Abstract

Acral melanoma (AM), as a peculiar subgroup of melanoma, is rare in Caucasians but has higher incidence in Asians. Large series of study on AM with clinicopathological features and prognostic factors is still limited, especially in Asian population. We retrospectively collected clinical, pathological and follow-up data of 142 AM cases. All patients were Chinese, with the age ranging from 24 to 87 years (mean 62.0; median 62.0). The Breslow thickness of primary lesions ranged from 0.6 to 16.3 mm (mean 4.9; median 3.7). 85.9% of the patients had acral lentiginous histologic subtype. Plantar was the most frequently involved site, followed by heels. Statistically, duration of the lesion before diagnosis (≤2.5 years), Breslow thickness >4.0 mm (T4), high mitotic index (>15 mm−2), presence of vascular invasion, regional lymph node metastasis at diagnosis and pathologic stage (II/III/IV) were found to be independent prognostic factors in both univariate and multivariate analyses. The prognosis of AM in Chinese is extremely poor. Our 5- and 10-year disease-specific survival (DSS) rates were 53.3% and 27.4%, respectively. Therefore, AM in Asians represents a more biologically aggressive melanoma subtype and is thought to carry a worse prognosis when compared with other races or cutaneous melanomas in other anatomic sites.

Malignant melanoma is the most lethal form of skin cancer and its incidence has considerably increased in recent decades in most countries. Based on the anatomical location and the degree of sun exposure, melanoma is classified into 4 major subtypes: melanoma on skin without chronic sun-induced damage, melanoma on skin with chronic sun-induced damage, mucosal melanoma, and acral melanoma (AM)1. The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data exhibited that the clinical features, anatomical origin, and patients’ prognoses differ significantly among different ethnic groups2. AM is rare in Caucasians (1–7%) but has higher incidence in non-White individuals3,4,5,6,7,8, accounting for up to 58% of all cutaneous melanomas in Asians9 and even more (60–70%) in Blacks10. It is often misdiagnosed or ignored before an accurate diagnosis is made because it is hidden from view11,12. Furthermore, AM may represent a more biologically aggressive melanoma subtype and is thought to carry a worse prognosis when compared with other melanoma subtypes12,13,14,15,16. However, only a few case series of AM has been published in Asia17,18 and knowledge on its characteristics and prognosis factors is still limited, especially in China which has the largest Asian population in the world. Herein, we present a large single-institution series of 142 patients with AM to identify clinical and pathological prognostic factors associated with disease-specific survival (DSS) for this peculiar subtype of melanoma.

Results

Clinical features

The clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. All the 142 patients were Chinese. There were 84 (59.2%) male patients and 58 (40.8%) female patients, with a male to female ratio of 1:0.69. The age of the patients at diagnosis ranged from 24 to 87 years (mean 62.0; median 62.0). Among 9 (6.3%) patients who recalled their exact trauma history, 5 were on the plantars, 4 were on the dorsum of the feet. Most trauma was caused by a mild injury, such as tearing on a stone, pricking on a spike or glasses, or stepping on charcoal. The diameter of the lesion, in terms of major axis, ranged from 0.3 to 7.5 cm (mean 2.5; median 2.0). The duration of the lesion before diagnosis was varied from 10 days to 70 years (mean 5.1 years; median 1.8 years).

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of Chinese patients with acral melanoma.

| Characteristics | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 84 (59.2) |

| Female | 58 (40.8) |

| Age, years | |

| <31 | 3 (2.1) |

| 31–40 | 4 (2.8) |

| 41–50 | 18 (12.7) |

| 51–60 | 37 (26.1) |

| 61–70 | 36 (25.4) |

| 71–80 | 34 (23.9) |

| >80 | 10 (7.0) |

| Trauma history | |

| Yes | 9 (6.3) |

| No | 133 (93.7) |

| Longest diameter of lesion, cm | |

| <1.0 | 8 (5.6) |

| 1.0–2.0 | 64 (45.1) |

| 2.0–3.0 | 37 (26.1) |

| 3.0–4.0 | 21 (14.8) |

| 4.0–5.0 | 6 (4.2) |

| >5.0 | 6 (4.2) |

| Duration of the lesion, years | |

| <1 | 45 (31.7) |

| 1–2.5 | 43 (30.3) |

| 2.5–5 | 24 (16.9) |

| 5–7.5 | 4 (2.8) |

| 7.5–10 | 5 (3.5) |

| >10 | 21 (14.8) |

| Site of lesion | |

| Nonungual location | 119 (83.8) |

| Finger | 4 (2.8) |

| Toe | 10 (7.0) |

| Foot | 105 (74.0) |

| Plantar | 59 (41.6) |

| Heel | 38 (26.8) |

| Dorsum | 8 (5.6) |

| Subungual location | 23 (16.2) |

| Fingernail | 7 (4.9) |

| Toenail | 16 (11.3) |

In the nonungual area, the plantar was the most common region. We did not find any case on the palms or the dorsum of the hands. In the subungual sites, the toenail is more frequently involved than the fingernail. The commonest location of subungual melanoma (SUM) was the great toe [13 lesions (56.5%)] followed by the thumb [5 lesions (21.7%)]. The lesions were distributed approximately equally between the right and the left side.

Manifestations of AM had a wide clinical spectrum. Lesions initially appeared as a pigmented macule, then progressed to a rapidly expanding plaque with irregular, notched borders, sometimes with ulceration (Fig. 1a). With the evolution of apparent vertical growth phase, an elevated papule or nodule developed within a background pigmented macule (Fig. 1b). Occasionally, multiple foci of satellites discontinuous from the main tumour were observed (Fig. 1c). In a minority of cases, it presented as achromic melanoma clinically resembling granuloma pyogenium (Fig. 1d). SUMs often began as brown to black discolouration of the nail that frequently became a well demarcated, pigmented longitudinal streak. With the time, the strip became bigger with indistinct, blurred margins (Fig. 1e). Thickening, splitting, or destruction of the nail plate may occur (Fig. 1f). The irregular macular hyperpigmentation can also spread to involve the skin of the digit, proximally, laterally and distally (Hutchinson sign, Fig. 1g). Eventually, the entire nail matrix and nail bed were occupied by a tan to black irregular plaque or mass, which involved the ungula fold and periungual skin (Fig. 1h).

Figure 1.

(a) AM on the heel, showing a rapidly expanding plaque with irregular margins and ulceration. (b) AM on the plantar, the tumorigenic vertical growth phase nodule is present within a background pigmented macule. (c) AM on the plantar, showing foci of satellites (arrows) discontinuous from the main irregular and pigmented lesion. (d) Achromic melanoma on the heel resembling granuloma pyogenium. (e) SUM showing pigmented strip on the index finger. (f) SUM on the little finger, thickening, splitting and destruction of the nail plate. (g) SUM on the thumb, spreading to the skin of the digit proximally, laterally, and distally (Hutchinson sign). (h) SUM on the great toe, the entire nail matrix and nail bed are occupied by irregular pigmented mass involving the ungual fold and periungual skin.

Histologic features and pathologic staging

Histologic examination was performed on 142 AM patients by wide surgical excision. Two patients (1.4%) had a personal history of a noncutaneous cancer (one liver, one pancreas). The Breslow thickness of the primary lesion ranged from 0.6 to 16.3 mm (mean 4.9; median 3.7). Of the 142 cases, the most common histologic subtype of patients were acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM) [122 cases (85.9%)] followed by nodular melanoma (NM) [17 cases (12.0%)] and superficial spreading melanoma (SSM) [3 cases (2.1%)]. Pathological characteristics, including Breslow thickness, Clark level, ulceration, mitotic rate, tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), vascular invasion, regional lymph node metastasis at diagnosis, and pathologic stage, are shown in Table 2. Some histologic characteristics of melanoma are shown in Fig. 2.

Table 2. Pathological characteristics of Chinese patients with acral melanoma.

| Characteristics | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Histologic subtype | |

| ALM | 122 (85.9) |

| NM | 17 (12.0) |

| SSM | 3 (2.1) |

| Breslow thickness, mm | |

| ≤1.0 | 8 (5.6) |

| 1.01–2.0 | 21 (14.8) |

| 2.01–4.0 | 55 (38.8) |

| >4.0 | 58 (40.8) |

| Clark level | |

| I | 1 (0.7) |

| II | 10 (7.0) |

| III | 3 (2.1) |

| IV | 83 (58.5) |

| V | 45 (31.7) |

| Ulceration | |

| Yes | 68 (47.9) |

| No | 74 (52.1) |

| Mitotic rate, mm−2 | |

| ≤15 | 131 (92.3) |

| >15 | 11 (7.7) |

| TILs | |

| Absent | 46 (32.4) |

| Brisk | 9 (6.3) |

| Non-brisk | 87 (61.3) |

| Vascular invasion | |

| Absent | 139 (97.9) |

| Present | 3 (2.1) |

| Regional lymph node metastasis at diagnosis | |

| Yes | 46 (32.4) |

| No | 96 (67.6) |

| Pathologic stage | |

| 0 | 1 (0.7) |

| I | 19 (13.4) |

| II | 74 (52.1) |

| III | 44 (31.0) |

| IV | 4 (2.8) |

ALM, acral lentiginous melanoma; NM, nodular melanoma; SSM, superficial spreading melanoma; TILS, tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes.

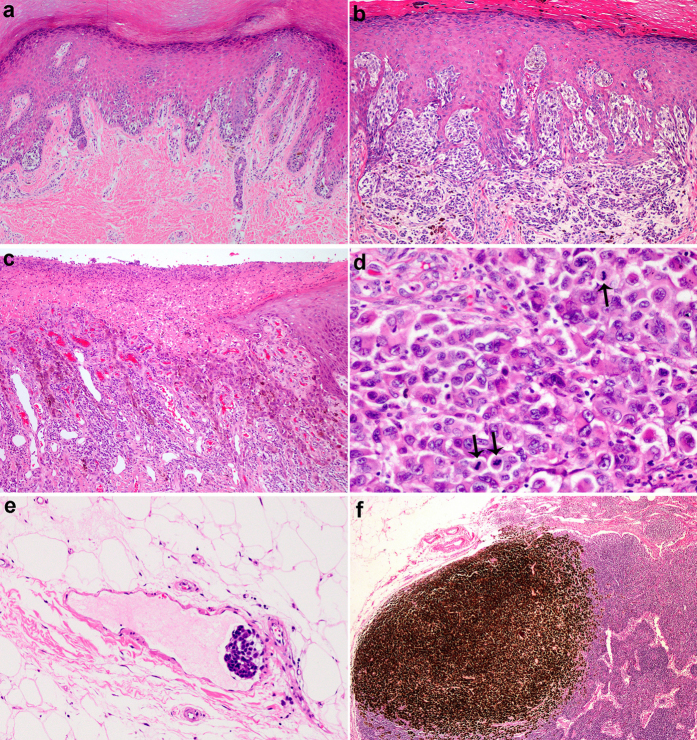

Figure 2.

(a) ALM in situ. Lentiginous proliferation of atypical melanocytes along the basal epidermis (original magnification ×100). (b) ALM with vertical growth phase, Clark level IV (original magnification ×100). (c) Ulceration (original magnification ×100). (d) Scattered mitoses in dermal lesion of melanoma (arrows) (original magnification ×400). (e) Vascular invasion by melanoma cells in septa of adipose tissue (original magnification ×200). (f) Melanoma metastasis with prominent pigment in regional lymph node (original magnification ×40).

Follow-up and survival analysis

The follow-up ranged from 5 to 151 months (mean 58.9; median 53.5). At the end of the study, 83 (58.5%) patients died of evolution of their melanoma, due to regional lymph node metastasis, in transit metastasis and/or distant metastasis (in brain, lung, liver, bone, bladder). 10 (7.0%) died of unrelated disease. 33 (23.2%) are alive without evidence of residual disease and 16 (11.3%) patients are alive after recurrence. The 5- and 10-year DSS rates were 53.3% and 27.4%, respectively. The 5-year DSS rates according to Breslow thickness are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Specific survival rates according to Breslow thickness.

| Overall | 5 year survival (%) |

|---|---|

| Thickness ≤1.0 mm | 100 |

| Thickness 1.01–2.0 mm | 66.7 |

| Thickness 2.01–4.0 mm | 56.4 |

| Thickness >4.0 mm | 27.6 |

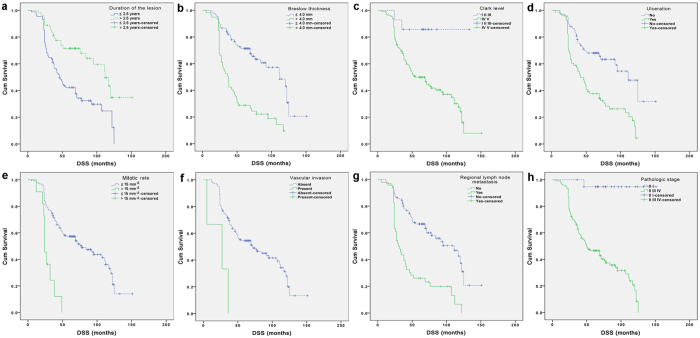

Univariate analysis revealed that patients with one of the following poor prognostic factors (Table 4): duration of the lesion before diagnosis (≤2.5 years), Breslow thickness >4.0 mm (T4), Clark level (IV/V), presence of ulceration, high mitotic rate (>15 mm−2), presence of vascular invasion, regional lymph node metastasis at diagnosis, pathologic stage (II/III/IV) had significantly lower DSS (Table 4, Fig. 3a–h). Then, the eight significant factors in univariate analysis were introduced in a multivariate Cox model to identify independent prognostic factors. Duration of the lesion before diagnosis (≤2.5 years), Breslow thickness >4.0 mm (T4), high mitotic rate (>15 mm−2), presence of vascular invasion, regional lymph node metastasis at diagnosis and pathologic stage (II/III/IV) were found to be independent prognostic factors for DSS (Table 5).

Table 4. Univariate analysis of factors associated with disease-specific survival in the acral melanoma cohort.

| Characteristics | No. Pts | No. of DOD (%) | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 142 | 83 (58.5) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 84 | 48 (57.1) | |

| Female | 58 | 35 (60.3) | 0.512 |

| Age, years | |||

| <55 | 41 | 26 (63.4) | |

| ≥55 | 101 | 57 (56.4) | 0.732 |

| Trauma history | |||

| Yes | 8 | 5 (62.5) | |

| No | 134 | 78 (58.2) | 0.486 |

| Longest diameter of lesion, cm | |||

| ≤2 | 72 | 42 (58.3) | |

| >2 | 70 | 41 (58.6) | 0.492 |

| Duration of the lesion, years | |||

| ≤2.5 | 88 | 61 (69.3) | |

| >2.5 | 54 | 22 (40.7) | <0.001 |

| Site of lesion | |||

| Nonungual location | 119 | 68 (57.1) | |

| Subungual location | 23 | 15 (65.2) | 0.895 |

| Histologic subtype | |||

| ALM | 122 | 67 (54.9) | |

| Other | 20 | 16 (80.0) | 0.081 |

| Breslow thickness, mm | |||

| ≤4.0 | 83 | 35 (42.2) | |

| >4.0 | 59 | 48 (81.4) | <0.001 |

| Clark level | |||

| I/II/III | 14 | 2 (14.3) | |

| IV/V | 128 | 81 (63.3) | 0.009 |

| Ulceration | |||

| Yes | 68 | 54 (79.4) | |

| No | 74 | 29 (39.2) | <0.001 |

| Mitotic rate, mm−2 | |||

| ≤15 | 131 | 73 (55.7) | |

| >15 | 11 | 10 (90.9) | <0.001 |

| TILs | |||

| Absent | 46 | 21 (45.7) | |

| Present | 96 | 62 (64.6) | 0.155 |

| Vascular invasion | |||

| Absent | 139 | 80 (57.6) | |

| Present | 3 | 3 (100.0) | 0.002 |

| Regional lymph node metastasis at diagnosis | |||

| Yes | 46 | 39 (84.8) | |

| No | 96 | 44 (45.8) | <0.001 |

| Pathologic stage | |||

| 0/I | 20 | 1 (5.0) | |

| II/III/IV | 122 | 82 (67.2) | <0.001 |

*Log-rank test; DOD, died of disease.

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier analyses of DSS for the entire group of patients according to different stratums by prognostic factors.

(a) Duration of the lesion. (b) Breslow thickness. (c) Clark level. (d) Ulceration status. (e) Mitotic rate. (f) Vascular invasion. (g) Regional lymph node status at diagnosis. (h) Pathologic stage.

Table 5. Multivariate analysis of factors associated with disease-specific survival in the acral melanoma cohort.

| Characteristics | HR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Duration of the lesion (≤2.5 vs >2.5) | 0.056 (0.332–0.930) | 0.025 |

| Breslow thickness (≤4.0 vs >4.0) | 1.749 (1.060–2.886) | 0.029 |

| Clark level (I II III vs IV V) | 1.188 (0.276–5.113) | 0.817 |

| Ulceration (Yes vs No) | 0.869 (0.524–1.442) | 0.588 |

| Mitotic rate (≤15 vs >15) | 2.399 (1.146–5.019) | 0.020 |

| Vascular invasion (Absent vs Present) | 0.272 (0.082–0.901) | 0.033 |

| Regional lymph node metastasis at diagnosis (Yes vs No) | 1.757 (1.105–2.792) | 0.017 |

| Pathologic stage (0 I vs II III IV) | 12.891 (1.689–98.425) | 0.014 |

Discussion

The present study is one of the largest single-institution series of AM with a complete review of the histological slides and with thorough follow-up of the patients in Asia. There was no significant sex predominance in our study, which is similar to the results in most previous studies12,13,14,16,17,18,19. However, a few studies of Whites reported a clear ALM predominance in females4,20. The mean age of our cohort was 62.0 years, with a peak incidence during the sixth decade (51–60 years). The mean age is comparable with data from other studies (55–63 years)4,12,13,14,16,18,20, while the peak age is slightly younger than that in most studies (61–70 or ≥70 years)14,18,20 of both Caucasians and Asians. Plantar was indicated as most frequently involved site in AM12,14,17,20. In accordance with previous reports, most AM in our series arose on the feet, most frequently on plantar sites (41.6%), followed by heels (26.8%). In our study, SUM was more frequent on toes (11.3%) than on fingers (4.9%). However, previous studies focusing on SUM indicated that it occurred more often on fingers than toes12,14,17,18,20,21. This could be due to our few cases of SUM.

Long delay with a duration ranging from 1 to 3.7 years in diagnosis of AM was described in the most representative reports19,22,23,24,25. Many factors seem to contribute to the postponement of diagnosis: elder patients, hidden site, frequent lack of pigmentation, lack of recognition and misdiagnosis by dermatologists sometimes. Clinical differential diagnoses for nonungual AM cases include wart, callus, fungal disorder, pyogenic granuloma et al. SUMs are often mistaken for chronic paronychia, subungual haematoma, keratoacanthoma, nonhealing ulcer, tinea et al. Interestingly and notably, our study demonstrated that patients with duration of the lesion before diagnosis (≤2.5 years) had significantly lower DSS. We considered that the tumour of shorter disease course may progress more rapidly and tends to be more aggressive than that of longer disease duration.

In the largest population-based evaluation of acral-lentiginous melanoma by Bradford et al., Asia/Pacific Islanders had the highest percentage of T4 compared to Whites and Blacks13. In consistent with previous data, our study indicated a high proportion of Breslow thickness of T4 (40.8%) and it is even higher than that reported in Koreans (33%)18. In addition, the mean Breslow thickness in our study was 4.9 mm, which is much more thicker than that in studies of Whites (2.0–2.6 mm)12,14,16,26. Therefore, we conclude that AM had a more advanced thickness in Asians, especially in Chinese. Furthermore, Breslow thickness (>4.0 mm) was a significant prognostic factor in both univariate and multivariate DSS analyses in our study. It was also indicated as an independent adverse prognostic factor in three of the four studies evaluating disease-free survival (DFS)12,20,27,28, and in three of the five studies evaluating overall survival (OS) or DSS12,16,20,29,30.

The proportion of ulceration (47.9%) in our series was higher than that previously described in both Asians and Whites (36–42%)4,14,16,18. In our study, ulceration was significantly associated with a lower DSS in univariate analysis, but did not show any significant effect in multivariate analysis. Other studies indicated that it has an independent prognostic value in one of the two studies evaluating DFS12,27 and in three of the four studies evaluating OS12,18,30 or DSS16. In addition, another prominent finding in our study was that high mitotic rate (>15 mm−2) appeared to be a powerful independent prognostic factor. The mitotic rate reflects the proliferative activity in a neoplastic system. There was only a few reports of AM that had done some research on it16,18,26. Only mitotic rate >6.0 mm−2 was found to be associated with a greater relative risk for short DFS and DSS in ALM study of Whites by Phan et al.26.

The prognosis of Chinese patients with AM was clearly not optimistic: The 5- and 10-year DSS rates in our patients were 53.3% and 27.4%, respectively. In the largest report of AM, Bradford et al. reported a population-based analysis, with 5- and 10-year DSS rates of 80.3% and 67.5%, respectively13. They also concluded that 5- and 10-year DSS rates were highest in non-Hispanic Whites (82.6% and 69.4%), intermediate in Blacks (77.2% and 71.5%), and lowest in Hispanic Whites (72.8% and 57.3%) and Asian/Pacific Islanders (70.2% and 54.1%). Bello et al. reported a 5-year DSS rate of 70%16, comparable with the rate reported by Kuchelmeister et al. (71%)14 and Phan et al. (76%)20. Our 5-year DSS results are substantially worse than those observed in AM (70–82%)14,16 and ALM (76–80%)19,20,26 of Whites. However, our data are comparable with those observed in other Asian studies. 5-year survival rates of AM reported from Korean and Japan ranged from 35.0% to 49.3%17,18. In addition, when controlling the survival rates for Breslow thickness, our 5-year DSS rates of AM were still 10–30% lower than those in previous studies13,19. So we concluded that the DSS rates of AM in Asians are worse than that in other races. Several factors including high ulcerative rate (47.9%), extreme proportion of Breslow thickness >4 mm (40.8%), high mitotic rate (>15 mm−2) may contribute to the poor survival in our patients. In addition, lack of recognition by patients and misdiagnosed as benign by clinicians sometimes can also contribute to the poor survival in our patients.

In conclusion, this study represents one of the largest single-institution series describing the clinicopathological characteristics and prognostic factors of AM in Asia. Duration of the lesion before diagnosis (≤2.5 years), Breslow thickness >4.0 mm (T4), Clark level (IV/V), presence of ulceration, high mitotic rate (>15 mm−2), presence of vascular invasion, regional lymph node metastasis at diagnosis and pathologic stage (II/III/IV) are prognostic indicators associated with DSS. As a particular subgroup of melanoma, the prognosis of AM in Asians is worse, compared with AM in other ethnic group and cutaneous melanomas in other sites.

Methods

Clinical data

The computerized databases in the pathology department of Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center were used for the study. The key words ‘melanoma’ were used to identify the patients. Among them, melanomas located on acral sites were included. Data were collected between January 2004 and December 2010 to allow determination of 5-year survival statistics. Only those patients with primary tumour and treated with wide surgical excision at our institution were included in our study. After reviewing the clinical records, pathological slides and complete follow-up data of these patients, 142 patients with AM were included in the present study. Informed consent was obtained from each patient. The study has been approved by Institutional Ethics Committee at Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center. All procedures were conducted according to the guidelines approved by Institutional Ethics Committee at Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center.

For each patient, the following clinical data were retrieved from medical records: sex, age at the time of diagnosis, the presence or absence of a history of trauma, longest diameter of lesion, duration of the lesion, and the site of lesion. The duration of the lesion was recorded as the time between the first notice by the patient of an abnormality and surgery-proven diagnosis. In case of incomplete or unavailable information, telephone interviews of the patients or of their families were systematically used. Clinical description of the primary lesion was based on clinical records and review of clinical preoperative photographs. For each patient, information on follow-up was recorded: clinical status at the latest contact (alive without evidence of recurrence, alive after recurrence, dead of the disease, dead of another disease). In addition, survival curves were calculated based on the medical records of patients who died of melanoma.

Histopathological study and pathologic staging

Pathological slides of surgical specimens were reviewed by two experienced dermatopathologists. The following data were recorded: histologic subtype, Breslow thickness, Clark level, ulceration, mitotic rate (mitotic count per millimeters squared), TILs, presence of vascular invasion, regional lymph node metastasis at diagnosis. The pathologic stage of disease was determined based on the most recent classification of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)31.

Statistical analysis

The evaluation of data was performed using the statistical package SPSS, version 22.0 (SPSS, Inc). The Kaplan-Meier method was used to calculate survival curves, and significant differences were determined by the log-rank test. DSS was defined as the time from pathological diagnosis to the time of death due to melanoma or last follow-up. Univariate Cox regression model was used to examine the association of clinical and pathologic variables with DSS. Characteristics significant on univariate analysis with a p value of <0.05 were entered into a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Lv, J. et al. Acral Melanoma in Chinese: A Clinicopathological and Prognostic Study of 142 cases. Sci. Rep. 6, 31432; doi: 10.1038/srep31432 (2016).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by Grants from Shanghai Natural Science (No. 12ZR1406600), Shanghai Hospital Development Center Emerging Advanced Technology Joint Research Project (HDC12014105) and Shanghai Key Developing Disciplines (2015ZB0201).

Footnotes

Author Contributions J.L. did statistical analysis and drafted the paper. B.D. revised the paper. Y.K. designed the study and revised the paper. X.S. collected the data and reviewed all the slides. J.K. reviewed all the slides. All authors reviewed the manuscript, and contributed to the final manuscript.

References

- Dai B. et al. Analysis of KIT expression and gene mutation in human acral melanoma: with a comparison between primary tumors and corresponding metastases/recurrences. Human pathology 44, 1472–1478 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormier J. N. et al. Ethnic differences among patients with cutaneous melanoma. Archives of internal medicine 166, 1907–1914 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw J. H. & Koea J. B. Acral (volar-subungual) melanoma in Auckland, New Zealand. The British journal of surgery 75, 69–72 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascinelli N. et al. Acral lentiginous melanoma. A histological type without prognostic significance. The Journal of dermatologic surgery and oncology 20, 817–822 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridgeway C. A., Hieken T. J., Ronan S. G., Kim D. K. & Das Gupta T. K. Acral lentiginous melanoma. Archives of surgery 130, 88–92 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard M. A. et al. Delays in diagnosis and melanoma prognosis (I): the role of patients. International journal of cancer 89, 271–279 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paladugu R. R., Winberg C. D. & Yonemoto R. H. Acral lentiginous melanoma. A clinicopathologic study of 36 patients. Cancer 52, 161–168 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cress R. D. & Holly E. A. Incidence of cutaneous melanoma among non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, Asians, and blacks: an analysis of california cancer registry data, 1988–93. Cancer causes & control 8, 246–252 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J. W. et al. Malignant melanoma in Taiwan: a prognostic study of 181 cases. Melanoma research 14, 537–541 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson D. A. & Krige J. E. Melanoma in black South Africans. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 180, 65–71 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman M. et al. Acral (volar-subungual) melanoma. The British journal of surgery 72, 610–613 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slingluff C. L. Jr., Vollmer R. & Seigler H. F. Acral melanoma: a review of 185 patients with identification of prognostic variables. Journal of surgical oncology 45, 91–98 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford P. T., Goldstein A. M., McMaster M. L. & Tucker M. A. Acral lentiginous melanoma: incidence and survival patterns in the United States, 1986–2005. Archives of dermatology 145, 427–434 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchelmeister C., Schaumburg-Lever G. & Garbe C. Acral cutaneous melanoma in caucasians: clinical features, histopathology and prognosis in 112 patients. The British journal of dermatology 143, 275–280 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack L. A. et al. Melanoma survival in the United States, 1992 to 2005. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 65, S78–S86 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello D. M. et al. Prognosis of acral melanoma: a series of 281 patients. Annals of surgical oncology 20, 3618–3625 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seui M. et al. Acral melanoma in Japan. The Journal of investigative dermatology 80, 56s–60s (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung H. J., Kweon S. S., Lee J. B., Lee S. C. & Yun S. J. A clinicopathologic analysis of 177 acral melanomas in Koreans: relevance of spreading pattern and physical stress. JAMA dermatology 149, 1281–1288 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boriani F., O’Leary F., Tohill M. & Orlando A. Acral Lentiginous Melanoma-misdiagnosis, referral delay and 5 years specific survival according to site. European review for medical and pharmacological sciences 18, 1990–1996 (2014). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan A. et al. Acral lentiginous melanoma: a clinicoprognostic study of 126 cases. The British journal of dermatology 155, 561–569 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan K. B. et al. Subungual melanoma: a study of 124 cases highlighting features of early lesions, potential pitfalls in diagnosis, and guidelines for histologic reporting. The American journal of surgical pathology 31, 1902–1912 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigby H. S. & Briggs J. C. Subungual melanoma: a clinico-pathological study of 24 cases. British journal of plastic surgery 45, 275–278 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T., Suetake T., Sugiyama Y., Tabata N. & Tagami H. Epidemiology and prognosis of subungual melanoma in 34 Japanese patients. The British journal of dermatology 134, 383–387 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn M. J., Thompson J. E., Crotty K., McCarthy W. H. & Coates A. S. Subungual melanoma of the hand. The Journal of hand surgery 21, 506–511 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papachristou D. N. & Fortner J. G. Melanoma arising under the nail. Journal of surgical oncology 21, 219–222 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan A. et al. Acral lentiginous melanoma: histopathological prognostic features of 121 cases. The British journal of dermatology 157, 311–318 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moehrle M. et al. “Functional” surgery in subungual melanoma. Dermatologic surgery 29, 366–374 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bormann G., Marsch W. C., Haerting J. & Helmbold P. Concomitant traumas influence prognosis in melanomas of the nail apparatus. The British journal of dermatology 155, 76–80 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes B. C., Seigler H. F., Saxby T. S., Kocher M. S. & Harrelson J. M. Melanoma of the foot. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume 76, 892–898 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton K. M., el-Naggar A., Ensign L. G., Ross M. I. & Balch C. M. Surgical management and prognostic factors in patients with subungual melanoma. Annals of surgery 219, 197–204 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balch C. M. et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 27, 6199–6206 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]