Abstract

Background

Although rare, spinal arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are thought to be more prevalent in the hereditary Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT) population.

Methods

We report a case of a spinal AVM in a 37-year-old female with HHT treated with endovascular embolization. In addition, we report findings from a systematic review of the literature on the clinical characteristics, angioarchitecture, and clinical outcomes of HHT patients with spinal AVMs.

Results

The patient is a 37 year-old female with definite HHT who presented with a one-year history of progressive gait difficulty. The spinal fistula was incidentally detected on chest computed tomography (CT). Spinal angiography demonstrated a large perimedullary arteriovenous fistula was supplied by a posterolateral spinal artery. The fistula was treated with detachable coils. The patient made a complete neurological recovery. Our systematic review yielded 25 additional cases of spinal AVMs in HHT patients. All fistulae were perimedullary (100.0%). Treatments were described in 24 of the 26 lesions. Endovascular-only treatment was performed in 16 cases (66.6%) and surgical-only treatment was performed in five cases (20.8%). Complete or near-complete occlusion rates were 86.7% (13/15) for endovascular treated cases, 100.0% (4/4) for surgery and 66.6% (2/3) for combined treatments. Overall, 80.0% of patients (16/20) reported improvement in function following treatment, 100.0% (5/5) in the surgery group and 84.6% (11/13) reported improvement in the endovascular group.

Conclusions

Spinal fistulae in HHT patients are usually type IV perimedullary fistulae. Both endovascular and surgical treatments appeared to be effective in treating these lesions. However, it is clear that endovascular therapy has become the preferred treatment modality.

Keywords: Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, spinal fistula

Introduction

Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT), also known as Rendu-Osler-Weber syndrome, is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by the presence of multiple mucocutaneous telangiectasia, recurrent spontaneous epistaxis, and arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) in the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, and central nervous system.1,2 Spinal AVMs are rarely encountered among HHT patients with an estimated prevalence of less than 1%3 and the vast majority are found in children. We report a case of a spinal AVM in a 37-year-old female with HHT treated with endovascular embolization as well as a systematic review of the literature on the clinical characteristics, angioarchitecture and clinical outcomes of HHT patients with spinal AVMs.

Case report

History and examination

The patient is a 37-year-old female with a personal and family history of HHT who presented with a one-year history of progressive gait difficulty, left leg spasticity, falls, and urinary urgency. When the patient was eight years old she suffered a subarachnoid hemorrhage and was subsequently diagnosed with two cerebral AVMs which were resected. She had no residual deficits from the AVM rupture and surgeries. The patient also had a history of multiple pulmonary AVMs which were treated with coil embolization.

Physical exam demonstrated spasticity and hyper-reflexia of the left leg. She had distal weakness with a left foot drop. Toes were up-going bilaterally. Sensation to pin prick, vibration sense and joint position were normal throughout. Her gait was markedly abnormal as her left leg was abnormally rotated and circumducted and dragged behind her. She was unable to stand on her heels or toes. There was atrophy of the left leg relative to the right.

Evaluation and treatment

A chest computed tomography (CT), done for evaluation of possible recurrent pulmonary AVMs, revealed a vascular-enhancing lesion in the thoracic spinal canal (Figure 1). Initially, the lesion was followed conservatively elsewhere. However, due to progressive worsening over the course of a year, the patient sought a second opinion at our center. A follow-up chest and thoracic spine computed tomographic angiography (CTA) was performed to further evaluate the lesion and no significant change in the appearance of the spinal arteriovenous fistula was apparent. A spinal angiogram and a cerebral catheter angiography were then pursued as an Magnetic resonance angiography (MRI) could not be performed as the surgical clips from prior cerebral AVM resection were not MRI compatible (Figure 2).

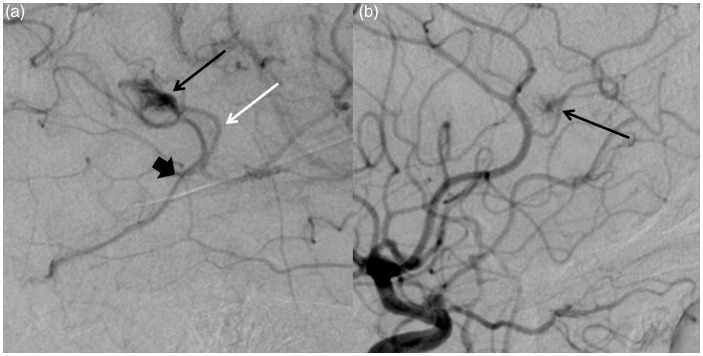

Figure 1.

(a) Right ICA angiogram demonstrates a nidal-type cerebral arteriovenous malformation (AVM) in the high temporal lobe with a feeding artery from an MCA branch without evidence of a feeding aneurysm or substantial dilatation (white arrow). The nidus is small and compact (black arrow). The draining vein demonstrated no ectasia or stenosis (wide black arrow). (b) Left ICA angiogram demonstrates a “micro-AVM” or capillary vascular malformation in the left frontal lobe. The feeding artery was not dilated and there was a small draining vein that filled late.

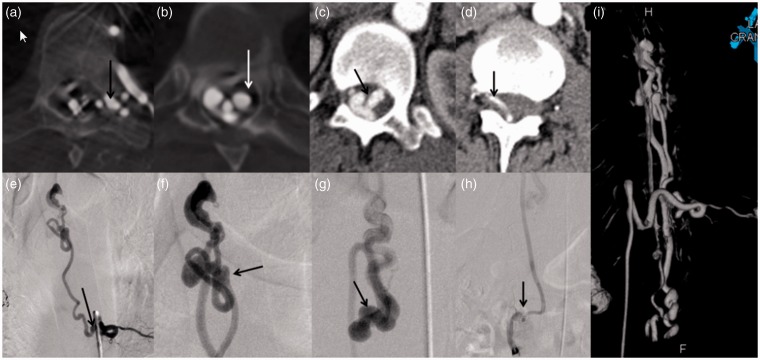

Figure 2.

(a) Flat panel CT image during injection of the left T9 intercostal artery demonstrates a large radiculomeningeal artery entering the left T9 neural foramen (arrow). This is also seen in panel (e) on DSA (black arrow). The site of the fistula was at T6 (white arrow on panel (b) and black arrow on panel (f)). Dilated transmedullary venous anastomoses at the level of T12 are seen on panel (c) (black arrow) and (g) (black arrow). Venous drainage was not only along the perimedullary venous system, but also through the left L2 radicular vein into the IVC ((d) and (h)). The 3D reconstruction of the fistula is demonstrated in panel (i).

The spinal angiogram demonstrated a large perimedullary arteriovenous fistula which was supplied by a posterolateral spinal artery arising from a radiculopial artery at the level of T9 on the left (Figure 3). The anterior spinal artery also arose from the left T9 intercostal artery but was not supplying the fistula. There was a markedly dilated perimedullary vein coursing along the entire surface of the spinal cord. The point of the fistula was located along the anterior surface of the spinal cord at T6 where there was a dilated venous pouch.

Figure 3.

(a) Pre-embolization angiogram again demonstrated the feeding artery/posterolateral spinal artery arising off of T9 with the fistulous connection at the site of the ectatic vein (black arrow). The artery of Adamkiewicz is also fed by the left T9 intercostal artery but is not supplying the fistula (white arrows). (b) The microcatheter tip was placed in the distal aspect of the feeding artery during coil embolization (black arrow). Coil embolization of the fistulous connection and distal feeding artery was performed with complete angiographic occlusion.

Embolization procedure

Due to the patient’s progressive symptoms, the decision was made to proceed with endovascular treatment of the spinal arteriovenous fistula. The left T9 intercostal artery was selectively catheterized with a 5 French Mikaelsson catheter. A microcatheter was then advanced into the artery supplying the fistula. The catheter was advanced superiorly in the spinal canal and when the catheter could no longer be advanced, 12 detachable coils were placed within the venous pouch at the site of the fistula as well as in the distal aspect of the feeding artery. There was complete angiographic resolution of the fistula. The patient was kept on a heparin drip for 24 h and discharged on daily aspirin.

Follow-up

The patient reported complete resolution of her symptoms and was able to regain her left lower extremity strength, and was even able to exercise on an elliptical machine. At last clinical follow-up, four years following the procedure, she reported no back pain, no sensory symptoms, and no loss of motor function. She refused follow-up catheter angiograms.

Systematic review

Materials and methods

Literature search

A reference librarian performed a literature search of OVID, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Web of Science for all clinical studies or case reports of spinal AVMs and fistulae in HHT patients using the key words: “hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia,” “Osler-Weber-Rendu,” “HHT,” “spinal arteriovenous malformation,” “spinal arteriovenous fistula,” “pial arteriovenous fistula,” and “spine”. Databases were searched from 1 January 1970–8 January 2015. Articles were included if they reported on the presence and/or treatment of spinal AVMs in patients with HHT. Case reports and case series published in the English language were included in this study.

Data abstraction and analysis

From each study a single experienced reviewer abstracted the following patient baseline characteristics: patient age, gender, mutation, HHT type, other HHT manifestations, and clinical presentation. The following information was obtained regarding the angiographic characteristics of the fistula: hemorrhage, location, type of fistula, presence of multiple arterial feeders, arterial aneurysms or venous varix, and anterior or posterior spinal artery supply. The following treatment data were obtained: type of treatment, angiographic occlusion, and clinical outcome. These data were entered into a standard data abstraction form. Only descriptive statistics are reported.

Systematic review results

Literature search

The initial literature search yielded 136 articles. Of these, 102 were excluded following reading of the abstract, and 34 full-text articles were obtained. Two were excluded as they were written in the French language and no translator was available. Seventeen articles were excluded as they did not specifically report outcomes or presence of spinal vascular malformations in HHT patients. Twenty-two articles with a total of 25 patients were included in this study. There was overlap of patients reported in two centers, Bicêtre10,11 and University of Toronto.20,21 Thus, this systematic review included patients from 15 centers. Including the above case report. A total of 26 patients with spinal AVMs were included in this review.4–25

Demographics, genetics and other HHT manifestations

Mean patient age was 10.7 ± 17.4 years (range 1 month–72 years). Ten patients (38.5%) were younger than two years and 22 patients (84.6%) were under the age of 18 years. There was a male predominance in this cohort as 18 patients (72.0%) were male and seven patients (28.0%) were female. Although all of the patients had clinically declared HHT, genetic data were available for only six patients. Four patients had mutations in the ACVRL1 gene and two patients had mutations in the ENG gene, thus four patients had HHT2 and two patients had HHT1.

The presence or absence of additional clinical manifestations of HHT were available for 14 patients. Of these, five (34.7%) had cerebral AVMs, seven (50.0%) had epistaxis, three had mucocutaneous lesions (21.4%), and one had pulmonary AVMs (7.1%). These data are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of patient characteristics.

| Study, author and year | Age | Gender | HHT1/2 | Mutation | Presentation | Hemorrhage? | Other HHT manifestations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sivasankar et al., 20144 | 52 | M | NA | NA | Mild sensory loss | N | CAVM, Epi, MCL |

| Kalani et al., 20125 | 5 | F | NA | NA | Paraplegia | N | NA |

| Calhoun et al., 20126 | 2 | M | 1 | ENG (c1A > G) | Quadriplegia and respiratory distress | N | None |

| Calhoun et al., 20126 | 0.1 | F | 2 | ACVRL1 (c998 G > T) | Cardiopulmonary arrest, seizure, SAH | Y | None |

| Poisson et al., 20098 | 6 | M | 1 | ENG | Acute paraplegia | Y | Epi |

| Poisson et al., 20098 | 0.7 | M | 2 | ALK-1 | Subacute paraplegia | N | None |

| Ricolfi et al., 199722 | 5 | M | NA | NA | SAH with paraplegia | Y | None |

| Mandzia and Mei-Zahav, 19999, 200620 | 8 | M | 2 | ACVRL1 (c1232G > A) | Paraplegia, urinary retention | N | Epi |

| Mandzia and Mei-Zahav, 19999, 200620 | 9 | M | 2 | ACVRL1 (c1232G > A) | LOC, Seizures | N | Epi |

| Stephan et al., 200512 | 3 | M | NA | NA | Incidental on abdominal CT | N | CAVM |

| Bicêtre experience, 200510–200611 | 1 | M | NA | NA | Paraparesis and sphincter dysfunction | Y | NA |

| Bicêtre experience, 200510–200611 | 6 | NA | NA | NA | Quadripalegia | Y | NA |

| Bicêtre experience, 200510–200611 | 0.25 | M | NA | NA | Opisthotonus | N | NA |

| Bicêtre experience, 2005–200611 | 1 | M | NA | NA | Somnolence and vomiting | Y | NA |

| Bicêtre experience, 200510–200611 | 0.1 | M | NA | NA | Paraparesis | N | NA |

| Bicêtre experience, 200510–200611 | 0.7 | M | NA | NA | Quadriparesis, resp distress | Y | NA |

| Bicêtre experience, 200510–200611 | 0.5 | M | NA | NA | Hypotonia | Y | NA |

| Ling et al., 200514 | 14 | M | NA | NA | Paraplegia and sphincter dysfunction | Y | Epi |

| Mont'Alverne, 200315 | 18 | M | NA | NA | Paraparesis | N | CAVM |

| Halbach et al., 199324 | 7 | F | NA | NA | SAH | Y | NA |

| Halbach et al., 199324 | 7 | F | NA | NA | Acute paraplegia | N | NA |

| Kaplan et al., 197631 | 1.3 | F | NA | NA | Flacid paraplegia | N | MCL |

| Meng, 20107 | 5 | M | NA | NA | Gait weakness | N | NA |

| Meisel, 199623 | 15 | M | NA | NA | Paraparesis and SAH | Y | NA |

| Roman et al., 197825 | 72 | F | NA | NA | SAH, nausea, headache, fever | Y | CAVM, Epi, MCL |

| Current study | 39 | F | NA | NA | Left lower extremity spasticity | N | CAVM, Epi, PAVM |

F: female; HHT: hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia; M: male; N: no; NA: not available; Y: yes; PAVM: N-butyl cyanoacrylate; MCL: mucocutaneous lesions; Epi: epistaxis; CAVM: cerebral arteriovenous malformation; AVF: arteriovenous fistula; PSA: posterior spinal artery; ASA: anterior spinal artery; LOC: loss of consciousness; SAH: subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Clinical presentation and angiographic characteristics

Of the 26 spinal AVMs, 12 (46.2%) had intramedullary or subarachnoid hemorrhage on presentation. Paraplegia/paresis or quadriplegia/paresis was the presenting symptom in 15 cases (57.7%), respiratory distress occurred in two patients (7.7%), seizure occurred in two patients (7.7%), and symptoms of headache secondary to Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH) occurred in five patients (19.2%).

The most common location for the fistula was in the thoracic spine (17 cases, 68.0%). The cervical spine was the second most common location (five cases, 20.0%). All fistulae were perimedullary (100.0%). One patient later developed a dural arteriovenous fistula. No other epidural or dural arteriovenous fistulae were reported. Venous varices were nearly a universal feature of these lesions as 23 of 24 cases had venous varices (95.8%), of which nine were reported as “giant.” Multiple arterial feeders were described in 13 cases. In 11 cases (57.9%), supply from the anterior spinal artery was described, and in 16 cases (84.2%) supply from the posterior spinal artery was described. Compressive myelopathy as a result of giant venous varices was described in four cases.

Treatment

Treatments were described in 24 of the 26 lesions. Endovascular-only treatment was performed in 16 cases (66.6%), surgical-only treatment was performed in five cases (20.8%), and combined treatment was performed in three cases (12.5%). Among patients receiving endovascular treatment, complete or near complete occlusion was reported in nearly all cases (13/15, 86.7%). Complete or near complete occlusion rates were 100.0% (4/4) for surgery and 66.6% (2/3) for combined treatments. Overall, 80.0% of patients (16/20) reported improvement in function following treatment (100.0% (5/5) in the surgery group and 84.6% (11/13) reported improvement in the endovascular group). These data are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Angiographic characteristics and treatment results.

| Study, author and year | Location of fistula | Type of fistula | Angioarchiecture | ASA supply | PSA supply | Compressive symptoms | Treatment | Angiographic occlusion | Clinical outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sivasankar et al., 20144 | C | Perimedullary | Venous varix, multiple arterial feeders | N | Y | N | NA | NA | NA |

| Kalani et al., 20125 | L | Perimedullary/conus medullaris | Venous varix, multiple arterial feeders | NA | NA | Y | S | Complete | + |

| Calhoun et al., 20126 | C, T/L | Perimedullary | Giant venous varix | NA | NA | Y | S | NA | + |

| Calhoun et al., 20126 | L | Perimedullary | Giant venous varix, 2 small pseudoaneurysms | NA | NA | N | ES | Complete | 0 |

| Poisson et al., 20098 | T | Perimedullary | Venous varix, single arterial feeder | Y | N | N | E | NA | + |

| Poisson et al., 20098 | T | Perimedullary | Venous varix, multiple arterial feeders | N | Y | N | E | Complete | + |

| Ricolfi et al., 199722 | T | Perimedullary | Giant venous varix, multiple arterial feeders | Y | Y | Y | E | Complete | 0 |

| Mandzia and Mei-Zahav, 19999, 200620 | T | Perimedullary | Venous varix, multiple arterial feeders | N | Y | N | S | Complete | + |

| Mandzia and Mei-Zahav, 19999, 200620 | T | Perimedullary | Giant venous varix | N | Y | N | E | Complete | + |

| Stephan et al., 200512 | T | Perimedullary | Giant venous varix, multiple arterial feeders | N | Y | Y | E | Complete | NA |

| Bicêtre experience, 200510–200611 | Conus | Perimedullary | Venous varices and stenosis | Y | Y | NA | E | Complete | + |

| Bicêtre experience, 200510–200611 | NA | Perimedullary | Venous varices and stenosis | Y | Y | NA | E | Complete/near complete | NA |

| Bicêtre experience, 200510–200611 | T | Perimedullary | Venous varices and stenosis | Y | Y | NA | E | Complete | + |

| Bicêtre experience, 200510–200611 | C | Perimedullary | Venous varices and stenosis | Y | Y | NA | E | Complete | + |

| Bicêtre experience, 200510–200611 | T/L | Perimedullary | Venous varices and stenosis | Y | Y | NA | E | Complete | + |

| Bicêtre experience, 200510–200611 | C | Perimedullary | Venous varices and stenosis | Y | Y | NA | E | Near complete | + |

| Bicêtre experience, 200510–200611 | T | Perimedullary | Venous varices and stenosis | Y | Y | NA | E | Complete | + |

| Ling et al., 200514 | T | Perimedullary, later developed a dural AVF | Multiple arterial feeders | N | Y | N | S | Complete | + |

| Mont'Alverne, 200315 | TL | Perimedullary | Giant venous varix, multiple arterial feeders | Y | Y | N | E | Complete | + |

| Halbach et al., 199324 | L | Perimedullary | Giant venous varix, multiple arterial feeders | NA | NA | NA | E | Complete | NA |

| Halbach et al., 199324 | C | Perimedullary | Giant venous varix, multiple arterial feeders | NA | NA | NA | ES | Near complete | NA |

| Kaplan et al., 197631 | T/L | Perimedullary | Giant venous varix, multiple arterial feeders | NA | NA | NA | S | Near complete | + |

| Meng, 20107 | T | Perimedullary | NA | NA | NA | NA | E | Near complete | 0 |

| Meisel, 199623 | T | Perimedullary | Multiple arterial feeders, large venous varix, venous stenoses | Y | N | NA | SE | Multiple recurrences | – |

| Roman et al., 197825 | T | NA | NA | N | N | NA | None | NA | NA |

| Current study | T | Perimedullary | Multiple venous varices | N | Y | N | E | Complete | + |

C: cervical; E: endovascular; L: lumbar; N: no; NA: not available; S: surgery; T: thoracic; Y: yes.

Improvement is indicated by + and worsening by – sign.

Discussion

Our case report and review of the literature demonstrates a number of interesting findings regarding the clinical and angiographic characteristics as well as treatment outcomes of spinal arteriovenous fistulae in HHT patients. In general, HHT patients presenting with these lesions are young with approximately 85% of patients being younger than 18 and about 40% of patients being younger than two years old. Interestingly, there was a striking male predilection with 72% of patients being male. These lesions generally presented with acute to subacute onset of severe neurological deficits such as paraplegia or quadriplegia and about 50% of lesions presented with intramedullary or subarachnoid hemorrhage. All patients had perimedullary fistulae and in general the angioarchitecture of these lesions was complex. Lastly, both endovascular and surgical treatments appeared to be effective in treating these lesions. However, it is clear that endovascular therapy has become the preferred treatment modality. These findings are important as they provide a comprehensive overview of the clinical, angiographic, and treatment characteristics of spinal arteriovenous fistulae in HHT patients.

The exact prevalence of spinal vascular malformations in HHT patients is unknown, however it is generally accepted to be substantially higher than in the general population. In our literature review, we were able to compile just 26 cases of spinal arteriovenous fistulae in HHT patients, suggesting that these lesions are rare, even in this AVM-predisposed population. However, in their review of perimedullary arteriovenous fistulae, Gross and Du found that over 10% of cases in the literature were reported in associated with HHT.26 Thus, it is apparent that there is likely a strong association between HHT and the formation of these perimedullary fistulae. Despite the fact that these lesions are more common in the HHT population, current recommendations do not support routine screening for spinal vascular malformations. Thus most of these lesions are detected only when symptomatic.3 In our study, only one case was detected incidentally, while the rest presented with moderate to severe symptoms.

Little is known regarding the pathophysiology of these lesions. In general, AVMs in HHT patients are considered not to be congenital; rather they are presumed to develop early in infancy when arteriovenous maturation occurs and vessels are continuously being developed.15 The cerebral venous system is immature at birth and matures, through pro-angiogenic stimuli throughout the early life of the child.27 It is conceivable that HHT-associated mutations result in a hyper-response to these pro-angiogenic stimuli; thus the higher prevalence of cerebral AVMs in the HHT population.28,29 However, no studies to date have demonstrated the postnatal maturation of the spinal venous system. Other proposed mechanisms for the formation of spinal and cerebral AVMs in the HHT population include inflammation/infection, endoluminal shear stress, and hypoxemia.

The natural history of these lesions has not been systematically studied due to the rarity of the lesions and the need for urgent treatment when they present. In our patient, the fistula was followed up for at least one year and she developed progressive worsening of symptoms over time. No appreciable change was seen in the appearance of the fistula between imaging examinations. In Gross and Du's series of type IV pial fistulae, the annual hemorrhage rate was 2.5% overall with annual hemorrhage rates of 5.6% for lesions that previously bled and 0.4% for lesions that were unruptured.26 Rates of symptom progression aside from rupture have not been well documented.

In general, the spinal AVFs seen in HHT patients were high-flow lesions in the perimedullary/subpial space with multiple arterial feeders. As seen in the case report, ectasia of the vein generally marked the transition point between the artery and vein. The clinical and angiographic characteristics of these lesions in HHT patients are most consistent with those of the Anson-Spetzler type IVc fistulae which are characterized as giant, multi-feeder, high flow shunts with dilated tortuous veins. In Gross and Du's review, HHT patients comprised nearly 25% of type IVc lesions.26 Acute motor deficits were the most common presenting symptoms and up to one-half of cases presented with subarachnoid hemorrhage or hematomyelia, similar to our series.

Endovascular embolization is the preferred treatment modality for spinal vascular malformations seen in HHT as the majority of type IVc fistulae in general are primarily treated endovascularly (80%).26 Techniques described in the literature include liquid adhesives (n-BCA), coil embolization, and balloon embolization.30 Flow-directed microcatheters are preferred as they allow for distal positioning at the site of the fistula. Embolization at the site of the fistula is essential to decrease the risk of development of future collaterals. Given the size of the venous varix at the point of the fistula, these cases often require deployment of multiple coils or high concentrations of glue in order to achieve complete occlusion. Special care must be taken to avoid reflux of the embolic agent as this could result in devastating consequences from spinal cord infarction as these lesions are supplied by anterior and/or posterior spinal arteries. Many authors have advocated the use of spinal cord monitoring, either electrophysiologic or chemical (amobarbital) in order to prevent the devastating complication of a spinal cord infarction.30 Following embolization, some authors also advocate the use of aggressive anticoagulation with a heparin drip, as in this case, in order to prevent thrombosis of the medullary arteries, or mass effect due to acute thrombosis of the large/giant venous varices.30 In general, the rate of angiographic or clinical improvement is over 70% and complications are rare.26

Conclusions

Our case report and systematic literature review of 26 HHT patients with spinal arteriovenous fistulae demonstrated a number of interesting findings. These patients generally presented with acute deficits and nearly 50% of patients had rupture of the fistula. All patients had perimedullary fistulae and in general the angioarchitecture of these lesions was complex. Both endovascular and surgical treatments appeared to be effective in treating these lesions, however it is clear that endovascular therapy has become the preferred treatment modality.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Shovlin CL, Guttmacher AE, Buscarini E, et al. Diagnostic criteria for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber syndrome). Am J Med Genet 2000; 91: 66–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDonald J, Wooderchak-Donahue W, VanSant Webb C, et al. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: Genetics and molecular diagnostics in a new era. Front Genet 2015; 6: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faughnan ME, Palda VA, Garcia-Tsao G, et al. International guidelines for the diagnosis and management of hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. J Med Genet 2011; 48: 73–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sivasankar R, Saraf R, Pawal S, et al. Cerebral and spinal vascular involvement in hereditary hemorrhagic telengiectasia: Report of two cases. J Vasc Interv Neurol 2014; 7: 1–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalani MY, Ahmed AS, Martirosyan NL, et al. Surgical and endovascular treatment of pediatric spinal arteriovenous malformations. World Neurosurg 2012; 78: 348–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calhoun AR, Bollo RJ, Garber ST, et al. Spinal arteriovenous fistulas in children with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2012; 9: 654–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meng X, Zhang H, Wang Y, et al. Perimedullary arteriovenous fistulas in pediatric patients: Clinical, angiographical, and therapeutic experiences in a series of 19 cases. Childs Nerv Syst 2010; 26: 889–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poisson A, Vasdev A, Brunelle F, et al. Acute paraplegia due to spinal arteriovenous fistula in two patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Eur J Pediatr 2009; 168: 135–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mei-Zahav M, Letarte M, Faughnan ME, et al. Symptomatic children with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: A pediatric center experience. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2006; 160: 596–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krings T, Ozanne A, Chng SM, et al. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: Neurovascular phenotypes and endovascular treatment. Clin Neuroradiol 2006; 16: 76–90. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cullen S, Alvarez H, Rodesch G, et al. Spinal arteriovenous shunts presenting before 2 years of age: Analysis of 13 cases. Childs Nerv Syst 2006; 22: 1103–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stephan MJ, Nesbit GM, Behrens ML, et al. Endovascular treatment of spinal arteriovenous fistula in a young child with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Case report. J Neurosurg 2005; 103: 462–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodesch G, Hurth M, Alvarez H, et al. Spinal cord intradural arteriovenous fistulae: Anatomic, clinical, and therapeutic considerations in a series of 32 consecutive patients seen between 1981 and 2000 with emphasis on endovascular therapy. Neurosurgery 2005; 57: 973–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ling JCM, Agid R, Nakano S, et al. Metachronous multiplicity of spinal cord arteriovenous fistula and spinal dural AVF in a patient with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. Interv Neuroradiol 2005; 11: 79–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krings T, Ozanne A, Chng SM, et al. Neurovascular phenotypes in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia patients according to age. Review of 50 consecutive patients aged 1 day–60 years. Neuroradiology 2005; 47: 711–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krings T, Chng SM, Ozanne A, et al. Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia in children. Endovascular treatment of neurovascular malformations – Results in 31 patients. Interv Neuroradiol 2005; 11: 13–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krings T, Chng SM, Ozanne A, et al. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia in children: Endovascular treatment of neurovascular malformations. Neuroradiology 2005; 47: 946–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodesch G, Hurth M, Alvarez H, et al. Angio-architecture of spinal cord arteriovenous shunts at presentation. Clinical correlations in adults and children: The Bicêtre experience on 155 consecutive patients seen between 1981–1999. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2004; 146: 217–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mont'Alverne F, Musacchio M, Tolentino V, et al. Giant spinal perimedullary fistula in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia: Diagnosis, endovascular treatment and review of the literature. Neuroradiology 2003; 45: 830–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mandzia JL, ter Brugge KG, Faughnan ME, et al. Spinal cord arteriovenous malformations in two patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Childs Nerv Syst 1999; 15: 80–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emery DJ, Willinsky RA, Burrows PE, et al. Paediatric spinal arteriovenous malformations: Angioarchitecture and endovascular treatment. Interv Neuroradiol 1998; 4: 127–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ricolfi F, Gobin PY, Aymard A, et al. Giant perimedullary arteriovenous fistulas of the spine: Clinical and radiologic features and endovascular treatment. AJNR 1997; 18: 677–687. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meisel HJ, Lasjaunias P, Brock M. Multiple arteriovenous malformations of the spinal cord in an adolescent: Case report. Neuroradiology 1996; 38: 490–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halbach VV, Higashida RT, Dowd CF, et al. Treatment of giant intradural (perimedullary) arteriovenous fistulas. Neurosurgery 1993; 33: 972–979; discussion: 979–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roman G, Fisher M, Perl DP, et al. Neurological manifestations of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber disease): Report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Ann Neurol 1978; 4: 130–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gross BA, Du R. Spinal pial (type IV) arteriovenous fistulae: A systematic pooled analysis of demographics, hemorrhage risk, and treatment results. Neurosurgery 2013; 73: 141–151; discussion: 151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lasjaunias P, Berenstein A and ter Brugge KG. Spinal and spinal cord arteries and veins. Clinical vascular anatomy and variations. Heidelberg: Springer, 2001, pp. 73–164.

- 28.Han C, Choe SW, Kim YH, et al. VEGF neutralization can prevent and normalize arteriovenous malformations in an animal model for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia 2. Angiogenesis 2014; 17: 823–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mahmoud M, Allinson KR, Zhai Z, et al. Pathogenesis of arteriovenous malformations in the absence of endoglin. Circulation Research 2010; 106: 1425–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berenstein A and Lasjaunias P. Endovascular treatment of spine and spinal cord lesions. Berlin: Springer, 1992, pp. 18–85.

- 31.Kaplan P, Hollenberg RD and Fraser FC. A spinal arteriovenous malformation with hereditary cutaneous hemangiomas. Am J Dis Child 1976; 130: 1329–1331. [DOI] [PubMed]