 1.62 to 3.98). Similarly, none of the fall risk factors significantly reduced the probability of post-ED falls since the lowest negative likelihood ratio, for cutting one’s own toenails, was 0.57 (95% CI = 0.38 to 0.86).

Two fall risk prediction instruments were described: the Tiedemann and the Carpenter scores. Both are simple scores based upon two to four fall risk factors. A Tiedemann score of 3 demonstrated a positive likelihood ratio of 3.76 (95% CI = 2.45 to 5.78), but was not useful to identify a lower risk subset (negative likelihood ratio 0.46; 95% CI = 0.34 to 0.64). On the other hand, a Carpenter score of >1 to define “high-risk” yielded optimal predictive accuracy with a positive likelihood ratio of 2.40 (95% CI = 1.95 to 2.8) and a negative likelihood ratio of 0.11 (95% CI = 0.06 to 0.20).

AUTHOR COMMENTS

Confronted with increasing expectations from payers and geriatric patient organizations to improve the quality and outcomes of older adult emergency care while reducing readmissions and ED revisits, these data provide clinicians and investigators the highest-quality evidence on fall risk stratification. Research evidence on this topic is surprisingly sparse and significant quality issues were identified including lack of adherence to STARD criteria and 39% lost to follow-up for the study by Carpenter et al. Funded, larger multicenter ED-based fall-risk studies are needed.6 Nonetheless, until such data are available these prognostic accuracy estimates provide a starting point for health care providers, funders, and guideline developers to use in deriving screening protocols.

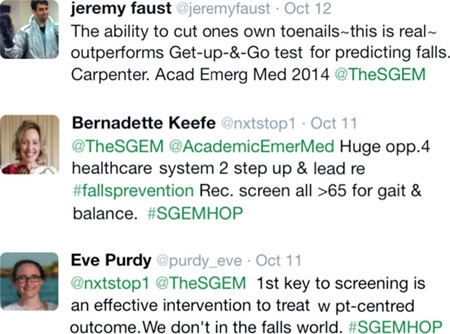

TOP 5 SoMe (SOCIAL MEDIA) COMMENTS

Anand Swaminathan, New York University (comment on The Skeptics Guide to Emergency Medicine [SGEM] blog)

This isn’t something we spend a lot of time discussing but as the population ages, we clearly need to focus on it. In our ED, we often used to admit older patients with falls as “cannot rule out syncope” to get them further assessment by rehabilitation and visiting nursing services. Now, however, changes in admitting policies make this difficult. Many of these patients now go into observation protocols. What likely needs to be added to these protocols are mandatory physical medicine and rehabilitation assessment and assessment for home services in patients over a certain age.

ACEP Geriatric Section (comments on SGEM blog)

I agree that we cannot provide false assurances to family that emergency medicine personnel can either accurately identify older adults at increased risk for falls or be certain that identification of fall risk provides definitive management options for their loved ones. Nonetheless, what is our alternative—to maintain the status quo, which is essentially do no screening and ignore the guidelines (see http://pmid.us/22224145 and http://pmid.us/15982758)

TAKE TO WORK POINTS

Standing-level falls are the number one cause of traumatic mortality in people over age 65 years, and falls also precipitate functional decline and perhaps preventable ED returns. Unfortunately, evidence-based medicine has yet to identify accurate methods to predict which senior citizens will fall in the months following an ED visit. The ability of patients to cut their own toenails and one decision instrument most accurately identified ED patients at lower risk for post-ED falls, but both await validation after a single-center trial. Quantifying fall risk is essential for efficient allocation of scant ED and community resources, but is equally important for fall prevention interventions, which need to be adaptive to the individual patient’s unique fall risk factors. Bottom line: remain cognizant of geriatric fall risk and continue to monitor the research world for pragmatic ED fall risk screening instruments and effective fall prevention protocols.

Footnotes

Associated podcast: http://tinyurl.com/SGEM-GeriatricFalls2014.

The authors have no relevant financial information or potential conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Hogan TM, Losman ED, Carpenter CR, et al. Development of geriatric competencies for emergency medicine residents using an expert consensus process. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:316–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carpenter CR, Bromley M, Caterino JM, et al. Optimal older adult emergency care: introducing multidisciplinary geriatric emergency department guidelines from the American College of Emergency Physicians, American Geriatrics Society, Emergency Nurses Association, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:806–809. doi: 10.1111/acem.12415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carpenter CR. Falls and fall prevention in the elderly. In: Kahn JH, Magauran BG, Olshaker JS, editors. Geriatric Emergency Medicine Principles and Practice. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press; 2014. pp. 343–350. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carpenter CR, Avidan MS, Wildes T, Stark S, Fowler S, Lo AX. Predicting community-dwelling older adult falls following an episode of emergency department care: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:1069–1082. doi: 10.1111/acem.12488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayden SR, Brown MD. Likelihood ratio: A powerful tool for incorporating the results of a diagnostic test into clinical decisionmaking. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33:575–580. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70346-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carpenter CR, Shah MN, Hustey FM, Heard K, Miller DK. High yield research opportunities in geriatric emergency medicine research: prehospital care, delirium, adverse drug events, and falls. J Gerontol Med Sci. 2011;66:775–783. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]