Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine the effect of regular exercise training on insulin sensitivity in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) using the pooled data available from randomised controlled trials. In addition, we sought to determine whether short-term periods of physical inactivity diminish the exercise-induced improvement in insulin sensitivity. Eligible trials included exercise interventions that involved ≥3 exercise sessions, and reported a dynamic measurement of insulin sensitivity. There was a significant pooled effect size (ES) for the effect of exercise on insulin sensitivity (ES, –0.588; 95% confidence interval [CI], –0.816 to –0.359; P<0.001). Of the 14 studies included for meta-analyses, nine studies reported the time of data collection from the last exercise bout. There was a significant improvement in insulin sensitivity in favour of exercise versus control between 48 and 72 hours after exercise (ES, –0.702; 95% CI, –1.392 to –0.012; P=0.046); and this persisted when insulin sensitivity was measured more than 72 hours after the last exercise session (ES, –0.890; 95% CI, –1.675 to –0.105; P=0.026). Regular exercise has a significant benefit on insulin sensitivity in adults with T2DM and this may persist beyond 72 hours after the last exercise session.

Keywords: Aerobic training, Glucose tolerance test, Hyperinsulinaemic euglycaemic clamp, Insulin resistance, Resistance training

INTRODUCTION

Exercise is an integral component of the lifestyle management of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Current exercise guidelines recommend that adults with T2DM should undertake aerobic-type exercise at moderate and/or vigorous intensity on 3 to 5 days per week, ideally combined with regular vigorous progressive resistance training (PRT) [1,2]. Meta-analyses have demonstrated that this dose of regular exercise is effective in improving glycaemic control as measured by change in glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) in diabetic cohorts [3].

Insulin resistance itself has been shown to significantly increase the incidence and prevalence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in individuals with T2DM [4]. For instance, in a longitudinal study which monitored CVD in individuals with T2DM, each unit increase in homeostasis model of insulin resistance was associated with a 31% greater risk of CVD (odds ratio [OR], 1.48), and a 56% elevated risk of CVD in individuals who were followed-up at 52 months (OR, 2.24) [4]. In a study which examined insulin-stimulated glycaemic control in healthy individuals over a 4 to 11 years period, greater insulin resistance was associated with an increased incidence of age-related chronic conditions including hypertension, coronary heart disease, stroke, and cancer [5]. Thus insulin resistance itself has a significant detrimental impact on health and the development of chronic disease.

The role of chronic versus acute factors in accounting for the insulin sensitizing benefit of exercise is unclear, and this has implications for the use of exercise in the management of T2DM. For instance, exercise increases insulin-mediated glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) translocation to the sarcolemma and subsequent glucose uptake, which may reflect a transient elevation as a consequence of the "last bout" [6]. The underlying increase in GLUT4 transcription and expression of GLUT4 mRNA has been shown to persist for 3 to 24 hours after exercise [7,8]. In this way, regular exercise translates into a steady-state increase of GLUT4 protein expression, and subsequent improvement in glucose control over time [7]. Similarly, enhanced whole-body insulin sensitivity has been shown to occur in the hours immediately following exercise, and evidence from a limited number of studies using hyperinsulinaemic-euglycaemic clamp and oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) suggests that this may persist for up to 24 to 72 hours after the last bout [1,9,10]. Current guidelines reflect this concept of a transient benefit that may be "lost," by recommending that consecutive days of physical inactivity should be avoided [1,2].

However, while there is evidence that supports the use of exercise as a management strategy to control HbA1c and fasting insulin in T2DM, these static measurements do not directly evaluate the underlying insulin sensitivity [11]. To our knowledge, there is limited data concerning the effect of regular exercise on dynamically measured insulin sensitivity in people with T2DM [1,12], and no systematic examination and meta-analysis of the pooled evidence has been undertaken.

The purpose of this study was to examine the effect of regular exercise training on insulin sensitivity in people with T2DM using the collective data available from randomised controlled trials (RCTs). In addition, we sought to determine whether short-term (days) periods of physical inactivity diminish the exercise-induced improvement in insulin sensitivity in adults with T2DM.

METHODS

Design

Electronic database searches were performed in AMED, MEDLINE, SPORTDiscus, CINAHL, EMBASE, and Web of Science Core Collections from earliest record to December 2014. The search strategy combined terms covering the areas of aerobic exercise training, strength training, and insulin sensitivity. Specifically, the database searches were performed using the keywords: strength training, weight training, resistance training, progressive training, progressive resistance, weight lifting; or aerobic exercise, endurance exercise, aerobic training, endurance training, cardio training, exercise, physical endurance, physical exertion; and insulin sensitivity, insulin resistance, tolerance test, OGTT, ITT, IVGTT, MTT, IST, clamp. The latter terms refer to oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), insulin tolerance test (ITT), intravenous glucose tolerance test (IVGTT), meal tolerance test (MTT), and insulin secretion test (IST), respectively.

Reference lists of all retrieved papers were manually searched for potentially eligible papers. RCTs published in all languages were included while non-RCTs, uncontrolled trials, cross-sectional studies, and theses were excluded from review.

Interventions

Studies were included if the exercise training intervention involved three or more exercise sessions. Trials where participants were randomised to an intervention involving either aerobic exercise (i.e., continuous, intermittent, or high intensity interval training [HIIT]) (aerobic exercise training [AEx]) or PRT, or combined (AEx+PRT), were included. Studies involving dietary interventions were included only if the diet was the same in the exercise and control groups.

Participants

Trials that were completed with individuals with T2DM, who were of 18 years or older, were included in the review.

Outcome measures

Trials that were eligible for the review reported measurements that assessed dynamic insulin sensitivity. Measures that were considered as dynamic assessments of insulin sensitivity evaluated the glucose response to insulin/glucose stimulation. To be eligible for review, studies needed to report the change in glucose based on the dynamic insulin sensitivity assessment.

Clamps: euglycaemic clamp

Glucose levels are clamped and titrated at a predetermined level, in conjunction with continuous insulin infusion at a fixed rate. It is considered the gold standard measure for insulin resistance [13]. Blood concentrations are measured every 3 to 5 minutes. Insulin resistance is determined by the rate/amount of glucose that is necessary to maintain the predetermined blood glucose concentration [13].

Clamps: hyperglycaemic clamp

This measurement also involves clamping glucose at a predetermined hyperglycaemic level by intravenously infusing glucose into the blood. Insulin sensitivity is calculated by dividing the glucose infusion rate needed to maintain a hyperglycaemic state by the mean insulin concentration over the last 20 to 30 minutes of the clamp [13].

Insulin infusion sensitivity tests

Insulin infusion testing is similar to clamping methods, but without the intensive blood sampling that is used in the clamping methodology. Somatostatin may also be infused in these tests to suppress endogenous insulin secretion, glucagon, growth hormone, and gluconeogenesis. Glucose, insulin, and somatostatin are infused continuously for 150 to 180 minutes at predetermined constant rates. The steady state plasma glucose, the mean glucose over the last 30 minutes of the test, reflects insulin sensitivity/resistance [13].

Insulin tolerance test

Insulin resistance in this assessment is estimated by the rate of decline in glucose levels following an intravenous bolus of insulin. Blood samples are taken every 2 minutes for 15 minutes and reflect the suppression of hepatic glucose output and stimulation of peripheral glucose uptake. The rate, expressed as a percentage decline in glucose per minute, is calculated by the rate of decline of the log transformed glucose concentrations by linear regression. This calculation reflects insulin sensitivity [13].

Oral glucose tolerance test

OGTT assesses insulin resistance and secretion by sampling the plasma glucose concentrations typically every 15 to 30 minutes for 2 hours following a 75 g oral glucose load [13]. The individual must be in a fasted state (8 to 14 hours) prior to completing the test. There are several surrogate markers of insulin resistance that can be obtained from an OGTT, such as the Matsuda index, Gutt index, Stumvoll index, Avignon index, and oral glucose sensitivity index [11]. The OGTT has been shown to correlate with the hyperglycaemic clamp as a measure of insulin resistance [14].

Selection of studies

After eliminating duplications the search results were screened by two investigators (KLW, DAH) against the eligibility criteria, and those references that could not be eliminated by title or abstract were retrieved and independently reviewed by two reviewers (KLW, DAH) in an unblinded manner. Disagreements were resolved by discussion or by a third and forth researcher (MKB, NAJ). In cases where journal articles contained insufficient information, attempts were made to contact authors to obtain missing details (KLW, DAH).

Data extraction and calculations

Data relating to participant characteristics (age, sex, body mass index [BMI]), exercise intervention (mode of exercise, exercise frequency, intensity, duration, and intervention duration) and measures of insulin sensitivity were extracted independently by two researchers (KLW, DAH), with disagreements resolved by discussion or by two researchers (MKB, NAJ).

Assessment of methodological quality

Two researchers (KLW, DAH) assessed the methodological quality of the included studies (in a blinded manner) using a modified Downs and Black [15] checklist recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [16]. The tool consists of 27 items rated as 'no, 0; unable to determine, 0; and yes, 1' and includes criteria such as: clear description of the aims, interventions, outcome measurements and participants, representativeness of participant groups, appropriateness of statistical analyses, and correct reporting. The checklist was slightly modified so that the final item (number 27) relating to statistical power was consistent with the scoring used for the other items (i.e., from the original score of 0 to 5 to 'no, 0; unable to determine, 0; and yes, 1'). Additionally, two extra criteria were added to the checklist; these were exercise supervision, and monitoring the adherence of participants during the intervention (Supplementary Table 1).

Analyses

The within trial standardised mean difference, or effect size (ES), and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Between-study variability was examined using the I2 measure of inconsistency. This statistic, expressed as a percentage between 0 to 100, provides a measure of how much of the variability between studies is due to heterogeneity rather than chance. Publication bias was assessed by using Egger's test. Subsequently this resulted in two studies [17,18] being excluded from the analyses due to unrealistic large positive effects.

Meta-analyses

Pooled estimates of the effect of exercise on insulin sensitivity, using ES, were obtained using a random-effects model. Subanalyses were also undertaken to examine the effect of: (1) exercise versus control on insulin sensitivity measured <48 hours after the last exercise bout; (2) exercise versus control on insulin sensitivity measured 48 to 72 hours after the last exercise bout and; and (3) exercise versus control on insulin sensitivity measured >72 hours after the last exercise bout. All analyses were conducted using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 2 (Biostat Inc., Englewood, NJ, USA).

RESULTS

Identification and selection of studies

The original search yielded 27,041 studies. One study was found from the reference lists of the manuscripts retrieved. After removal of duplicates and elimination of papers based on the eligibility criteria, 16 studies remained (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Cohort characteristics

Participant characteristics for included studies are shown in Table 1. Of the studies examined, the majority were conducted in previously inactive T2DM populations, predominantly with male cohorts. When combined, 479 individuals (193 male; 166 female; 120 not reported) participated in the trials. One study exclusively recruited female participants [19], two studies exclusively recruited male participants [20,21], nine studies recruited both males and females [17,18,22,23,24,25,26,27,28], and sex was not reported in four studies [29,30,31,32]. The reported mean age of participants ranged from 45.0 to 69.5 years. Based on BMI classification [33], seven studies had participants who were classified on average as overweight [17,18,21,22,23,24,25], six as obese class I [19,26,27,28,29,30], and two as obese class II [20,32]. There was one study that did not report mean BMI [31].

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

| Author | Subject, n | Male sex, % | Age, yr | BMI | Medication, n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baldi et al. (2003) [20]a | C, 9 PRT, 9 |

100 | C, 50.1±3.9 PRT, 46.5±6.3 |

C, 36.4±9.3 PRT, 34.3±9.6 |

Biguanides, 11 Sulfonylureas, 7 |

| Boudou et al. (2003) [21] | C, 8 AEx, 8 |

100 | C, 47.9±8.4 AEx, 42.9±5.2 |

C, 30.9±5.2 AEx, 28.3±3.9 |

C: Metformin, 4 Metformin and gliclazide or glibenclamide, 1 AEx: Metformin, 2 Metformin and gliclazide or glibenclamide, 4 |

| Cuff et al. (2003) [19]a | C, 9 AEx, 9 AEx+PRT, 10 |

0 | C, 60.0±8.7 AEx, 59.4±5.7 AEx+PRT, 63.4±7.0 |

C, 36.7±6.0 AEx, 32.5±4.2 AEx+PRT, 33.3±4.7 |

Oral hypoglycaemics |

| Dunstan et al. (1997) [17] | C, 12 AEx, 11 F, 12 AEx+F, 14 |

C, 75 AEx, 72.7 F, 83.3 AEx+F, 71.4 |

C, 53.0±7.0 AEx, 52.3±8.3 F, 54.1±8.2 AEx+F, 52.6±7.2 |

C, 29.7±4.3 AEx, 29.1±2.4 F, 29.8±4.4 AEx+F, 29.9±3.0 |

Antidiabetic and antihyperten- sive medication |

| Dunstan et al. (1998) [22]a | C, 10 PRT, 11 |

C, 50 PRT, 72.7 |

C, 51.1±7.0 PRT, 50.3±6.6 |

C, 30.1±3.5 PRT, 28.3±2.7 |

Sulfonylureas, 4 Biguanides, 5 Sulfonylureas+biguanides, 10 |

| Karstoft et al. (2013) [24]a | C, 8 AEx, Continuous, 12 Intermittent, 12 |

C, 62.5 AEx, Continuous, 66.7 Intermittent, 58.3 |

C, 57.1±8.5 AEx, Continuous, 60.8±7.6 Intermittent, 57.5±8.3 |

C, 29.7±5.4 AEx, Continuous, 29.9±5.5 Intermittent, 29.0±4.5 |

Antidiabetic and antihypertensive medication (abstained for 5 days prior to pre-/post-testing) |

| Ligtenberg et al. (1997) [28] | C, 28 AEx, 30 |

C, 35.7 AEx, 33.3 |

C, 61.0±5.0 AEx, 63.0±5.0 |

C, 31.2±3.3 AEx, 30.8±4.0 |

Oral hypoglycaemics and insulin |

| Middlebrooke et al. (2006) [29] |

C, 30 AEx, 22 |

At initial recruitment overall, 54.2 | C, 64.6±6.8 AEx, 61.8±7.7 |

C, 29.9±5.4 AEx, 31.8±4.5 |

Oral hypoglycaemics |

| Mourier et al. (1997) [30]a | C, 11 AEx, 10 |

At initial recruitment overall, 83.3 | C, 46.0±10.0 AEx, 45.0±6.3 |

C, 30.1±5.3 AEx, 30.4±2.5 |

Metformin, 14; Sulfonylurea, 3 |

| Okada et al. (2010) [23] | C, 17 AEx+PRT, 21 |

C, 64.7 AEx, 47.6 |

C, 64.5±5.9 AEx, 61.9±8.6 |

C, 24.5±2.9 AEx, 25.7±3.2 |

Study reported both groups received comparable medical intervention after registration for 3 months |

| Ronnemaa et al. (1986) [31] | C, 12 AEx, 13 |

At recruitment, 66.7 | At recruitment overall, 52.5 (NR) | NR | Sulfonylureas, 18 Metformin+sulfonylureas, 10 |

| Tamura et al. (2005) [18]a | D, 7 AEx+D, 7 |

D, 57.1 AEx+D, 42.8 |

D, 55.0±12.7 AEx+D, 46.3±7.4 |

D, 27.4±8.5 AEx+D, 27.1±7.7 |

D: Sulfonylureas, 3 Metformin+sulfonylureas, 2 α-Glucosidase inhibitor, 2 D+AEx: Sulfonylureas, 3 Metformin+sulfonylureas, 3 α-Glucosidase inhibitor, 1 |

| Tan et al. (2012) [25] | C, 10 AEx+PRT, 15 |

At recruitment: C, 45.5 AEx+PRT, 44.4 |

C, 64.8±6.8 AEx+PRT, 65.9±4.2 |

C, 25.8±2.5 AEx+PRT, 25.2±2.5 |

Oral hypoglycaemics |

| Tessier et al. (2000) [26] | C, 20 AEx+PRT, 19 |

C, 55.0 AEx+PRT, 63.2 |

C, 69.5±5.1 AEx+PRT, 69.3±4.2 |

C, 29.4±3.7 AEx+PRT, 30.7±5.4 |

Glyburide: C, 12 AEx+PRT, 10 Metformin: C, 15 AEx, 14 |

| Wing et al. (1988) [32] | Include study 1: P+D, 12 AEx+D, 10 |

At recruitment: Study 1, 16.0 |

Study 1: P+D, 52.5±8.9 AEx+D, 56.2±7.5 |

Study 1: D+P, 37.2±1.8 AEx+D, 39.5±1.9 |

Study 1: P+D, oral hypogylcaemics, 6 AEx+D, oral hypoglycaemics, 6 |

| Winnick et al. (2008) [27] | D, 9 AEx+D, 9 |

D, 33.3 AEx+D, 22.2 |

D, 50.9±3.2 AEx+D, 48.4±8.4 |

D, 32.0±5.3 AEx+D, 34.9±3.1 |

At the outset of the study, all participants discontinued diabetic related medication |

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation.

BMI, body mass index; C, control; PRT, progressive resistance training; AEx, aerobic exercise training; F, fish meal; NR, not reported; D, diet; P, placebo.

aConverted from standard error of mean to standard deviation.

Exercise characteristics

Exercise intervention characteristics are displayed in Table 2. Walking was the most common mode of AEx, while exercises with weight machines were most commonly used for PRT. For the AEx training interventions, 10 studies used continuous training [17,18,21,24,27,28,29,30,31,32], two studies used a combination of continuous and HIIT [21,30], and one study compared continuous training with HIIT [24]. AEx training was most commonly performed 3 days per week [17,21,28,29,30] with sessions lasting 25 to 60 minutes for 1 to 26 weeks. Aerobic exercise intensity, expressed as a percentage of maximal heart rate (HRmax), percentage of heart rate reserve, percentage or peak of maximal rate of oxygen consumption, or percentage of peak energy expenditure, ranged from 35% to 95% [2,17,18,19,21,24,25,26,28,29,31]. PRT was combined with AEx training in five studies [19,22,23,25,26], whilst PRT was performed alone in two studies [20,22]. PRT was most commonly performed 3 days per week, involving two sets per exercise for eight to 12 repetitions, for 10 to 24 weeks. The intensity of PRT, quantified as a percentage of one-repetition maximum (1 RM) in three studies, ranged between 50% to 70% 1 RM [22,25,26]. One study prescribed intensity as 10 to 15 of RM [20].

Table 2. Exercise intervention details.

| Author | Mode | Nutritional intervention | Frequency | Intensity | Session duration | Intervention duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baldi et al. (2003) [20]a | C: non exercising control PRT: circuit targeting major muscle groups of the upper and lower body |

Nil | C: NA PRT: 3/7 (supervised) |

C: NA PRT: 10 RM upper body, 15 RM lower body exercises |

C: NA PRT: progressing from one to three sessions/week; multiple sets of 12 reps for 10 exercises (60 seconds recovery between sets) |

10 weeks |

| Boudou et al. (2003) [21] | C: sham intervention (cycle ergometer) AEx (continuous and HIIT): NR |

Nil | C: 1/7 (supervised) AEx: 2/7+1/7, respectively (supervised) |

C: 30 W (60 rpm) AEx: Continuous: 75% VO2peak HIIT: 50%–85% VO2peak |

C: 20 minutes AEx: Continuous: 45 minutes HIIT: 5×2 minutes at 85% VO2peak, 3 minutes at 50% VO2peak between exercises |

8 weeks |

| Cuff et al. (2003) [19]a | C: usual care AEx (continuous): treadmill, stationary cycle ergometers, recumbent steppers, elliptical trainers, and rower ergometer AEx (continuous)+PRT: AEx–treadmills: stationary cycle ergometers, recumbent steppers, elliptical trainers, rowing machines |

Nil | C: usual care AEx: 3/7 (supervised) AEx+PRT: 3/7 (supervised) |

C: NA AEx: 60%–75% HRR AEx+PRT: AEx: 60%–75% HRR PRT: 2×12 reps |

C: NA AEx: 75 minutes AEx+PRT: 75 minutes |

16 weeks |

| AEx–PRT: stack weight equipment: leg press, leg curl, hip extension, chest press, and latissimus pulldown | ||||||

| Dunstan et al. (1997) [17] | C: sham exercise (cycle ergometer and stretches) AEx (continuous): cycle ergometer F: sham exercise. Cycle ergometer and stretches AEx (continuous)+F: cycle ergometer |

All participants were advised to reduce their sodium intake <100 mmol/day Fish intake groups were instructed to include one fish meal per day |

C: 3/7 (supervised) AEx: 3/7 (supervised) F: 3/7 (supervised) AEx+F: 3/7 (supervised) |

C: Nil AEx: Week 1: 50%–55% VO2peak Week 2–8: 55%–65% VO2peak F: no workload AEx+F: Week 1: 50%–55% VO2peak Week 2–8: 55%–65% VO2peak |

C: 10 minutes cycling; 30 minutes of stretching AEx: 40 minutes F: 10 minutes cycling; 30 minutes of stretching AEx+F: 40 minutes |

8 weeks |

| Dunstan et al. (1998) [22]a | C: non-exercising PRT: circuit including leg extension, bench press, leg curl, bicep curls, overhead press, seated row, forearm extension, and abdominal curls |

Nil | C: NA PRT: 3/7 (supervision NR) |

C: NA PRT: 50%–55% 1 RM |

C: NA PRT: 60 minutes |

8 weeks |

| Karstoft et al. (2013) [24]a | C: NR AEx: Continuous: walking Intermittent: walking |

Nil | C: NA AEx: Continuous: 5/7 (unsupervised) Intermittent: 5/7 (unsupervised) |

C: NA AEx: Continuous: 55% of peak energy-expenditure rate Intermittent: 55%–70% of peak energy-expenditure rate |

C: NA AEx: Continuous: 60 minutes Intermittent: 60 minutes (3 minutes at 70% followed by 3 minutes at 55% of peak energy-expenditure rate) |

4 months |

| Ligtenberg et al. (1997) [28] | C: education program AEx (continuous): Phase 1: cycle ergometer, swimming, treadmill, and rower ergometer Phase 2: exercise at home based on personalised training advice (with contact from investigators) Phase 3: exercise at home without contact from investigators |

Nil | C: NR AEx: Phase 1: 3/7 supervised for 6 weeks Phase 2: phone calls 1/14 for 6 weeks. NR frequency of exercise Phase 3: NR |

C: NR AEx: Phase 1: 60%–80% VO2peak Phase 2: NR Phase 3: NR |

C: NR AEx: Phase 1: 60 minutes Phase 2: NR Phase 3: NR |

26 weeks |

| Middlebrooke et al. (2006) [29] |

C: standard care AEx (continuous): NR |

Nil | C: NA AEx: 3/7 (2/7 supervised; 1/7 unsupervised) |

C: NA AEx: 70%–80% HRmax |

C: NA AEx: 50–60 minutes |

6 months |

| Mourier et al. (1997) [30]a | C: NR AEx (continuous and HIIT): cycle ergometer |

Branched chain amino acid supplementation (46% leucine, 24% isoleucine, 30% valine) Supplementation did not effect metabolic parameters |

C: NA AEx: 2/7 continuous+1/7 HIIT |

C: NA AEx: Continuous: 75% VO2peak HIIT: 50%–85% VO2peak |

C: NA AEx: 55 minutes HIIT: Continuous: 35 minutes (52 minutes at 85%) HIIT: VO2peak followed by 2 minutes at 50% VO2peak |

8 weeks |

| Okada et al. (2010) [23] | C: NR AEx (continuous)+PRT: AEx: aerobic dance, and stationary cycle ergometer PRT: NR |

Nil | C: NA AEx+PRT: 3–5/7 (supervised) |

C: NA AEx+PRT: NR |

C: NA AEx+PRT: AEx: 55 minutes PRT: 20 minutes Overall: 75 minutes |

3 months |

| Ronnemaa et al. (1986) [31] | C: NA AEx: walking, jogging, or skiing |

Nil | C: NA AEx: 5–7/7 |

C: NA AEx: 70% VO2peak |

C: NA AEx: 45 minutes |

4 months |

| Tamura et al. (2005) [18]a | D: Nil AEx (continuous)+D: walking |

Total mean energy intake of 27.9 kcal/kg of ideal body weight for both groups for 2 weeks | D: NA AEx+D: 2–3/7 (unsupervised) |

D: NA AEx+D: 50%–60% VO2peak |

D: NA AEx+D: 30 minutes per session |

2 weeks |

| Tan et al. (2012) [25] | C: maintain individual habits of physical activity AEx (continuous)+PRT: AEx: walking, running PRT: knee flexion, knee extension, hip abduction, hip adduction, and standing calf raise |

Nil | C: NA AEx+PRT: 3/7 (supervised) |

C: NA AEx+PRT: AEx: 55%–70% HRmax PRT: 50%–70% 1 RM |

C: NA AEx+PRT: 60 minutes |

6 months |

| Tessier et al. (2000) [26] | C: NR AEx (continuous) +PRT: AEx: walking PRT: strength/endurance training of major muscle groups |

Nil | C: NA AEx+PRT: 3/7 (supervised) |

C: NA AEx+PRT: Initially: 35%–59% HRmax Week 4 onwards: 60%–79% HRmax |

C: NA AEx+PRT: 60 minutes |

16 weeks |

| Wing et al. (1988) [32] | P+D: sham exercise (light calisthenics and flexibility exercises) AEx+D: walking |

Diet was designed to produce approximately 1 kg/week weight loss | P+D: 2/7 (unsupervised) AEx+D: 2/7 (unsupervised) |

P+D: low intensity AEx+D: moderate intensity (speed and distance increased until the individual able to walk 3 miles) |

~60 minutes | 10 weeks |

| Winnick et al. (2008) [27] | D: NA AEx (continuous)+D: treadmill walking |

Diet designed to maintain body weight close to baseline body weight | D: NA AEx+D: 7/7 |

D: NA AEx+D: Days 1–3, 5–7: 70% VO2peak Day 4: 60% predicted HRmax |

D: NA AEx+D: 2×25 minutes, 10 minutes break between bouts Day 4: 60 minutes |

1 week |

C, control; PRT, progressive resistance training; NA, not applicable; RM, repetition maximum; HIIT, high intensity interval training; NR, not reported; AEx, aerobic training; VO2peak, peak oxygen consumption; HRR, heart rate reserve; F, fish meal; D, diet; HRmax, maximal heart rate; P, placebo.

aConverted from standard error of mean to standard deviation.

Four studies included a dietary or supplement intervention in conjunction with exercise and control [17,18,30,32]. Omega 3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation as fish meal was implemented in one of the studies [17], and branched chain amino acid supplementation in another study [30]. Two studies used diet interventions aimed at energy restriction of either 27.9 kcal/kg of ideal body weight [18] or body weight reduction (1 kg/week) [32]. In all of these studies, the same dietary intervention was given to both exercise and control groups.

Methodological quality

All included studies specified their hypotheses, main outcomes, participant characteristics, interventions, main findings, variability estimates, representative participants, statistical tests, and accuracy of measures (Supplementary Table 1). The majority of studies provided supervision for the intervention groups [17,19,20,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,32] and reported adherence to exercise training during the intervention [17,19,20,22,23,25,26,27,28,29,30,32]. There were eight studies that did not report adverse events during the intervention [18,19,21,22,24,26,31,32], five studies did not report participants lost to follow-up [18,19,20,21,32], and 10 studies did not report P values from statistical analysis [18,19,20,23,25,26,27,28,30,32]. The total score for methodological quality ranged from 16 to 24, out of a possible 29 points, indicating generally moderate study quality.

Study outcomes (ineligible for meta-analysis)

Table 3 shows the extracted outcome measures of all studies included. Two studies were excluded from the meta-analyses due to publication bias, as identified via visual inspection of funnel plot analyses and Egger's test [17,18] (Y intercept, –5.287; standard error [SE], 0.895; 95% CI, –7.166 to –3.407; P<0.000). Upon exclusion, publication bias was improved (Y intercept, –2.942; SE, 0.816; 95% CI, –4.692 to –1.192; P=0.003). Three studies were excluded from the time effect subgroup analyses because they did not report timing of data collection postintervention [23,26,31]. These studies found regular exercise therapy to have a positive effect on glucose uptake as measured by clamp [23] and OGTT [26,31] (Okada et al. [23]: pre, 11.1±5.3 mmol/L, post, 9.7±4.2 mmol/L; Ronnemaa et al. [31]: pre, 19.7±4.9 mmol/L, post, 16.5±7.6 mmol/L; Tessier et al. [26]: pre, 16.6±3.8, post, 15.3±3.1 area under the curve). Only one of these studies was found to have a statistically significant effect (P=0.04) [23].

Table 3. Outcomes of intervention studies for change in insulin sensitivity.

| Author | Mode, n | Measure | Time post-intervention, hr | Pre, mean±SD | Post, mean±SD | Change score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baldi et al. (2003) [20]a | C, 9 PRT, 9 |

OGTT | 36–48 | 2-Hour glucose (mmol/L): C, 16.3±2.7 PRT, 17.0±3.0 |

2-Hour glucose (mmol/L): C, 17.1±2.4 PRT, 16.3±2.1 |

NR |

| Boudou et al. (2003) [21] | C, 8 AEx, 8 |

ITT | 72–120 | Constant rate of glucose disappearance (%/min): C, 1.95±1.00 AEx, 2.15±0.65 |

Constant rate of glucose disappearance (%/min): C, 1.80±0.90 AEx, 3.25±0.85 |

NR |

| Cuff et al. (2003) [19]a | C, 9 AEx, 9 AEx+PRT, 10 |

Clamp | 48–72 | Glucose infusion rate (mg · kg–1 · min–1): C, 2.29±1.38 AEx, 2.78±1.47 AEx+PRT, 2.36±1.04 |

Glucose infusion rate (mg · kg–1 · min–1): C, NR AEx, NR AEx+PRT, NR |

Glucose infusion rate (mg · kg–1 · min–1): C, 0.07±0.84 AEx, 0.55±1.08 AEx+PRT, 1.82±1.64 |

| Dunstan et al. (1997) [17]b | C, 12 AEx, 11 F, 12 AEx+F, 14 |

OGTT | >48 | AUC glucose (mmol/L–1·120 min–1): C, 1,810±340 AEx, 1,916±480 F, 1,787±465 AEx+F, 2,004±500 |

NR | AUC glucose (mmol/L–1·120 min–1): C, 50±48.5 AEx, –112.5±65.0 F, 87.5±87.5 F+AEx, –87.5±75.0 |

| Dunstan et al. (1998) [22]a | C, 10 PRT, 11 |

OGTT | >48 | NR | NR | AUC glucose (mmol/L–1 · 120 min–1): C, 191±265 PRT, –22±205 |

| Karstoft et al. (2013) [24]a | C, 8 AEx: Continuous, 12 Intermittent, 12 |

OGTT | ≈96 | 2-Hour glucose (mmol/L): C, 14.7±3.96 AEx: Continuous, 14.8±3.46 Intermittent, 16.5±3.12 |

2-Hour glucose (mmol/L): C, 15.7±3.96 AEx: Continuous, 15.0±4.85 Intermittent, 15.4±4.50 |

NR |

| Ligtenberg et al. (1997) [28] | C, 28 AEx, 30 |

ITT | <72 | Glucose decline between 4–14 minutes (%·min-1): C, 1.5±1 AEx, 1.8±1.3 |

Glucose decline between 4–14 minutes (%·min-1): C, 1.8±1.1 AEx, 1.8±1.2 |

NR |

| Middlebrooke et al. (2006) [29] | C, 30 AEx, 22 |

ITT | ≥24 | ITT slope (mmol/L–1 · min–1): C, –0.17±0.06 AEx, –0.16±0.10 |

ITT slope (mmol/L–1 · min–1): C, –0.17±0.06 AEx, –0.17±0.07 |

NR |

| Mourier et al. (1997) [30]a | C, 11 AEx, 10 |

ITT | 72–120 | Constant rate of glucose disappearance (%·min-1): C, 1.86±0.96 AEx, 2.28±0.73 |

Constant rate of glucose disappearance (%·min-1): C, 1.81±0.90 AEx, 3.34±0.95 |

NR |

| Okada et al. (2010) [23] | C, 17 AEx+PRT, 21 |

SSPG | NR | SSPG (mmol/L): C, 14.1±3.4 AEx+PRT, 11.1±5.3 |

SSPG (mmol/L): C, 9.7±4.6 AEx+PRT: 9.7±4.2 |

NR |

| Ronnemaa et al. (1986) [31] | C, 12 AEx, 13 |

OGTT | NR | 2-Hour glucose (mmol/L): C, 19.6±4.1 AEx, 19.7±4.9 |

2-Hour glucose (mmol/L): C, 19.7±2.7 AEx, 16.5±7.6 |

NR |

| Tamura et al. (2005) [18]a | D, 7 AEx+D, 7 |

Clamp | >24 | Steady-state glucose infusion rate (mg/kg/min): D, 6.12±2.46 AEx+D, 5.26±0.87 |

Steady-state glucose infusion rate (mg/kg/min): C, 6.49±0.87 AEx+D, 8.22±1.24 |

NR |

| Tan et al. (2012) [25] | C, 10 AEx+PRT, 15 |

OGTT | 72 | 2-Hour glucose (mmol/L): C, 11.11±5.26 AEx+PRT, 13.9±5.8 |

2-Hour glucose (mmol/L): C, 10.58±4.41 AEx+PRT, 9.83±4.33 |

NR |

| Tessier et al. (2000) [26] | C, 20 AEx+PRT, 19 |

OGTT | NR | AUC glucose (mmol/L): C, 16.1±2.9 AEx+PRT, 16.6±3.8 |

AUC glucose (mmol/L): C, 15.9±3.0 AEx+PRT, 15.3±3.1 |

NR |

| Wing et al. (1988) [32] | P+D, 12 AEx+D, 10 |

OGTT | 72 | Plasma glucose: 60 minutes (mmol/L): P+D, 14.6±0.9 AEx+D, 14.3±1.2 |

Plasma glucose: 60 minutes (mmol/L): P+D, 11.3±1.2 AEx+D, 10.9±1.3 |

NR |

| Winnick et al. (2008) [27] | D, 9 AEx+D, 9 |

Clamp | <24 | Glucose levels (mg/dL): D: 137.0±3.0 (low-dose); 135.0±3.0 (high-dose) AEx+D: 131.0±3.0 (low-dose); 123.0±3.0 (high-dose) |

Glucose levels (mg/dL): D: 131.0±3.0 (low-dose); 119.0±3.0 (high-dose) AEx+D: 129.0±3.0 (low-dose); 124.0±3.0 (high-dose) |

NR |

SD, standard deviation; C, control; PRT, progressive resistance training; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; NR, not reported; AEx, aerobic training; ITT, insulin tolerance test; F, fish meal; AUC, area under the curve; SSPG, steady state plasma glucose; D, diet; P, placebo.

aConverted from standard error of mean to standard deviation, bData has been extrapolated from a graph.

Study outcomes (meta-analyses)

The meta-analysis was conducted with 14 studies involving a total of 411 adult participants. For the time effect subgroup analyses, nine studies reported the time of data collection from the last exercise bout. This included three studies which assessed insulin sensitivity less than 48 hours after the last exercise bout [20,27,29], three studies which assessed insulin sensitivity between 48 and 72 hours after exercise [19,25,32], and three studies which assessed insulin sensitivity more than 72 hours after the last exercise bout [21,24,30]. All eligible studies had sufficient data for calculation of ES and 95% CIs for the purpose of meta-analysis.

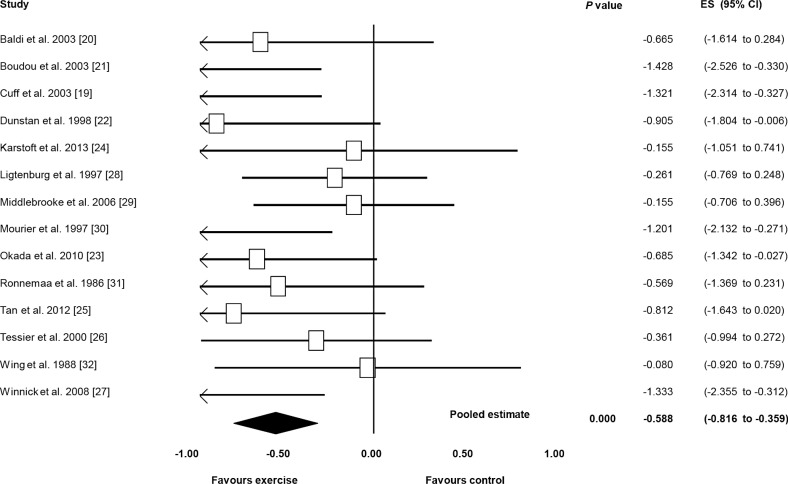

Pooled analysis: exercise versus control

For the effect of exercise on insulin sensitivity, all 14 studies showed an ES favouring exercise therapy, ranging from –0.080 to –1.428. Seven of these studies reached statistical significance for a benefit of exercise versus control [19,21,22,23,27,30,32]. There was a significant pooled ES for the effect of exercise on insulin sensitivity via random effects model (ES, –0.588; 95% CI, –0.816 to –0.359; P<0.000) (Fig. 1). Low (non-significant) heterogeneity among studies was observed (I2= 16.723%, P=0.271).

Fig. 1. Exercise versus control on insulin sensitivity. ES, effect size; CI, confidence interval.

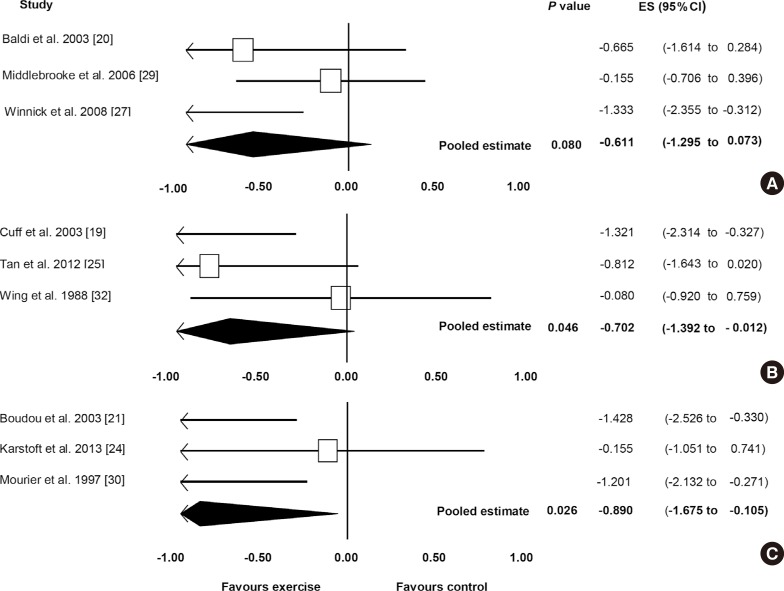

Subanalysis: exercise versus control (<48 hours)

Fig. 2A shows the pooled ES for studies for the effect of exercise on insulin sensitivity for <48 hours after the last exercise bout for the comparison of exercise and control. All three studies [20,27,29] showed an ES favouring exercise therapy, ranging from –1.333 to –0.155. One of these studies reached statistical significance of a benefit of exercise therapy (P=0.011) [27]. The pooled ES showed an improvement in insulin sensitivity in favour of exercise therapy (ES, –0.611; 95% CI, –1.295 to 0.073), although this did not reach statistical significance (P=0.080). Low (non-significant) heterogeneity among studies was observed (I2=39.735%, P=0.103).

Fig. 2. The effect of exercise on insulin sensitivity (A) <48 hours, (B) 48 to 72 hours, and (C) >72 hours after the last bout of exercise. ES, effect size; CI, confidence interval.

Subanalysis: exercise versus control (48 to 72 hours)

Fig. 2B shows the pooled ES for the effect of exercise on insulin sensitivity measured between 48 and 72 hours after the last exercise bout, for the comparison between exercise and control. There was a significant effect favouring exercise versus control (ES, –0.702; 95% CI, –1.392 to –0.012; P=0.046). All three studies [19,25,32] showed an ES favouring exercise therapy, ranging from –1.321 to –0.080, with one of the studies showing a statistically significant improvement with exercise therapy [19]. Low (non-significant) heterogeneity among studies was observed (I2=45.258%, P=0.161).

Subanalysis: exercise versus control (>72 hours)

Fig. 2C displays the pooled ES for effect of exercise on insulin sensitivity measured more than 72 hours after the last exercise bout. A significant effect was observed favouring exercise therapy (ES, –0.890; 95% CI, –1.675 to –0.105; P=0.026). All three studies [21,24,30] showed an ES favouring exercise therapy, ranging from –1.428 to –0.155. Two of the analysed studies reached statistical significance for the benefit of exercise on insulin sensitivity [21,30]. Low (non-significant) heterogeneity among studies was observed (I2=49.0578%, P=0.140).

DISCUSSION

Insulin resistance contributes significantly to the pathophysiology of T2DM and increases the risk of heart disease and cancer. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review with meta-analyses to examine the effect of regular exercise training on dynamic measures of insulin sensitivity in adults with T2DM. The results suggest that, when compared with a control intervention, regular exercise improves insulin sensitivity in T2DM, and this may persist for more than 72 hours after the last exercise bout.

It is generally accepted that regular exercise improves blood glucose control and enhances insulin sensitivity. A previous review and meta-analysis found that structured exercise training had a positive effect on HbA1c levels in adults with T2DM [3], when compared with control. As reported by Umpierre et al. [3], individuals who exercised ≥150 minutes per week showed a significant reduction in HbA1c (–0.89%) compared with those who participated in less than 150 minutes. Another systematic review and meta-analysis which investigated the effect of short-term exercise training (≤2 weeks) on glycaemic control, as measured with continuous glucose monitoring in T2DM, showed that exercise significantly reduced the daily time spent in hyperglycaemia (>10.0 mmol/L), but did not significantly change fasting blood glucose levels [34]. Statistical analysis of longer-term interventions could not be undertaken in this study due to the heterogeneity in the timing of the continuous glucose monitoring measures. Thus whilst regular exercise improves HbA1c and appears to reduce hyperglycaemic incidence, this evidence is based on static measures of glycaemic control and not insulin sensitivity per se. HbA1c is predominately used as a tool for assessing long-term glycaemic control and is considered a representation of fasting and postprandial glycaemia. Fasting glucose and insulin measures are more representative of glycaemic control and basal hyperinsulinemia; however, they do not necessarily reflect glycaemic response to insulin (insulin sensitivity/resistance).

Insulin resistance is marked by a decreased responsiveness to metabolic actions of insulin such as insulin-stimulated glucose disposal and inhibition of hepatic glucose output [35]. Dynamic measures of insulin sensitivity mimic stimulated insulin action, and reflect the peripheral insulin-mediated glucose uptake, making these more sensitive measures than static techniques. Due to the major role of insulin resistance in T2DM, it is therefore important that dynamic measures are considered as assessment strategies to assess the efficacy of interventions [35]. Our study highlights that currently there is a relative lack of evidence from exercise training interventions that have used outcome measures that are valid indices of insulin sensitivity.

Exercise is one of the first management strategies suggested by health professionals for glycaemic control in individuals with T2DM. The American College of Sports Medicine and American Diabetes Association joint position statement [1], and the American Heart Association [2] exercise guidelines recommend that individuals with T2DM should undertake exercise no less than every 48 hours to manage blood glucose levels and insulin resistance [1,2,7], and it has been suggested that the insulin sensitizing effect of exercise may be lost after 48 to 72 hours [36,37]. However, it is generally acknowledged that the improvements seen in insulin sensitivity are not just attributable to acute exercise benefits (repeated regularly via training), but also chronic physiological changes (adaptations) in glucose/insulin metabolism [6]. Namely, an acute bout of exercise has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity in both diabetic [37] and healthy [6,36,37] cohorts, but this effect is transient and diminishes during subsequent days without training [6,36,37]. Yet, cross-sectional data show that endurance athletes; for instance, have a higher insulin responsiveness and greater peripheral glucose uptake than untrained healthy individuals even when the "last bout effect" is removed [38,39]. Similarly, our results from the limited available data provide support for this at the whole body level by showing that regular exercise enhances insulin sensitivity in individuals with T2DM and the magnitude is greater than pre-training levels irrespective of whether there is a short (<48 hours) or longer (>72 hours) period of interspersed inactivity. From a clinical perspective, this may imply that with adherence to chronic/regular exercise training, improved insulin sensitivity can be maintained in people receiving exercise for T2DM management, despite periods of inactivity.

Despite the general consensus that regular exercise is effective for the management of insulin resistance in T2DM, our review highlights a relative lack of data available from high quality studies (14 studies for the pooled analysis in our study) to support this. It does however provide phenotypic support that chronic regular exercise does have a persisting effect that appears to be diminished with acute exercise alone. It is still unclear what dosage and types of exercise result in persisting insulin sensitivity because different exercise modalities, intensities, and durations were used in the eligible studies. Only nine studies reported the time point that insulin sensitivity measures were collected post-intervention. Of these nine studies, only three studies were eligible to be grouped into each time-point subanalyses. While this provides some evidence that chronic exercise has a persisting effect on insulin sensitivity, it is clear that future research needs to investigate this lasting effect. In the time-point subanalyses, only one study implemented PRT [20] and one study used combined exercise therapy (AEx and PRT) [25]. The American College of Sports Medicine and American Diabetes Association joint position statement [1] and the American Heart Association [2] exercise guidelines recommend that individuals with T2DM should partake in combined exercise therapy to manage blood glucose levels and insulin resistance. However, it is clear from our analyses that there is a lack of data available concerning the effect of combined exercise therapy on insulin sensitivity. It is important to note that the eligible studies adhered to the current exercise guidelines (mode, frequency, duration, and intensity) for T2DM glycaemic control [1,2]. Our study reinforces the importance of regular exercise, as suggested by the current exercise guidelines, and its enhancement of insulin sensitivity. The exercise-induced increase in insulin sensitivity is believed to reflect adaptations in muscle insulin signaling [40,41], GLUT4 protein expression, content and action [6,7] and associated improvement in insulin-stimulated glucose disposal and glycogen synthesis [40,41]. This is accompanied and influenced by enhanced intramyocellular oxidative enzyme capacity and possibly changes in muscle architecture from fast-type to slow-type fibres [42,43]. Our analysis supports evidence showing that regular exercise training can produce persistent physiological adaptations that improve insulin sensitivity, which may not just be as a result of transient physiologic responses.

There are some limitations of the current study that should be considered when interpreting the results. Only nine studies met the inclusion criteria and were eligible for the conducted subanalyses, and these were limited by small sample sizes [19,20,21,24,25,27,29,30,32]. Given the potential efficacy of exercise and the generally positive findings of existing studies, there is a clear need for further research examining the effectiveness of exercise interventions on insulin sensitivity, using dynamic measurements. Furthermore, differences in exercise prescription (intensity, duration, frequency, and intervention length) contributed to heterogeneity in the available research. Similarly, the differences in dynamic measurement techniques could further contribute to heterogeneity (clamp, OGTT, and ITT). Evaluating the quality of studies using the Down and Black scale found all of the analyzed studies to be of moderate quality. This may have also contributed to the heterogeneity of the results. There has been a limited investigation of the effect of interval aerobic exercise training on insulin sensitivity in T2DM, despite its known benefit in improving glucose uptake in healthy populations. Further research needs to be conducted to investigate optimal exercise prescription and the treatment of insulin sensitivity in T2DM.

This systematic review with meta-analyses provides useful information for the clinical application of exercise in the management of T2DM. The results show clear evidence for the effectiveness of exercise therapy for improving insulin sensitivity for at least 72 hours after the final bout. However, it cannot be determined whether exercise training frequency may be reduced to this extent, or if more frequent training, as performed in the included studies, is required for the insulin sensitizing effect to become apparent. The results have implications for clinicians in regards to advice pertaining to unexpected breaks from exercise training: a trained individual with T2DM may have a 24- to 72-hour gap in between training sessions due to injury, personal or family reasons. Our results indicate that within this time frame the insulin sensitizing effect is not lost; thus, there may be no increased risk of hyperglycemia or need to adjust medication within this period.

CONCLUSIONS

This is the first study to collectively pool data assessing the effect of regular exercise on dynamic measures of insulin sensitivity in people with T2DM. Our study found that regular exercise has a significant benefit on insulin sensitivity, which may persist for 72 hours or longer after the last training bout. While current exercise guidelines for T2DM highlight the importance of avoiding consecutive days of physical inactivity, there is very limited data from high quality RCTs to corroborate this. Our findings suggest that short periods of inactivity (e.g., 72 hours) may not result in a loss of insulin sensitivity, and this may reflect chronic adaptations to the underlying pathophysiology. Therefore, clinicians should reinforce the importance of regular exercise to manage insulin sensitivity as these chronic benefits may ensure that short-term periods of inactivity will not negate the therapeutic effect from generally regular exercise participation. This study also highlights the relative lack of evidence investigating the effect of insulin sensitivity after prolonged physical inactivity (beyond 72 hours) making it difficult to conclude on the lasting insulin sensitizing effect.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Miss Kimberley L. Way is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Miss Way would like to thank her co-authors for their continuous work and contribution in the development of this manuscript.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Supplementary Material

Results of the modified from Downs et al. [15] methodological quality assessment

Search strategy flow diagram.

References

- 1.Colberg SR, Albright AL, Blissmer BJ, Braun B, Chasan-Taber L, Fernhall B, Regensteiner JG, Rubin RR, Sigal RJ American College of Sports Medicine; American Diabetes Association. Exercise and type 2 diabetes: American College of Sports Medicine and the American Diabetes Association: joint position statement. Exercise and type 2 diabetes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42:2282–2303. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181eeb61c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marwick TH, Hordern MD, Miller T, Chyun DA, Bertoni AG, Blumenthal RS, Philippides G, Rocchini A Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Prevention Committee; Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Exercise training for type 2 diabetes mellitus: impact on cardiovascular risk: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2009;119:3244–3262. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Umpierre D, Ribeiro PA, Kramer CK, Leitao CB, Zucatti AT, Azevedo MJ, Gross JL, Ribeiro JP, Schaan BD. Physical activity advice only or structured exercise training and association with HbA1c levels in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;305:1790–1799. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonora E, Formentini G, Calcaterra F, Lombardi S, Marini F, Zenari L, Saggiani F, Poli M, Perbellini S, Raffaelli A, Cacciatori V, Santi L, Targher G, Bonadonna R, Muggeo M. HOMA-estimated insulin resistance is an independent predictor of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetic subjects: prospective data from the Verona Diabetes Complications Study. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1135–1141. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.7.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Facchini FS, Hua N, Abbasi F, Reaven GM. Insulin resistance as a predictor of age-related diseases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:3574–3578. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.8.7763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borghouts LB, Keizer HA. Exercise and insulin sensitivity: a review. Int J Sports Med. 2000;21:1–12. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-8847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richter EA, Hargreaves M. Exercise, GLUT4, and skeletal muscle glucose uptake. Physiol Rev. 2013;93:993–1017. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00038.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kraniou GN, Cameron-Smith D, Hargreaves M. Acute exercise and GLUT4 expression in human skeletal muscle: influence of exercise intensity. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2006;101:934–937. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01489.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Praet SF, van Loon LJ. Optimizing the therapeutic benefits of exercise in type 2 diabetes. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2007;103:1113–1120. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00566.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Gorman DJ, Karlsson HK, McQuaid S, Yousif O, Rahman Y, Gasparro D, Glund S, Chibalin AV, Zierath JR, Nolan JJ. Exercise training increases insulin-stimulated glucose disposal and GLUT4 (SLC2A4) protein content in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2006;49:2983–2992. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0457-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh B, Saxena A. Surrogate markers of insulin resistance: a review. World J Diabetes. 2010;1:36–47. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v1.i2.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conn VS, Koopman RJ, Ruppar TM, Phillips LJ, Mehr DR, Hafdahl AR. Insulin sensitivity following exercise interventions: systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes among healthy adults. J Prim Care Community Health. 2014;5:211–222. doi: 10.1177/2150131913520328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallace TM, Matthews DR. The assessment of insulin resistance in man. Diabet Med. 2002;19:527–534. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nijpels G, van der Wal PS, Bouter LM, Heine RJ. Comparison of three methods for the quantification of beta-cell function and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1994;26:189–195. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(94)90060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52:377–384. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins JP, Green S Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunstan DW, Mori TA, Puddey IB, Beilin LJ, Burke V, Morton AR, Stanton KG. The independent and combined effects of aerobic exercise and dietary fish intake on serum lipids and glycemic control in NIDDM. A randomized controlled study. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:913–921. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.6.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamura Y, Tanaka Y, Sato F, Choi JB, Watada H, Niwa M, Kinoshita J, Ooka A, Kumashiro N, Igarashi Y, Kyogoku S, Maehara T, Kawasumi M, Hirose T, Kawamori R. Effects of diet and exercise on muscle and liver intracellular lipid contents and insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetic patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:3191–3196. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cuff DJ, Meneilly GS, Martin A, Ignaszewski A, Tildesley HD, Frohlich JJ. Effective exercise modality to reduce insulin resistance in women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2977–2982. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.11.2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baldi JC, Snowling N. Resistance training improves glycaemic control in obese type 2 diabetic men. Int J Sports Med. 2003;24:419–423. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-41173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boudou P, Sobngwi E, Mauvais-Jarvis F, Vexiau P, Gautier JF. Absence of exercise-induced variations in adiponectin levels despite decreased abdominal adiposity and improved insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetic men. Eur J Endocrinol. 2003;149:421–424. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1490421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunstan DW, Puddey IB, Beilin LJ, Burke V, Morton AR, Stanton KG. Effects of a short-term circuit weight training program on glycaemic control in NIDDM. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1998;40:53–61. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(98)00027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okada S, Hiuge A, Makino H, Nagumo A, Takaki H, Konishi H, Goto Y, Yoshimasa Y, Miyamoto Y. Effect of exercise intervention on endothelial function and incidence of cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2010;17:828–833. doi: 10.5551/jat.3798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karstoft K, Winding K, Knudsen SH, Nielsen JS, Thomsen C, Pedersen BK, Solomon TP. The effects of free-living interval-walking training on glycemic control, body composition, and physical fitness in type 2 diabetic patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:228–236. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan S, Li W, Wang J. Effects of six months of combined aerobic and resistance training for elderly patients with a long history of type 2 diabetes. J Sports Sci Med. 2012;11:495–501. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tessier D, Menard J, Fulop T, Ardilouze J, Roy M, Dubuc N, Dubois M, Gauthier P. Effects of aerobic physical exercise in the elderly with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2000;31:121–132. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4943(00)00076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winnick JJ, Sherman WM, Habash DL, Stout MB, Failla ML, Belury MA, Schuster DP. Short-term aerobic exercise training in obese humans with type 2 diabetes mellitus improves whole-body insulin sensitivity through gains in peripheral, not hepatic insulin sensitivity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:771–778. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ligtenberg PC, Hoekstra JB, Bol E, Zonderland ML, Erkelens DW. Effects of physical training on metabolic control in elderly type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Clin Sci (Lond) 1997;93:127–135. doi: 10.1042/cs0930127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Middlebrooke AR, Elston LM, Macleod KM, Mawson DM, Ball CI, Shore AC, Tooke JE. Six months of aerobic exercise does not improve microvascular function in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2006;49:2263–2271. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0361-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mourier A, Gautier JF, De Kerviler E, Bigard AX, Villette JM, Garnier JP, Duvallet A, Guezennec CY, Cathelineau G. Mobilization of visceral adipose tissue related to the improvement in insulin sensitivity in response to physical training in NIDDM. Effects of branched-chain amino acid supplements. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:385–391. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.3.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ronnemaa T, Mattila K, Lehtonen A, Kallio V. A controlled randomized study on the effect of long-term physical exercise on the metabolic control in type 2 diabetic patients. Acta Med Scand. 1986;220:219–224. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1986.tb02754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wing RR, Epstein LH, Paternostro-Bayles M, Kriska A, Nowalk MP, Gooding W. Exercise in a behavioural weight control programme for obese patients with type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes. Diabetologia. 1988;31:902–909. doi: 10.1007/BF00265375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seidell JC, Flegal KM. Assessing obesity: classification and epidemiology. Br Med Bull. 1997;53:238–252. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacLeod SF, Terada T, Chahal BS, Boule NG. Exercise lowers postprandial glucose but not fasting glucose in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of studies using continuous glucose monitoring. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2013;29:593–603. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muniyappa R, Lee S, Chen H, Quon MJ. Current approaches for assessing insulin sensitivity and resistance in vivo: advantages, limitations, and appropriate usage. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;294:E15–E26. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00645.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bogardus C, Thuillez P, Ravussin E, Vasquez B, Narimiga M, Azhar S. Effect of muscle glycogen depletion on in vivo insulin action in man. J Clin Invest. 1983;72:1605–1610. doi: 10.1172/JCI111119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Devlin JT, Hirshman M, Horton ED, Horton ES. Enhanced peripheral and splanchnic insulin sensitivity in NIDDM men after single bout of exercise. Diabetes. 1987;36:434–439. doi: 10.2337/diab.36.4.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCoy M, Proietto J, Hargreves M. Effect of detraining on GLUT-4 protein in human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1994;77:1532–1536. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.3.1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mikines KJ, Sonne B, Farrell PA, Tronier B, Galbo H. Effect of training on the dose-response relationship for insulin action in men. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1989;66:695–703. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.66.2.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Christ-Roberts CY, Pratipanawatr T, Pratipanawatr W, Berria R, Belfort R, Kashyap S, Mandarino LJ. Exercise training increases glycogen synthase activity and GLUT4 expression but not insulin signaling in overweight nondiabetic and type 2 diabetic subjects. Metabolism. 2004;53:1233–1242. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holten MK, Zacho M, Gaster M, Juel C, Wojtaszewski JF, Dela F. Strength training increases insulin-mediated glucose uptake, GLUT4 content, and insulin signaling in skeletal muscle in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2004;53:294–305. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holloszy JO, Coyle EF. Adaptations of skeletal muscle to endurance exercise and their metabolic consequences. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1984;56:831–838. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.56.4.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bruce CR, Kriketos AD, Cooney GJ, Hawley JA. Disassociation of muscle triglyceride content and insulin sensitivity after exercise training in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2004;47:23–30. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1265-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Results of the modified from Downs et al. [15] methodological quality assessment

Search strategy flow diagram.