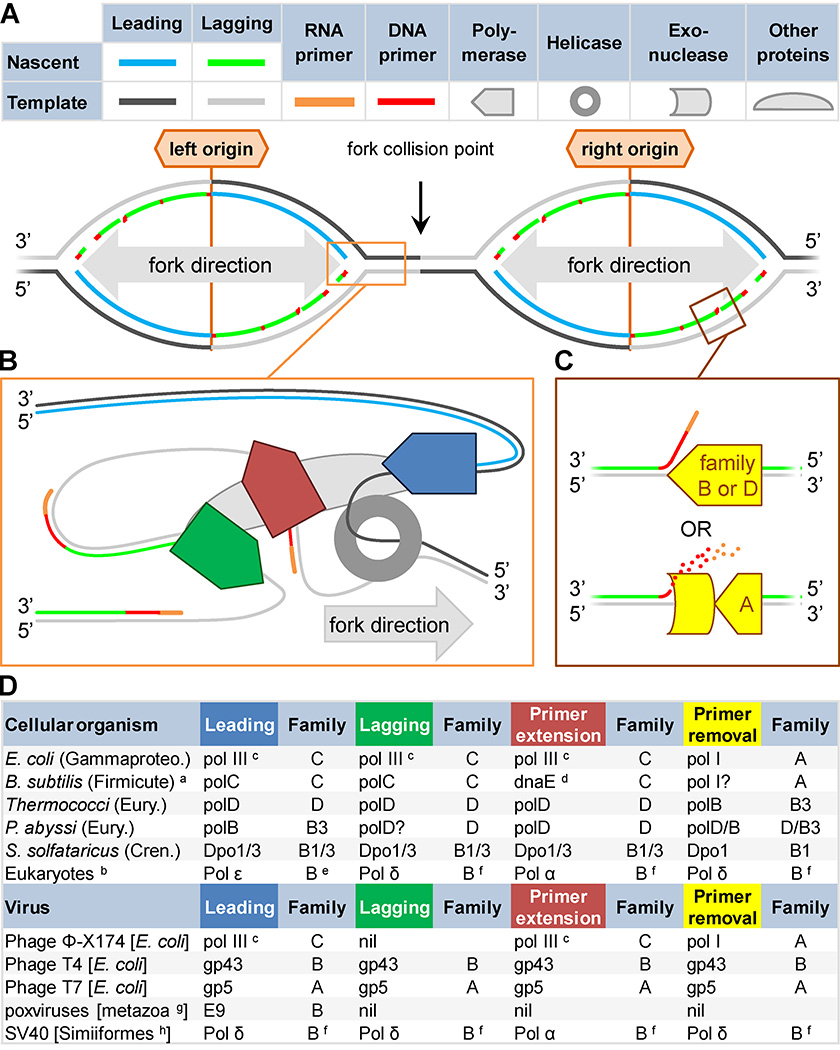

Figure 2. Organisms cope with the demands of simultaneous continuous and discontinuous replication in diverse ways.

A) Inherent DNA asymmetry and obligate 5’-to-3’ directional synthesis mean that one nascent strand (leading; blue) is synthesized continuously while the other (lagging; green) is synthesized in short discontinuous stretches (Okazaki fragments), creating a forked structure (orange box). Synthesis is initiated with an RNA primer (orange), followed by a short DNA primer (red), at replication origins (labeled). Efficiency dictates that two forks proceed in opposite directions from each origin (bidirectional), resulting in collisions (black arrow). B) Replicases (pentagons) can specialize in different replicative roles: extension from the RNA primer (red); discontinuous Okazaki fragment synthesis (green); or continuous leading strand synthesis (blue). C) Polymerases may specialize in synthesis during primer removal (yellow shapes), either through primer displacement or exonucleolysis. D) Replicases are diverse. Polymerase family (A–D), and subfamily (e.g. B3) are indicated. Viral hosts are listed in square brackets. Except in eukaryotes and Escherichia coli, most analyses of polymerase roles in cellular organisms have relied on inferences based on in vitro capabilities. Superscripts: a, not typical of all Firmicutes, Clostridia not shown; b, most studied in Saccharomyces cerevisiae; c, class dnaE1; d, class dnaE3; e, possibly B1 or B2; f, possibly B3; g, observed in vertebrates and arthropods; h, monkeys and apes. Abbreviations: Gammaproteo.→Gammaproteobacteria; B.→Bacillus; Eury.→Euryarchaeota; Chren.→Crenarchaeota; P.→Pyrococcus; S.→Sulfolobus.