Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Individuals with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders have increased rates of mortality relative to the general population. The relationship between measures of treatment quality and mortality for these individuals is unknown.

OBJECTIVE

To examine the association between 5 quality measures and 12- and 24-month mortality.

DESIGN, SETTING AND PARTICIPANTS

Retrospective cohort study of patients with co-occurring mental illness (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and major depression) and substance use disorders who received care for these disorders paid for by the Veterans Administration between October 2006 and September 2007. Logistic regression models were used to examine the association between 12 and 24-month mortality and 5 patient-level quality measures, while risk-adjusting for patient characteristics. Quality measures included receipt of psychosocial treatment, receipt of psychotherapy, treatment initiation and engagement, and a measure of continuity of care. We also examined the relationship between number of diagnosis-related outpatient visits and mortality, and conducted sensitivity analyses to examine the robustness of our findings to an unobserved confounder.

MAIN OUTCOMES MEASURE

Mortality 12 and 24 months after the end of the observation period.

RESULTS

All measures except for treatment engagement at 24 months were significantly associated with lower mortality at both 12 and 24 months. At 12 months, receiving any psychosocial treatment was associated with a 21% decrease in mortality; psychotherapy, a 22% decrease; treatment initiation, a 15% decrease, treatment engagement, a 31% decrease; and quarterly, diagnosis-related visits a 28% decrease. Increasing numbers of visits were associated with decreasing mortality. Sensitivity analyses indicated that the difference in the prevalence of an unobserved confounder would have to be unrealistically large given the observed data, or there would need to be a large effect of an unobserved confounder, to render these findings non-significant.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

This is the first study to show an association between process–based quality measures and mortality in patients with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders, and provides initial support for the predictive validity of the measures. By devising strategies to improve performance on these measures, health care systems may be able to decrease the mortality of this vulnerable population.

Keywords: co-occurring disorders, quality measures, mortality, quality of care, mental health services, veterans

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Mental and substance use disorders are leading causes of preventable deaths (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014; National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2012; Walker, McGee, & Druss, 2015). Compared to the general population, individuals with mental disorders, substance use disorders and co-occurring mental and substance use disorders have increased mortality rates, with the highest rates found in clinical samples and among individuals with co-occurring psychosis and substance use disorders (Degenhardt, Bucello, et al., 2011; Degenhardt, Singleton, et al., 2011; Dickey, Dembling, Azeni, & Normand, 2004; Mathers et al., 2013; Muhuri & Gfroerer, 2011; Roerecke & Rehm, 2013; Rosen, Kuhn, Greenbaum, & Drescher, 2008; Singleton, Degenhardt, Hall, & Zabransky, 2009; Walker et al., 2015). Reducing the premature mortality associated with mental and substance use disorders is an ongoing public health challenge and an important goal for health care systems. While health care systems have little influence over some causes of premature mortality, such as accidents and homicides, they do have control over the quality of the care they deliver, which may also influence mortality, through earlier recognition of worsening physical health symptoms or by influencing patients’ risk behaviors by providing effective treatment. If health care systems are to play a role in reducing premature deaths among persons with co-occurring disorders, then is important to know whether or not a relationship exists between quality of care and mortality. However, it is unknown whether and how the quality of healthcare impacts mortality for individuals with co-occurring disorders.

Understanding the link between healthcare quality and mortality requires scientifically rigorous and valid measures. Valid measures are also essential for quality improvement efforts. Quality of care is typically measured using either measures of process, which assess what is happening in the healthcare setting, or outcomes, which assess the impact of the care on the patient’s symptoms or functioning. While improved patient outcomes is the gold standard for measuring quality, using outcome-based quality measures is potentially problematic for at least three reasons. Obtaining outcome data can be expensive and difficult to collect; outcome data cannot be used to identify which care processes need to be improved, and outcome measures require risk adjustment for illness severity. Process-based measures, which can be operationalized using readily-available administrative data, are an important source of information about where performance falls short and quality improvement efforts should be targeted. Process-based measures can also be reported in real-time, allowing health care systems to take timely corrective action.

There are no reliable and valid process-based, quality measures that have been developed and tested for individuals with co-occurring disorders (Dausey, Pincus, & Herrell, 2009). Thus, although care for individuals with mental and/or substance use disorders varies across treatment systems (Watkins, Pincus, et al., 2011; Watkins et al., 2015), and settings (Charbonneau et al., 2003; Harris, Bowe, Finney, & Humphreys, 2009; Kilbourne et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2014), differences in the process of care have not been linked to differences in patient outcomes, and there are no process-based quality measures that predict improved outcomes. Thus it is unknown whether improvements in treatment process would lead to improvements in patient outcomes. Existing process-based behavioral health quality measures focus on either mental or substance use disorders and have not been validated in a population with comorbid disorders (Harris, Gupta, et al., 2015). Unless process measures are associated with clinically meaningful outcomes, using them to monitor and improve performance will not result in the expected improvements in outcomes.

Given the importance of mortality as a clinical outcome and the need for validated quality measures applicable to this population, we examined the association of 5 potential quality measures with one- and two-year mortality among persons with co-occurring disorders. If these process-based quality measures are associated with decreased mortality, it suggests health care systems could devise specific strategies to improve performance on these measures and, by doing so, have some assurance that the care they are providing is linked to improvements in this essential patient outcome. It would also provide initial evidence for the predictive validity of the measures.

2. Methods

2.1 Overview

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare Center and the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. The boards waived the requirement for participant informed consent as it was a minimal risk study, using previously collected data. Administrative data was obtained from the Veterans Administration (VA) Medical SAS data sets, and included demographic information, claims, diagnoses, dates and types of services, admissions, and discharges. Mortality through September 30, 2009 was obtained from the VA Vital Status Mini File.

2.2 Study Population

We identified all veterans who received care from or paid for by the VA in FY2007 using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 codes for schizophrenia (295.0–295.9), bipolar I disorder (296.0–296.7), major depression (296.2–296.3), post-traumatic stress disorder (309.81) and substance use disorder (303.9–305.7; 305.9). Veterans were included in the study population if within FY2007 their utilization records contained diagnosis codes for one of the four mental disorders and a substance use disorder, and if they had at least one inpatient episode or two outpatient encounters, one of which was related to a study diagnosis, to show active engagement with VA care.

2.3 Quality Measures

We used a multi-step process developed by Mittman and colleagues (Mittman, Hilborne, & Brook, 1994) to identify the 5 process-based quality measures. We started with a comprehensive literature review and then used the nominal group/Delphi method to abstract discreet treatment recommendations from clinical practice guidelines. The set of recommendations were reviewed by a panel of internal and external technical experts, and iteratively revised and winnowed down until a final set of measures of acceptable face validity and feasibility was produced with all necessary technical specifications (Watkins, Horvitz-Lennon, et al., 2011; Watkins, Smith, et al., 2011). We focused on process measures because they are the most readily available across a range of settings, are easier to collect than outcome measures, and provide actionable information about the types of care associated with improved patient outcomes. Because of the low prevalence of mortality as an outcome, we only examined measures that were applicable across diagnoses to the population of individuals with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders. Receipt of any psychosocial treatment was defined as receiving at least one diagnosis-related psychosocial treatment visit for a mental or substance use disorder in the observation year, including individual and group psychotherapy, family interventions, supported employment, skills training and intensive case management. Receipt of any psychotherapy included only diagnosis-related visits with an associated group or individual psychotherapy current procedural terminology (CPT) code in the observation year. Two of the measures, treatment initiation and treatment engagement, were developed by the Washington Circle for substance use disorders and are Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures (Garnick et al., 2002; National Committee for Quality Assurance, 2013). Both measures apply only to individuals beginning a new treatment episode; new treatment episodes begin with an index visit for a substance use disorder. Treatment initiation was defined as at least one substance use disorder-related treatment visit within 14 days of the index visit, and treatment engagement was defined as receiving an additional two substance use disorder-related treatment visits within 30 days after the initiation visit, among those who had initiated. Unlike the HEDIS specifications, for the index visit we required a period of 5 months rather than 60 days without any substance use disorder-related visits prior to the index visit (Harris, Ellerbe, et al., 2015). We tested an alternative specification for the treatment initiation and engagement measures where we allowed the index visit and the follow-up visits to be for either the mental health or substance use disorder. Since the relationships observed were similar to the original specifications, we present data only from the original specifications, which required that the index and follow up visits be for a substance use disorder. The final measure describes an aspect of continuity of care, continuous care over time (Wierdsma, Mulder, de Vries, & Sytema, 2009), which we defined as receiving at least one diagnosis-related visit (either mental illness or substance use disorder) each quarter over a one-year period from any type of provider. We tested alternative specifications for this measure, including restricting the type of provider to a prescribing provider or a mental health prescribing provider and examining the relationship between number of visits and mortality. Because the relationships observed were similar regardless of the provider type, we present data from the least restrictive version of the measure.

2.4 Covariates

To risk-adjust rates of mortality, we used demographic and clinical variables which were available in the administrative data, including age, gender, racial/ethnic background, marital status, rural/urban location (defined using Rural-Urban Community Area (RUCA) codes (Morrill, Cromartie, & Hart, 1999) and administrative zip code data), and whether the veteran had a service-connected disability for a mental or substance use disorder, because service-connection status is associated with increased illness severity and veterans with a service-connected disability are given priority access to VA services. Given that patients with multiple comorbidities show increased healthcare utilization but worse outcomes, a comorbidity measure based on the Charlson-Deyo comorbidity index (Deyo, Cherkin, & Ciol, 1992; Klabunde, Potosky, Legler, & Warren, 2000) was used to adjust for mortality risk due to physical health conditions found in administrative data. The index was modified by the VA Information Resource Center (VIReC) for use with mixed inpatient and outpatient data and to capture VA outpatient procedures (VA Information Resource Center, 2014).

2.5 Statistical Analyses

We examined descriptive statistics for 12- and 24-month mortality outcomes, patient risk-adjustment characteristics, and for the quality measures. We restricted analyses to the population of study patients who were alive at the end of the observation period for each quality measure in order to unbiasedly estimate mortality following quality measure-specific landmark times (Dafni, 2011). For our primary analyses examining the overall process-outcomes association for each measure and each mortality time point, we fit a logistic regression to model the probability of mortality, including the quality measure and patient risk-adjustment characteristics as independent variables. Observations with missing covariate data (namely marital status and/or rural residence) or mortality rate (approximately 3.6% of the population) were omitted from the outcomes analyses. We assessed the strength of association between a quality measure and mortality by examining the odds ratio of mortality for the quality measure and its 95% confidence interval (CI). We applied the predictive margins approach to the risk-adjusted logistic regression output to estimate the marginal effect on mortality of receipt of care measured by the quality measure, holding constant the risk-adjustment patient characteristics (Graubard & Korn, 1999), and computed the marginal percent reduction in mortality associated with receiving a quality measure. We also report the avoidable excess mortality number which refers to the number of deaths that potentially could have been averted had the patient received the respective quality measure. For a specific quality measure, the avoidable mortality number was calculated as the product of the difference in mortality rates between those who met and did not meet the measure, and the size of the population of patients who did not receive measured care. Standard errors of model coefficients were adjusted for the clustering of observations within one of 139 service areas. Service areas are geographic regions nested within 21 regionally-defined Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs), which are designed to pool and align resources in order to better meet local health care needs and provide greater access to care. Each service area is anchored by either a major VA medical center or a major VA outpatient clinic partnered with a non-VA hospital or medical center. The major VA medical centers are responsible for one or more community-based outpatient clinics and, in a few cases, other VA medical centers or freestanding hospitals.

We performed two secondary analyses. Because the overall association between quality measures and mortality might reflect differences between service areas (Finney, Humphreys, Kivlahan, & Harris, 2011), we also examined the within-service area associations between quality measures and mortality by fitting logistic regression models similar to those described above but adding fixed-effect terms for service areas instead of cluster-adjusting for service areas. The estimated odds ratio for a quality measure for these analyses compares mortality risk by receipt of the quality measure for patients within the same service area. We also conducted a secondary analysis to further explore the association between number of diagnosis-related outpatient visits and mortality at 12 and 24 months. For this analysis, the key independent variable was a categorical measure of the number of visits during the year (1–2 (reference), 5–10, 11–20, 21–50, 51 or more) and included patient risk-adjustment variables. Only patients alive at the end of FY07 were included in this analysis.

2.6 Sensitivity Analysis

A complication to examining the association between receipt of care and mortality using observational data is that the amount and quality of care patients get could differ based on the severity of their illness in a way unexplained by the measured data on patient risk factors (Lin, Psaty, & Kronmal, 1998). We apply a sensitivity analysis approach (Lin et al., 1998) to evaluate how sensitive our results would be to a hypothetical dichotomous unmeasured confounder, U, that were unavailable in the data and had a positive association with mortality. We implement this by assuming the true logistic regression model should contain an additional term, b*Ui, where b is the regression coefficient for Ui, the value of a hypothetical unobserved confounder for patient i. We examine how large an effect U would need to have to invalidate our statistically significant findings. For each quality measure, we examine three scenarios under which U is associated with higher mortality:

The magnitude of the effect of U is the size of the average QM effect across all of the analyses (OR(U)=exp(b3)=1.27)

The magnitude of the effect of U is equal to the maximum QM effect (OR(U) =1.43)

The magnitude of the effect of U exceeds the largest observed effect of the QM and risk-adjustment variables1 across all of the analyses (OR(U) =2.58).

These values of OR(U) were chosen since effects of these magnitudes were found in our analyses, making them plausible estimates of the potential size of an unobserved confounder’s effect (Griffin, McCaffrey, Ramchand, Hunter, & Suttorp, 2012).

3. Results

In FY2007, 144,045 patients with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders accessed services paid for or provided by the Veterans Health Administration. Table 1 shows their demographic and descriptive characteristics; 95% were male and the average age was 52 (SD=10.6). The most common mental health diagnosis was post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), followed by major depression; the most common substance use disorder diagnosis was alcohol abuse or dependence. Seventy-five percent had at least one new treatment episode, for either a mental or substance use disorder or both. The mortality rate was 2.7% at 12 months (3,947 individuals), and ranged from a low of 2.6% for individuals with co-occurring bipolar disorder to a high of 3% for individuals with co-occurring schizophrenia. The mortality rate at 24 months was 5.3% (7,634 individuals), and ranged from 5.1% for individuals with co-occurring PTSD to 5.9% for individuals with co-occurring bipolar disorder.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Veterans with Co-Occurring Mental and Substance Use Disorders Receiving Care from VHA, FY 2007 (N=144,045)

| Male, No. (%) | 136,138 (94.5) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 52.2 (10.6) |

| Race/Ethnicity* | |

| White, No. (%) | 72,049 (50.0) |

| Black, No. (%) | 32,335 (22.5) |

| Hispanic, No. (%) | 5,956 (4.1) |

| Other/Unknown, No. (%) | 33,705 (23.4) |

| Marital Status* | |

| Married, No. (%) | 44,592 (31.0) |

| Not Married, No. (%) | 98,406 (68.3) |

| Patient setting ** | |

| Rural, No. (%) | 28 925 (20.3) |

| Urban, No. (%) | 113 650 (79.7) |

| Service connected, No. (%) | 75,289 (52.3) |

| Mental Health Disorder | |

| Schizophrenia | 20 680 (14.4) |

| Bipolar I Disorder | 19 714 (13.7) |

| PTSD | 73 213 (50.8) |

| Major Depression | 30 438 (21.1) |

| Charlson-Deyo Morbidity Index | 0.43 (1.16) |

| With NTEa, No. (%) | 107,838 (74.9) |

| With SUD NTE, No. (%) | 100,245 (69.6) |

| With MH NTE, No. (%) | 52,294 (36.3) |

| Mortality | |

| 12-month, No. (%) | 3,880 (2.7) |

| 24-month, No. (%) | 7,494 (5.3) |

Does not equal 100% due to missing data

RUCA code missing for 1470 patients

New Treatment Episode

Table 2 shows the measured adherence to the 5 quality measures. Nearly 90% received at least one psychosocial treatment visit and nearly two-thirds received at least one psychotherapy visit. Among those with a new treatment episode, 19.8% initiated treatment, and 60.2% engaged with treatment. Forty-one percent had at least one diagnosis-related outpatient visit in each quarter.

Table 2.

Performance on Quality of Care Measures for Veterans with Co-Occurring MH and SU Disorders

| Measure | Performance, No. (%) | Patients Eligible, No. |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment within 14 days of inpatient/outpatient SUD NTE (treatment initiation) | 19,856 (20) | 100,245 |

| 2 or more visits within 30 days of the initiation visit, among those who initiated (treatment engagement) | 11,956 (60) | 19,856 |

| At least 1 diagnosis-related visit per quarter | 59,322 (41) | 144,045 |

| At least 1 psychosocial visit | 129,106 (90) | 144,045 |

| At least 1 psychotherapy visit | 86,095 (60) | 144,045 |

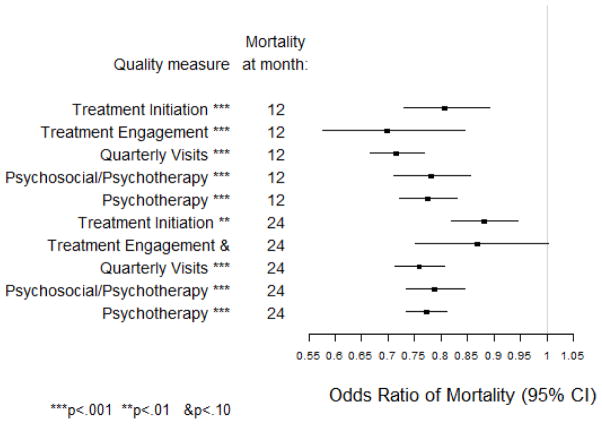

Figure 1 shows the risk-adjusted odds ratio estimates of 12- and 24-month mortality for the quality measures in the primary outcomes analyses, where the odds ratios are represented as squares and their 95% confidence intervals as horizontal segments. All measures except treatment engagement at 24 months (p=0.056) were significantly associated with lower mortality at both 12- and 24-month follow-up time points (p=0.001 for treatment initiation at 12- months; p= 0.005 for treatment initiation at 24-months; p<0.001 for all other measures and follow-up time points). The analogous results for the within-service area estimates of the quality measure association with mortality are essentially identical to those shown in Figure 1 and are omitted.

Figure 1.

Mortality associated with receiving the care assessed by each quality measure at 12 and 24 months

Table 3 translates the model results shown in Figure 1 to predicted probabilities of mortality by receipt of each quality measure, and shows the avoidable excess mortality for each quality measure. Receiving the care described by the quality measure reduced 12-month mortality by 19% to 31%, and 24-month mortality by 9% to 22% across the measures.

Table 3.

12-Month and 24-Month Mortality by Measure Performance; Avoidable Excess Mortality

| Quality Measure | Patients Eligible, No. | Mortality Rate-Received Measured Care (%) | Mortality Rate-Did not Receive Measured Care (%) | % Change | Avoidable Excess Mortality, No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12-Month Mortality | |||||

| Treatment Initiation | 98,291 | 2.1 | 2.6 | −15 | 314.5 |

| Treatment Engagement | 19,541 | 1.9 | 2.7 | −31 | 62.5 |

| Quarterly Provider Visits | 138,930 | 2.3 | 3.1 | −28 | 655.7 |

| Psychosocial Treatment | 138,930 | 2.7 | 3.4 | −21 | 97.3 |

| Psychotherapy Treatment | 138,930 | 2.5 | 3.1 | −22 | 333.4 |

| 24-Month Mortality | |||||

| Treatment Initiation | 98,291 | 4.7 | 5.2 | −9 | 393.2 |

| Treatment Engagement | 19,541 | 4.4 | 5.1 | −14 | 54.7 |

| Quarterly Provider Visits | 138,930 | 4.6 | 5.8 | −22 | 983.6 |

| Psychosocial Treatment | 138,930 | 5.2 | 6.4 | −20 | 166.7 |

| Psychotherapy Treatment | 138,930 | 4.8 | 6.0 | −22 | 666.9 |

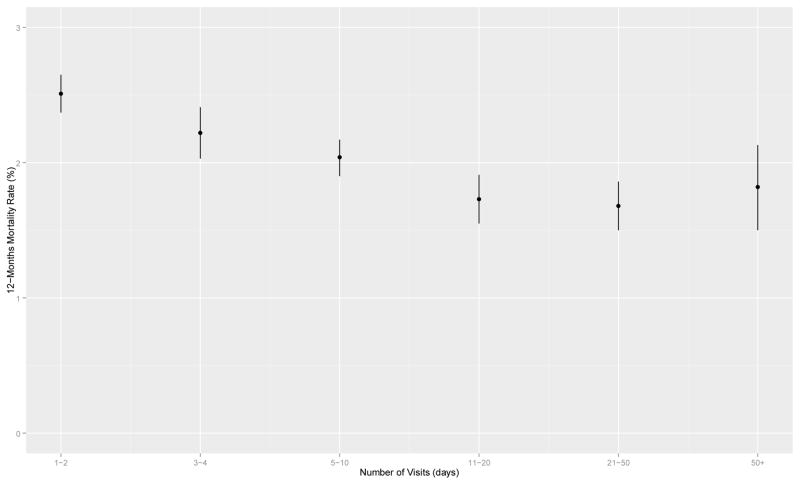

Figure 2 shows the association between the number of diagnosis-related outpatient visits and 12-month mortality. Increasing numbers of outpatient visits is associated with an almost linear decrease in mortality at every category of visits until it levels off with the category of 21–50 visits, and increases slightly among veterans with more than 50 visits.

Figure 2.

Association between number of diagnosis-related visits and 12-month mortality for veterans with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders, FY2007–FY2008

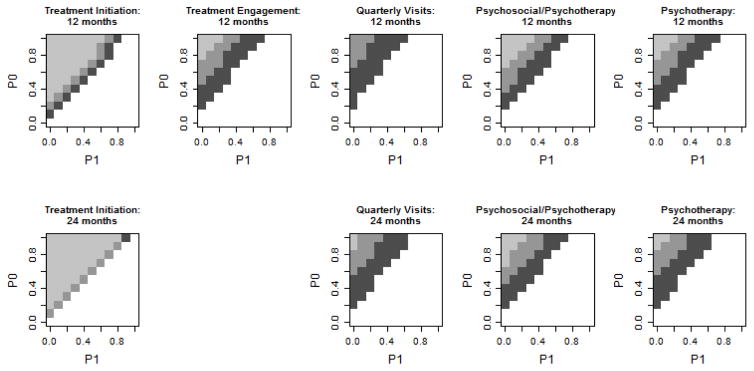

Figure 3 summarizes how large an effect an unobserved confounder would need to have to render the multivariate analysis findings for five quality measures at 12 month and four quality measures at 24 months to be non-significant (Lindenauer et al., 2014). Statistical significance depends on the prevalence of U for those who receive the quality measure (P1: x-axis), the prevalence among those who do not receive the quality measure (P0: y-axis), and the odds ratio of U. Darker shading indicates stronger effects of U are required to render the finding non-significant (p>0.05). Specifically, the dark gray / middle gray / light gray shading indicates combinations of P1 and P0 for which OR(U) = 2.58 / 1.43 / 1.27 would render the findings non-significant. Non-shaded areas represent combinations of P0 and P1 for which the significance of the findings holds for the three values of OR(U) examined here.

Figure 3. Sensitivity analysis of the potential impact of an unobserved confounder, U, on significant associations of the quality measure and mortality.

Areas with no shading remained significant for selected OR(U) values. Shaded areas represent combinations of P1, P0, and OR(U) that would result in a loss of significance of the QM-mortality association. Dark gray: OR(U)=2.58, middle gray: OR(U)=1.43, light gray: OR(U)=1.27.

The results are most sensitive for the treatment initiation quality measure at 24 months. For that analysis, the difference in the proportion having U=1 among those with versus without the quality measure, or P1–P0, would need to differ by 0.1 to render the association non-significant provided OR(U) >= 1.43. A smaller OR(U) of 1.27 would render the quality measure non-significant if the prevalence of U differed by 0.2. Greater amounts of unobserved confounding would be required to render the other measures in Figure 3 non-significant. For example, in the 12-month mortality analysis of the visits measure, P1 and P0 would need to differ by 0.2 and OR(U)=2.58 to render the findings non-significant. To put the relative importance of these hypothetical differences between P1 and P0 into context, we note that when examining the prevalence of our dichotomous observed confounders (e.g., covariates in our regression models) the largest difference observed difference between P1 and P0 across the measures in this study was only 0.15.

4. Discussion

Among patients with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders, better performance on these process-based quality measures was associated with decreased 12- and 24-month mortality. While our analyses do not address the relative effectiveness of different types of care or different types of providers, the consistency of the findings across measures, as well as the sensitivity analyses, suggests there is a robust association between more service utilization and decreased mortality, and provide preliminary evidence that this relationship might not be driven by unmeasured confounders. While we do not know if there is an optimal or minimum level of visit frequency required to achieve this reduction in mortality, our continuity of care measure was endorsed by the expert panel as consistent with good clinical practice and may be a reasonable standard for health care systems. Alternatively, our results show that despite the assumption that sicker patients should receive more treatment, mortality declines are associated with increasing numbers of visits up to the category of 21–50 visits, and suggests a quality measure of 1–2 visits per month should be considered for this population. Our results, also provide evidence that the two-part substance use disorder quality measure endorsed by the National Quality Forum and HEDIS (National Committee for Quality Assurance, 2013) (i.e., treatment initiation and engagement), may be valid for a population with co-occurring disorders.

Although few studies have examined the logical link between utilization and mortality, those that have suggest that more service use could increase the chances of early identification and management of emerging physical health problems, increase receipt of preventive health services, or identify mental health decompensation and relapse at an earlier stage (Bowersox et al., 2012; Copeland et al., 2009; Davis et al., 2012; Druss, Bradford, Rosenheck, Radford, & Krumholz, 2001; Hayes et al., 2015; Rehm & Roerecke, 2013; Roerecke, Gual, & Rehm, 2013; A. Scott & Guo, 2012; Tondo, Albert, & Baldessarini, 2006). Physical health problems are common among individuals with serious mental illness (Newcomer & Hennekens, 2007), with one study suggesting that over 80% had an important medical comorbidity (Batki et al., 2009). Treatment may also result in decreased alcohol and drug use. Among individuals with substance use disorders, decreasing alcohol consumption and increasing abstinence from drugs have both been shown to be associated with reductions in mortality risk (Hser et al., 2006; Langendam, van Brussel, Coutinho, & van Ameijden, 2001; Laramee et al., 2015; Roerecke et al., 2013; C. K. Scott, Dennis, Laudet, Funk, & Simeone, 2011; Shield, Rehm, Rehm, Gmel, & Drummond, 2014). While this study did not examine the mechanism of how better quality is associated with decreased mortality, it is plausible that the same mechanisms that link increased utilization with decreased mortality for individuals with only one disorder are present for individuals with co-occurring disorders. Our findings are also consistent with prior research, which showed that among veterans with schizophrenia or bipolar disorders who dropped out of care for prolonged periods, reengagement and subsequent utilization of VA services was associated with a six-fold decrease in mortality compared to patients who did not return to medical care (Davis et al., 2012). This decrease in mortality was primarily due to a decrease in non-injury mortality from cancer and cardiovascular disease (Bowersox et al., 2012), which lends credibility to the premise that reduction in mortality in our study may be a result of receipt of more physical health or preventive care. Our results are also consistent research that showed that timely follow-up after residential treatment for substance use disorders was associated with decreased two-year mortality (Harris, Gupta, et al., 2015).

The association between utilization and mortality has important clinical implications. Individuals with mental illness die on average 8.2 years earlier than the rest of the population; those with serious mental illness die on average 11–25 years earlier (Colton & Manderscheid, 2006; Druss, Zhao, Von Esenwein, Morrato, & Marcus, 2011; Parks, Svendsen, Singer, & Foti, 2006). Substance use is also associated with premature mortality (Dickey et al., 2004; Roerecke & Rehm, 2013; Rosen et al., 2008; Yoon, Chen, Yi, & Moss, 2011), and the highest premature mortality rates have been found in clinical samples of individuals with co-occurring psychosis and substance use disorders (Dickey, Normand, Weiss, Drake, & Azeni, 2002; Maynard, Cox, Hall, Krupski, & Stark, 2004). Our results suggest that interventions to increase treatment utilization may decrease mortality and suggest ways for health care systems to improve this important outcome. While we are not able to compare the strength of the relationship for different types of utilization, it is notable that for the measure that assessed the most general type of utilization—one visit per quarter to any type of provider—the relationship was observed only when mental illness or substance use was coded as a primary or secondary reason for the visit. This suggests the importance of all providers being alert to the presence of these diagnoses.

While process-based quality measures are receiving increasing support (Bilimoria, 2015), unless process-based measures are reliably associated with clinically important outcomes, using them to drive performance improvement may not lead to improved clinical outcomes. Additionally, the operationalization of the measure must be both feasible and valid (Harris, Reeder, Ellerbe, & Bowe, 2011), and any potential bias due to unmeasured confounding must be assessed (Parast et al., 2015). The proposed quality measures described can be operationalized using administrative data available in many treatment settings, making them feasible to implement and report, and the consistency of the association with mortality across different measures of utilization suggest that the fidelity with which the measure can be operationalized is not a significant issue. The robustness of our main findings is supported by the sensitivity analysis. Either the difference in the prevalence of an unobserved confounder by receipt of the quality measure would have to be unrealistically large given the observed data or a relatively large effect of an unobserved confounder would be required in order to render these findings non-significant.

This study adds to the literature on the relationship between initiation and engagement and other outcomes such as employment, arrest and drug and alcohol use (Dunigan et al., 2014; Garnick et al., 2014; Garnick et al., 2012; Harris, Humphreys, Bowe, Tiet, & Finney, 2010). While those studies did not specifically look at the population of individuals with co-occurring disorders, several of them did control for mental health co-morbidity. Unlike our study, those studies found a significant association with outcomes only for the engagement measure. Since among the five measures, treatment initiation showed the weakest association with mortality, it is possible that the previous studies were limited by sample size and a lack of power.

Strengths of our study include the large, population-based administrative database that is large enough to support examining mortality, given mortality’s low prevalence. Our quality measures should be feasible to use across a variety of systems and settings and apply to the majority of patients with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders. A potential limitation is that we do not know if our results will generalize to care outside of the VA system. However the consistency of the association across measures, and the consistency of findings across different types of visits, suggests that our findings are not tied to a specific type of service or the fidelity with which the care process was delivered. Our observational data analysis can identify associations but not causal mechanisms leading to decreased mortality. Though our sensitivity analysis establishes the robustness of our associations for a plausible range of unobserved confounding, results could be sensitive to other types of confounding.

Although data for the study came from FY 2007, because the relationship was observed for all types of diagnosis-related visits, it suggests that the relationship between the quality measure and mortality is unlikely to substantially change with a different type of visit and therefore similar relationships with mortality should be observed today, even if the specific treatment processes have changed.

5. Conclusions

This is the first study to show an association between process–based quality measures and mortality for patients with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders and provides initial support for the predictive validity of the measures. Improving any of these process measures should be associated with lower mortality and increasing the number of diagnosis-related visits of any modality may be associated with decreased mortality risk in this population.

Highlights.

First study to validate quality measures for co-occurring disorders

4 out of 5 quality measures are associated with decreased mortality

Findings are unlikely to be the result of unmeasured confounders

Increasing the number of visits of any modality is likely to decrease mortality

Acknowledgments

Funding support: This work was supported by NIDA R01DA033953

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Central Arkansas Veteran Healthcare Center, Little Rock, AR. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01DA033953. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Dr. Watkins had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The authors acknowledge the editorial assistance of Tiffany Hruby, RAND Corporation and Carrie Edlund, MS, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. No additional compensation was received for their services.

Footnotes

For non-dichotomous predictors age and Charlson index, the odds ratios reflect the effect of age/10 and a change of 0.1 points in the Charlson comorbidity index, respectively.

Conflicts of interest: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Katherine E. Watkins, Email: kwatkins@rand.org.

Susan M. Paddock, Email: Paddock@rand.org.

Teresa J. Hudson, Email: Teresa.Hudson@va.gov.

Songthip Ounpraseuth, Email: stounpraseuth@uams.edu.

Amy M. Schrader, Email: amschrader@uams.edu.

Kimberly A. Hepner, Email: hepner@rand.org.

Greer Sullivan, Email: greer.sullivan@ucr.edu.

References

- Batki SL, Meszaros ZS, Strutynski K, Dimmock JA, Leontieva L, Ploutz-Snyder R, … Drayer RA. Medical comorbidity in patients with schizophrenia and alcohol dependence. Schizophrenia Research. 2009;107(2–3):139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilimoria KY. Facilitating quality improvement: Pushing the pendulum back toward process measures. JAMA. 2015;314(13):1333–1334. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowersox NW, Kilbourne AM, Abraham KM, Reck BH, Lai Z, Bohnert AS, … Davis CL. Cause-specific mortality among Veterans with serious mental illness lost to follow-up. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2012;34(6):651–653. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol deaths. 2014 Retrieved February 12, 2016, from http://www.cdc.gov/features/alcohol-deaths/

- Charbonneau A, Rosen AK, Ash AS, Owen RR, Kader B, Spiro A, III, … Kazis L. Measuring the quality of depression care in a large integrated health system. Medical Care. 2003;41(5):669–680. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000062920.51692.B4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2006;3(2):A42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland LA, Zeber JE, Wang CP, Parchman ML, Lawrence VA, Valenstein M, Miller AL. Patterns of primary care and mortality among patients with schizophrenia or diabetes: A cluster analysis approach to the retrospective study of healthcare utilization. BMC Health Services Research. 2009;9:127. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dafni U. Landmark analysis at the 25-year landmark point. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2011;4(3):363–371. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.957951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dausey DJ, Pincus HA, Herrell JM. Performance measurement for co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders. Substance abuse treatment, prevention, and policy. 2009;4:18. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-4-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis CL, Kilbourne AM, Blow FC, Pierce JR, Winkel BM, Huycke E, … Visnic S. Reduced mortality among Department of Veterans Affairs patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder lost to follow-up and engaged in active outreach to return for care. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(Suppl 1):S74–79. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Bucello C, Mathers B, Briegleb C, Ali H, Hickman M, McLaren J. Mortality among regular or dependent users of heroin and other opioids: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Addiction. 2011;106(1):32–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Singleton J, Calabria B, McLaren J, Kerr T, Mehta S, … Hall W. Mortality among cocaine users: A systematic review of cohort studies. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;113(2):88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1992;45(6):613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickey B, Dembling B, Azeni H, Normand SL. Externally caused deaths for adults with substance use and mental disorders. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 2004;31(1):75–85. doi: 10.1007/BF02287340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickey B, Normand SL, Weiss RD, Drake RE, Azeni H. Medical morbidity, mental illness, and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53(7):861–867. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.7.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druss BG, Bradford WD, Rosenheck RA, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. Quality of medical care and excess mortality in older patients with mental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58(6):565–572. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druss BG, Zhao L, Von Esenwein S, Morrato EH, Marcus SC. Understanding excess mortality in persons with mental illness: 17-year follow up of a nationally representative US survey. Medical Care. 2011;49(6):599–604. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31820bf86e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunigan R, Acevedo A, Campbell K, Garnick DW, Horgan CM, Huber A, … Ritter GA. Engagement in outpatient substance abuse treatment and employment outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 2014;41(1):20–36. doi: 10.1007/s11414-013-9334-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney JW, Humphreys K, Kivlahan DR, Harris AH. Why health care process performance measures can have different relationships to outcomes for patients and hospitals: understanding the ecological fallacy. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(9):1635–1642. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnick DW, Horgan CM, Acevedo A, Lee MT, Panas L, Ritter GA, … Wright D. Criminal justice outcomes after engagement in outpatient substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2014;46(3):295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnick DW, Lee MT, Chalk M, Gastfriend D, Horgan CM, McCorry F, … Merrick EL. Establishing the feasibility of performance measures for alcohol and other drugs. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;23(4):375–385. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00303-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnick DW, Lee MT, O’Brien PL, Panas L, Ritter GA, Acevedo A, … Godley MD. The Washington circle engagement performance measures’ association with adolescent treatment outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;124(3):250–258. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graubard BI, Korn EL. Predictive margins with survey data. Biometrics. 1999;55(2):652–659. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin BA, McCaffrey D, Ramchand R, Hunter SB, Suttorp M. Assessing the sensitivity of treatment effect estimates to differential follow-up rates: Implications for translational research. Health Services and Outcomes Research Methodology. 2012;12(2–3):84–103. doi: 10.1007/s10742-012-0089-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AH, Bowe T, Finney JW, Humphreys K. HEDIS initiation and engagement quality measures of substance use disorder care: Impact of setting and health care specialty. Population Health Management. 2009;12(4):191–196. doi: 10.1089/pop.2008.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AH, Ellerbe L, Phelps TE, Finney JW, Bowe T, Gupta S, … Trafton J. Examining the specification validity of the HEDIS quality measures for substance use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2015;53:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AH, Gupta S, Bowe T, Ellerbe LS, Phelps TE, Rubinsky AD, … Trafton J. Predictive validity of two process-of-care quality measures for residential substance use disorder treatment. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 2015;10:22. doi: 10.1186/s13722-015-0042-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AH, Humphreys K, Bowe T, Tiet Q, Finney JW. Does meeting the HEDIS substance abuse treatment engagement criterion predict patient outcomes? Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 2010;37(1):25–39. doi: 10.1007/s11414-008-9142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AH, Reeder RN, Ellerbe LS, Bowe TR. Validation of the treatment identification strategy of the HEDIS addiction quality measures: Concordance with medical record review. BMC Health Services Research. 2011;11:73. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes RD, Downs J, Chang CK, Jackson RG, Shetty H, Broadbent M, … Stewart R. The effect of clozapine on premature mortality: An assessment of clinical monitoring and other potential confounders. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2015;41(3):644–655. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Stark ME, Paredes A, Huang D, Anglin MD, Rawson R. A 12-year follow-up of a treated cocaine-dependent sample. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;30(3):219–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne AM, Farmer Teh C, Welsh D, Pincus HA, Lasky E, Perron B, Bauer MS. Implementing composite quality metrics for bipolar disorder: Towards a more comprehensive approach to quality measurement. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2010;32(6):636–643. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, Warren JL. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2000;53(12):1258–1267. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langendam MW, van Brussel GH, Coutinho RA, van Ameijden EJ. The impact of harm-reduction-based methadone treatment on mortality among heroin users. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(5):774–780. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.5.774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laramee P, Leonard S, Buchanan-Hughes A, Warnakula S, Daeppen JB, Rehm J. Risk of all-cause mortality in alcohol-dependent individuals: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. EBioMedicine. 2015;2(10):1394–1404. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MT, Horgan CM, Garnick DW, Acevedo A, Panas L, Ritter GA, … Reynolds M. A performance measure for continuity of care after detoxification: Relationship with outcomes. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2014;47(2):130–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin DY, Psaty BM, Kronmal RA. Assessing the sensitivity of regression results to unmeasured confounders in observational studies. Biometrics. 1998;54(3):948–963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenauer PK, Stefan MS, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Rothberg MB, Hill NS. Outcomes associated with invasive and noninvasive ventilation among patients hospitalized with exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA internal medicine. 2014;174(12):1982–1993. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Bucello C, Lemon J, Wiessing L, Hickman M. Mortality among people who inject drugs: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2013;91(2):102–123. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.108282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard C, Cox GB, Hall J, Krupski A, Stark KD. Substance use and five-year survival in Washington State mental hospitals. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2004;31(4):339–345. doi: 10.1023/b:apih.0000028896.44429.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittman BS, Hilborne LH, Brook RH. Developing Quality and Utilization Review Criteria from Clinical Practice Guidelines: Overview of the RAND method (PM-264-AHCPR) Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Morrill R, Cromartie J, Hart LG. Metropolitan, urban, and rural communting areas: Toward a better depiction of the U.S. settlement system. Urban Geography. 1999;20(8):727–748. [Google Scholar]

- Muhuri PK, Gfroerer JC. Mortality associated with illegal drug use among adults in the United States. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2011;37(3):155–164. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.553977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Committee for Quality Assurance. HEDIS 2013, volume 2: Summary table of measures, product lines and changes. 2013 Retrieved February 12, 2016, from http://www.ncqa.org/Portals/0/HEDISQM/HEDIS2013/List_of_HEDIS_2013_Measures_7.2.12.pdf.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Medical consequences of drug abuse. 2012 Retrieved February 12, 2016, from http://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/medical-consequences-drug-abuse/mortality.

- Newcomer JW, Hennekens CH. Severe mental illness and risk of cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2007;298(15):1794–1796. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.15.1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parast L, Doyle B, Damberg CL, Shetty K, Ganz DA, Wenger NS, Shekelle PG. Challenges in assessing the process-outcome link in practice. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2015;30(3):359–364. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3150-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks J, Svendsen D, Singer P, Foti ME, editors. Morbidity and mortality in people with serious mental illness (technical report 13) Alexandria, VA: National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Roerecke M. Reduction of drinking in problem drinkers and all-cause mortality. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2013;48(4):509–513. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agt021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roerecke M, Gual A, Rehm J. Reduction of alcohol consumption and subsequent mortality in alcohol use disorders: Systematic review and meta-analyses. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2013;74(12):e1181–1189. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13r08379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roerecke M, Rehm J. Alcohol use disorders and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2013;108(9):1562–1578. doi: 10.1111/add.12231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen CS, Kuhn E, Greenbaum MA, Drescher KD. Substance abuse-related mortality among middle-aged male VA psychiatric patients. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59(3):290–296. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.3.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott A, Guo B. HEN synthesis report. Copenhagen: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; 2012. For which strategies of suicide prevention is there evidence of effectiveness. [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK, Dennis ML, Laudet A, Funk RR, Simeone RS. Surviving drug addiction: The effect of treatment and abstinence on mortality. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(4):737–744. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.197038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shield KD, Rehm J, Rehm MX, Gmel G, Drummond C. The potential impact of increased treatment rates for alcohol dependence in the United Kingdom in 2004. BMC Health Services Research. 2014;14:53. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton J, Degenhardt L, Hall W, Zabransky T. Mortality among amphetamine users: A systematic review of cohort studies. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;105(1–2):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tondo L, Albert MJ, Baldessarini RJ. Suicide rates in relation to health care access in the United States: An ecological study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;67(4):517–523. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VA Information Resource Center. Calculating a comorbidity index for risk adjustment using VA or Medicare data. Hines, IL: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development Service, VA Information Resource Center; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(4):334–341. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins KE, Horvitz-Lennon M, Caldarone LB, Shugarman LR, Smith B, Mannle TE, … Pincus HA. Developing medical record-based performance indicators to measure the quality of mental healthcare. Journal for Healthcare Quality. 2011;33(1):49–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2010.00128.x. quiz 66–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins KE, Pincus HA, Paddock S, Smith B, Woodroffe A, Farmer C, … Call C. Care for veterans with mental and substance use disorders: Good performance, but room to improve on many measures. Health Affairs. 2011;30(11):2194–2203. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins KE, Smith B, Akincigil A, Sorbero ME, Paddock S, Woodroffe A, … Pincus HA. The quality of medication treatment for mental disorders in the Department of Veterans Affairs and in private-sector plans. Psychiatric Services. 2015 doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400537. 0(0), appi.ps.201400537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins KE, Smith B, Paddock SM, Mannle TE, Woodroffe A, Solomon J, … Pincus HA. Program evaluation of VHA mental health services: Capstone report (Contract # GS 10 F-0261K) Alexandria, VA: Altarum Institute and RAND-University of Pittsburgh Health Institute, RAND Corporation, TR-956; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wierdsma A, Mulder C, de Vries S, Sytema S. Reconstructing continuity of care in mental health services: A multilevel conceptual framework. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. 2009;14(1):52–57. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2008.008039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon YH, Chen CM, Yi HY, Moss HB. Effect of comorbid alcohol and drug use disorders on premature death among unipolar and bipolar disorder decedents in the United States, 1999 to 2006. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2011;52(5):453–464. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]