Abstract

Study Objectives:

Perception of sleep-wake times may differ from objective measures, although the mechanisms remain elusive. Quantifying the misperception phenotype involves two operational challenges: defining objective sleep latency and treating sleep latency and total sleep time as independent factors. We evaluated a novel approach to address these challenges and test the hypothesis that sleep fragmentation underlies misperception.

Methods:

We performed a retrospective analysis on patients with or without obstructive sleep apnea during overnight diagnostic polysomnography in our laboratory (n = 391; n = 252). We compared subjective and objective sleep-wake durations to characterize misperception. We introduce a new metric, sleep during subjective latency (SDSL), which captures latency misperception without defining objective sleep latency and allows correction for latency misperception when assessing total sleep time (TST) misperception.

Results:

The stage content of SDSL is related to latency misperception, but in the opposite manner as our hypothesis: those with > 20 minutes of SDSL had less N1%, more N3%, and lower transition frequency. After adjusting for misperceived sleep during subjective sleep latency, TST misperception was greater in those with longer bouts of REM and N2 stages (OSA patients) as well as N3 (non-OSA patients), which also did not support our hypothesis.

Conclusions:

Despite the advantages of SDSL as a phenotyping tool to overcome operational issues with quantifying misperception, our results argue against the hypothesis that light or fragmented sleep underlies misperception. Further investigation of sleep physiology utilizing alternative methods than that captured by conventional stages may yield additional mechanistic insights into misperception.

Commentary:

A commentary on this article appears in this issue on page 1211.

Citation:

Saline A, Goparaju B, Bianchi MT. Sleep fragmentation does not explain misperception of latency or total sleep time. J Clin Sleep Med 2016;12(9):1245–1255.

Keywords: misperception, insomnia, sleep latency, paradoxical, phenotype

INTRODUCTION

Assessment of sleep often includes subjective reports of sleep-wake durations, in clinical practice as well as epidemiological studies of sleep duration.1 However, when concurrent objective sleep measurements are available, it is not uncommon to observe that the subjective responses may differ. Underestimation of total sleep time has been previously observed in healthy adults under experimental circumstances, as well as insomnia patients during polysomnography (PSG).2–4 This phenomenon, sometimes termed misperception, may manifest as either overestimating sleep latency (SL) or underestimating total sleep time (TST), or both.4 Some patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) may also exhibit misperception, though perhaps not to the same extent as those with insomnia symptoms.5–7

Several hypotheses have arisen regarding the basis for misperception, although a unified explanation remains elusive. For example, misperception has been linked with anxiety and mood,3,8 personality traits, and sleep physiology measures such as electroencephalogram patterns of alpha-delta sleep or cyclic alternating pattern and high frequency electroencephalography (EEG) content.9–13 In addition, we previously investigated possible relations between sleep architecture and misperception of TST as a means to test the hypothesis that sleep fragmentation is associated with misperception. Using metrics such as stage time and percentage, sleep efficiency, arousal index, and amount of stage N1, we found no reliable predictors for the degree of TST misperception in patients with or without OSA.6,7 The difficulty in linking sleep metrics to misperception could be due to insensitivity of the metrics for capturing the relevant physiology and/or the manner in which misperception is quantified. For example, survival analysis and similar approaches focusing on sleep stage transition dynamics have been shown to capture fragmentation related to OSA more effectively than standard metrics.14–16

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Sleep misperception is not uncommon, particularly in patients with insomnia. However, the mechanistic basis remains uncertain, in part because of challenges in quantifying the perception phenotype.

Study Impact: We introduce a novel phenotyping approach that facilitates hypothesis-testing in populations with misperception. Combined with stage-transition analytics, we found no evidence to support the common hypothesis that sleep fragmentation underlies misperception.

Although the basis for sleep misperception remains uncertain, understanding this phenomenon is important for epidemiological assessments of sleep duration as well as clinical assessment of patient with insomnia. Recent data emphasizes the importance of perception, as the first group to perform objective PSG testing in a large longitudinal cohort clearly demonstrated that health risks such as hypertension, diabetes, and mortality, previously attributed to insomnia symptoms or self-reported short sleep durations, may in fact be mainly attributed to the subset of patients with the combination of insomnia symptoms and objective short TST on PSG.17 Therefore, risk-benefit considerations in regards to hypnotic medications may be informed by the degree of misperception, especially in light of the growing literature regarding the adverse effects associated with hypnotic medications, including falls, motor vehicle accidents, and parasomnia.18,19 Of note, there is no evidence that extending sleep duration or continuity via hypnotic therapy mitigates the risks thought to be associated with insomnia. Importantly, misperception may itself be a target for intervention, as several publications suggest that misperception is state-like. For example, misperception can be induced in healthy adults,2 can be improved in those with comorbid sleep apnea and insomnia during continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) titration6 and can be improved in insomnia patients using actigraphy-based feedback.20 Distinguishing misperception from objective reduced sleep duration among insomnia patients has implications for treatment by identifying subsets who may be more amenable to non-pharmacological methods.17

We undertook the current study to reassess measures of sleep fragmentation to test the hypothesis that light or fragmented sleep underlies misperception observed in the sleep laboratory setting. In addition, we implemented the novel metric of sleep latency misperception that addresses two phenotyping challenges that tend to overestimate misperception: the need to define objective SL, which has no gold standard, and the assumption that latency misperception and TST misperception are independent processes.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective analysis on n = 643 adult patients who underwent diagnostic PSG in our clinical sleep laboratory. The institutional review board approved the retrospective analysis of this database without requiring consent. This cohort included 2 clinical groups: patients with mainly mild or moderate obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and patients without OSA (defined by an apnea-hypopnea (4%) index (AHI) of < 5, and a respiratory disturbance index (RDI) of < 15). These populations exhibit a range of misperception and insomnia symptoms, as reported previously.6,7 Each patient completed a post-sleep survey after overnight testing in our clinical laboratory, in which they indicated their subjective recollection of sleep latency and total sleep time. Responses in units of hours and minutes were compared with objective sleep stage scoring performed by experienced technicians according to American Academy of Sleep Medicine guidelines.

The most common reason for PSG in our center is to evaluate for OSA. However, our system does not allow reliable verification of indication, as referrals come from diverse practices beyond the sleep clinical division. Self-reported insomnia symptoms were quite common in our pre-sleep questionnaires. Although we do not have detailed information regarding the diagnosis or insomnia sub-phenotypes, over 70% of subjects reported at least 1 insomnia symptom (defined by either listing insomnia as the reason for study, or endorsing difficulty with sleep onset or maintenance). In addition, self-reported psycho-tropic medications were common. Over half of the cohort listed at least one agent from classes including antidepressant, anxiolytic, or hypnotic prescriptions, with the majority being the antidepressant class. We do not have reliable data as to which sleeping medications were taken on the night of study itself.

SDSL and Latency Adjustment

For each patient, the full night of PSG recording was divided into time before versus after the subjective sleep latency demarcation (relative to lights-out time). We defined the objective scored sleep occurring between lights out and the subjective SL value as the “sleep during subjective latency” (SDSL). The SDSL value is > 0 minutes if any SL misperception occurred; if subjective SL is exactly accurate or underestimated, then the SDSL value will be zero. A small portion of patients underestimated their sleep latency, by reporting less time to fall asleep than the objective onset. Specifically, less than 10% showed latency underestimation of any duration, with less than 5% showing more than 5 minutes of latency underestimation. This was similar in both the OSA and the no-OSA cohorts. In the analysis of sleep stages occurring during SDSL, we prespecified groups of 5–20 min of sleep (as the “control” group), and > 20 min of sleep (representing the top half approximately of misperception captured by SDSL). We focused on those who perceived wake despite sleep occurring as the most clinically relevant form of misperception, in the context of insomnia. Perception of sleep during periods of objective wake (another form of misperception) was not considered, and would not be relevant for insomnia, but could be theoretically relevant for epidemiology (with respect to long-duration self-reports being associated with adverse health outcomes.1

The objective sleep duration after the demarcation of subjective latency is termed the “latency adjusted total sleep time” (LA-TST). This correction leads to a reduction of the objective TST value for patients who overestimated their SL. The correction is based on the assumption that each patient's subjective SL estimate becomes a temporal anchor for their TST estimate. In other words, when patients reflect back on their night in the lab to answer the post-PSG survey questions, they first consider their SL, and then consider their TST as time between the subjective SL and final wake-up time. The reverse possibility seems less likely, which would be that patients estimate their SL by starting from the morning wake time, subtracting their estimates of TST and wakefulness during the night, and then using the remaining time between lights out and this constellation of times to infer their SL value. Although it remains unknown exactly what heuristics patients use to estimate their sleep, utilizing the SDSL metric overcomes operational problems with defining objective SL (for which there is no gold standard), and avoids double counting the degree of misperception in those who have both SL and TST misperception which inevitably occurs when they are considered independent from each other.

While we recognize that the degree of misperception is a continuous variable, we prespecified 2 misperception groups on which to focus our analysis based on the difference between the subjective TST and the objective LA-TST. The prespecified cutoff value for misperception was ≥ 60 min underestimation of the LA-TST value, while those with a subjective TST estimate within 30 min of the LA-TST value (over- or underestimation) were considered the comparator (“control”) group.

Cumulative Distribution Function Plots

We utilized a transition probability approach to quantify sleep fragmentation. For each patient (one night), we calculated the cumulative distribution function (CDF) for each sleep stage. In a CDF plot, the Y-axis reflects the portion of bouts of a given stage that are less than or equal to the duration value on the X-axis. In that sense, CDFs are conceptually similar to survival curves. We created 95% confidence intervals for the average CDF for each stage by averaging the CDFs across all patients in each group. Some patients had no REM or N3 stages during their PSG (2% to 7% and 1% to 3% in OSA and non-OSA groups, respectively); in these cases, instead of omitting these individuals, we included them by treating the CDF as having a value of 1 in the first X-axis value (that is, they could contribute as if the bout durations were more brief than a single epoch; omission would tend to make the CDF curve more shallow).

Statistics

We used custom code in MATLAB software (The Mathworks, Inc., Natick, MA) to extract sleep stage bouts and transitions from exported scoring files obtained from clinical PSGs. We evaluated the area under the curve for the CDFs to compare groups (each subject contributes one AUC value for each stage, which was calculated in a uniform prespecified time window from 0 min to 40 min on the X-axis). We used Prism (Graph-Pad software, Inc., La Jolla, CA) to perform statistical analysis. The nonparametric Mann-Whitney Test was performed for group comparisons when data were distributed non-normally.

RESULTS

We first investigated the phenomenon of SL misperception, to test the hypothesis that light or fragmented sleep occurring early in the night would be perceived as wakefulness. Defining SL misperception involves two potential confounds: (1) deciding which definition of objective SL to use, and (2) deciding whether to quantify the difference between subjective and objective SL in absolute (minutes) versus relative (percentage) terms. These issues are important because there is no gold standard for defining objective SL, and different definitions will yield different results and could impact interpretation.7 For example, Figure 1A illustrates the range of results obtained if we define objective SL by either the first epoch of sleep versus the latency to persistent sleep (LPS; 10 epochs). We reasoned that the fundamental goal of describing SL misperception is to capture the amount (and type) of sleep that is misperceived during the period of subjective sleep latency, which is not accurately captured by the routine method of subtracting subjective onset and objective onset (regardless of how objective onset is defined). To illustrate this, Figure 1B shows a cartoon of 2 hypothetical individuals who each have a 2-hour subjective SL estimate, but with different objective SL. Using a standard method of subtracting subjective and objective latency resulted in markedly different values for SL misperception: 120 min of error versus 20 min of error. However, each patient fundamentally misperceived the same amount of sleep during the subjective SL experience: 20 minutes. In contrast to the standard methods, which require arbitrary definitions of sleep onset, using the SDSL method captures the degree of misperception associated with the subjective SL experience: how much sleep occurred during the experience of sleep latency. It is naturally expressed in absolute time units, and must be equal or greater than zero. A small portion of patients estimated their latency earlier than objective measures (∼10% with any underestimation, ∼5% with more than 5 min), which would be considered to have SDSL values of zero. SDSL can thus be analyzed to test the hypothesis that light or fragmented sleep during the onset period is perceived as wake. We investigated 2 cohorts, defined by the presence or absence of OSA. The characteristics of the 2 cohorts are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1. Subjective and objective sleep latency measures.

(A) The relationship between objective sleep latency (SL) and objective latency to persistent sleep (LPS) for the OSA group (n = 391). The dashed identity line indicates when the two are equal. The values below that line indicate individuals for whom the objective latency is less than the LPS. (B) Schematic illustrating two scenarios with equal sleep during subjective latency (SDSL) but different misperception measured in the typical manner of defining objective latency (sleep, gray shading; wake, white). In each case, the subjective SL estimate is two hours and the sleep occurring within that estimate (i.e., the SDSL) is 20 min. In the top example, the objective latency is 20 min, while the bottom example has an objective latency of 100 min. In the top example there is an error of 120 min, while in the bottom example there is an error of 20 min. (C) The relationship between SDSL and misperception of latency, as defined by the subjective minus objective latency (S-O SL) for OSA subjects (C; n = 391) and non-OSA patients (D; n = 252).

Table 1.

Population characteristics.

The SDSL measure of misperception differed from misperception values obtained by standard calculations based on objectively defined SL in both OSA patients and non-OSA patients (Figure 1C and 1D). The differences arise depending on the pattern of sleep that occurred during subjective latency. For example, if sleep is continuous (no awakenings) after objective sleep latency, then SDSL will be identical to the SL misperception value calculated by standard subtraction methods. When subjective SL is overestimated, the SDSL could be equal to or less than the calculated SL misperception.

It is now possible to test the hypothesis that SDSL, as a measure of latency misperception, is related to lighter sleep stage content and increased transitions. We first investigated whether latency misperception as defined by SDSL was related to the stage transition rate as a surrogate for fragmented sleep. We defined sleep transitions when a bout of any stage was terminated by transition to another sleep sub-stage or to wake. We prespecified 2 groups of SL misperception defined by the threshold SDSL value of 20 min, which was near the medians of the 2 cohorts (19.5 in the OSA group, and 15.5 in the non-OSA group). In other words, we are comparing two subgroups with more or less amount of sleep occurring during their subjective experience of onset latency (i.e., their SDSL). The group with 5–20 min of SDSL served thus as a comparator group, versus those with > 20 min of SDSL representing those with more prominent latency misperception. If misperception during sleep onset latency is related to light or fragmented sleep, we would expect to find those with greater SDSL to have more transitions and N1% and less REM% and N3%. Contrary to our hypothesis that lighter or more fragmented sleep would be more likely to be misperceived, we observed similarly in those with or without OSA that misperception (indicated by higher SDSL values) was associated with less N1%, more N3%, and lower transition frequency in both groups; additionally, in the non-OSA group, misperception was also associated with greater REM% (Figure 2). In other words, patients with more sleep occurring during the subjective experience of sleep onset latency had more stable sleep, with less N1% and more of REM% and/or N3%.

Figure 2. Sleep architecture during subjective sleep latency.

Analysis of sleep stages for OSA patients (A) and non-OSA patients (B) divided according to SDSL values: 5–20 minutes SDSL (white) and with > 20 SDSL (gray). Data is presented as box and whiskers plots, with the median, 25% and 75% box boundaries, and whiskers indicating the 5–95% range, and dots for those outside the whisker range. The left Y-axis refers to the percentage time spent in each sleep stage. The right Y-axis refers the transition frequency (per minute of objective sleep time as SDS) of any stage, and refers only to the right-most two columns.

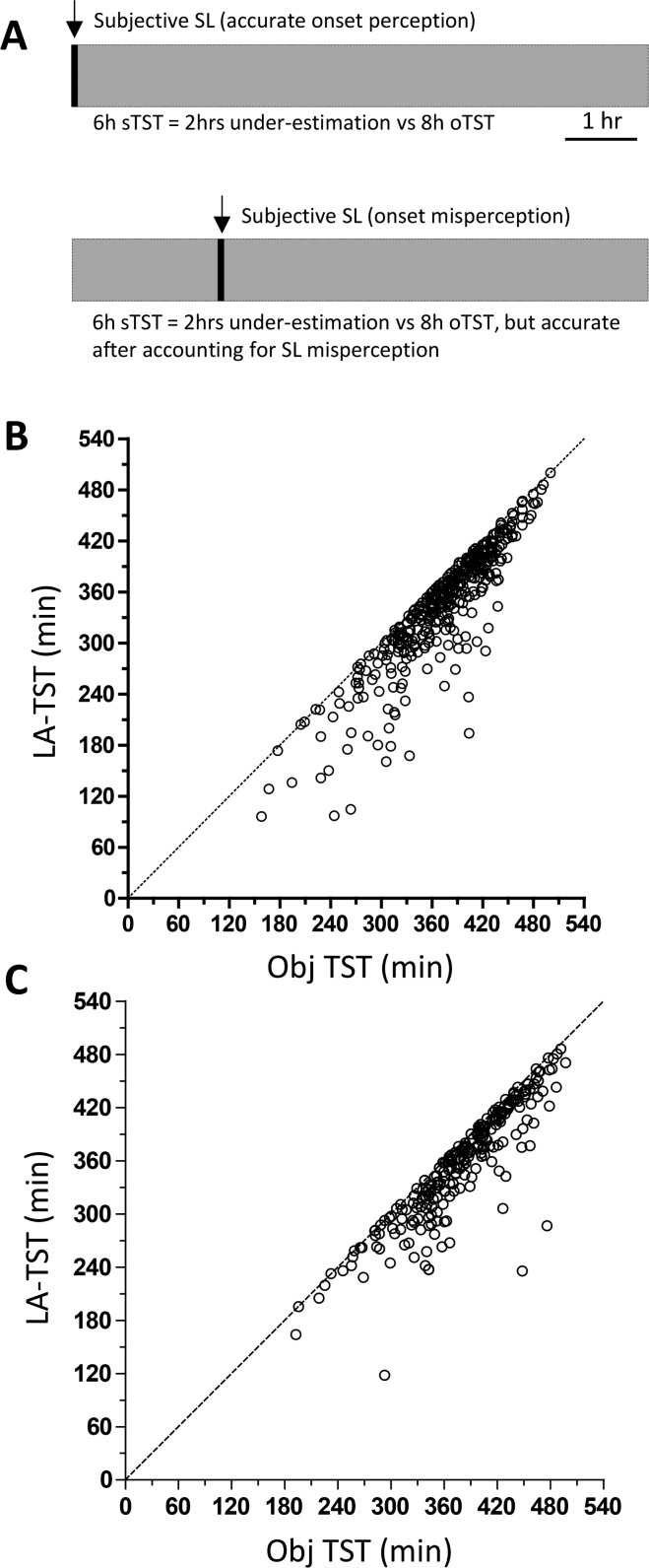

Assessing sleep-wake patterns in patients with insomnia typically includes two main questions: how long did it take to fall asleep and how much total sleep occurred. The latter question, though apparently straightforward, may be influenced by the perceptual SL experience. Although TST and SL misperception are commonly analyzed as independent experiences, doing so may result in “double counting” misperception for individuals who overestimated their SL and underestimated their TST. Figure 3A is a cartoon illustration of 2 hypothetical individuals with the same objective TST of 8 h and subjective TST of 6 h, but with different SL misperception values. In the first case, the subjective SL was accurate and thus, the misperception phenotype was limited to the subjective TST (2-h underestimation of TST). In the second case, the SL was overestimated by 2 h and thus, both subjective SL and subjective TST will be classified as showing misperception if they are considered as independent experiences. However, if recollection of sleep-wake times begins with SL estimate, which then “anchors” the subsequent TST estimate, a different interpretation of the data arises. This alternative interpretation would be that only SL was misperceived, while their TST estimate of six hours would be considered accurate in the sense that it was internally consistent after accounting for the degree of SL misperception (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Adjusting total sleep time for sleep during subjective latency (SDSL).

(A) Schematic illustrating two scenarios of patients each with 8 h of objective TST and 0 min latency, but distinct misperception phenotypes. In each case, the subjective TST is 6 h, but in the top example the subjective SL is accurate (0 min), while in the bottom example SL is overestimated by 2 h. In the top example, standard methods of subjective minus objective TST yields a TST misperception of 2 h (and no correction for SDSL is needed because subjective latency was accurate). In the bottom example, standard methods would also yield a TST misperception of 2 h; however, after, correcting for the SDSL, there would be zero min of TST misperception. (B) The relationship between objective TST before (X-axis) versus after (Y-axis) the correction for SDSL for OSA patients. The dotted identity line indicates no SL overestimation (i.e., SDSL is zero, and there is no adjustment to objective TST). Values below that line indicate the extent to which latency was overestimated subjectively. (C) Same analysis as panel B, for non-OSA patients.

Therefore, we analyzed TST misperception in the 2 cohorts (with versus without OSA) after adjusting each individual for their degree of SL misperception. We term this within-individual correction the “latency-adjusted TST” (LA-TST). Figure 3B and 3C illustrate the effect of this correction by plotting the adjusted TST versus the objective TST over the entire night for each patient, in the OSA and non-OSA groups, respectively. If SL estimates were accurate (no SL misperception), all of the plotted points would fall on the diagonal; however, if SL were overestimated, the LA- TST values would fall below the diagonal. This plot demonstrates that a substantial amount of double-counting may be occurring if TST misperception is considered independently of SL misperception.

Next, we tested the hypothesis that misperception based on the LA-TST was driven by light or fragmented sleep as determined by sleep stage percentage (Figure 4). To accomplish this comparison, we pre-specified subgroups defined by the quantity of LA-TST misperception: ≥ 60 min being the misperception subgroup, and within 30 min as the “control” subgroup. We observed no significant differences in stage percentage between these subgroups, with similar results for the OSA and non-OSA cohorts (Figure 4A and 4B, respectively). In addition, there was no correlation between the AHI and the LATST misperception in the OSA cohort (R < 0.01)

Figure 4. Sleep stages percentages do not predict misperception of latency adjusted total sleep time.

(A) OSA patients with > 60 min of LA-TST misperception (MP; gray bars, n = 92) do not differ in stage percentage compared to those who were accurate within 30 min (white bars, n = 141). Data is presented as box and whiskers plots, with the median, 25% and 75% box boundaries, and whiskers indicating the 5–95% range, and dots for those outside the whisker range. (B) Same analysis as in Panel A, for non-OSA patients with > 60 min of LA-TST misperception (MP; gray bars, n = 76) compared to those who were accurate within 30 minutes (white bars; n = 114).

Despite the negative result above, the hypothesis that fragmentation drives misperception of sleep duration required further investigation. We note that characterizing sleep architecture through stage percentage is an insensitive method for capturing sleep fragmentation.16,21 Therefore, we also investigated bout duration for each sleep stage across these groups. This approach allowed us to assess whether more sensitive measures could support the hypothesis that fragmentation drives misperception. We thus analyzed the bout distributions via cumulative distribution function (CDF) to determine if increased transitions (i.e., increased fragmentation) were evident in the group with ≥ 60 min of LA-TST misperception. CDF plots were obtained for each sleep stage, in each group defined by the misperception sub-groups as above, for the OSA (Figure 5A–5D) and the non-OSA (Figure 5E–5H) cohorts. Sleep fragmentation associated with increased transitions (and thus, shorter bout durations) will manifest in the CDF as a steeper rise of the curve with the inflection approaching the upper left region of the plot. In contrast to our hypothesis that misperception is associated with fragmentation, we observed that the CDF curves had more shallow slopes in the misperception group, indicating that longer rather than shorter bouts occurred. To quantify this trend, we calculated the area under the curve (AUC) for each stage. The AUC analysis showed significantly lower values (indicating longer bout durations) for the misperception group for stages N2 and REM sleep for the OSA group (Figure 5I), and lower values for N2, N3, and REM in the non-OSA group (Figure 5J). In other words, this finding was the opposite direction as would be expected based on our hypothesis that misperception would be greater with increased sleep fragmentation.

Figure 5. Cumulative density function plots of sleep stage bout durations in those with versus without LA-TST misperception.

OSA patients with > 60 min of LA-TST misperception (MP; red line, n = 92) are plotted with lower 95% confidence interval (dashed red line), compared with those who were accurate within 30 min (black line, n = 141), and upper 95% confidence interval (dashed solid line). The panels correspond to each sleep stage: N1 (A); N2 (B); N3 (C); REM (D). Similar analysis is shown for non-OSA patients with > 60 min LA-TST misperception (n = 76) and those who were within 30 min (n = 114), for each sleep stage: N1 (E); N2 (F); N3 (G); REM (H). (I, J) The area under the curve (AUC) of the CDFs are compared according to the misperception groups above (open bars, within 30 min of LA-TST; gray bars, > 60 min LA-TST misperception), for OSA patients (I) and non-OSA patients (J). Brackets indicate significant differences (Mann-Whitney U test, p < 0.05).

Figure 6 illustrates how redefining the misperception phenotype using the concepts of SDSL and LA-TST alters phenotypic categorizations. We considered the cohorts (OSA and non-OSA) first according to typical metrics (i.e., not using the Latency-Adjustment), and how adjustment would impact categorization. We observed that 72 of the 391 OSA patients and 44 of the 252 non-OSA patients would be re-categorized in some fashion (Figure 6). Most of the re-classifications were from the “both” category to latency only, and from latency only to “neither.” In other words, those initially categorized as having both types of misperception were re-distributed into just TST misperception, just SL misperception, or neither of the categories. Some were re-categorized as normal by SDSL because they had < 20 min of SDSL but a block of 10 min of sleep meeting LPS criteria that started > 20 min before their subjective SL (resulting in > 20 min apparent SL misperception).

Figure 6. Misperception phenotype categories using standard versus SDSL-based methods.

(A) The presence or absence of latency and total sleep time misperception are given as “present” or “absent,” respectively, for OSA patients (n = 391). The resulting 4 boxes capture the 4 possible combinations of these binary categories. The arrows indicate the number of patients in the categories defined by standard methods that would be re-categorized after implementation of SDSL analysis for defining latency misperception and LA-TST misperception. For example, the arrow between “Both” and “Latency” indicates that implementing SDSL caused 47 individuals considered by traditional metrics to have both forms of misperception exhibit only latency misperception as a result of SDSL correction. All re-categorizations are to lesser forms of misperception. (B) The same analysis as in panel A, applied to non-OSA patients.

DISCUSSION

This study tested the hypothesis that light or fragmented sleep drives the phenomenon of sleep-wake misperception by applying standard and novel analytics to clinical PSGs in cohorts with or without OSA. Specifically, we introduced the metric of sleep during subjective latency (SDSL), as an opportunity to revisit the physiological underpinnings of misperception. We show that SDSL confers three potential advantages over standard SL misperception metrics. First, it avoids the need to define objective SL, for which there is no gold standard.22 Second, reporting SDSL in units of minutes avoids the potentially divergent results when standard SL misperception metrics are reported in absolute versus relative terms.7 Third, it facilitates “correction” of the objective TST, what we termed the LA-TST, and thus avoids double-penalizing TST estimations in individuals who also exhibited SL misperception. Our results do not support the hypothesis that light or fragmented sleep drives misperception of sleep onset or of total sleep. In fact, the opposite pattern was observed: misperception was associated with lower N1% and transition rate (for SDSL), and less fragmentation by bout duration analysis (for TST).

Sleep Latency: Physiology and Perception

Sleep latency assessment may utilize subjective or objective methods, depending on the clinical context (for example, insomnia diaries versus multiple sleep latency testing for narcolepsy, respectively). Quantifying sleep latency may involve visual classification such as clinical scoring, or can involve behavioral metrics such as active response paradigms or passive motor tone measurements.22 We recently reported a hybrid approach in which subjects were instructed to gently squeeze a ball held in the hand in time with the breathing cycle until sleep latency.23 Whether a behavioral or EEG-based standard is used, the point of onset requires choosing some operational definition, and consequently, lacks a gold standard. Thus, any definition of objective SL may introduce variance into quantifying SL misperception by usual methods of subtracting subjective and objective sleep onset. Despite these operational issues, prior work suggested that SL misperception was linked to increased EEG beta frequency power at or near sleep latency.24,25 Similarly, a study of memory consolidation suggested that auditory stimuli recollection was increased in those with elevated beta activity in the first 10 minutes of sleep, suggesting conscious processing in some individuals may be linked to EEG frequencies.26 In addition, Nofzinger et al. reported increased brain metabolism on functional imaging (during wake and sleep) of insomnia patients, although misperception was not explicitly measured.27

Perception of Total Sleep Time

Self-reported total sleep duration is a driving factor in routine clinical sleep assessments, especially for patients with insomnia. In the context of clinical research, most epidemiological studies rely on self-reported sleep duration, the response to which depends on the clinical history (insomnia, depression), demographics, and socioeconomic status.1,4,28 Sleep-wake duration reports also depend on when29 and how30 the question is asked. Misperception may contribute to some portion of short sleep duration responses, which are often emphasized in epidemiological studies as being associated with adverse health consequences. Recent epidemiology work using PSG at enrollment emphasizes that making this distinction is not merely an academic curiosity, as incident medical and psychiatric disorders were significant only in the subset with both insomnia symptoms and objective short sleep duration.17,31

The physiological basis of TST misperception still remains elusive. Abnormal time perception is not felt to be a major component.29,32 Psychological factors such as personality characteristics and mood disorders have been linked to misperception.9,33,34 Aspects of sleep physiology have been associated with misperception, including hyperarousal,35 alpha frequency intrusion into slow wave sleep,11 and the cyclic alternating pattern12 (but this has not been seen in other work).36 In addition, in regards to the hyperarousal theory of insomnia,35 insomnia patients have increased basal metabolic rate and longer sleep latencies during nap studies, among other physiological changes. The constellation of prior work demonstrates the difficulty so far in understanding the physiological cause of TST misperception. It is possible that some of the heterogeneity in the prior literature is related to imprecise phenotyping and double-counting in those individuals with both onset and total sleep misperception. Revisiting these questions utilizing the SDSL method could unmask stronger relationships in future studies.

Quantifying Sleep Architecture Fragmentation

The method of sleep assessment is another important factor to consider in studies aiming to link architecture patterns to clinical phenotypes. For example, prior work in characterizing sleep architecture in sleep apnea patients indicates that stage percentages are an insensitive measure of sleep fragmentation, whereas sleep bout duration analytics showed better sensitivity.14–16 We previously investigated PSG features such as sleep stage percentage or sleep efficiency as possible correlations between misperception of TST and architecture of sleep; however, none of these served as predictors.7 In this study, we tested the hypothesis that TST misperception was related to sleep fragmentation via analysis of CDF plots. The AUC of these nonparametric (mode-independent) plots capture the degree of fragmentation: more transitions result in shorter bout durations and thus increased AUC values. The results argued against our hypothesis and in fact, the CDF plots suggested longer REM and N2 bout durations (i.e., more stable sleep) in those with > 60 minutes of misperception. Future work should assess other aspects of sleep physiology (such as EEG) that may contribute to misperception. For example, spindle and alpha activities have been linked to resistance to sensory perturbation,37–39 which may impact perception. REM sleep has been reported as contributing to the subjective sense of wakefulness in sleep, which could be consistent with our observation that more stable REM was linked to TST misperception.40 Having an operational definition of misperception, through the use of SDSL, offers an important opportunity to revisit physiological studies that might have encountered heterogeneity attributable to the standard method of considering latency and total time misperception separately.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations that could be explored in future studies. First, we assessed sleep on a single night of PSG in the laboratory setting. This retrospective methodology precludes assessing whether misperception occurs similarly in the home setting, or whether perception may vary from night to night (e.g., first night effect). Sleep perception is malleable and thus state-like in at least some circumstances,2,6,20 although trait-like perception is possible and can be explored with repeated measures approaches. Second, the population is heterogeneous regarding comorbidities, which might impact morning survey responses. Third, we did not investigate the personality, mood, or cognitive processes that patients may employ when asked to estimate their total sleep, onset latency, and wake time, which may exhibit heterogeneity among patients. Fourth, our comparator groups were selected based on perception, rather than recruiting a cohort of healthy adults to serve as control subjects. Fifth, we did not investigate other aspects of physiology that might predict misperception, such as EEG or autonomic measures. Fifth, the population was heterogeneous in terms of insomnia symptoms; future studies should focus on carefully characterized insomnia patients to determine the external validity of our observations. Finally, medications could affect the perception of sleep. Predicting the impact of medication is challenging, as there may be direct and indirect effects on sleep physiology (introducing heterogeneity into our sleep stage assessments) or memory consolidation processes (introducing variance into the outcome measure of perception).41,42 For example, many antidepressants and other psychotropics suppress REM sleep, which may affect memory processes, including consolidation,41 and may increase motor restlessness, which has been linked to impaired cognitive function.43 If altered memory formation underlies misperception, then memory of sleep would be selectively impaired (or memory for wake selectively preserved). Sedating medications may alter arousal thresholds and/or exacerbate sleep disordered breathing,44 each of which might impact the perception of sleep-wake state. Conversely, certain psychotropic medications may be addressing sleep or mood disorders that themselves could impact sleep, perception of sleep, or memory formation. Each of these possible contributors could in theory be investigated in future prospective investigations.

Clinical Implications

In addition to fundamental scientific questions of how conscious perception can vary during EEG-defined sleep stages, clinical practice is directly impacted by sleep duration perception. Since cardiovascular, metabolic, and psychiatric risks are seen only in those insomnia patients with objective short sleep time,17,31 understanding where a given patient's diary reports fall on the spectrum of misperception could help inform treatment discussions. For example, risk-benefit considerations regarding hypnotic medication use are often made without understanding the extent of misperception (because most insomnia patients are not undergoing PSG in general practice). Weighing the risks of medications is crucial, especially if it extends beyond the short term in those with chronic or refractory insomnia, as a variety of adverse events have been reported including falls, motor vehicle accidents, parasomnia, and even mortality.18,45 Those without objective short sleep duration may carry less medical and psychiatric risk than previously thought, and may respond to non-pharmacological interventions.17 Therefore, clinical assessment of misperception is not about “right or wrong,” but rather it offers potentially actionable information. Additionally, we speculate that clinicians (or patients) might reason that misperception is a “marker” of light or fragmented sleep, to reinforce their assessment of severity of phenotype, when in fact the opposite conclusion may be warranted.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. Dr. Bianchi receives funding from the Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, the Center for Integration of Medicine and Innovative Technology, and the Milton Family Foundation. Dr. Bianchi has a patent pending on a home sleep monitoring device. Dr. Bianchi received travel funding from Servier, has consulting agreements with Foramis, MC10, Insomnisolv, International Flavors and Fragrances, and GrandRounds, and has provided expert testimony in sleep medicine. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AHI

apnea-hypopnea index

- AUC

area under the curve

- CDF

cumulative distribution function

- CPAP

continuous positive airway pressure

- EEG

electroencephalography

- LA-TST

latency adjusted total sleep time

- NREM

non-rapid eye movement

- OSA

obstructive sleep apnea

- PSG

polysomnography

- RDI

respiratory disturbance index

- REM

rapid eye movement

- SDSL

sleep during subjective latency

- SL

sleep latency

- TST

total sleep time

REFERENCES

- 1.Kurina LM, McClintock MK, Chen JH, Waite LJ, Thisted RA, Lauderdale DS. Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: a critical review of measurement and associations. Ann Epidemiol. 2013;23:361–70. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bianchi MT, Wang W, Klerman EB. Sleep misperception in healthy adults: implications for insomnia diagnosis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:547–54. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edinger JD, Fins AI. The distribution and clinical significance of sleep time misperceptions among insomniacs. Sleep. 1995;18:232–9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.4.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harvey AG, Tang NK. (Mis)perception of sleep in insomnia: a puzzle and a resolution. Psychol Bull. 2012;138:77–101. doi: 10.1037/a0025730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCall WV, Turpin E, Reboussin D, Edinger JD, Haponik EF. Subjective estimates of sleep differ from polysomnographic measurements in obstructive sleep apnea patients. Sleep. 1995;18:646–50. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.8.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castillo J, Goparaju B, Bianchi MT. Sleep-wake misperception in sleep apnea patients undergoing diagnostic versus titration polysomnography. J Psychosom Res. 2014;76:361–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bianchi MT, Williams KL, McKinney S, Ellenbogen JM. The subjective-objective mismatch in sleep perception among those with insomnia and sleep apnea. J Sleep Res. 2013;22:557–68. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carskadon MA, Dement WC, Mitler MM, Guilleminault C, Zarcone VP, Spiegel R. Self-reports versus sleep laboratory findings in 122 drug-free subjects with complaints of chronic insomnia. Am J Psychiatry. 1976;133:1382–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.133.12.1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vanable PA, Aikens JE, Tadimeti L, Caruana-Montaldo B, Mendelson WB. Sleep latency and duration estimates among sleep disorder patients: variability as a function of sleep disorder diagnosis, sleep history, and psychological characteristics. Sleep. 2000;23:71–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edinger JD, Krystal AD. Subtyping primary insomnia: is sleep state misperception a distinct clinical entity? Sleep Med Rev. 2003;7:203–14. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2002.0253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinez D, Breitenbach TC, Lenz Mdo C. Light sleep and sleep time misperception - relationship to alpha-delta sleep. Clin Neurophysiol. 2010;121:704–11. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parrino L, Milioli G, De Paolis F, Grassi A, Terzano MG. Paradoxical insomnia: the role of CAP and arousals in sleep misperception. Sleep Med. 2009;10:1139–45. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonnet MH, Arand DL. Physiological activation in patients with sleep state misperception. Psychosom Med. 1997;59:533–40. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199709000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norman RG, Scott MA, Ayappa I, Walsleben JA, Rapoport DM. Sleep continuity measured by survival curve analysis. Sleep. 2006;29:1625–31. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.12.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swihart BJ, Caffo B, Bandeen-Roche K, Punjabi NM. Characterizing sleep structure using the hypnogram. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4:349–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bianchi MT, Cash SS, Mietus J, Peng CK, Thomas R. Obstructive sleep apnea alters sleep stage transition dynamics. PloS One. 2010;5:e11356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vgontzas AN, Fernandez-Mendoza J, Liao D, Bixler EO. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration: the most biologically severe phenotype of the disorder. Sleep Med Rev. 2013;17:241–54. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kripke DF, Langer RD, Kline LE. Hypnotics' association with mortality or cancer: a matched cohort study. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e000850. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farkas RH, Unger EF, Temple R. Zolpidem and driving impairment--identifying persons at risk. New Engl J Med. 2013;369:689–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1307972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang NK, Harvey AG. Altering misperception of sleep in insomnia: behavioral experiment versus verbal feedback. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:767–76. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bianchi MT, Thomas RJ. Technical advances in the characterization of the complexity of sleep and sleep disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;45:277–86. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogilvie RD. The process of falling asleep. Sleep Med Rev. 2001;5:247–70. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2001.0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prerau MJ, Hartnack KE, Obregon-Henao G, et al. Tracking the sleep onset process: an empirical model of behavioral and physiological dynamics. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10:e1003866. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maes J, Verbraecken J, Willemen M, et al. Sleep misperception, EEG characteristics and Autonomic Nervous System activity in primary insomnia: a retrospective study on polysomnographic data. Int J Psychophysiol. 2014;91:163–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perlis ML, Merica H, Smith MT, Giles DE. Beta EEG activity and insomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 2001;5:363–74. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2001.0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wyatt JK, Bootzin RR, Allen JJ, Anthony JL. Mesograde amnesia during the sleep onset transition: replication and electrophysiological correlates. Sleep. 1997;20:512–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nofzinger EA, Buysse DJ, Germain A, Price JC, Miewald JM, Kupfer DJ. Functional neuroimaging evidence for hyperarousal in insomnia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2126–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bliwise DL, Friedman L, Yesavage JA. Depression as a confounding variable in the estimation of habitual sleep time. J Clin Psychol. 1993;49:471–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199307)49:4<471::aid-jclp2270490403>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fichten CS, Creti L, Amsel R, Bailes S, Libman E. Time estimation in good and poor sleepers. J Behav Med. 2005;28:537–53. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alameddine Y, Ellenbogen JM, Bianchi MT. Sleep-wake time perception varies by direct or indirect query. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11:123–9. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.4456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fernandez-Mendoza J, Shea S, Vgontzas AN, Calhoun SL, Liao D, Bixler EO. Insomnia and incident depression: role of objective sleep duration and natural history. J Sleep Res. 2015;24:390–8. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rioux I, Tremblay S, Bastien CH. Time estimation in chronic insomnia sufferers. Sleep. 2006;29:486–93. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.4.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edinger JD, Fins AI, Glenn DM, et al. Insomnia and the eye of the beholder: are there clinical markers of objective sleep disturbances among adults with and without insomnia complaints? J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:586–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosa RR, Bonnet MH. Reported chronic insomnia is independent of poor sleep as measured by electroencephalography. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:474–82. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200007000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonnet MH, Arand DL. Hyperarousal and insomnia: state of the science. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneider-Helmert D, Kumar A. Sleep, its subjective perception, and daytime performance in insomniacs with a pattern of alpha sleep. Biol Psychiatry. 1995;37:99–105. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)00162-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schabus M, Dang-Vu TT, Heib DP, et al. The fate of incoming stimuli during NREM sleep is determined by spindles and the phase of the slow oscillation. Front Neurol. 2012;3:40. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2012.00040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McKinney SM, Dang-Vu TT, Buxton OM, Solet JM, Ellenbogen JM. Covert waking brain activity reveals instantaneous sleep depth. PloS One. 2011;6:e17351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dang-Vu TT, McKinney SM, Buxton OM, Solet JM, Ellenbogen JM. Spontaneous brain rhythms predict sleep stability in the face of noise. Curr Biol. 2010;20:R626–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feige B, Al-Shajlawi A, Nissen C, et al. Does REM sleep contribute to subjective wake time in primary insomnia? A comparison of polysomnographic and subjective sleep in 100 patients. J Sleep Res. 2008;17:180–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Diekelmann S, Born J. The memory function of sleep. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:114–26. doi: 10.1038/nrn2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DeMartinis NA, Winokur A. Effects of psychiatric medications on sleep and sleep disorders. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2007;6:17–29. doi: 10.2174/187152707779940835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saletu B, Anderer P, Saletu M, Hauer C, Lindeck-Pozza L, Saletu-Zyhlarz G. EEG mapping, psychometric, and polysomnographic studies in restless legs syndrome (RLS) and periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD) patients as compared with normal controls. Sleep Med. 2002;3(Suppl):S35–42. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(02)00147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lal C, Strange C, Bachman D. Neurocognitive impairment in obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2012;141:1601–10. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lader M. Benzodiazepines revisited--will we ever learn? Addiction. 2011;106:2086–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]