Abstract

The self-paced maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) test (SPV), which is based on the Borg 6-20 Ratings of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale, allows participants to self-regulate their exercise intensity during a closed-loop incremental maximal exercise test. As previous research has assessed the utility of the SPV test within laboratory conditions, the purpose to this study was to assess the effect of trial familiarisation on the validity and reproducibility of a field-based, SPV test. In a cross-sectional study, fifteen men completed one laboratory-based graded exercise test (GXT) and three field-based SPV tests. The GXT was continuous and incremental until the attainment of VO2max. The SPV, which was completed on an outdoor 400m athletic track, consisted of five x 2 min perceptually-regulated (RPE11, 13, 15, 17 and 20) stages of incremental exercise. There were no differences in the VO2max reported between the GXT (63.5±10.1 ml·kg-1·min-1) and each SPV test (65.5±8.7, 65.4±7.0 and 66.7±7.7 ml·kg-1·min-1 for SPV1, SPV2 and SPV3, respectively; P>.05). Similar findings were observed when comparing VO2max between SPV tests (P>.05). High intraclass correlation coefficients were reported between the GXT and the SPV, and between each SPV test (≥.80). Although participants ran faster and further during SPV3, a similar pacing strategy was implemented during all tests. This study demonstrated that a field-based SPV is a valid and reliable VO2max test. As trial familiarisation did not moderate VO2max values from the SPV, the application of a single SPV test is an appropriate stand-alone protocol for gauging VO2max.

Keywords: Field exercise, Maximal oxygen uptake, Ratings of Perceived Exertion, Reliability

INTRODUCTION

The self-paced maximal oxygen uptake ( max) test (SPV), which is based upon the Borg 6-20 Ratings of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale, allows participants to self-regulate their exercise intensity during a closed-loop incremental maximal exercise test. Laboratory-based SPV protocols have been shown to elicit higher [1–3] or comparable [4–6] max values to those reported from a conventional open-loop laboratory-based graded exercise test (GXT). Despite these findings, caution should be exercised with their interpretation as the reliability of the SPV protocol has yet to be examined. Enhanced reliability implies greater precision of one-off measures and better tracking of changes in measurements in research or practical settings [7].

The self-paced nature of exercising in an outdoor environment, where an individual is free to vary their pace, cannot be easily replicated in the laboratory environment [8]. The ecological validity of laboratory-based running protocols are reduced as the conscious decision to manually control the treadmill belt speed does not occur as quickly or as frequently as during self-paced running outside [9, 10]. As there are small but significant differences between running on a track and running on a treadmill due to variation in airstream, ground surface and movement patterns [8], the transferability of laboratory measurements to training and competitive situations may be limited. Accordingly, it is of interest to investigate the efficacy and reproducibility of the SPV in measuring max and the pace response during field-based exercise. Should the SPV prove to be reliable, this test may be of practical value to coaches when monitoring and prescribing exercise for athletes.

The purpose of this study was to assess the concurrent validity and reproducibility of a field-based SPV test in comparison to a conventional GXT. It was hypothesised that the SPV protocol would validly measure max and elicit reproducible findings in relation to max and the pacing response across three field-based SPV tests.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

This was a cross-sectional experimental study wherein fifteen men (23.9 ± 4.5 y, 1.74 ± 0.05 m, 73.9 ± 7.5 kg) who were recreationally-trained (>3 h·wk-1 of vigorous athletic training) participated in the study. Based on effect sizes (d z = 0.88) and mean (± SD) statistics for max [1], a minimum sample size of n = 12 was calculated to achieve a statistical power of 80% at an alpha level of .05. Participants were injury free, healthy and asymptomatic of any illness as confirmed through health screening procedures [11]. All participants had previous experience of undertaking maximal exercise testing in a laboratory environment, but none had completed the SPV test. Institutional ethical approval was obtained prior to the study in accordance with the spirit of the Helsinki Declaration, and participants provided written informed consent.

Procedures

Following basic anthropometric measurements, participants completed a laboratory-based GXT (19.6 ± 1.2 °C, 40.8 ± 5.1% [humidity], 1001.2 ± 8.3 hPa) on a motorised treadmill (True 825, Fitness Technologies, St Louis, USA). Subsequently, participants completed three field-based SPV exercise tests (SPV1, SPV2, SPV3), on an outdoor 400m athletics track at the same time of day (±1h) (19.8 ± 3.5 °C, 51.7 ± 13.9% [humidity], 1012.3 ± 6.3 hPa, 2.9 ± 2.1 km·h-1 [maximum wind speed]). All tests were separated by a 72h recovery period in which participants refrained from any normal training activities. Respiratory gases (oxygen uptake [], ventilation [], respiratory exchange ratio [RER]) were continuously measured using a portable breath-by-breath sampling system (K4-b-TX Module, Cosmed, Roe, Italy), and a global positioning system (GPS) watch (Suunto Ambit, Valimotie, Finland) was used to assess heart rate and the pacing response (using 5 s data averages) throughout each exercise test. Blood lactate (Lactate Pro, Kyoto, Japan) was assessed prior to and 1 min post each exercise test. Participants were perceptually anchored to the Borg 6-20 RPE scale [12] and to a 0-10 localized-leg-pain scale [13] by definition and recall procedures. By definition, participants were instructed that the differing numerical values equated to the feelings associated with the corresponding written definitions on each scale (e.g., RPE 20 equates to ‘maximal exertion’). Anchoring by recall refers to encouraging the participant to remember the range of feelings previously experienced during exercise of a similar nature (e.g., Pain 10 equates to an extremely intense pain). Physiological data (and treadmill speeds during the GXT) were masked from participants throughout both exercise tests.

During the GXT, max was confirmed by a visible plateau in oxygen consumption of ≤ 2 mL·kg-1·min-1 with a standard increment in exercise intensity, and / or any secondary criterion indicators (visible signs of exhaustion; HRmax ± 10 b·min-1; RER ≥ 1.15), at or around the point of volitional exhaustion [11]. The max value determined in the GXT was clarified using a verification stage [14]. Given the design and closed-loop nature of the SPV, whereby a nonlinear change in running speed is expected in the final stage of the test, the highest measure of was taken as the max, independent of changes in running speed.

Laboratory-based GXT

Participants initially completed a self-directed warm-up on the treadmill (2.5 min at a running speed equivalent to an RPE11; 2.5 min at an RPE13). The GXT commenced at the speed which was equivalent to RPE13 from the warm-up; a speed deemed sufficient to elicit max within 10 (±2) min [14]. The GXT was continuous and incremental, commencing at the chosen speed and increasing by 1 km·hr-1 every 2 min thereafter until volitional exhaustion. The treadmill gradient was set at 1% to reflect the energy cost associated with outdoor running [15]. During the final 20 s of each increment of the GXT, participants reported their overall RPE and localised pain perception. Following a 15 min recovery period, participants completed a max verification stage whereby speed was gradually increased over a 30 s period to a speed which was 1 km·hr-1 higher than the final stage of the GXT. Participants exercised at this elevated speed until volitional exhaustion. Respiratory markers were monitored throughout. Peak speed at max was the running speed at which max occurred, provided that the running time was greater than 1 min.

Field-based SPV

Following a similar warm-up to the GXT, participants commenced the SPV. This test was 10 min in duration and comprised five x 2 min stages of incremental exercise, which were adjusted according to prescribed RPE levels, equating to a light (RPE11), somewhat hard (RPE13), hard (RPE15), very hard (RPE17) and maximal RPE (RPE20). Participants were instructed to modify their running speed on a moment-to-moment basis in line with the prescribed RPE, rather than the end-point of the task, so that their RPE (not their speed) remained clamped for each given 2 min stage. The RPE scale was visible at regular intervals (every 100 m). During the final 20 s of each increment of the SPV, the researchers would show the exercise-induced pain scale to the participants whilst they were running to obtain their current perception of pain.

Following a 15 min recovery period, participants completed a max verification stage whereby participants repeated the final two, 2 min stages of the SPV test (RPE17 & RPE20). Respiratory markers were monitored throughout.

Statistical analysis

Breath-by-breath data (, VE, RER) from the GXT and SPV tests were averaged into 10 s bins and used in the following analyses. To assess the concurrent validity and reproducibility of the SPV, one-way ANOVAs compared the maximal physiological (max, HRmax, etc.), perceptual and physical (peak speed, average speed, distance, duration) data reported from the GXT to each SPV test (e.g., GXT vs. SPV1), and between each SPV test (e.g., SPV1 vs. SPV2). A Bland and Altman 95% limits-of-agreement (LoA) analysis quantified the agreement (bias ± random error [1.96 × SD]) between the max reported from the GXT and each of the SPV tests [16]. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were calculated to quantify the reproducibility of the maximal physiological criteria between the GXT and SPV tests, and between each of the SPV tests. A reliability coefficient (the smallest detectable difference) was also used to determine the critical difference in a parameter that must be exceeded between two sequential results in order for a statistically significant change to occur in an individual. A one-sample t-test was used to compare the maximal RPE from the GXT and SPV (RPE20).

To assess the pacing response during the SPV, two factor repeated measures ANOVA's; Test (SPV1, SPV2, SPV3) by RPE (RPE11, RPE13, RPE15, RPE17, RPE20) were used to compare the distance covered, and the peak, mean and end running speeds for each SPV test. Where significant differences were reported, Tukey's HSD was used to identify the location of any statistical differences (between SPV1, SPV & SPV3). A similar analysis was conducted to compare the coefficient of variation (CV) in running speed between each of the five perceptual intensities. The CV was calculated using the following equation:

Whereby, σ is the standard deviation of the running speed for a given perceptual intensity, and µ is the mean. Two-factor repeated measures ANOVAs were also used to assess the physiological responses (, HR, , RER) during the SPV tests. Partial eta squared () was used to demonstrate the effect size, with .0099, .0588 and .1379 representing a small, medium and large effect, respectively [17]. Partial eta squared was calculated using the following formula:

Whereby, SSEffect is the estimated variance for a given outcome measure, and SSError is the error variance that is attributable to the effect. Alpha was set at 0.05 throughout all analyses. All data were analysed using the statistical package SPSS for Windows, PC Software, version 22.

RESULTS

As there were no differences between max values reported from the GXT and SPV when compared to their corresponding verification test, the GXT and SPV data are used in the proceeding analyses.

Concurrent validity: GXT vs SPV 1, SPV 2, & SPV 3

There were no differences in the maximal physiological or perceptual values reported when comparing the GXT with each of the SPV tests (all P > .05; Table 1). Significant differences in average speed (F(3,56) = 20.54, P < .001, = .60) and total distance (F(3,56) = 3.601, P < .05, = .16) were however observed (Table 1). For the max reported from the GXT and SPV1, SPV2 and SPV3, the corresponding ICC and 95 % LoA were; 0.85 and 2.01 ± 13.26 ml·kg-1·min-1 (GXT vs. SPV1), 0.85 and 1.96 ± 12.28 ml·kg-1·min-1 (GXT vs. SPV2) and 0.87 and 3.27 ± 11.93 ml·kg-1·min-1 (GXT vs. SPV3, respectively).

TABLE 1.

Mean (± SD) physiological, perceptual and physical responses recorded at completion of the GXT and SPV tests.

| GXT | SPV1 | SPV2 | SPV3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VO2max (ml·kg-1·min-1) | 63.5 ± 10.1 | 65.5 ± 8.7 | 65.4 ± 7.0 | 66.7 ± 7.7 |

| VEmax (L·min-1) | 155 ± 17.2 | 161 ± 16.9 | 161 ± 16.5 | 163 ± 16.0 |

| HRmax (b·min-1) | 192 ± 6.8 | 191 ± 7.1 | 190 ± 8.0 | 191 ± 7.8 |

| Maximal RER | 1.00 ± 0.9 | 1.05 ± 0.1 | 1.01 ± 0.1 | 1.00 ± 0.1 |

| Maximal Blood Lactate (mmol·L-1) | 11.7 ± 3.1 | 11.0 ±2.5 | 10.3 ± 2.4 | 10.9 ± 2.0 |

| Maximal Pain | 8.4 ± 2.3 | 8.0 ± 2.5 | 7.7 ± 2.6 | 7.6 ± 2.6 |

| Maximal RPE | 19.8 ± 0.4 | 20 ± 0 | 20 ± 0 | 20 ± 0 |

| Peak Speed (km·h-1) | 17.7 ± 0.9 | 19.8 ± 2.5 | 18.9 ± 2.8 | 19.9 ± 2.9 |

| Average Speed (km·h-1) | 13.8 ± 1.0 | 14.4 ± 1.1* | 14.6 ± 1.1* | 15.0 ±1.2* |

| Total Distance (m) | 2620 ± 284.6 | 2389 ± 160* | 2425 ± 177 | 2462 ± 184 |

| Test Duration (sec) | 621 ± 43 | 600 ± 0 | 600 ± 0 | 600 ± 0 |

Note: *Significant difference between SPV and GXT (P < 0.001).

Reproducibility: SPV1 vs.SPV2 vs SPV3

There were no differences in the maximal physiological, perceptual or physical values reported when comparing the three SPV tests (all P > .05; Tables 1 and 2). Although RER and BLa provided low to moderate ICCs, all other parameters provided strong ICCs between SPV1 and SPV2, SPV2 and SPV3, and between all SPV tests (all ≥ 0.80).

TABLE 2.

Reliability of the physiological, perceptual and physical responses recorded from all SPV tests. Data is presented as the mean difference between tests, ICC, SEM and RC.

| SPV 1-SPV2 | SPV2-SPV3 | SPV1, SPV2 & SPV3 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Diff (±) SD | ICC | SEM | RC | Mean Diff (±) SD | ICC | SEM | RC | ICC | SEM | RC | |

| VO2max (ml·kg-1·min-1) | 0.05 ± 12.0 | 0.81 | 3.15 | 8.73 | -1.31 ± 12.0 | 0.92 | 2.07 | 5.74 | 0.80 | 3.16 | 8.77 |

| VEmax (L·min-1) | 0.27 ± 3.6 | 0.95 | 3.62 | 10.03 | 0.06 ± 3.6 | 0.97 | 2.91 | 8.06 | 0.94 | 3.87 | 10.73 |

| HRmax (b·min-1) | 0.7 ± 23.6 | 0.94 | 1.87 | 5.18 | -2.4 ± 23.6 | 0.98 | 1.12 | 3.10 | 0.94 | 1.88 | 5.20 |

| Maximal RER | 0.5 ± 10.6 | 0.35 | 0.04 | 0.12 | -0.3 ± 10.6 | 0.53 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| Maximal Blood Lactate (mmol·L-1) | 0.04 ± 0.12 | 0.66 | 1.17 | 3.25 | 0.02 ± 0.12 | 0.68 | 1.06 | 2.94 | 0.56 | 1.15 | 3.19 |

| Maximal Pain | 0.69 ± 3.6 | 0.94 | 0.64 | 1.77 | -0.55 ±3.6 | 0.99 | 0.23 | 0.65 | 0.94 | 0.63 | 1.75 |

| Peak Speed (km·h-1) | 0.9 ± 3.4 | 0.83 | 1.03 | 2.85 | -0.9 ± 3.4 | 0.88 | 0.93 | 2.56 | 0.81 | 1.10 | 3.04 |

| Average Speed (km·h-1) | -0.2 ± 1.6 | 0.92 | 0.30 | 0.84 | -0.4 ± 1.6 | 0.93 | 0.30 | 0.83 | 0.87 | 0.39 | 1.08 |

| Total Distance (m) | -36 ± 293 | 0.93 | 44.7 | 123.9 | -37 ± 293 | 0.95 | 38.9 | 107.7 | 0.90 | 54.5 | 151.1 |

Note: ICC, Intraclass correlation coefficients; SEM, Standard error of the mean; RC, Reliability coefficient

Pacing response during SPV tests

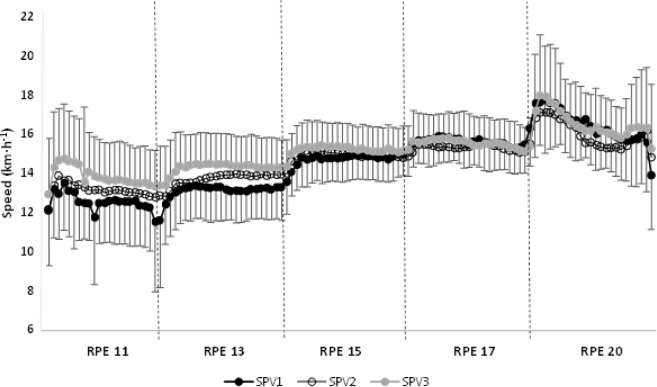

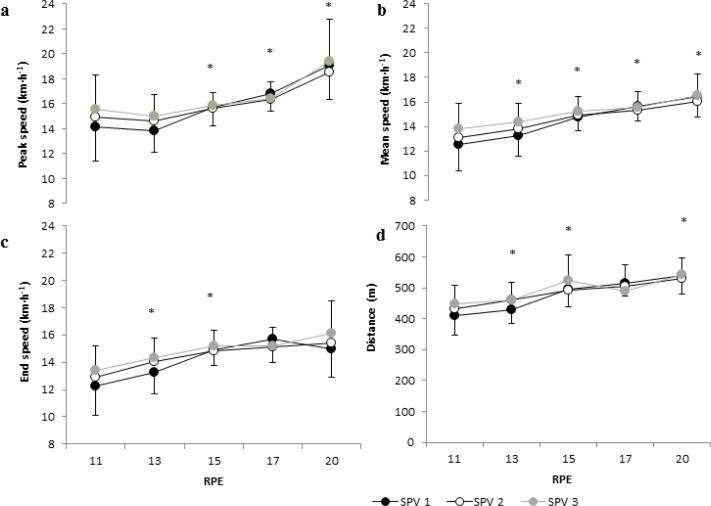

Figure 1 demonstrates the mean (±SD) pacing strategy at each perception of exertion for SPV1-SPV3. There were no Test by RPE interactions for the peak speed, mean speed, end speed and for the distance ran from the SPV tests (all P > .05; Figure 2). Similar findings were observed when considering the CV for running speed (F(3.1,42.7) = 1.44, P > .05, = .09; Table 3). An RPE main effect was observed for peak (F(1.4,19.1) = 18.06, P < .001, = .56), mean (F(1.4,19.6) = 26.69, P < .001, = .66) and end speed (F(2.1,29.4) = 16.95, P < .001, = .55), and for the distance ran (F(2.3,32) = 23.47, P < .001, = .63), with significant increases occurring at various increments in exercise intensity (all P <.01; Figure 2). For the CV in running speed, significant changes were only observed between RPE11 and RPE13 (F(1,14) = 18.5, P < .01, = .57) and RPE17 and RPE20 (F(1,14) = 14.1, P < .01, = .50; Table 3).

FIG. 1.

Pacing response, 5 second averages for SPV 1, SPV 2 and SPV 3 at RPE 11, RPE 13, RPE 15, RPE 17 and RPE 20.

FIG. 2.

Mean (± SD) peak speed (2a), mean speed (2b), end speed (2c) and distance (2d) reported at RPE 11, 13, 15, 17 and 20 from the three SPV tests.

TABLE 3.

The coefficient of variation (mean ± SD) for each perceptual intensity (RPE11, RPE13, RPE15, RPE17 & RPE20) and SPV test.

| SPV1 | SPV2 | SPV3 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPE 11 | 7.9 ± 5.9 | 4.8 ± 2.8 | 6.4 ± 4.2 | 6.4 ± 3.1* |

| RPE 13 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 3.0 ± 1.7 | 2.9 ± 1.2 | 2.9 ± 1.1 |

| RPE 15 | 3.3 ± 1.0 | 3.1 ± 1.6 | 2.3 ± 0.9 | 2.9 ± 0.8 |

| RPE 17 | 4.1 ± 1.6 | 3.2 ± 1.5 | 2.9 ± 1.3 | 3.5 ± 1.1 |

| RPE 20 | 8.7 ± 4.8 | 7.5 ± 5.4 | 7.7 ± 6.3 | 8.0 ± 5.0# |

Note: *Significantly higher coefficient of variation than proceeding stage (RPE 13; P < .01),

Significantly higher coefficient of variation than preceding stage (RPE 17; P < .01).]

Significant Test main effects were observed for peak (F(2,28) = 4.35, P < .05, = .24), mean (F(1.4,19.4) = 7.88, P < .01, = .36) and end speed (F(2,28) = 6.05, P < .01, = .30), and distance ran (F(2,28) = 6.35, P < .01, = .31), with participants in SPV3 running, on average, faster and further than both SPV1 and SPV2.

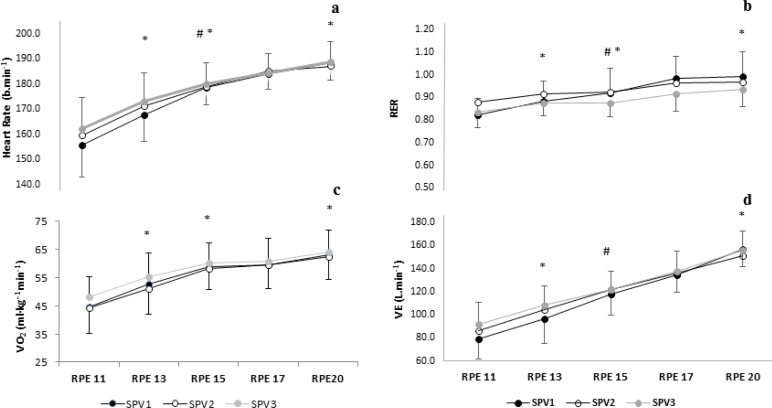

Physiological response during SPV tests

A significant Test by RPE interaction was observed for HR (F(4.3, 60.1) = 4.19, P < .05, = .23), · (F(8,112) = 3.98, P < .001, = .22) and RER (F(2.8,39.1) = 3.19, P < .05, = .19; Figure 3). During SPV1, participants experienced a greater change in HR, · and RER between RPE13 and RPE15 than either SPV2 or SPV3. RPE main effects were observed for , HR, , RER and pain (all P <0.001; Figure 3).

FIG. 3.

Mean (± SD) HR (3a), RER (3b), VO2 (3C) and VE (3d) at RPE 11, 13, 15, 17 and 20 for SPV1, SPV2 and SPV3

DISCUSSION

This study assessed the validity and reproducibility of a field-based self-paced max test in recreationally-trained men. In this study, SPV1, SPV2 and SPV3 elicited similar max values to those obtained from a traditional laboratory-based GXT. Accordingly, and in support of the study hypotheses, a field-based SPV test may be considered a valid test of max, in keeping with previous laboratory-based research [4–6]. Furthermore, the SPV test was considered reliable, as a period of trial familiarisation did not statistically moderate the max or pacing response elicited.

Despite no statistical differences and a high correlation (ICC: 0.85-0.87) between the GXT and the three SPV tests, slightly higher max values were observed with the SPV (3.1%, 3.0% & 4.8% for SPV1, SPV2 & SPV3, respectively), similar to past research [1, 2, 5]. This is pertinent from a coach's perspective as positive changes in aerobic capacity in the region of 3-5% have been accepted as a meaningful performance improvement [18, 19]. Therefore, it is important to recognise: i) the practical implications of measuring an athlete's maximal aerobic capacity using differing methods of assessment, and ii) that the SPV may consistently elicit higher practical values than a laboratory-based GXT. However, it should be noted that near optimal environmental conditions were experienced in the course of the field data collection (e.g., wind speed ≤ 3 ms-1) and thus, our findings should be considered in the context of this. Furthermore, as there appears to be a difference in max that is of practical significance, it is likely that the non-statistical difference in max between the GXT and SPV in the current study was due to the wide variance associated with the fitness level of the participants recruited (i.e., recreationally-trained). Future research should therefore ensure that participants are more closely matched for fitness when assessing the validity and reliability of the SPV protocol.

In this study, a mean difference in max of 0.05 mL·kg-1·min-1 (0.2%) and 1.3 mL·kg-1·min-1 (1.8%) was observed between SPV1 and SPV2, and SPV2 and SPV3, respectively. This is encouraging when considering that laboratory-based maximal exercise tests have shown a 3 to 6% variation in max values following three or more repeated trials [19, 20]. The reliability of the SPV protocol is further demonstrated using ICC (all >0.80), SEM and RC analyses for max and other variables of interest (Table 2). Accordingly, this study confirms that the application of a single SPV, which to date, has been the only way the test has been implemented previously [1–6], may be appropriate for gauging max. However, as the ICC and RC's were shown to improve with trial familiarisation (Table 2), and as participants ran, on average, faster and further during SPV3 than either SPV1 (4.3 & 3.1%, respectively) or SPV 2 (2.8 & 1.6%, respectively), there may be benefit in repeat assessments.

Despite the positive max findings, it is an athlete's running speeds and pacing response at differing submaximal intensities that are perhaps more pertinent for training prescription. In this study, participants’ changes in speed (peak, mean and end speed) and distance between the five stages of the SPV protocol were similar between SPV1, SPV2 and SPV3 (see Figure 2). Although a more variable running speed was observed at the start (RPE11) and end (RPE20) of each SPV (Table 3), a similar overall pacing response was observed between the three trials. Each of the perceptual intensities corresponded to 66-69% (RPE11), 69-73% (RPE13), 75-79% (RPE15) and 78-82% (RPE17) of the peak running speed observed from the max test. Knowledge of the speed, distance and heart rate responses at submaximal and maximal SPV stages may be a useful reference for coaches when determining and prescribing appropriate training intensities, negating the need for expensive equipment, designated laboratory facilities and trained technicians associated with traditional, maximal GXT protocols.

Regardless of the SPV test, the pacing response varied within SPV protocols. Although continuous increments in peak running speed were observed after RPE13, there were no differences in the peak running speed between RPE11 and RPE13 (Figure 2a). The mean speed and end speed for RPE11 was however lower than RPE13 (Figure 2b & 2c), suggesting that participants adopted an inappropriate starting speed (e.g. ran too fast) at the start of the protocol. In this regard, it is plausible that afferent feedback involving physiological systems, environmental surroundings and psychological constructs (mood, self-efficacy, etc.) helped to adjust the pacing response after the initial peak speed was achieved to ensure that an appropriate running speed was elicited thereafter. This appears to be corroborated by the CV in running speed, which demonstrated a more variable pacing response at RPE11 compared to RPE13 (6.4 ± 3.1 vs. 2.9 ± 1.1%, respectively).

Knowledge of the exercise end-point has been suggested to be the single most important factor in influencing a pacing strategy [21]. In this study, a more conservative pacing strategy was observed during the latter portion (RPE15 & RPE17) of the SPV (Figure 2). This finding is complemented by the physiological data, as similar , HR, and RER values were reported between RPE15 and RPE17 (Figure 3). The anticipated 2 min maximal sprint at RPE20 may have encouraged participants to utilise a more conservative pacing strategy during the final moments of the penultimate stage of the exercise test. Similar findings have been shown elsewhere [3, 22, 23]. For example, Sperlich et al. [23] demonstrated that when participants could manipulate both treadmill speed and inclination throughout a self-selected maximal exercise test, participants often elicited a rapid change in one or both of these factors in the final few minutes of the exercise test. In the present study, it is also of interest to note that RPE20 elicited a greater CV in running speed than RPE17 (Table 3). The greater variation at RPE20 is likely due to the rapid increase and attempted maintenance of peak speed during this stage, stimulating a greater accumulation of metabolic by-products, and thus facilitating a greater perception of pain and discomfort than that associated with RPE17. Consequently, the SPV protocol may be better suited to experienced athletes as it may reflect the physiological and pacing demands encountered during competition.

The researchers do recognise certain limitations to the study. In the present study, participants completed their laboratory-based GXT prior to any of the field-based SPV tests. To minimise the risk of any potential confounding effects associated with test order, it would have been useful to implement a randomised and counterbalanced crossover design. Our study also compared the physiological, physical and perceptual responses between treadmill and over-ground running.

As kinematic [24, 25] and perceptual [26] differences may be evident between these ambulatory modalities, it may be speculated that these differences could have contributed to some of the statistical differences reported in Table 1. Similar to Hogg and colleagues [3], the lack of difference in peak running speed between the treadmill GXT and the field-based SPV may be due to limitations in achieving a ‘true’ peak running speed during treadmill exercise, which in-turn may confound the validity of the reported findings.

CONCLUSIONS

This is the first study to demonstrate the concurrent validity and reliability of a field-based SPV. Measures of max in the field-based SPV were not statistically different from those in the laboratory-based GXT, and trial familiarisation did not moderate the max values from the SPV. Thus, a single SPV test is considered appropriate for max assessment in the field. In addition, knowledge of the speed, distance and heart rate responses at submaximal and maximal SPV stages may provide useful points of reference for coaches when determining and prescribing appropriate training intensities, without the need for expensive equipment in the measurement of max. Future research should consider assessing the validity and reliability of the field-based SPV in participant groups of differing levels of fitness.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Massey University Summer Scholarship scheme for supporting the costs of the study.

Conflict of interests

The authors declared no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mauger AR, Sculthorpe N. A new VO2max protocol allowing self-pacing in maximal incremental exercise. Bri J Sports Med. 2012;46:59–63. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mauger AR, Metcalfe AJ, Taylor L, Castle PC. The efficacy of the self-paced VO2max test to measure maximal oxygen uptake in treadmill running. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2013;38:1211–1216. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2012-0384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hogg JS, Hopker JG, Mauger AR. The Self-Paced VO2max Test to Assess Maximal Oxygen Uptake in Highly Trained Runners. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2015;10:172–77. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2014-0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chidnok W, Dimenna FJ, Bailey SJ, Burnley M, Wilkerson DP, Vanhatalo A, Jones AM. VO2max is not altered by self-pacing during incremental exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2013;113:529–539. doi: 10.1007/s00421-012-2478-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faulkner J, Mauger A, Woolley B, Lambrick D. The efficacy of a self-paced VO2max test during motorised treadmill exercise. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2015;10:99–105. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2014-0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Straub AM, Midgley AW, Zavorsky GS, Hillman AR. Ramp-incremented and RPE-clamped test protocols elicit similar VO2max values in trained cyclists. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2014;114:1581–90. doi: 10.1007/s00421-014-2891-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hopkins WG. Measures of reliability in sports medicine and science. Sports Med. 2000;30:1–15. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200030010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyer T, Welter JP, Scharhag J, Kindermann W. Maximal oxygen uptake during field running does not exceed that measured during treadmill exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2003;88:387–389. doi: 10.1007/s00421-002-0718-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowtell MV, Tan H, Wilson AM. The consistency of maximum running speed measurements in humans using a feedback-controlled treadmill, and a comparison with maximum attainable speed during overground locomotion. J Biomech. 2009;42:2569–2574. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Smet K, Segers V, Lenoi M, De Clercq D. Spatiotemporal characteristics of spontaneous overground walk-to-run transition. Gait Posture. 2009;29:54–58. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borg G. Borg's Perceived Exertion and Pain Scales. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cook DB, O'Connor PJ, Eubanks SA, Smith JC, Lee M. Naturally occurring muscle pain during exercise: assessment and experimental evidence. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29:999–1012. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199708000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hawkins MN, Raven PB, Snell PG, Stray-Gundersen J, Levine BD. Maximal oxygen uptake as a parametric measure of cardiorespiratory capacity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:103–107. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000241641.75101.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones AM, Doust JA. 1% treadmill grade most accurately reflects the energetic cost of outdoor running. J Sport Sci. 1996;14:321–327. doi: 10.1080/02640419608727717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beltrami FG, Froyd C, Mauger AR, Metcalfe AJ, Marino F, Noakes TD. Conventional testing methods produce submaximal values of maximum oxygen consumption. Brit J Sport Med. 2012;46:23–29. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirkeberg JM, Dalleck LC, Kamphoff CS, Pettitt RW. Validity of 3 Protocols for Verifying VO2max. Int J Sports Med. 2011;32:266–270. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1269914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lourenco TF, Martins LEB, Tessutti LS, Brenzikofer R, Macedo DV. Reproducibility of an incremental treadmill VO2max test with gas exchange analysis for runners. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25:1994–1999. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e501d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mauger AR, Jones AM, Williams CA. Influence of feedback and prior experience on pacing during a 4-km cycle time trial. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41:451–458. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181854957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Astorino TA, McMillan DW, Edmunds RM, Sanchez E. Increased cardiac output elicits higher VO2max in response to self-paced exercise, Appl Physiol. Nutr Metab. 2014;40:223–229. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2014-0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sperlich PF, Holmberg HC, Reed JL, Zinner C, Mester J, Sperlich B. Individual versus standardized running protocols in the determination of VO2max. J Sports Sci Med. 2015;14:386–393. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nigg BM, De Boer RW, Fisher V. A kinematic comparison of overground and treadmill running. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27:98–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schache AG, Blanch PD, Rath DA, Wrigley TV, Starr R, Bennell KL. A comparison of overground and treadmill running for measuring the three-dimensional kinematics of the lumbo–pelvic–hip complex. Clin Biomech. 2001;16:667–680. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(01)00061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kong PW, Koh TM, Tan WC, Wang YS. Unmatched perception of speed when running overground and on a treadmill. Gait Posture. 2012;36:46–48. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]