Abstract

For a series of five model complexes composed of a singlet SnX2 molecule (X = H, F, Cl, Br, I) and a benzene molecule, the first-principles calculations of their energetics and the analysis of their electron density topology have been performed. The CCSD(T)/CBS interaction energy between SnX2 and C6H6 fall into the range between −10.0 and −11.2 kcal/mol, which indicates that the complexes are rather weakly bound. The relevant role of electrostatic and dispersion contributions to the interaction energy between SnX2 and C6H6 is highlighted in the results obtained from the symmetry-adapted perturbation theory (SAPT). The electron density topological analysis has been carried out using the quantum theory of atoms in molecules (QTAIM) and the noncovalent interactions (NCI) visualization index. Both QTAIM and NCI prove the closed-shell, noncovalent and attractive character of the interaction. A very small charge transfer from C6H6 to SnX2 has been detected. The formation of the five complexes is accompanied by the electron density deformations that are spatially restricted mostly to the region around the Sn atom and its adjacent C atom. The results presented in this work shed some light on the nature of the interactions associated with crystalline structural motifs involving low-valent tin complexed with neutral aryl rings.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00894-016-3053-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Tin complexes, Divalent tin, Benzene, Intermolecular interaction

Introduction

Interaction between metals and π-electron systems of neutral aryl rings is an interesting bonding motif for supramolecular self-assembly [1]. For instance, various transition metals interacting with benzene rings form both simple π-complexes in the gas phase [2–4] and larger supramolecular structures with this bonding motif [5–7]. However, the knowledge on the complexes of the heavier metals of groups 13–16 with neutral arenes is rather limited [8]. Tin is a good example in this context. The results of crystallographic studies [9] indicate that intermolecular Sn · · · π interactions often involve low-valent tin atoms, and therefore the complexation of stannylenes [10] by neutral aryl rings has attracted much interest in recent years [11–14].

In this work, a series of five systems composed of a singlet tin(II) dihydride or dihalide SnX2 (X = H, F, Cl, Br, I) molecule and a benzene molecule is considered. From a computational viewpoint, such systems may be regarded as model systems that approximate real systems in which the complexation of stannylenes by the π-electron cloud of neutral aryl rings occurs [9]. We focus mostly on the energetic and electron density topological description of the interaction between SnX2 and C6H6 in the resulting complexes: SnH2 · · · C6H6 (1), SnF2 · · · C6H6 (2), SnCl2 · · · C6H6 (3), SnBr2 · · · C6H6 (4), and SnI2 · · · C6H6 (5). Such quantum-chemical theories as the symmetry-adapted perturbation theory [15, 16] in both its traditional formulation (HF-SAPT) and its variant based on the density functional theory (DFT-SAPT), the quantum theory of atoms in molecules (QTAIM) [17], and the noncovalent interactions (NCI) visualization index [18] are used to provide an in-depth insight into this interaction. The present investigation is an extension of our previous work [19] in which only limited characteristics of 1–5 were obtained because some basic geometrical and energetic parameters were sufficient for our benchmark assessment of the accuracy of the Møller–Plesset second-order perturbation theory (MP2) and the density functional theory (DFT). There is also another theoretical study of the interaction of SnX2 with C6H6 [20]. In that study, the properties of various SnX2 molecules were characterized by conceptual DFT reactivity indices and the complexation of SnX2 with a series of potential aromatic π-donors was examined. In particular, it was deduced from the results of natural bond orbital (NBO) calculations that the most important orbital interaction for this complexation was the overlap of the formally empty p-orbital on the Sn atom and the π-orbitals of the C6H6 molecule. Here, we employ not only a wide variety of first-principles methods for inspecting the energetics of the interaction between SnX2 and C6H6 but additionally we explore the interaction in the complexes 1–5 from the perspective of their electron density topology.

Computational details

The geometries of 1–5 are taken from our previous study [19] in which they were optimized at the ωB97X/aug-cc-pVTZ(-PP) level of theory [21–24]. These geometries are characterized by the absence of imaginary vibrational frequencies and they correspond to global minima on the potential energy surfaces of 1–5 (see also section S1 in Electronic Supplementary Material). Throughout this entire work, the aug-cc-pVTZ basis set [22] is ascribed to the atoms of H, C, F, Cl, and Br, whereas the aug-cc-pVTZ-PP basis set [23] is used for Sn and I. Their 28 core electrons are described by the corresponding energy-consistent Stuttgart/Cologne MDF pseudopotentials [24]. These pseudopotentials allow us to indirectly account for relativistic effects in Sn and I.

The formation of each complex is characterized by its complexation energy Ecomplex that is defined as

| 1 |

where Edef is the so-called deformation energy needed to change the geometries of SnX2 and C6H6 from those exhibited by isolated molecules to those observed in the complex, Eint is the interaction energy between SnX2 and C6H6 in the complex and ΔZPVE denotes the difference in the unscaled zero-point vibrational energies of the isolated SnX2 and C6H6 molecules and the SnX2 · · · C6H6 complex. Eint can be computed using either supermolecular or perturbative approach. According to the former, subtracting the total energies of SnX2 and C6H6 in their geometries observed in the complex from the total energy of the SnX2 · · · C6H6 complex constitutes Eint. In this work, both DFT methods (such as SVWN [25, 26], BLYP [27, 28], B3LYP [28, 29], M06-2X [30] and ωB97X [21]), and wave function theory (WFT) methods (such as HF [31, 32], MP2 [33], SCS-MP2 [34], CCSD [35], and CCSD(T) [35]) are used to obtain Eint within the framework of the supermolecular approach. The Eint energies yielded by the HF and DFT methods are corrected for the basis set superposition error using the full counterpoise method of Boys and Bernardi [36]. The “half-half” counterpoise correction [37] is included in the Eint energies calculated using MP2, SCS-MP2, CCSD, and CCSD(T). The Eint energies at the CCSD(T) level of theory are additionally extrapolated to the complete basis set (CBS) limit via a composite scheme (for details, see section S2). The MP2, SCS-MP2, CCSD, and CCSD(T) methods make use of the frozen core approximation in the treatment of core electrons. All the calculations described in this paragraph have been done with Gaussian D.01 [38] and TURBOMOLE 6.6 [39] (for the DFT and WFT methods, respectively).

The SAPT method is used to determine the Eint energy between SnX2 and C6H6 in a perturbative manner. Within the framework of this method, Eint is expressed as a sum of several energy terms that can be grouped into four principal components with clear physical meanings. The components covering exchange (Eexch), electrostatics (Eelst), induction (Eind), and dispersion (Edisp) are assumed to include the following energy terms occurring in the SAPT expansion of Eint:

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

The HF-SAPT [15, 16] and DFT-SAPT [40, 41] variants are employed. The gradient-regulated asymptotic correction of Grüning et al. [42] with the PBE0 functional [43] is introduced into the DFT-SAPT calculations of Eint in order to improve the asymptotic behavior of the DFT-SAPT variant. All the SAPT calculations have been performed using the MOLPRO 2012.1 program [44, 45].

The QTAIM analysis of the topology of the electron density in 1–5 and the calculations of QTAIM properties have been done with the AIMAll 14.11.23 program [46]. The Multiwfn 3.3 program [47] has been used to perform the NCI analysis and to obtain a signature of electron pair distribution in terms of the electron localization function (ELF) [48]. The results are visualized using Jmol 14.2 [49], AIMStudio 14.11.23 [46], and VMD 1.9 [50].

Results and discussion

Structure and stability

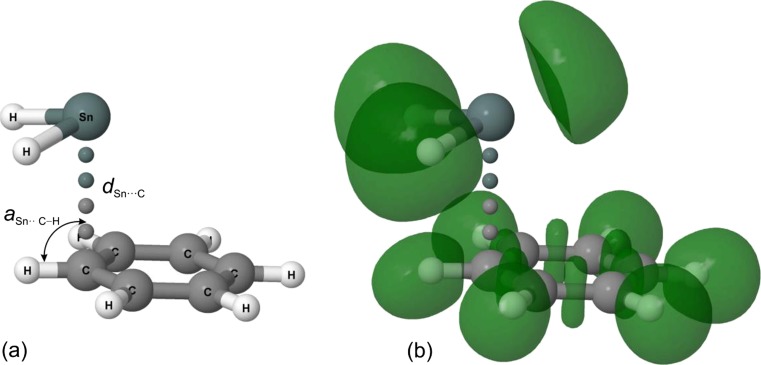

Let us start by presenting the optimized geometries of 1–5. All these complexes exhibit a marked structural similarity in which the SnX2 molecule is arranged above the C6H6 ring (see Fig. 1a). The molecular plane of SnX2 is approximately parallel to the plane of the C6H6 ring. All five complexes are of Cs symmetry. The Sn atom sits nearly on one of the C atoms, and the X atoms are directed outward the C6H6 ring. The distance between Sn and the C atom beneath (dSn···C) falls in a narrow range between 2.919 and 3.076 Å (see Table S6 in Electronic Supplementary Material). This is much smaller than the sum of the Sn- and C-atom van der Waals radii (2.42 Å for Sn and 1.77 Å for C [51]). The values of the aSn···C–H angle do not differ significantly from 90°, and therefore, they indicate the η1 type of complexation for 1–5.

Fig. 1.

Optimized geometry of 1 with two characteristic geometrical parameters marked (a) or ELF isosurfaces shown (b). These isosurfaces are plotted with a contour value of 0.85

The aforementioned, almost parallel orientation of the SnX2 and C6H6 molecular planes means that the formally empty p-orbital of the Sn atom is nearly perpendicular to the plane of the C6H6 ring. In such an orientation, the π-cloud overlaps the empty p-orbital effectively [20]. The lone electron pair of the Sn atom is positioned opposite the X atoms. Its localization is confirmed by the corresponding ELF isosurface depicted in Fig. 1b.

The comparison of the isolated SnX2 and C6H6 molecules with the corresponding molecular fragments of 1–5 reveals that SnX2 and C6H6 do not suffer any significant structural variations upon complexation (see Table S6). A minor effect of complexation on the geometries of SnF2 and C6H6 molecular fragments constituting a 1:1 complex was confirmed experimentally, using matrix IR spectroscopy [52]. The vibrational frequencies measured for this complex were close to those of SnF2 and benzene substrates, and on this basis, only a slight distortion of SnF2 and C6H6 geometries was deduced. The complexation of Sn(II) by a six-membered aromatic ring was also detected in several crystal structures [11–14]. The structures often revealed the η6 type of Sn(II) complexation, with the distances between Sn(II) and the centroid of the interacting aromatic ring within the range from 3.2 to 4 Å [11, 12]. The lower end of this range is slightly larger than the dSn···C values found for 1–5. Such a shortening of the distance between Sn(II) and the molecular plane of aromatic ring is a consequence of the η1 type of complexation in 1–5.

Energetic effects associated with the complexation of SnX2 with C6H6 are summarized in Table 1. As evidenced by the values of Ecomplex, the formation of 1–5 from the isolated SnX2 and C6H6 molecules is energetically favorable (that is, Ecomplex < 0), although the resulting stabilization of the complexes does not exceed several kcal/mol. The complexation of SnH2 turns out to be slightly less energetically favorable than the complexation of tin(II) dihalides. The values of Edef are small, which is a consequence of the minor structural reorganization of SnX2 and C6H6 upon complexation. For all five complexes, the interaction energy Eint contributes most to Ecomplex. The values of Eint fall in a narrow range between −9.1 and −9.7 kcal/mol, which obviously suggests that the interaction between SnX2 and C6H6 in 1–5 is in fact quite similar. The difference in the energetics of the complexes becomes more significant with the ΔZPVE component included.

Table 1.

Complexation energies and their components calculated using the ωB97X method

| Energy | Complex | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| E def | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| E int | −9.3 | −9.7 | −9.7 | −9.5 | −9.1 |

| ΔZPVE | 1.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| E complex | −7.6 | −8.8 | −8.8 | −8.5 | −8.2 |

All values in kcal/mol

The Eint values shown in Table 1 indicate that the interaction between SnX2 and C6H6 can be classified into the category of weak intermolecular interactions. The interaction investigated here turns out to be much weaker than those involving benzene and alkali or alkaline-earth metal cations [53, 54] but stronger than the interactions in SF2 · · · C6H6 [55] and SeY2 · · · C6H6 (Y = H, F, Cl) [56].

The interaction energies of 1–5 have also been computed at various DFT and WFT levels, all using the geometries optimized by ωB97X/aug-cc-pVTZ(-PP). The calculated values of Eint are reported in Table 2 (the Eint values that are uncorrected by the counterpoise method can be found in Table S7). We now test the reliability of the Eint energies obtained from less computationally expensive levels of theory against the CCSD(T)/CBS results.

Table 2.

Interaction energies calculated using various methods

| Method | Complex | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| HF | −2.1 | −4.5 | −2.9 | −2.6 | −2.1 |

| SVWN | −14.5 | −13.3 | −13.1 | −12.8 | −12.2 |

| BLYP | −3.3 | −1.9 | −0.9 | −0.4 | 0.3 |

| BLYP-D3(BJ) | −11.4 | −10.8 | −11.5 | −11.6 | −11.5 |

| B3LYP | −4.6 | −4.3 | −3.2 | −2.9 | −2.2 |

| B3LYP-D3(BJ) | −11.3 | −11.7 | −12.2 | −12.2 | −12.0 |

| M06-2X | −10.4 | −11.7 | −11.1 | −10.9 | −10.8 |

| ωB97X | −9.3 | −9.7 | −9.7 | −9.5 | −9.1 |

| HF-SAPT | −11.6 | −13.6 | −13.7 | −13.8 | −13.6 |

| DFT-SAPT | −8.8 | −10.0 | −10.4 | −10.5 | −10.3 |

| MP2 | −13.0 | −13.1 | −14.5 | −14.6 | −15.5 |

| SCS-MP2 | −10.5 | −11.0 | −11.9 | −11.9 | −12.5 |

| CCSD | −9.2 | −10.6 | −10.4 | −10.2 | −10.7 |

| CCSD(T) | −10.7 | −11.6 | −11.8 | −11.7 | −12.1 |

| CCSD(T)/CBS | −10.0 | −10.9 | −11.2 | −11.1 | −11.1 |

All values in kcal/mol

The HF method predicts that the interaction between SnX2 and C6H6 leads to the stabilization of 1–5 but the resulting Eint values are very small. Thus, the omission of electron correlation energy results in a major underestimation of the strength of the interaction between SnX2 and C6H6.

The DFT methods present diverse performance, depending on the generation of a given DFT method. The SVWN functional leads to a typical overbinding [57]. In contrast to SVWN, the BLYP and B3LYP functionals predict that the complexes 1–5 are bound too weakly or even unbound (BLYP produces Eint > 0 for 5). The Eint values obtained from B3LYP differ slightly from the corresponding B3LYP values reported in Ref. [20]. These differences originate from a greater number of core electrons described by the pseudopotential of Sn atom during the calculations carried out in Ref. [20]. A common method that can improve the performance of BLYP and B3LYP in predicting the interaction energy of noncovalent complexes is to include an empirical dispersion correction. Here, Grimme’s D3 term with Becke-Johnson damping (D3(BJ)) [58] is employed for BLYP and B3LYP. The application of the D3(BJ) term allows these two functionals to overcome the underestimation of Eint for 1–5. However, both BLYP-D3(BJ) and B3LYP-D3(BJ) yield a minor overbinding in 1–5, which suggests that the D3(BJ) term generally tends to overestimate slightly the role of long-range electron correlation in these complexes. This extends findings reported in a prior study [59]. It was shown therein that B3LYP combined with Grimme’s dispersion correction yielded overbinding for hydrogen-bonded and ionic complexes. A slight overestimation of hydrogen-bond energy in DNA base pairs was also detected for the combination of BLYP with Grimme’s dispersion correction [60, 61]. More recent DFT generations, represented in Table 2 by M06-2X and ωB97X, produce the Eint energies that mirror the CCSD(T)/CBS results fairly closely. It is known that the ωB97X functional has proved to be highly successful at providing accurate bond energies for compounds containing transition metals [62], as well as interaction energies for complexes of Sn(II) [19] and Sn(IV) [63, 64]. The good performance of M06-2X in predicting the Eint energies of 1–5 seems to confirm the important role of medium-range electron correlation for these complexes [30, 65].

As for the SAPT method, its HF-SAPT variant overestimates the strength of the interaction between SnX2 and C6H6, while the DFT-SAPT variant demonstrates the opposite tendency. However, the former produces the Eint energies with worse accuracy relative to the CCSD(T)/CBS results than the latter does. It is so because the HF-SAPT variant applied here makes use of the simplest SAPT formulation, usually called HF-SAPT0 [66], that neglects the effects of intramonomer correlation. The intramonomer correlation effects are accounted for within the framework of the DFT-SAPT variant. It has been recently reported that DFT-SAPT generally underbinds H-bonded complexes [67] and it also proves to be the case with the interaction between SnX2 and C6H6. The maximum DFT-SAPT underestimation of the strength of the interaction in 1–5 amounts to 1.2 kcal/mol — this is observed for 1.

The performance of the advanced WFT methods also demonstrates some characteristic features. The MP2 method systematically overestimates the strength of the interaction between SnX2 and C6H6 due to the omission of the repulsive intramolecular correlation correction within this method [68, 69]. The inclusion of Grimme’s spin-component scaling (SCS) scheme [34] in the MP2 correlation energy reduces the overbinding of 1–5 but the Eint value of 5 is still overestimated by 1.4 kcal/mol. The overestimation occurring in SCS-MP2 results from the application of the “half-half” correction of the basis-set superposition error. However, this correction leads to better agreement with the CCSD(T)/CBS interaction energies than the use of either uncorrected or full counterpoise-corrected values (see Table S8). Similarly to SCS-MP2, the CCSD(T) method also shows an overbinding tendency in Eint. Again, it is due to the application of the “half-half” correction. The Eint values yielded by CCSD are too small, which points at the importance of triple excitations in the correlation energy of 1–5.

The CCSD(T)/CBS method, which is deemed to give the most accurate estimates of Eint in 1–5, confirms that the interaction between SnX2 and C6H6 should be classified as weak, with the Eint values between −10.0 and −11.2 kcal/mol. Comparing the CCSD(T)/CBS results with the ωB97X ones, we see that the former indicate a more diversified strength of the interaction in the investigated series of complexes. The SnCl2 molecule is bound strongest to the C6H6 molecule, whereas the bonding of SnH2 to C6H6 turns out to be particularly weak. For the complexes containing the tin(II) dihalides, no monotonous regularity in their CCSD(T)/CBS Eint values is found while X becomes heavier and heavier.

Interaction energy decomposition

The next step of this work is to characterize the physical nature of the interaction between SnX2 and C6H6 using the SAPT method. We first focus on the DFT-SAPT interaction energy terms calculated for 1–5 and listed in Table 3. For all five complexes their electrostatic first-order term E(1)elst is negative, which can be naively understood as a result of the attraction between the π-cloud and the positively-charged Sn atom (its QTAIM charge ranges from 0.86 to 1.49 au in 1–5). The absolute values of E(1)elst are always noticeably smaller than the corresponding values of the first-order exchange term E(1)exch. The magnitude of the second-order induction E(2)ind (SnX2 → C6H6) is several times larger than its E(2)ind (SnX2 ← C6H6) analog. It means that the C6H6 molecule is easily polarized by the SnX2 molecule, whereas the polarization in the opposite direction is significantly less pronounced. The E(2)ind(SnX2 ← C6H6) term of each complex is practically counterbalanced by the corresponding E(2)exch ‐ ind (SnX2 ← C6H6) term, while E(2)ind(SnX2 → C6H6) is quenched up to ca. 66 % by its exchange counterpart. An even smaller percentage quenching of E(2)disp is attributed to E(2)exch ‐ disp. The δEHF term destabilizes all five complexes. This term collectively gathers mostly third- and higher-order induction and exchange-induction contributions. The values of δEHF decrease gradually in the sequence from 1 to 5, that is, with growing dSn···C distance. This indicates that the higher-order effects become increasingly important at shorter distances. Even though the inclusion of δEHF into the DFT-SAPT Eint values leads to the underestimation of the strength of the interaction in 1–5, the presence of δEHF is more beneficial for the accuracy of Eint than omitting this term. This is a well-documented feature of SAPT computations involving pseudopotentials [70].

Table 3.

SAPT interaction energy terms calculated using the DFT-SAPT variant

| Energy term | Complex | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| E (1)exch | 17.2 | 19.0 | 20.4 | 20.5 | 20.4 |

| E (1)elst | −12.0 | −14.0 | −14.1 | −14.0 | −13.7 |

| E (2)ind(SnX2 → C6H6) | −31.7 | −28.1 | −25.8 | −24.6 | −22.4 |

| E (2)exch ‐ ind(SnX2 → C6H6) | 21.1 | 18.5 | 17.0 | 16.3 | 14.5 |

| E (2)ind(SnX2 ← C6H6) | −4.9 | −6.0 | −7.2 | −7.8 | −8.7 |

| E (2)exch ‐ ind(SnX2 ← C6H6) | 4.7 | 5.8 | 7.0 | 7.6 | 8.6 |

| E (2)disp | −11.5 | −11.6 | −13.4 | −13.9 | −14.4 |

| E (2)exch ‐ disp | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 3.0 |

| δE HF | 6.0 | 4.1 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 2.4 |

All values in kcal/mol

Next, let us examine the relative importance of four principal components of Eint in order to establish the physical origin of the interaction between SnX2 and C6H6. Table 4 summarizes the results of grouping either HF-SAPT or DFT-SAPT interaction energy terms into four principal components. We now take a closer look at the DFT-SAPT components but the findings we make using these components are also valid for the HF-SAPT components.

Table 4.

Four principal components of SAPT interaction energies calculated using the HF-SAPT and DFT-SAPT variants

| Principal component | Complex | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| E HF ‐ SAPTexch | 18.7 | 19.3 | 21.2 | 21.3 | 21.1 |

| E HF ‐ SAPTelst | −14.0 (46.2) |

−16.1 (48.8) |

−16.2 (46.4) |

−16.0 (45.7) |

−15.7 (45.1) |

| E HF ‐ SAPTind | −6.8 (22.6) |

−7.7 (23.5) |

−7.9 (22.6) |

−7.9 (22.4) |

−7.5 (21.6) |

| E HF ‐ SAPTdisp | −9.5 (31.2) |

−9.1 (27.7) |

−10.8 (31.0) |

−11.2 (31.8) |

−11.6 (33.3) |

| E DFT ‐ SAPTexch | 17.2 | 19.0 | 20.4 | 20.5 | 20.4 |

| E DFT ‐ SAPTelst | −12.0 (46.1) |

−14.0 (48.4) |

−14.1 (45.9) |

−14.0 (45.1) |

−13.7 (44.6) |

| E DFT ‐ SAPTind | −4.8 (18.3) |

−5.7 (19.8) |

−6.0 (19.4) |

−6.0 (19.3) |

−5.6 (18.3) |

| E DFT ‐ SAPTdisp | −9.3 (35.6) |

−9.2 (31.8) |

−10.7 (34.7) |

−11.0 (35.6) |

−11.4 (37.1) |

The percentage share of individual attractive components in the total attraction between SnX2 and C6H6 is given in parentheses

Energy components in kcal/mol

For all five complexes, the DFT-SAPT decomposition of their Eint energies yields three attractive components, namely EDFT ‐ SAPTelst, EDFT ‐ SAPTind and EDFT ‐ SAPTdisp. These three components provide sufficient stabilization to overcome the repulsive exchange component, and therefore, the resultant Eint values are negative (see Table 2). Among the attractive components, electrostatics represents the most energetically favorable contribution, followed by dispersion and then by induction. The EDFT ‐ SAPTelst component provides slightly less than half of the total attraction between SnX2 and C6H6. However, this component does not surpass the EDFT ‐ SAPTexch one, and in consequence, the total contribution from the first-order DFT-SAPT energy terms remains repulsive. Therefore, the stability of 1–5 is due to the second- and higher-order DFT-SAPT energy terms, that are included in the EDFT ‐ SAPTind and EDFT ‐ SAPTdisp components. Of the two components, the latter plays the more important role. In relative terms, dispersion accounts for roughly one third of the total attraction between SnX2 and C6H6. The relevant role of the dispersion energy often occurs for complexes containing large, diffuse electron clouds, such as the π-electron system of benzene in our case. The stabilization arising mainly from the combined effect of electrostatics and dispersion has recently been detected also for some other benzene complexes, e.g. with HCN [71].

The absolute values of EDFT ‐ SAPTind essentially increase with the growing atomic number of the X atoms. However, there is a noticeable decrease of the magnitude of EDFT ‐ SAPTind when one goes from 4 to 5. This results from the usage of a pseudopotential for the core electrons of the I atoms. For 2–5, the magnitude of EDFT ‐ SAPTdisp and simultaneously the relative importance of this component increase while the halogen atoms get heavier. This is consistent with the growing polarizability of tin(II) dihalides [72]. In contrast to EDFT ‐ SAPTdisp, the other two attractive components of Eint show a diminishing relative importance while moving throughout the series from 2 to 5.

Topological analysis of electron density

Complementary information about the interaction between SnX2 and C6H6 can be obtained from the QTAIM topological analysis of the electron density ρ in 1–5. The molecular graph determined for 1 is shown in Fig. 2. It is evident from the graph that there is a single bond path (BP) linking the Sn atom and the adjacent C atom of the C6H6 molecule. Such a feature of the topology of ρ is common to all five complexes 1–5. This suggests that the formation of a Sn · · · C contact between the Sn atom and its nearest neighboring C atom of C6H6 is associated with the existence of a bonding interaction between these atoms [73]. The existence of the BP linking the Sn atom and its nearest neighboring C atom also indicates that, from the perspective of the QTAIM, the complexes 1–5 should be described as η1 complexes.

Fig. 2.

Molecular graph for 1. BCPs are denoted by small red circles, while the only ring critical point is marked by a small yellow circle. All atoms are colored the same as in Fig. 1

The topological properties of ρ at the bond critical point (BCP) on the BP of the Sn · · · C contact in 1–5 provide a more detailed QTAIM characteristics of the interaction between SnX2 and C6H6. The values of several such properties are collected in Table 5. The values of ρ decrease with growing dSn···C distance. The relationship between ρ and dSn···C exhibits a good linear reverse correlation, with the respective coefficient of determination R2 being equal to 0.96. It is due to the fact that the range of the dSn···C distances found for 1–5 is very narrow. For a broader range of distances a non-linear relationship should be rather expected, as it was demonstrated for other noncovalent interactions [74, 75]. The values of ρ at the BCP of the Sn · · · C contact in 1–5 are much smaller than typical ρ values at the BCP of a covalent Sn-C bond (e.g. 0.099 and 0.106 au for the Sn-C bonds of Sn(CH3)2 and Sn(CH3)4, respectively). Furthermore, the ρ values in Table 5 are smaller than those found for Sn · · · C contacts in the solid-state structure of dicationic tin-toluene complex [Sn(C7H8)3]2+ [13]. It is accompanied by an elongation of the Sn · · · C contact in 1–5 compared to the contacts of [Sn(C7H8)3]2+. The values of the Laplacian of the electron density ∇2ρ in 1–5 are positive, which means that the charge density is locally depleted at the BCP relative to the neighboring points in space and, in consequence, it is locally concentrated in the basins of the Sn and C atoms of the contact. The total energy density H, which is the sum of the electron kinetic energy density G and the electron potential energy density V, adopts the negative sign but the values of H are very close to zero. This may suggest that there is only a minor covalent factor contributing to the nature of the interaction between SnX2 and C6H6. Moreover, the low values of ρ and ∇2ρ > 0, together with –V/G > 1 and –λ1/λ3 < < 1, provide evidence for the lack of any appreciable covalency [17, 74]. The aforementioned criteria indicate that this interaction should be classed as the closed-shell, noncovalent interaction [17, 74]. The –λ1/λ3 criterion of the nature of interaction is calculated using the lowest λ1 and highest λ3 eigenvalues of the Hessian matrix of ρ. The QTAIM characteristics of the Sn · · · C bonding interaction in 1–5 is essentially similar to that found previously for metal-ligand bonds in some complexes of Mn [76, 77] and Zn [78].

Table 5.

QTAIM properties at the BCP on the BP linking the Sn atom and the adjacent C atom in each of the complexes 1–5

| Property | Complex | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| ρ · 102 | 1.776 | 1.688 | 1.660 | 1.617 | 1.557 |

| ∇2 ρ · 102 | 3.946 | 3.425 | 3.272 | 3.195 | 3.092 |

| G · 103 | 10.330 | 8.828 | 8.426 | 8.147 | 7.777 |

| V · 103 | −10.795 | −9.094 | −8.674 | −8.306 | −7.825 |

| H · 104 | −4.648 | −2.661 | −2.475 | −1.587 | −0.479 |

| –V/G | 1.045 | 1.030 | 1.029 | 1.019 | 1.006 |

| –λ 1/λ 3 | 0.185 | 0.228 | 0.227 | 0.225 | 0.221 |

All values in au, except for the –V/G and –λ 1/λ 3 ratios that are dimensionless

The standard QTAIM characterization presented above can be supplemented by the analysis of the NCI visualization index. The plots showing the NCI isosurfaces detected for 1, 2 and 5 are presented in Fig. 3. As can be seen in these plots, the interaction between SnX2 and C6H6 in the complexes is characterized by a blue isosurface located between the Sn atom and its nearest neighboring C atom. The region delineated by this isosurface illustrates the occurrence of the attractive interaction between SnX2 and C6H6. For the complexes containing the tin(II) dihalides, additional isosurfaces representing the interaction between SnX2 and C6H6 appear. Such isosurfaces are located between the Sn atom and the more distant C atoms of C6H6. These isosurfaces are colored in green in Fig. 3 and they are associated with the occurrence of an extremely weak, repulsive interaction. Some other NCI isosurfaces denoting the existence of a secondary attractive interaction can in turn be found between the I atoms and their nearest neighboring H atoms in 5. One may speculate that these isosurfaces can be ascribed to the occurrence of a very weak H-bonding, although no BP has been detected between the I and H atoms, and the distance of 3.651 Å between these atoms exceeds the sum of their van der Waals radii.

Fig. 3.

NCI isosurfaces for 1, 2 and 5. The isosurfaces are plotted with a reduced density gradient value of 0.35 au and they are colored from blue to red according to sign(λ 2)ρ ranging from −0.02 to 0.02 au. The colors denoting the H, C and Sn atoms are the same as in Fig. 1. The atoms of F and I are drawn in green and violet, respectively

Electron density deformations and charge transfer

In the subsection presented above, the complexes have been examined mainly from the perspective of their ρ itself. Now, the comparison of this ρ with the electron densities of non-interacting SnX2 and C6H6 fragments is made in order to determine how the electron density adjusts to the interaction between SnX2 and C6H6. Such a comparison can conveniently be presented in the form of an electron density difference plot, as it is shown in Fig. 4 for 1, 2 and 5. For each of these complexes, its electron density difference has been computed as the difference between the ρ of the whole complex and the sum of the densities of individual SnX2 and C6H6 fragments in their geometries taken from the complex. The regions delineated by blue isosurfaces in Fig. 4 illustrate an increase in ρ arising from the interaction, while the red regions determine where ρ is reduced. The most relevant changes in the ρ distribution are detected for the Sn · · · C contact and its spatially closest neighborhood. There is a region of ρ reduction immediately below the Sn atom of SnX2, whereas an increase in ρ is observed above this atom. In other words, the ρ distribution around the Sn atom becomes polarized toward the π-electron cloud of C6H6 upon complexation. The regions of growing ρ are found around the X atoms and the ρ deformation around these atoms is enhanced while moving from X = I to X = F, that is, with the increasing electronegativity of X. The distribution of ρ within the C6H6 molecule also undergoes some changes upon the complexation with SnX2. The most prominent change can be perceived above the C atom involved in the contact with the Sn atom. The vast blue region of increased ρ spreads over the part of the adjacent C-H bond. This is accompanied by several regions of ρ loss around the H atoms on the periphery of C6H6.

Fig. 4.

Plots of the electron density difference calculated for 1, 2 and 5. The blue and red isosurfaces are plotted with contour values of 0.001 and −0.001 au, respectively. The colors coding individual elements are the same as in Fig. 3

An essential aspect of the interaction between SnX2 and C6H6 is the magnitude of the charge transfer that possibly appears as a result of complexation. The charge transfer between SnX2 and C6H6 is estimated here using the QTAIM atomic charges calculated for 1–5. The QTAIM charges of atoms constituting the SnX2 fragment of the complexes are summed up, yielding the overall magnitude of charge transferred between SnX2 and C6H6. The magnitude of the charge transfer estimated in that manner adopts very small values, from 0.0388 au for 5 to 0.0578 au for 2. The complexes containing the tin(II) dihalides show a gradual decrease in the magnitude of charge transfer while going throughout the series from 2 to 5. For these complexes there is a strong linear association between the decreasing magnitude of charge transfer and the increasing value of dSn···C (the resulting inverse correlation between these two quantities is quantitatively characterized by R2 = 0.99). The charge transfer in 1 is estimated to be 0.0415 au. The formation of all five complexes leads to a small flow of electron charge from the C6H6 molecule to the SnX2 molecule. Thus, the SnX2 fragment of 1–5 bears a slight negative charge, from −0.0388 to −0.0578 au. The detected very small charge transfer and its direction may point at the existence of a very weak donor-acceptor π → Sn contribution to the interaction in 1–5. It would be in line with the results of a previous computational study based on the NBO approach [20]. In that study, an electron donation from the π-type NBO orbitals of C6H6 to the formally empty p-NBO orbital on the Sn atom of SnX2 was indeed detected but the calculated charge transfers from C6H6 to SnX2 were even smaller than those reported here.

Analysis of vibrational frequencies

The formation of 1–5 introduces some characteristic changes in the frequencies of vibrations occurring for the SnX2 and C6H6 fragments of the complexes. Table 6 presents shifts in the frequencies of three vibrations upon complex formation. The three vibrations include asymmetrical and symmetrical stretching frequencies of Sn-X bonds (υas,Sn-X and υs,Sn-X) and out-of-plane deformation vibrations of C-H bonds in the C6H6 ring (δC-H). The frequencies of these vibrations have been computed within the quantum harmonic oscillator approximation at the ωB97X/aug-cc-pVTZ(-PP) level of theory. They have not been scaled.

Table 6.

Shifts in vibrational frequencies of 1–5 as the result of complex formation

| Frequency shift | Complex | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Δυ as,Sn-X | −41 | −35 (−29) |

−21 | −15 | −14 |

| Δυ s,Sn-X | −38 | −32 (−29) |

−19 | −12 | −10 |

| Δδ C-H | 13 | 17 (19) |

19 | 19 | 17 |

Available experimental results taken from Ref. [52] are given in parentheses

All values in cm−1

The negative values of Δυas,Sn-X and Δυs,Sn-X shown in Table 6 indicate that small red shifts are observed for the frequencies of Sn-X stretching vibrations. The occurrence of these red shifts is associated with a minor elongation of Sn-X bonds upon complexation (see Table S6). The elongation of Sn-X bonds and the accompanying red shifts of Sn-X stretching frequencies can be roughly explained by the charge transfers between SnX2 and C6H6. As it was discussed in the previous subsection, the SnX2 fragment of the complexes bears a slight negative charge and the plots of the electron density difference show regions of electron accumulation around the Sn and X atoms upon complexation. Such a charge transfer contributes to the red shifts. The NBO results reported in Ref. [20] confirm the existence of the charge transfer from the π-type orbitals of C6H6 to the empty orbitals of SnX2. Additionally, the charge transfer involving the π-type orbitals is reflected in the structural properties of the C6H6 ring. Our calculations reveal that the C-C bonds are elongated by ca. 0.002 Å upon the formation of SnX2 · · · C6H6. A region of growing ρ around the C atom adjacent to Sn has been clearly seen in Fig. 4. This implies that at the same time there is a reverse transfer toward C6H6, which also facilitates the red shifts. The NBO analysis has however established that the back-donation toward the π*-orbitals of C6H6 is negligible in comparison to the transfer toward the orbitals of SnX2 [20].

The calculated Δυas,Sn-X, Δυs,Sn-X and ΔδC-H of 2 can be compared with the corresponding experimental data taken from Ref. [52]. The calculated values demonstrate good agreement with the experimental data. The reliability of the presented computational predictions of shifts in vibrational frequencies can be further proven through the inclusion of additional complexes in this study. Two additional complexes composed of SnF2 and chlorobenzene or toluene have been considered because their Δυas,Sn-F, Δυs,Sn-F and ΔδC-H shifts were previously determined experimentally [52]. The results obtained for these two additional complexes are presented in detail in section S3. Suffice it to say here that the calculated shifts in the Sn-F and C-H vibrational frequencies of 2 and two additional complexes are in good agreement with experiment. Moreover, the calculated shifts of υas,Sn-F and υs,Sn-F reproduce the experimentally established trend in the magnitude of these shifts [52].

Conclusions

In this work a variety of quantum-chemical methods have been used to provide an insight into the intermolecular interaction occurring in the complexes of SnX2 with C6H6. By analyzing the results of energy and electron density topology calculations, we conclude with the following remarks.

The complexes are rather weakly bound and the Eint energy between SnX2 and C6H6 turns out to be similar for all five complexes. A very small destabilizing effect associated with changes in the geometries of SnX2 and C6H6 appears during the formation of each complex. This effect does not exceed 4 % of the absolute values of Eint.

The effects of electron correlation play a vital role in the proper description of the interaction in the five complexes. Among the DFT methods, those belonging to older DFT generations fail badly: both severe under- and overestimations of Eint are possible. The inclusion of the D3(BJ) correction improves their performance, but it tends to overestimate the role of long-range electron correlation. Newer density functionals without empirical dispersion correction (M06-2X and ωB97X) acquit themselves reasonably well.

The SAPT analysis reveals that the electrostatics is the dominant attractive component of Eint for all five complexes. However, the Eelst component is compensated by the Eexch component, and therefore, the stabilization of the complexes is determined to a great extent by the second-order component that is accountable for dispersion.

Based on the QTAIM and NCI results, the interaction between SnX2 and C6H6 can be classified as a closed-shell, noncovalent and attractive interaction. The formation of the complexes polarizes the electron density around the Sn atom toward the π-cloud of C6H6.

By integrating the electron density of the complexes over their QTAIM atomic basins, we have deduced a very small charge transfer from C6H6 to SnX2 for all five complexes.

The calculated shifts in the frequencies of Sn-X and C-H vibrations agree well with the available experimental data. The relatively small shifts of these vibrational frequencies upon complexation confirm that the interaction between SnX2 and C6H6 is rather weak and there is no appreciable change in the inner geometries of interacting SnX2 and C6H6.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(DOC 5.55 mb)

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by PL-Grid Infrastructure.

References

- 1.Haiduc I, Edelmann FT. Supramolecular Organometallic Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyer F, Khan FA, Armentrout PB. Thermochemistry of transition metal benzene complexes: Binding energies of M(C6H6)x+ (x = 1,2) for M = Ti to Cu. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:9740–9748. doi: 10.1021/ja00143a018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurikawa T, Takeda H, Hirano M, Judai K, Arita T, Nagao S, Nakajima A, Kaya K (1999) Electronic properties of organometallic metal-benzene complexes [Mn(benzene)m (M = Sc–Cu)]. Organometallics 18:1430–1438

- 4.Han S, Singh NJ, Kang TY, Choi K-W, Choi S, Baek SJ, Kim KS, Kim SK. Aromatic π–π interaction mediated by a metal atom: Structure and ionization of the bis(η6-benzene)chromium–benzene cluster. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2010;12:7648–7653. doi: 10.1039/b923929d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunner H, Oescheya R, Nuber B. Optically active transition metal complexes. Part 108. Synthesis, crystal structure and properties of a novel “quasi-meso” dinuclear η6-benzene-ruthenium(II) complex with chiral salicylaldiminato ligands. J Organomet Chem. 1996;518:47–53. doi: 10.1016/0022-328X(96)06210-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang J, Smith JR, Luo Y, Grennberg H, Ottosson H. Multidecker bis(benzene)chromium: Opportunities for design of rigid and highly flexible molecular wires. J Phys Chem C. 2011;115:785–790. doi: 10.1021/jp109782q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haghiri A, Lerner H-W, Bats JW. Tricarbonyl[η6-1-methyl-4-(trimethylsilyl)benzene]chromium(0) Acta Cryst E. 2007;63:1133–1134. doi: 10.1107/S1600536807012159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidbaur H, Schier A. π-Complexation of post-transition metals by neutral aromatic hydrocarbons: The road from observations in the 19th century to new aspects of supramolecular chemistry. Organometallics. 2008;27:2361–2395. doi: 10.1021/om701044e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haiduc I, Tiekink ERT, Zukerman-Schpector J. Intermolecular tin · · · π-aryl interactions: Fact or artifact? A new bonding motif for supramolecular self-assembly in organotin compounds. In: Gielen M, Davies AG, Pannell KH, Tiekink ERT, editors. Tin Chemistry: Fundamentals, Frontiers, and Applications. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2008. pp. 392–412. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neumann WP. Germylenes and stannylenes. Chem Rev. 1991;91:311–334. doi: 10.1021/cr00003a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zabula AV, Hahn FE. Mono- and bidentate benzannulated N-heterocyclic germylenes, stannylenes and plumbylenes. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2008;2008:5165–5179. doi: 10.1002/ejic.200800866. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mansell SM, Russell CA, Wass DF. Synthesis and structural characterization of tin analogues of N-heterocyclic carbenes. Inorg Chem. 2008;47:11367–11375. doi: 10.1021/ic801479g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schäfer A, Winter F, Saak W, Haase D, Pöttgen R, Müller T. Stannylium ions, a tin(II) arene complex, and a tin dication stabilized by weakly coordinating anions. Chem Eur J. 2011;17:10979–10984. doi: 10.1002/chem.201101938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li J, Schenk C, Winter F, Scherer H, Trapp N, Higelin A, Keller S, Pöttgen R, Krossing I, Jones C. Weak arene stabilization of bulky amido-germanium(II) and tin(II) monocations. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:9557–9561. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeziorski B, Moszyński R, Szalewicz K. Perturbation theory approach to intermolecular potential energy surfaces of van der Waals complexes. Chem Rev. 1994;94:1887–1930. doi: 10.1021/cr00031a008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szalewicz K. Symmetry-adapted perturbation theory of intermolecular forces. WIREs Comput Mol Sci. 2012;2:254–272. doi: 10.1002/wcms.86. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bader RFW. Atoms in Molecules: A Quantum Theory. Oxford, UK: Clarendon; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson ER, Keinan S, Mori-Sánchez P, Contreras-García J, Cohen AJ, Yang W. Revealing noncovalent interactions. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:6498–6506. doi: 10.1021/ja100936w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matczak P, Wojtulewski S. Performance of Møller-Plesset second-order perturbation theory and density functional theory in predicting the interaction between stannylenes and aromatic molecules. J Mol Model. 2015;21:41. doi: 10.1007/s00894-015-2589-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Broeckaert L, Geerlings P, Růžička A, Willem R, De Proft F. Can aromatic π-clouds complex divalent germanium and tin compounds? A DFT study. Organometallics. 2012;31:1605–1617. doi: 10.1021/om100903h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chai J-D, Head-Gordon M. Systematic optimization of long-range corrected hybrid density functionals. J Chem Phys. 2008;128:084106. doi: 10.1063/1.2834918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunning TH., Jr Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. I. The atoms boron through neon and hydrogen. J Chem Phys. 1989;90:1007–1023. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peterson KA. Systematically convergent basis sets with relativistic pseudopotentials. I. Correlation consistent basis sets for the post-d group 13–15 elements. J Chem Phys. 2003;119:11099–11112. doi: 10.1063/1.1622923. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Metz B, Stoll H, Dolg M. Small-core multiconfiguration-Dirac–Hartree–Fock-adjusted pseudopotentials for post-d main group elements: Application to PbH and PbO. J Chem Phys. 2000;113:2563–2569. doi: 10.1063/1.1305880. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slater JC. The Self-Consistent Field for Molecular and Solids, Quantum Theory of Molecular and Solids. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vosko SH, Wilk L, Nusair M. Accurate spin-dependent electron liquid correlation energies for local spin density calculations: A critical analysis. Can J Phys. 1980;58:1200–1211. doi: 10.1139/p80-159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Becke AD. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys Rev A. 1988;38:3098–3100. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevA.38.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee C, Yang W, Parr RG. Development of the Colle–Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys Rev B. 1988;37:785–789. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Becke AD. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:5648–5642. doi: 10.1063/1.464913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao Y, Truhlar DG. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: Two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor Chem Acc. 2008;120:215–241. doi: 10.1007/s00214-007-0310-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hartree DR. The wave mechanics of an atom with a non-Coulomb central field. Part I: Theory and methods. Proc Cambridge Philos Soc. 1928;24:89–110. doi: 10.1017/S0305004100011919. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fock V (1930) Näherungsmethode zur Lösung des quantenmechanischen Mehrkörperproblems. Z Phys 61:126–148

- 33.Møller C, Plesset MS. Note on an approximation treatment for many-electron systems. Phys Rev. 1934;46:618–622. doi: 10.1103/PhysRev.46.618. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grimme S. Improved second-order Møller-Plesset perturbation theory by separate scaling of parallel- and antiparallel-spin pair correlation energies. J Chem Phys. 2003;118:9095–9102. doi: 10.1063/1.1569242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gauss J, et al. Coupled-cluster theory. In: Schleyer PR, Allinger NL, Clark T, et al., editors. Encyclopedia of Computational Chemistry. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 1998. pp. 615–636. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boys SF, Bernardi F. The calculation of small molecular interactions by the differences of separate total energies. Some procedures with reduced errors. Mol Phys. 1970;19:553–566. doi: 10.1080/00268977000101561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burns LA, Marshall MS, Sherrill CD. Comparing counterpoise-corrected, uncorrected, and averaged binding energies for benchmarking noncovalent interactions. J Chem Theory Comput. 2014;10:49–57. doi: 10.1021/ct400149j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Montgomery JA, Jr, Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark M, Heyd JJ, Brothers E, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Keith T, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell A, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam JM, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas O, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski J, Fox DJ. Gaussian 09 D.01. Wallingford CT: Gaussian, Inc; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahlrichs R, Armbruster MK, Bachorz RA, Bär M, Baron HP, Bauernschmitt R, Bischoff FA, Böcker S, Crawford N, Deglmann P, Della Sala F, Diedenhofen M, Ehrig M, Eichkorn K, Elliott S, Friese D, Furche F, Glöß A, Haase F, Häser M, Hättig C, Hellweg A, Höfener S, Horn H, Huber C, Huniar U, Kattannek M, Klopper W, Köhn A, Kölmel C, Kollwitz M, May K, Nava P, Ochsenfeld C, Öhm H, Pabst M, Patzelt H, Rappoport D, Rubner O, Schäfer A, Schneider U, Sierka M, Tew DP, Treutler O, Unterreiner B, von Arnim M, Weigend F, Weis P, Weiss H, Winter N (2014) TURBOMOLE 6.6. A development of University of Karlsruhe and Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe GmbH, 1989–2007, TURBOMOLE GmbH, since 2007, Karlsruhe, Germany, http://www.turbomole.com

- 40.Williams HL, Chabalowski CF. Using Kohn–Sham orbitals in symmetry-adapted perturbation theory to investigate intermolecular interactions. J Phys Chem A. 2001;105:646–659. doi: 10.1021/jp003883p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jansen G, Hesselmann A. Comment on “Using Kohn − Sham orbitals in symmetry-adapted perturbation theory to investigate intermolecular interactions”. J Phys Chem A. 2001;105:11156–11157. doi: 10.1021/jp0112774. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grüning M, Gritsenko OV, van Gisbergen SJA, Baerends EJ. Shape corrections to exchange-correlation potentials by gradient-regulated seamless connection of model potentials for inner and outer region. J Chem Phys. 2001;114:652–660. doi: 10.1063/1.1327260. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adamo C, Barone V. Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: The PBE0 model. J Chem Phys. 1999;110:6158–6170. doi: 10.1063/1.478522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Werner H-J, Knowles PJ, Knizia G, Manby FR, Schütz M, Celani P, Korona T, Lindh R, Mitrushenkov A, Rauhut G, Shamasundar KR, Adler TB, Amos RD, Bernhardsson A, Berning A, Cooper DL, Deegan MJO, Dobbyn AJ, Eckert F, Goll E, Hampel C, Hesselmann A, Hetzer G, Hrenar T, Jansen G, Köppl C, Liu Y, Lloyd AW, Mata RA, May AJ, McNicholas SJ, Meyer W, Mura ME, Nicklass A, O’Neill DP, Palmieri P, Peng D, Pflüger K, Pitzer R, Reiher M, Shiozaki T, Stoll H, Stone AJ, Tarroni R, Thorsteinsson T, Wang M (2012) MOLPRO 2012.1. University College Cardiff Consultants Limited, Cardiff, UK, http://www.molpro.net

- 45.Werner H-J, Knowles PJ, Knizia G, Manby FR, Schütz M. MOLPRO: A general-purpose quantum chemistry program package. WIREs Comput Mol Sci. 2012;2:242–253. doi: 10.1002/wcms.82. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keith TA. AIMAll (Version 14.11.23) USA: TK Gristmill Software, Overland Park KS; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lu T, Chen F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J Comput Chem. 2012;33:580–592. doi: 10.1002/jcc.22885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Silvi B, Savin A. Classification of chemical bonds based on topological analysis of electron localization functions. Nature. 1994;371:683–686. doi: 10.1038/371683a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jmol: An open-source Java viewer for chemical structures in 3D. http://www.jmol.org

- 50.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD – Visual Molecular Dynamics. J Mol Graphics. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alvarez S. A cartography of the van der Waals territories. Dalton Trans. 2013;42:8617–8636. doi: 10.1039/c3dt50599e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boganov SE, Egorov MP, Nefedov OM. Study of complexation between difluorostannylene and aromatics by matrix IR spectroscopy. Russ Chem Bull. 1999;48:98–103. doi: 10.1007/BF02494408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Soteras I, Orozco M, Luque FJ. Induction effects in metal cation–benzene complexes. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2008;10:2616–2624. doi: 10.1039/b719461g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khanmohammadi A, Raissi H, Mollania F, Hokmabadi L. Molecular structure and bonding character of mono and divalent metal cations (Li+, Na+, K+, Be2+, Mg2+, and Ca2+) with substituted benzene derivatives: AIM, NBO, and NMR analyses. Struct Chem. 2014;25:1327–1342. doi: 10.1007/s11224-014-0405-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nziko VPN, Scheiner S. S · · · π Chalcogen bonds between SF2 or SF4 and C − C multiple bonds. J Phys Chem A. 2015;119:5889–5897. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpca.5b03359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saberinasab M, Salehzadeh S, Maghsoud Y, Bayat M. The significant effect of electron donating and electron withdrawing substituents on nature and strength of an intermolecular Se · · · π interaction. A theoretical study. Comput Theoret Chem. 2016;1078:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.comptc.2015.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kurth S, Perdew JP, Blaha P. Molecular and solid-state tests of density functional approximations: LSD, GGAs, and meta-GGAs. Int J Quantum Chem. 1999;75:889–909. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-461X(1999)75:4/5<889::AID-QUA54>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grimme S, Ehrlich S, Goerigk L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J Comput Chem. 2011;32:1456–1465. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schneebeli ST, Bochevarov AD, Friesner RA. Parameterization of a B3LYP specific correction for noncovalent interactions and basis set superposition error on a gigantic data set of CCSD(T) quality noncovalent interaction energies. J Chem Theory Comput. 2011;7:658–668. doi: 10.1021/ct100651f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van der Wijst T, Fonseca Guerra C, Swart M, Bickelhaupt FM, Lippert B. A ditopic ion-pair receptor based on stacked nucleobase quartets. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:3285–3287. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fonseca Guerra C, van der Wijst T, Poater J, Swart M, Bickelhaupt FM. Adenine versus guanine quartets in aqueous solution: Dispersion-corrected DFT study on the differences in π-stacking and hydrogen-bonding behavior. Theor Chem Acc. 2010;125:245–252. doi: 10.1007/s00214-009-0634-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang W, Truhlar DG, Tang M. Tests of exchange-correlation functional approximations against reliable experimental data for average bond energies of 3d transition metal compounds. J Chem Theory Comput. 2013;9:3965–3977. doi: 10.1021/ct400418u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Matczak P, Łukomska M. Assessment of various density functionals for intermolecular N → Sn interactions: The test case of trimethyltin cyanide dimer. Comput Theoret Chem. 2014;1036:31–43. doi: 10.1016/j.comptc.2014.02.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Matczak P. Assessment of various density functionals for intermolecular N → Sn interactions: The test case of poly(trimethyltin cyanide) Comput Theoret Chem. 2015;1051:110–122. doi: 10.1016/j.comptc.2014.10.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao Y, Truhlar DG. Density functionals for noncovalent interaction energies of biological importance. J Chem Theory Comput. 2007;3:289–300. doi: 10.1021/ct6002719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hohenstein EG, Sherrill CD. Wavefunction methods for noncovalent interactions. WIREs Comput Mol Sci. 2012;2:304–326. doi: 10.1002/wcms.84. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Parker TM, Burns LA, Parrish RM, Ryno AG, Sherrill CD. Levels of symmetry adapted perturbation theory (SAPT). I. Efficiency and performance for interaction energies. J Chem Phys. 2014;140 doi: 10.1063/1.4867135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cybulski SM, Chałasiński G, Moszyński R. On decomposition of second-order Møller-Plesset supermolecular interaction energy and basis set effects. J Chem Phys. 1990;92:4357–4363. doi: 10.1063/1.457743. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cybulski SM, Lytle ML. The origin of deficiency of the supermolecule second-order Møller-Plesset approach for evaluating interaction energies. J Chem Phys. 2007;127:141102. doi: 10.1063/1.2795693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Patkowski K, Szalewicz K. Frozen core and effective core potentials in symmetry-adapted perturbation theory. J Chem Phys. 2007;127:164103. doi: 10.1063/1.2784391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Riley KE, Ford CL, Jr, Demouchet K. Comparison of hydrogen bonds, halogen bonds, C-H · · · π interactions, and C-X · · · π interactions using high-level ab initio methods. Chem Phys Lett. 2015;621:165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2014.12.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kalugina YN, Thakkar AJ. Electric properties of stannous and stannic halides: How good are the experimental values? Chem Phys Lett. 2015;626:69–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2015.02.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bader RFW. A bond path: A universal indicator of bonded interactions. J Phys Chem A. 1998;102:7314–7323. doi: 10.1021/jp981794v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Espinosa E, Alkorta I, Elguero J, Molins E. From weak to strong interactions: A comprehensive analysis of the topological and energetic properties of the electron density distribution involving X–H · · · F–Y systems. J Chem Phys. 2002;117:5529–5542. doi: 10.1063/1.1501133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Grabowski SJ, Leszczynski J. The enhancement of X–H · · · π hydrogen bond by cooperativity effects — Ab initio and QTAIM calculations. Chem Phys. 2009;355:169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphys.2008.12.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bianchi R, Gervasio G, Marabello D. Experimental electron density analysis of Mn2(CO)10: Metal-metal and metal-ligand bond characterization. Inorg Chem. 2000;39:2360–2366. doi: 10.1021/ic991316e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Van der Maelen JF, Cabeza JA. QTAIM analysis of the bonding in Mo − Mo bonded dimolybdenum complexes. Inorg Chem. 2012;51:7384–7391. doi: 10.1021/ic300845g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cukrowski I, de Lange JH, Mitoraj M. Physical nature of interactions in ZnII complexes with 2,2′-bipyridyl: Quantum theory of atoms in molecules (QTAIM), interacting quantum atoms (IQA), noncovalent interactions (NCI), and extended transition state coupled with natural orbitals for chemical valence (ETS-NOCV) comparative studies. J Phys Chem A. 2014;118:623–637. doi: 10.1021/jp410744x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC 5.55 mb)