Abstract

Objectives

The association of volunteering with well-being has been found in previous research, but mostly among older people. The aim of this study was to examine the association of volunteering with mental well-being among the British population across the life course.

Design

British Household Panel Survey, a population-based longitudinal study.

Setting

UK.

Participants

66 343 observations (person-years).

Main outcome measures

Mental well-being was measured by using the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12 or GHQ); high values denote high mental disorder. Four groups of volunteering participation were created: frequent (once a week), infrequent (once a month/several times a year), rare (once or less a year) and never. Multilevel linear models were used to analyse variations in mental well-being over the life course by levels of volunteering.

Results

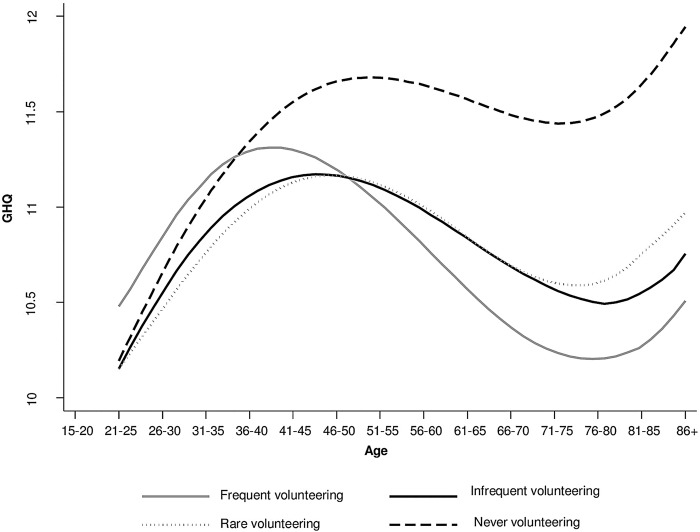

When not considering age, those who engaged in volunteering regularly appeared to experience higher levels of mental well-being than those who never volunteered. To explore the association of volunteering with the GHQ across the life course, interaction terms were fitted between age and volunteering. The interactions were significant, demonstrating that these associations vary by age. The association between volunteering and well-being did not emerge during early adulthood to mid-adulthood, instead becoming apparent above the age of 40 years and continuing up to old age. Moreover, in early adulthood, the absence of engagement in voluntary activity was not related to mental well-being, but GHQ scores for this group increased sharply with age, levelling off after the age of 40 and then increasing again above the age of 70 years. The study also indicates variation in GHQ scores (65%) within individuals across time, suggesting evidence of lifecourse effects.

Conclusions

We conclude that volunteering may be more meaningful for mental well-being at some points of time in the life course.

Keywords: volunteering, GHQ-12, longitudinal study, Britain, multilevel models

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study has taken a lifecourse approach, in contrast to previous work which has emphasised particular demographic groups such as the elderly.

Our findings suggest that the relationship between volunteering and mental well-being varies across the life course after adjusting for potential risk factors.

Our study demonstrates that engaging old-aged and middle-aged demographic groups in volunteering activities may be associated with better mental health.

The study was unable to examine selection effects such as whether prior poor health might have restricted people's participation in volunteering particularly at old age.

Introduction

Volunteering means any activity in which time is given freely to benefit another person, group or organisation.1 The present study contributes to the discussion of the health benefits of voluntary action in a British context. At the present time, this analysis is of relevance to a wider policy debate, on subjective well-being. The UK government has begun to invest in efforts to measure subjective well-being, and government policy strongly emphasises the benefits to communities of higher levels of voluntary action. Since mental health is also the subject of public policy, it is reasonable to ask whether voluntary action by individuals can be said to be associated with mental health benefits in a British context.

A recently published meta-analysis2 and other studies indicate a positive relationship between volunteering and health outcomes such as mental well-being, self-rated health, cardiovascular disease (CVD), risk factors for CVD, disability, mental well-being and life satisfaction.1 3–13 Some studies have suggested that engaging in volunteering activities can reduce the risk of mortality,14 15 and others claim that the positive effects of volunteering on health may disappear when volunteering is discontinued.3 8 16

The majority of studies of the relationship between health and volunteering have focused on older individuals, who experience higher levels of illness and depression than the general population. For example, one UK study concluded that volunteering reduced the incidence of depression for those aged over 65 but not for younger age groups.10 In Britain, no previous study has focused on the association of volunteering with mental health by using a wider spectrum of age, including younger and older people. In the absence of studies of the relationship between volunteering and mental well-being over the life course, it could be erroneously assumed that any beneficial effects of volunteering are experienced uniformly across all age groups resulted in misleading assumptions of uniformity of benefiting effects of volunteering on health across the ages. Evidence suggests that participation in volunteering increases with age and may decline at old age.7 As levels of various factors across different ages are not the same, they interact differently at various stages of the life. Therefore, the relationship between mental well-being and volunteering may be more or less evident at different time points across the life course. The lifecourse approach, which involves studying life histories and trajectories, is not novel, but we believe this to be an original study of this kind in a British context.

This study has used the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12 or simply GHQ) as an indicator of mental well-being. The GHQ is a reliable indicator of psychological distress and is a measure of current mental health.17 We have used the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS) in which GHQ is collected at every wave. Recently a study using the BHPS has established lifecourse effects on mental well-being of access to green space, but so far no attempt has been made to exploring such associations in relation to volunteering status.18 We hypothesise that the relationship between volunteering and mental well-being is not linear across the life course, but rather varies at different stages in the life course.

Materials and methods

Data

We used the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS), which is an annual longitudinal survey of private households in Great Britain.19 Longitudinal studies are used to study the dynamics of change across the life course.20 The BHPS started in 1991 as a nationally representative sample of 5000 households, where adults (aged 15 and over) were interviewed and tracked over the years up to 2008. Hence, people of varied ages were surveyed at an initial time point and then followed up over several years. The survey is of high quality and sample attrition rates are low.21 These data were downloaded from the UK Data Archive website (http://www.data-archive.ac.uk). This study is an analysis of previously collected data; therefore, ethical approval was not required.

The BHPS data contain information on various domains of respondents' lives, ranging from income to jobs, household consumption, education and health; it also includes questions about social and political values. Eighteen waves of data were collected before the study was absorbed and extended into the much larger Understanding Society panel data set. Changes in the ways volunteering was measured in Understanding Society mean that we have confined our work to the BHPS data. Information on volunteering was collected in waves 6–18, in alternate years, namely 1996, 1998, 2000, 2002, 2004, 2006 and 2008. We drop data from all waves where the volunteering question was not asked. The data were pooled, yielding 96 735 observations, but we had to discard 30 392 observations (31%) due to incomplete information on the outcome variable, volunteering status and other covariates. The final sample comprised of 66 343 observations (person-years) with no missing data.

No statistically significant differences were found in mean GHQ scores among those observations used in the analysis and the observations for which data were missing. Those missing in analysis data were younger, more likely to be female, more likely to have a low level of education and from manual social class. We also have imputed the missing information using appropriate multivariate imputation techniques and found that results remained essentially unchanged when data generated by multiple imputations were used. Therefore, our analyses are based on 66 343 observations (person-years) with no missing data.

Mental well-being

The outcome of interest was GHQ-12, which is a proxy for mental well-being measured at each wave of the BHPS. It is an index derived from self-completion responses to the GHQ, comprising of 12 questions. Each question has four categories (0–4) that assess happiness, mental distress (such as existence of depression or anguish) and well-being. This subjective assessment is measured on a Likert scale from 0 to 36, that is, the sum of 4 items across 12 questions, which we have recoded so that high values denote high mental disorder. The Likert scoring of the GHQ yielded a normal distribution and we have used this variable as a continuous variable in our analysis. GHQ in the BHPS has been shown to be robust to retest effects, making it a suitable longitudinal instrument. It has also been widely used in health research to measure prevalence and determinants of mental illness and depression.22

Volunteering status

Our main explanatory variable is the frequency of formal voluntary work carried out by individuals. This has been elicited from wave 6 onwards every second year and measured on an ordinal scale as the response to the question: the topic is part of a module of questions introduced by the statement: ‘we are interested in the things people do in their leisure time’. Individuals are asked to respond to a series of options, one of which is whether or not they ‘do unpaid voluntary work’ and if so how frequently they do so. Individuals can respond to this question in five categories, ranging from (1) at least once a week, (2) once a month, (3) several times a year, (4) once a year or less and (5) never. Since the categories once a month and several times a year show very similar trends with time and similar relationships with the GHQ, we merged these categories (2 and 3), generating four categories of volunteering status: frequent (once a week), infrequent (once a month/several times a year), rare (once or less a year) and never. It is known that responses to surveys on volunteering depend on survey methodology. The BHPS asks one question on volunteering and does not prompt respondents with examples of what might be meant by ‘unpaid voluntary work’.23 Therefore, it produces lower estimates of levels of volunteering in Britain than other studies which probe more intensively into the question.24 It is not known whether social or age groups are more or less likely to recall episodes of voluntary work; therefore, we cannot discount the possibility that some groups (eg, those with lower levels of education) might not record volunteering when in fact they have engaged in it.

Other explanatory variables

Potential confounders or pathways linking mental well-being with volunteering were treated as time-varying while gender was treated as a time-constant variable. Age is used as a continuous variable, and to avoid problems of multicollinearity, we use deviations in age from the mean age of the sample, which is around 45 years. The intercept now represents the GHQ score of an individual at the centred value of age 45 years.

Income was based on an adjusted measure of the total gross household income (the McClements scale) to allow for different needs according to household size and composition.25 Income was collected in each wave and we used a logarithmic transformation. Occupational class was measured using the Registrar General's social class system; classes are categorised as manual and non-manual. The highest educational qualification was grouped into three categories: low (education up to O-levels); medium (A-levels or equivalent) and high (university degree including vocational qualification below degree level). Marital status is categorised into: married, unmarried and divorced/separated/widowed. We have also included social group membership which has shown to be protective against depression;26 the responses varied from none (0) to 11, which were further grouped into three categories: 0, 1 and >1 organisations. The measure of health status was represented as self-rated health and categorised as: (1) excellent, (2) good, (3) poor and (4) very poor. The number of children in the household was also included.

Statistical methods

All the analyses were performed on data for men and women combined, as a likelihood ratio test did not indicate differences between them. The normality of the GHQ scores was checked and it was treated as a continuous variable. The relationship between continuous and categorical variables was explored by using analysis of variance, whereas the χ2 test was used between the categorical variables.

Multilevel linear models involving random intercept were used with individuals at level 2 and time or measurements at level 1. The model is of the form:

where β's are the fixed effects, and u and e are the random effects.

Respondents' age was taken as the ‘time’ in our models. We constructed two models; in Model 1, the main effects of age and volunteering status on GHQ scores were adjusted for all the other covariates; and in Model 2, we further introduced a cross-level interaction term between volunteering and age. Finally, the predicted scores of GHQ obtained from the final model were plotted against age, separated by volunteering status and adjusted for all the other covariates. Cubic and quadratic polynomials were used to describe non-linear trajectories, but cubic polynomial was chosen over quadratic because of the better model fit. Finally, the proportions of variances were computed using within and between individuals' variance estimates. All p values presented are two-sided, and the statistical significance level for hypothesis testing was set at 0.05. Analyses were carried out using STATA (V.12.0 for Windows; Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

There were 47% males in our sample. Volunteering status from 1996 to 2008 for the entire sample is displayed in online supplementary figure 1. Almost 80% of people did not undertake any volunteering work during the 12-month reference period, although a variation can be seen by years. For example, in 2002, this percentage dropped to 73% compared to 82% in year 2000, whereas the percentage for those undertaking volunteering once or less a year has increased to 11% in 2002 compared to 3% in 2000. This results from differences in the prompts and showcards offered to respondents in the 2002 wave of the BHPS.24 For this reason, we reanalysed the data by omitting year 2002, but the results were not changed. We therefore retain the data for the year 2002 in this analysis.

bmjopen-2016-011327supp_figures.pdf (158.2KB, pdf)

Table 1 reports the means and percentages of the pooled sample across seven waves. Generally, 21% people volunteered and people who volunteered had better mean GHQ scores (10.7) than those who had not volunteered (11.4). More females than males have volunteered, almost a quarter of those aged 60–74 volunteered compared to 17% in the youngest age group. Those in the youngest age group had the lowest GHQ scores than those in the older age groups. Variations in volunteering status by socioeconomic factors and active member of organisations were found.

Table 1.

Means, SDs or prevalence of variables (n=66 343 person-years; pooled sample across seven waves) from BHPS 1996–2008

| Variables | N (%) | Volunteering |

Mean GHQ (SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequent volunteered | Infrequent volunteered | Rarely volunteered | Never volunteered | |||

| Volunteering | 66 343 | 7% | 9% | 5% | 79% | |

| Mean GHQ score | 66 343 | 10.7 (5.2) | 10.9 (5.2) | 10.8 (5.2) | 11.4 (5.5) | 11.2 (5.4) |

| Mean age (years) | 66 343 | 50.8 (17.0) | 48.2 (15.9) | 40.8 (14.8) | 46.0 (17.7) | 46.3 (17.5) |

| Age groups | ||||||

| 15–29 | 12 653 (19) | 4.3 | 5.8 | 6.8 | 83.1 | 10.6 (5.4) |

| 30–44 | 21 078 (32) | 5.7 | 9.0 | 6.0 | 79.3 | 11.3 (5.5) |

| 45–59 | 16 623 (25) | 7.1 | 10.6 | 5.3 | 77.0 | 11.8 (5.7) |

| 60–74 | 11 002 (17) | 10.7 | 11.3 | 2.9 | 75.0 | 10.9 (5.1) |

| 75+ | 4987 (8) | 7.7 | 6.2 | 1.4 | 84.7 | 11.6 (95.1) |

| Sex | 66 343 | |||||

| Male | 31 014 (47) | 5.6 | 8.7 | 5.3 | 80.5 | 10.5 (5.0) |

| Female | 35 329 (53) | 7.9 | 9.2 | 4.9 | 78.0 | 11.9 (5.7) |

| Marital status | 66 343 | |||||

| Married | 44 709 (67.4) | 6.7 | 9.6 | 5.2 | 78.5 | 11.1 (5.1) |

| Never married | 11 559 (17.4) | 5.8 | 7.3 | 6.6 | 80.2 | 10.8 (5.5) |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 10 075 (15.2) | 8.2 | 7.9 | 3.0 | 80.9 | 12.4 (6.0) |

| Having children in the household | 66 343 | |||||

| Yes | 17 891 (27) | 5.9 | 9.8 | 6.1 | 78.1 | 11.2 (5.4) |

| No | 48 452 (73) | 7.1 | 8.6 | 4.8 | 79.5 | 11.4 (5.5) |

| Level of education | 66 343 | |||||

| Low | 17 552 (26.5) | 5.2 | 4.6 | 2.2 | 88.1 | 11.7 (5.4) |

| Medium | 21 292 (32.1) | 5.9 | 7.5 | 5.3 | 81.3 | 11.2 (5.3) |

| High | 27 499 (41.5) | 8.5 | 12.8 | 6.8 | 71.8 | 11.0 (5.3) |

| Recent social class | 66 343 | |||||

| Non-manual | 38 609 (58.2) | 7.9 | 11.2 | 6.2 | 74.8 | 11.1 (5.4) |

| Manual | 27 734 (41.8) | 5.2 | 5.9 | 3.7 | 85.2 | 11.4 (5.6) |

| Household income* | 66 343 (403.4) | 412.8 | 458.1 | 459.4 | 395.4 | |

| General health | 66 343 | |||||

| Excellent | 15 258 (23) | 7.2 | 9.9 | 6.1 | 76.7 | 9.1 (4.1) |

| Good | 44 817 (68) | 6.7 | 8.9 | 5.1 | 79.2 | 11.2 (5.0) |

| Poor | 6268 (9) | 5.9 | 6.4 | 3.1 | 84.6 | 16.7 (7.4) |

| Active member to organisations | 66 343 | |||||

| None | 35 551 (53.6) | 2.6 | 4.1 | 4.4 | 88.8 | 11.5 (5.6) |

| 1 | 20 226 (30.5) | 8.5 | 10.4 | 5.4 | 75.7 | 11.0 (5.1) |

| 2 or more | 10 566 (15.9) | 17.5 | 22.3 | 7.0 | 53.2 | 10.8 (5.1) |

The associations between categorical variables reported here were significant as indicated by the χ2 test, same is the case of associations between continuous and categorical variables (F-test using ANOVA).

*Monthly income in the McClements Equivalence scale.

ANOVA, analysis of variance; BHPS, British Household Panel Survey; GHQ, General Health Questionnaire; Frequent volunteering, at least once a week; Infrequent volunteering, at least once a month or many times a year; Rare volunteering, once or less a year.

GHQ and volunteering

We plotted the mean GHQ scores and 95% CIs by volunteering status (see online supplementary figure 2). The mean GHQ score was lowest (best) among those who were involved in frequent volunteering and highest (worst) among those who never volunteered.

Results from the random intercept model

After establishing that the association between volunteering and GHQ was not linear, we replaced the five-point volunteering variable with the four categories as discussed earlier in the ‘Materials and methods’ section. In a fully adjusted analysis (table 2; Model 1), all the volunteering categories were significant and had positive GHQ scores for those aged 45 years, indicating that those not volunteering were more likely to experience poorer mental health.

Table 2.

Association between volunteering and GHQ, fully adjusted (n=66 343 person-years), BHPS (1996–2008)

| Variables | Model 1 |

Model 2 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | SE | Coefficient | SE | |

| Constant | 7.127 | 0.374 | 7.092 | 0.379 |

| Age | −0.018 | 0.003* | −0.036 | 0.006* |

| Age2 | −0.002 | 0.0001* | −0.002 | 0.0003* |

| Age3 | 0.00004 | 0.00001* | 0.00004 | 0.00001* |

| Volunteering | ||||

| Frequent | Ref | |||

| Infrequent | 0.270 | 0.096* | 0.288 | 0.129† |

| Rare | 0.313 | 0.111* | 0.333 | 0.149† |

| None | 0.454 | 0.082* | 0.494 | 0.110* |

| Age×volunteering | ||||

| Age×frequent volunteering | Ref | |||

| Age×infrequent volunteering | 0.016 | 0.007† | ||

| Age×rare volunteering | 0.018 | 0.007† | ||

| Age×none volunteering | 0.020 | 0.005* | ||

| Variances | ||||

| Level: person | 9.071 | 0.198 | 9.073 | 0.198 |

| Level: measure | 16.795 | 0.109 | 16.793 | 0.109 |

*Significant at 1%.

†Significant at 5% level.

Model 1: age and volunteering, fully adjusted; Model 2: Model 1+age×volunteering, fully adjusted.

Full adjustment: sex, marital status, number of children, highest qualification, social class, income, general health and active member of organisations; volunteering: frequent, at least once a week; infrequent, at least once a month or several times a year; rare, once or less a year.

BHPS, British Household Panel Survey; GHQ, General Health Questionnaire.

To investigate whether volunteering had a consistent association with GHQ across the life course, interaction terms were fitted between age and volunteering. We also fitted quadratic and cubic interactions of age with volunteering, but they had no significant effects, so were not included in the analyses shown here. Variations in the associations between volunteering and GHQ were seen across the life course indicated by significant interaction terms. To understand these variations, we plotted the predicted GHQ scores obtained from the final model (Model 2). The growth curves (figure 1) suggested three overall periods: an increase to peak in early adult life, decline from midlife up to 75 and then an increase from around 80.

Figure 1.

Trajectories in GHQ scores by volunteering status and age, BHPS (1996–2008). BHPS, British Household Panel Survey; GHQ, General Health Questionnaire.

The GHQ scores were lowest at the youngest ages among those who never volunteered, but then there was a sharp increase in GHQ scores with age, peaking at 11.6 when the participants were 45–50 years old. Likewise, at younger ages, GHQ scores were highest for those who were involved in frequent volunteering during early adulthood to mid-adulthood. Then, GHQ scores started decreasing while for those who never volunteered, and GHQ scores increased. Likewise, those who were involved in either infrequent or rare volunteering also had lower GHQ scores than those who never volunteered.

The proportion of variance within individuals (16.79/16.79+9.07) was 65% in a fully adjusted model indicating heterogeneity in the GHQ by volunteering across the life course. While, between individuals, the proportion of variance was 35% (9.07/9.07+16.79).

Discussion

Principal findings

Previous studies have reported better mental well-being using the GHQ among those involved in volunteering activities. Our study indicates that the relationship between volunteering and mental well-being varies across the life course, which suggests that volunteering may be more strongly associated with mental well-being at some points of the life course than others. There is no clear evidence that volunteering was positively associated with mental health during early adulthood to mid-adulthood. Rather, the positive association began to become apparent after around 40 years and continued up to old age. Those who never volunteered seemed to have lower levels of mental well-being starting around midlife and continuing in old age compared to those involved in volunteering. These associations between mental well-being and volunteering are robust to a range of potential confounders, which are used in adjusting the models.

What is already known on this topic and what this study adds?

Changing roles associated with different age groups across the life course may explain why volunteering is beneficial for some age groups but not for others;7 a comprehensive overview has been provided by Wilson.1 Like previous studies, we also have found that volunteering is not associated with mental well-being during younger ages.1 One explanation might be that during younger ages, volunteering may be perceived of as yet another obligatory task to fulfil in order to be a good student, parent, worker and so forth, so it does not have beneficial effects on health. Contrary to some other studies,7 this study has found potentially beneficial connections between volunteering and mental well-being during the middle stages of the life course. It has been reported previously that middle-age people who are less depressed are more likely to volunteer and thereby enjoy the benefits of being volunteers.27 The benefits of volunteering may also accrue from early middle age because of the social roles and family connections, which are more likely to promote volunteering at that stage of the life course. An example would be that many parents of school-aged children become involved in school-related activities in various voluntary capacities.27 Our results essentially accord with other reports showing that volunteering is positively associated with mental well-being especially during old age,1 5 6 10 13 28–32 but we build on previous literature by adding this lifecourse perspective.

Several mechanisms may explain the positive connection between mental well-being and volunteering. Numerous studies have reported that a person involved in volunteering will have more resources, a larger social network, more power and more prestige, and this in turn leads to better physical and mental health.33 34 It has been found that the positive effect of volunteering on physical and mental health is due to the personal sense of accomplishment that an individual gains from his or her volunteering activities.35 Volunteering may also provide a sense of purpose, particularly for those people who have lost their earnings,7 because regular volunteering helps maintain social networks, which are especially important for older people who are often socially isolated.

We have used three mutually exclusive groups reflecting the degree of participation in volunteering during the year prior to the survey. The GHQ scores were more favourable among those who were involved in volunteering irrespective of its frequency, compared to those who never volunteered. People who were involved in frequent volunteering had much higher GHQ scores up to 40 years than those who were involved in infrequent or rare volunteering, because people may experience role strain and thus will have limited or no physical and mental health benefits of volunteering.9 14 33 34 Our study showed that individuals with even a minimal amount of participation in volunteering activities appeared to have better mental well-being compared to those who were not involved at all. This has also been reported by others.9 14 34 Nevertheless, a high proportion of variance within individuals (65%) also indicate the lifecourse effects of volunteering on mental well-being.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study has several strengths. First, the findings were based on a large-scale national-level longitudinal study in England, which enabled us to explore the associations between volunteering and mental well-being over the life course. Most importantly, our measure of volunteering status has shown robust associations with GHQ scores, for example, we also repeated the results by re-defining the cut-offs of volunteering and not volunteering and the results remained unchanged. Furthermore, the results remained unchanged when data from the 2002 survey were discarded because of changes in the frequency categories of volunteering offered to respondents.

As far as limitations of the work are concerned, the BHPS does not have data on ‘informal volunteering’ (ie, voluntary acts undertaken for the benefit of unrelated individuals, eg, neighbours). Therefore, we were bound in using only ‘formal volunteering’ and were unable to capture a wider spectrum of voluntary activities. Additionally, we were constrained to use GHQ as the measure of mental well-being as this is the only relevant outcome variable in the BHPS (the other, such as WEMWBS, is not collected). Also, in analysing social change there is the possibility, which cannot be ruled out entirely, of cohort effects—that is, if we were able to observe respondents from different birth cohorts at the same ages, we would find significant differences because of the different life experiences of birth cohorts (eg, those who became adults prior to World War II compared to those who grew up under the modern welfare state), but it is not possible to test for such effects over the relatively short run (seven waves of a study, with data gathered between 1996 and 2008) for which these data are available. Finally, we were unable to examine important selection effects, such as whether poor health might have limited whether or not individuals participate in volunteering particularly at old age.

Conclusions and policy implications

The findings from this study are noteworthy: the results are based on a large national-level longitudinal data and the analysis shows that, after adjustment for various potential confounders, the association between volunteering and mental well-being varies at different points in the life course. These findings argue for more efforts to involve middle-aged people to older people in volunteering related activities. Volunteering action might provide those groups with greater opportunities for beneficial activities and social contacts, which in turn may have protective effects on health status. Particularly, with the ageing of the population, it is imperative to develop effective health promotion for this last third of life, so that those living longer are healthier. The results of the study are also relevant to the Marmot Review,36 which emphasises the need for interventions to promote community participation as a way of improving an individual's health and wellbeing. Further research is needed to explore why volunteering at certain points of the life course seems to be better for health than it is at others.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the participants in the BHPS, collected by the ESRC at the University of Essex. The data were made available through the UK Data Archive. The funder played a substantial role in determining the content of the surveys, but played no part in the design, analysis or interpretation of this study; or in drafting this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

Footnotes

Contributors: FT planned this study, conducted the analyses and wrote the manuscript, whereas P S provided the statistical guidance and JM provided conceptual input. Both coauthors commented on the subsequent drafts of the manuscripts.

Funding: This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council, UK (ESRC; grant number: ES/G028877/1), the Office for the Third Sector and the Barrow Cadbury Trust through the Third Sector Research Centre (TSRC).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study is an analysis of previously collected data and therefore ethical approval was not required for this study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Wilson J. Volunteering. Annu Rev Sociol 2000;2:15–240. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jenkinson CE, Dickens AP, Jones K et al. . Is volunteering a public health intervention? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the health and survival of volunteers. BMC Public Health 2013;13:773 10.1186/1471-2458-13-773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Binder M, Freytag A. Volunteering, subjective well-being and public policy. J Econ Psychol 2013;34:97–119. 10.1016/j.joep.2012.11.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burr JA, Tavares J, Mutchler JE. Volunteering and hypertension risk in later life. J Aging Health 2011;23:24–51. 10.1177/0898264310388272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glass TA, De Leon CF, Bassuk SS et al. . Social engagement and depressive symptoms in late life: longitudinal findings. J Aging Health 2006;18:604–28. 10.1177/0898264306291017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenfield EA, Marks NF. Formal volunteering as a protective factor for older adults’ psychological well-being. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2004;59:S258–64. 10.1093/geronb/59.5.S258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y, Ferraro KF. Volunteering in middle and later life: is health a benefit, barrier or both? Soc Forces 2006;85:497–519. 10.1353/sof.2006.0132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meier S, Stutzer A. Is volunteering rewarding in itself? Economica 2008;75:39–59. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morrow-Howell N, Hinterlong J, Rozario PA et al. . Effects of volunteering on the well-being of older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2003;58:S137–45. 10.1093/geronb/58.3.S137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Musick MA, Wilson J. Volunteering and depression: the role of psychological and social resources in different age groups. Soc Sci Med 2003;56:259–69. 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00025-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schreier HM, Schonert-Reichl KA, Chen E. Effect of volunteering on risk factors for cardiovascular disease in adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA Pediatr 2013;167:327–32. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwingel A, Niti NM, Tang C et al. . Continued work employment and volunteerism and mental well-being of older adults: Singapore longitudinal ageing studies. Age Ageing 2009;38:531–7. 10.1093/ageing/afp089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sneed RS, Cohen S. A prospective study of volunteerism and hypertension risk in older adults. Psychol Aging 2013;28:578–86. 10.1037/a0032718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Musick MA, Herzog AR, House JS. Volunteering and mortality among older adults: findings from a national sample. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1999;54:S173–80. 10.1093/geronb/54B.3.S173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okun MA, Yeung EW, Brown S. Volunteering by older adults and risk of mortality: a meta-analysis. Psychol Aging 2013;28:564–77. 10.1037/a0031519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li YP, Chen YM, Chen CH. Volunteer transitions and physical and psychological health among older adults in Taiwan. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2013;68:997–1008. 10.1093/geronb/gbt098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Argyle M. The psychology of happiness. London: Routledge, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Astell-Burt T, Mitchell R, Hartig T. The association between Green space and mental health varies across the lifecourse. A longitudinal study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2014;68:578–83. 10.1136/jech-2013-203767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor M, Brice J, Buck N et al. . British Household Panel Survey User Manual Volume A: Introduction, Technical Report and Appendices. Colchester: University of Essex, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halaby CN. Panel models in sociological research: theory into practice. Annu Rev Sociol 2004;30:507–44. 10.1146/annurev.soc.30.012703.110629 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uhrig SCN. The nature and causes of attrition in the British household panel survey—Institute for Social and Economic Research. University of Essex, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pevalin DJ. Multiple applications of the GHQ-12 in a general population sample: an investigation of long-term retest effects. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2000;35:508–12. 10.1007/s001270050272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rooney P, Steinberg K, Schervish P. Methodology is destiny: the effects of survey prompts on reported levels of giving and volunteering. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q 2004;33:628–54. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Staetsky LD, Mohan J. Individual voluntary participation in the UK: a review of survey information. Working Paper 6; University of Birmingham UK: Third Sector Research Centre, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jenkins S. The British Household Panel Survey and its income data. University of Essex. UK: Institute for Social and Economic Research, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cruwys T, Dingle GA, Haslam C et al. . Social group memberships protect against future depression, alleviate depression symptoms and prevent depression relapse. Soc Sci Med 2013;98:179–86. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rotolo TA. Time to join, a time to quit: the influence of life cycle transitions on voluntary association membership. Soc Forces 2000;78:1133–61. 10.1093/sf/78.3.1133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiao C, Weng LJ, Botticello AL. Social participation reduces depressive symptoms among older adults: an 18-year longitudinal analysis in Taiwan. BMC Public Health 2011;11:292 10.1186/1471-2458-11-292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi KS, Stewart R, Dewey M. Participation in productive activities and depression among older Europeans: Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013;28:1157–65. 10.1002/gps.3936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim J, Pai M. Volunteering and trajectories of depression. J Aging Health 2010;22:84–105. 10.1177/0898264309351310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lum TY, Lightfoot E. The effects of volunteering on the physical and mental health of older people. Res Aging 2005;27:31–55. 10.1177/0164027504271349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piliavin JA, Siegl E. Health benefits of volunteering in the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study. J Health Soc Behav 2007;48:450–64. 10.1177/002214650704800408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moen P, Dempster-McClain D, Williams RM Jr. Successful aging: a life-course perspective on women's multiple roles and health. Am J Sociol 1992;97:1612–38. 10.1086/229941 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Willigen M. Differential benefits of volunteering across the life course. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2000;55:S308–18. 10.1093/geronb/55.5.S308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herzog AR, Franks MM, Markus HR et al. . Activities and well-being in older age: effects of self-concept and educational attainment. Psychol Aging 1998;13:179–85. 10.1037/0882-7974.13.2.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marmot M, Boyce T, McNeish D et al. . Fair soc iety, healthy lives. Strategic review of health inequalities in England post. London, UK: The Marmot Review, 2010. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-011327supp_figures.pdf (158.2KB, pdf)