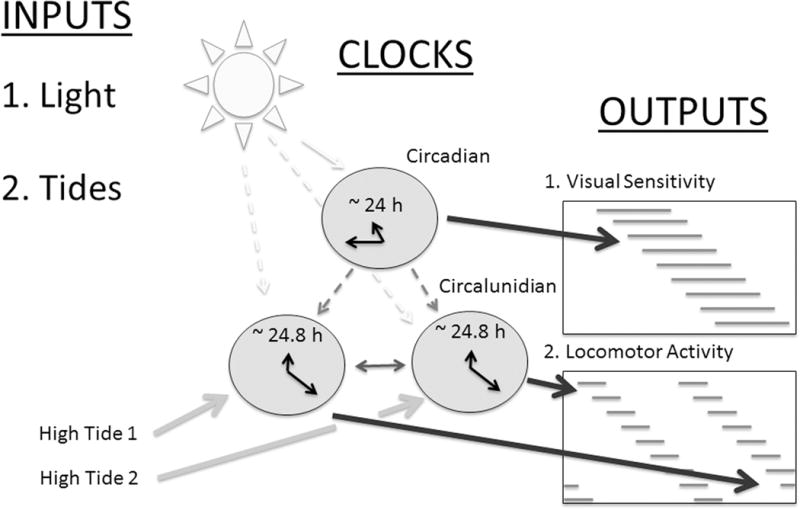

Figure 5.

Proposed model of the circalunidian system of the American horseshoe crab. Solid lines – demonstrated influences; dashed lines – hypothesized influences. While the day/night light cycles entrains the circadian clock (Solid white arrow: Barlow, 1983; Watson et al., 2008), each circalunidian clock is entrained by the two different daily tides (Solid gray arrow: Chabot et al., 2011; Figure 1). In turn, the circadian clock drives a single cycle of eye sensitivity each day (Solid black arrow: Watson et al., 2008) while each circalunidian clock drives a separate daily bout of (circatidal) activity ((Solid black arrows: Chabot and Watson, 2010; Figs. 1–4). In this model, LD cycles (or circadian clocks) are hypothesized to influence circatidal rhythms by influencing the circalunidian clocks. Circatidal rhythms are affected by LD cycles in a number of intertidal species (Sesarma pictum, Saigusa, 1992; Uca sp., Stillman and Barnwell, 2004; Limulus, Chabot and Watson, 2004; Chabot et al., 2007), but it is currently unclear if these are direct effects of LD or are mediated through inputs from circadian clocks. The LD (or circadian)-driven silencing of one, but not the other, bout of activity (Chabot and Watson, 2010) may be responsible for the appearance of “skipping” (Fig. 1 – middle panel; Figs. 2 and 3, bottom panels, last several days; Fig. 4 – all panels – last several days).