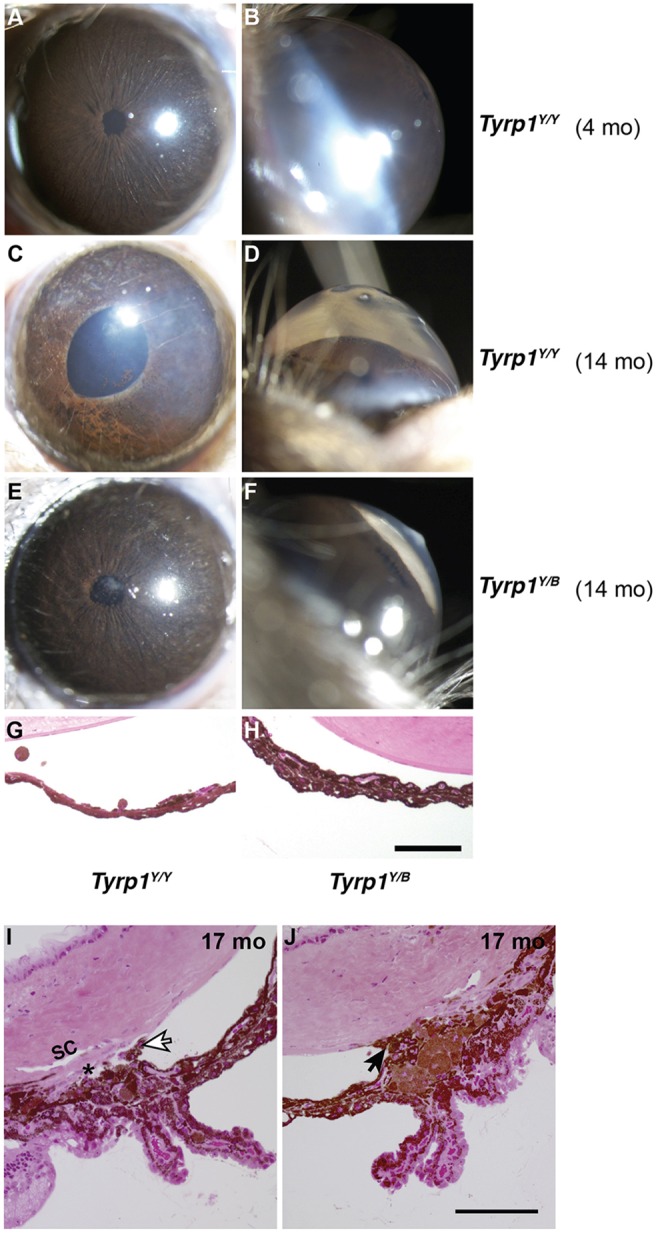

Fig. 4.

Iris disease and high IOP are genetically distinct. (A-F) Representative images (broad-beam illumination) of young control YBR mice (4 months) and old affected N2 mice (14 months) that are heterozygous or homozygous for the YBR-derived Tyrp1b allele. Y and B denote YBR and B6 alleles, respectively. (A-D) Mice that are homozygous for Tyrp1b (Tyrp1Y/Y) developed age-related iris stromal atrophy and their anterior chambers became deepened owing to high IOP. (E,F) Some heterozygous mice (Tyrp1Y/B), despite having an intact iris, developed high IOP (range 21.1-32.1 mmHg) and exhibited deep anterior chambers. This suggests that iris disease and high IOP are genetically separable. (G,H) Representative image of the iris from N2 mice (14 months) that are homozygous for the chromosome 17 (Y/Y) locus but are either homozygous (Tyrp1Y/Y) or heterozygous (Tyrp1Y/B) for Tyrp1. (I) Representative images from a histological evaluation of angles spanning much of the thickness of the eyes of Tyrp1Y/B mice (Materials and Methods). Despite high IOP, a normal iris and open angle was observed in most regions of this eye. White arrow indicates an iris process, a structure known to be in close proximity to the drainage tissue even in normal mouse eyes. Despite the sectioning-based distortion that displaced the iris processes towards the drainage structures, this section clearly shows a normal mouse open angle. (J) Although >60% of the extent of the angle was open in each of these eyes, there were local regions in which the angle was closed owing to anterior synechia (arrow). Local angle closure is common in non-glaucomatous mouse strains with normal IOP at this age, which is likely to be due to their naturally very narrow angles. Scale bars: 100 µm.