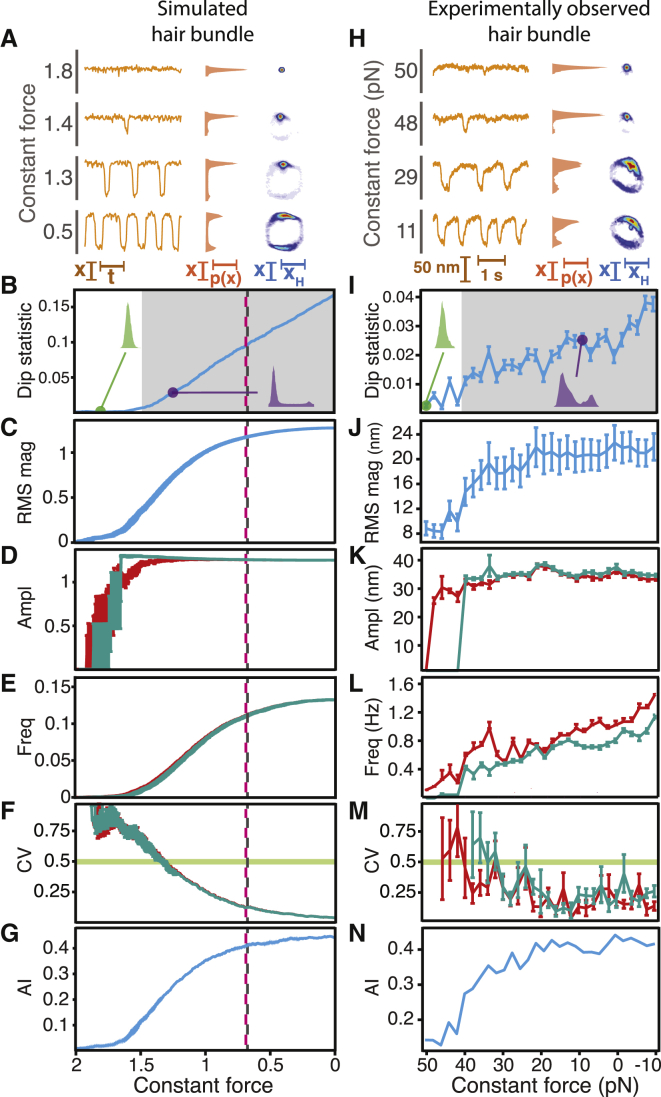

Figure 5.

A subcritical Hopf bifurcation can be crossed by controlling the constant force. When the load stiffness remains low, a decrease in constant force advances a bundle’s operating point across a subcritical Hopf bifurcation. (A–N) Stochastic simulations of a model of hair-bundle motility (A–G) were compared with an experimentally observed hair bundle (H–N). The results depicted here correspond to the same metrics displayed in Figs. 2, 3, and 4. (A) As the constant force decreased, a model bundle exhibited noise-induced spikes of rising frequency (left), an increasingly bimodal position histogram (middle), and an analytic distribution with a cycle whose diameter changed little over a range of forces and upon which rested a locus of higher probability (right). (B) The dip statistic defined an oscillatory boundary at a control parameter smaller than the control parameters corresponding to the deterministic bifurcations (shaded; p < 10−3). (C) The model bundle’s RMS magnitude rose to a nearly constant value as the constant force decreased. (D) Calculated with thresholds of 1 (red) and 2 (cyan), the amplitude of the bundle’s motion remained constant for forces below 1. (E) The frequency of oscillation for a model bundle rose smoothly from zero as the constant force decreased for both peak-detection thresholds. (F) The coefficient of variation remained insensitive to changes in the peak-detection threshold. (G) The analytic information rose with a decrease in constant force. (H) An experimentally observed hair bundle exhibited behaviors that accorded with those of a model bundle crossing a subcritical Hopf bifurcation in the presence of noise. As the constant force declined, the bundle displayed spikes of increasing frequency (left), a more clearly bimodal position histogram (middle), and an analytic distribution with a cycle that changed little in diameter over a range of forces and upon which rested a locus of enhanced probability (right). (I) The dip statistic defined the boundary of the oscillatory region (shaded; p < 10−3). (J) The RMS magnitude of the bundle’s motion rose as the constant force fell below 40–45 pN and achieved a constant value for forces below 35 pN. (K) The amplitude of the bundle’s oscillations achieved a nearly constant value for forces below 35–48 pN. We employed peak-detection thresholds of 50 nm (red) and 60 nm (cyan). (L) The bundle’s frequency of oscillation rose gradually from zero as the constant force decreased. (M) The constant force at which the coefficient of variation exceeded 0.5 remained relatively insensitive to changes in the peak-detection threshold. (N) The analytic information rose as the constant force decreased. For experimental data, the load stiffness was 100 μN·m−1 with a gain of 0.1. The stiffness and drag coefficient of the stimulus fiber were 139 μN⋅m−1 and 239 nN⋅s⋅m−1, respectively. Black dashed lines correspond to the location of the subcritical Hopf bifurcation at FC = 0.66, and pink dashed lines correspond to the location of the saddle-node of limit cycles bifurcation at FC = 0.664 in the absence of noise. Stochastic simulations of the model of hair-bundle motility possessed a stiffness of 2 and noise levels of σx = σf = 0.2. The error bars represent standard errors of the means.