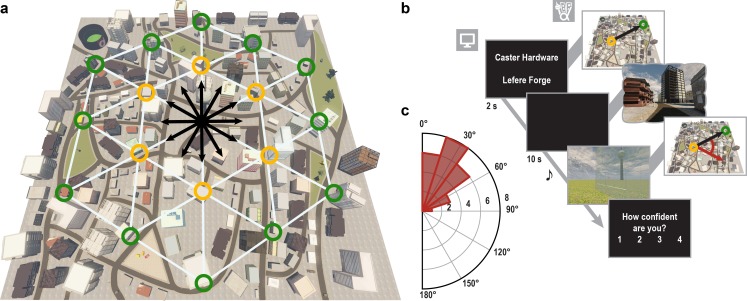

Figure 1. Direction-imagination task.

(a) Twelve evenly spaced directions were sampled using 18 buildings distributed regularly across Donderstown. We sampled each direction (indicated by black arrows) from different start locations (yellow circles), which dissociated the directions from visual features of imagined views (Figure 1—figure supplement 2), and employed a counterbalancing regime ensuring equal sampling of directions and start locations throughout the experiment (see Materials and methods). Buildings marked with a green circle served as target locations only. Importantly, the regular arrangement of building locations did not correspond to the street layout and was not revealed to participants, who experienced Donderstown only from a first-person perspective (see also Figure 1—figure supplement 1d). (b) Trials began with a cue indicating start (top building name) and target (bottom building name) location and thereby defining the relevant direction (black arrow). During an imagination period the screen was black and participants were instructed to imagine the view they would encounter when standing in front of the start building facing the direction of the target building. An auditory signal terminated the imagination period and participants indicated the imagined direction (red arrow) in a sparse VR environment, followed by a confidence judgment. Performance was measured as the absolute angular difference between the correct and the indicated direction (red arc). Note that only the bottom row of images was presented to participants, top row for illustration only. (c) Circular histogram of average absolute angular difference between correct and indicated directions across participants (mean error 33.68° ± 19.09° SD).

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.17089.003