Abstract

The southern three-banded armadillo Tolypeutes matacus (Desmarest, 1804) is distributed from eastern Bolivia, south-west Brazil, the Gran Chaco of Paraguay and Argentina, and lives in areas with dry vegetation. This armadillo is one of the most frequently consumed species by people in this area. The objective of this work was test for zoonotic species among helminths in 12 intestinal tracts of T. matacus in a locality from the Argentinean Chaco (Chamical, La Rioja province). The parasites were studied with conventional parasite morphology and morphometrics, and prevalence, mean intensity and mean abundance were calculated for each species encountered. In the small intestine, seven species of nematodes and two species of cestodes were identified. In the large intestine, two species of nematodes were recorded. We did not find zoonotic species but have added new host records. This study in the Chaco region thus contributes to growing knowledge of the parasite fauna associated with armadillo species in this region.

Keywords: Argentinean Chaco, Zoonosis, Xenarthra, Helminths

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Tolypeutes matacus is one of the most consumed armadillo species by people.

-

•

Our objective was test for zoonotic species in intestinal tracts of T. matacus.

-

•

The parasites were studied by conventional morphometrics, location and descriptors.

-

•

Nine species of nematodes and two species of cestodes were identified.

-

•

We did not find zoonotic species but have added new host records.

1. Introduction

Some zoonotic infections cause disease in wildlife hosts, while many others exist “silently” in wildlife species as infections which are not apparent (Schwabe, 1969). This reflects a long evolutionary history of adaptation and the development of a balanced host-parasite relationship (Thompson, 2013). When such zoonoses infect humans it is usually as a consequence of human influence or activity (anthropogenic); this may be passive, as a result of poverty and other socioeconomic factors (e.g. Chagas disease), or may stem from activities such as recreational or subsistence hunting, which increase the risk of zoonotic transmission (Thompson, 2013).

The southern three banded armadillo Tolypeutes matacus (Desmarest, 1804) is distributed from Eastern Bolivia, south-western Brazil, south through the Gran Chaco of Paraguay, to central Argentina (Noss et al., 2014). In addition to its regional significance, this species is also of global interest because it is held in at least 113 zoos in Asia, Europe, North America and South America (International Species Information System, 2016). In contrast to other armadillos it does not have subterranean habits, using burrows abandoned by other species or hiding in dense vegetation (Redford and Eisenberg, 1992, Cuéllar, 2002, Noss, 2013). When individuals of this species are threatened, they can roll their body into a ball, an exclusive feature of the genus Tolypeutes (Meritt, 2008). Tolypeutes matacus is omnivorous, feeding mainly on invertebrates and to a lesser extent plant material, mainly fruits; the prevalence of each diet item is seasonal, so it is considered an insectivorous opportunist (Bolkovic et al., 1995, Cuéllar, 2008).

The IUCN lists T. matacus as Near Threatened because widespread habitat loss through much of its range and exploitation for food have caused significant decline (Noss et al., 2014). Furthermore, T. matacus has a slow reproduction rate; females give birth annually to a single young per litter (Noss et al., 2014).

The relationship between humans and xenarthrans dates back to ancient times, as indicated in early records of consumption and use by Native Americans and colonizers (Martinez and Gutierrez, 2004). Currently, T. matacus is consumed daily by people in all regions of South America (Cuéllar, 2000, Ojeda et al., 2002, Altrichter, 2006, Richard and Contreras Zapata, 2010). In the Argentinean Chaco, this armadillo is one of the most frequently consumed wild species (Altrichter, 2006). It is also used for other purposes, including as a pet, and its carapace, tail and skull are used as ornaments, knife handles, key chains, trophies (Altrichter, 2006, Richard and Contreras Zapata, 2010). In Bolivia it is the second-most hunted armadillo species by the Izoceño indigenous group (Cuéllar, 2000). Alves and Rosa (2007a) mention the use of the tail of Tolypeutes sp. to treat earache in the northeast Brazilian, and, according to street traders, the fat of the animal is consumed as a tea for diarrhea, headaches and asthma, or is rubbed onto inflamed areas as an ointment (Alves and Rosa, 2007b).

Studies in some localities from Paraguay, Bolivia and Argentina have reported the presence of several species of endoparasites in T. matacus, including nematodes, cestodes and acanthocephalans, some of them with known zoonotic importance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Previous records, descriptors and new records of parasites of Tolypeutes matacus from Chamical, La Rioja, Argentina.

| Helminth species |

P-MI – MA |

Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Nematoda | ||

| bAscarids | Deem et al., 2009 | |

| Aspidodera fasciata (Aspidoderidae) | 92%; 30(3–78); 27.5(0–78) | This study |

| Aspidodera scoleciformis (Aspidoderidae) | 92%; 136(20–441); 125(0–441) | Navone, 1990, Suare et al., 1997; Suare et al., 1998, Monferrán and Silverio Reyes, 2014; This study |

| Aspidodera sp. (Aspidoderidae) | Deem et al., 2009 | |

| aCyclobulura superinae (Subuluridae) | 8%; 1(1); 0.1(0–1) | This study |

| aDelicata ransomi (Molineidae) | 33%; 28(2–96); 9(0–96) | This study |

| Delicata sp. (Molineidae) | Suare et al., 1997 | |

| bDirofilaria immitis (Onchocercidae) | Deem et al., 2009 | |

| Heterakidae | Deem et al., 2009 | |

| Leipernema sp. (Strongyloididae) | Suare et al., 1997 | |

| Macielia elongata (Molineidae) | 8%; 16(16); 1(0–16) | Navone, 1990, Suare et al., 1997; Suare et al., 1998; Monferrán and Silverio Reyes, 2014; This study |

| Macielia sp. (Molineidae) | Suare et al., 1997 | |

| Mazzia bialata (Spirocercidae) | Navone, 1990 | |

| Moennigia virilis (Molineidae) | 100%; 388(1–3592); 388(1–3592) | Navone, 1990, Suare et al., 1997, Suare et al., 1998; This study |

| Orihelia anticlava (Onchocercidae) | Notarnicola and Navone, 2003 | |

| bOxyurids | Suare et al., 1998, Deem et al., 2009 | |

| Pterygodermatites chaetophracti (Rictulariidae) | 92%; 4.5(1–11); 4.2(0–11) | Navone, 1990, Suare et al., 1997, Suare et al., 1998; This study |

| Pterygodermatites sp. (Rictulariidae) | 75%; 5.2(1–15); 3.9(0–15) | Monferrán and Silverio Reyes, 2014; This study |

| Rhabditoidea | Suare et al., 1998 | |

| bStrongyloides sp. (Strongyloididae) | Deem et al., 2009 | |

| bStrongylus sp.(Strongylidae) | Deem et al., 2009 | |

| Trichohelix sp. (Molineidae) | Deem et al., 2009, Monferrán and Silverio Reyes, 2014 | |

| aTrichohelix tuberculata (Molineidae) | 17%; 9(1–17); 1.5(0–17) | This study |

| Trichostrongylidae | Deem et al., 2009 | |

| bTrichuris sp. (Trichuridae) | Deem et al., 2009 | |

| Cestoda | ||

| aMathevotaenia cf. argentinensis (Anoplocephalidae) | 25%; 11(1–32); 3(0–32) | This study |

| Mathevotaenia matacus (Anoplocephalidae) | Navone, 1990, Suare et al., 1997 | |

| Mathevotaenia sp. (Anoplocephalidae) | 25%; 2(1–4); 0.5(0–4) | Suare et al., 1998; This study |

| Acanthocephala | ||

| Oligacanthorhynchus carinii (Oligacanthorhynchidae) | Smales, 2007 | |

| Travassosia sp. (Oligacanthorhynchidae) | Navone, 1990, Suare et al., 1997 | |

P: Prevalence; MI: Mean Intensity (Range); MA: Mean Abundance (Range).

New host records.

Parasites with known zoonotic importance.

In view of the risks of parasites transmission associated with consumption and other uses of armadillos, the aim of this work was to test for zoonotic species by analyzing the composition and distribution of helminths in the intestinal tract of T. matacus in the department of Chamical, province of La Rioja, Argentina.

2. Materials and methods

This work was conducted in the department of Chamical, province of La Rioja, Argentina (30°21′ S, 66°18′ W). This area belongs to the Arid Chaco and it is characterized by an average temperature of 19.7 °C, total annual rainfall of 448.8 mm (Servicio Meteorológico Nacional, 2015), saline soils and forests of quebracho (Schinopsis sp.) and algarrobo (Prosopis sp.) (Morello et al., 2009).

The intestinal tracts of 12 individuals of T. matacus were examined. Five males, three females and four unsexed individuals were collected in 2006 and 2009 as part of a project of the Universidad Nacional de La Rioja (Sede Chamical) and donated to us by T. Rogel and A. Agüero (Transit guide No 000057–000058, 10 July 2009, see also Rogel et al., 2005). The intestines were fixed in a 10% formaldehyde solution and measured and dissected in the laboratory. Each was divided into two parts: the small intestine, which was further divided into ten segments of equal length, and the cecum and large intestine, which were examined in a single section. Intestinal contents were analyzed under stereoscopic binocular microscope (Olympus SZ61). Nematodes were preserved in 70% ethanol, cleared in lactophenol and mounted on a slide under a cover slip. Cestodes were stained with hydrochloric carmine, dehydrated in a series of ethanol solutions of increasing concentration, cleared with eugenol and mounted with Canada balsam on a slide under a cover slip. Both types of helminths were examined using an Olympus BX51 compound microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with camera lucida. CellSens v1.11 (Olympus) image analyzer software was used to take corresponding morphometric measurements for identification (X40-X600). Helminths were identified using the keys, descriptions and accounts of Navone and Lombardero, 1980, Navone, 1986, Navone, 1987, Navone, 1988, Anderson et al., 2009, Hoppe et al., 2009, Navone et al., 2010, and Ezquiaga and Navone (2013). Prevalence (P), mean intensity (MI) and mean abundance (MA) were calculated based on Bush et al. (1997).

3. Results

All individuals sampled were parasitized. Seven species of nematodes and two cestodes were identified in the small intestine; in the cecum and large intestine two species of nematodes were recorded (Table 1). None of the species observed had known zoonotic importance.

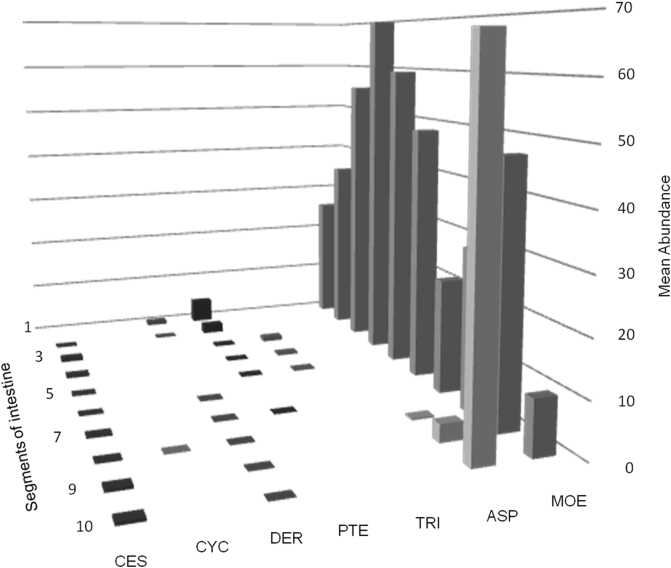

Helminths were found in all portions of the intestinal tract. (Fig. 1); Moennigia virilis was abundant throughout the small intestine. Two species of Aspidodera were recorded in the last two segments of the small intestine and in the cecum and large intestine. The remaining helminth species had lower abundance. Pterygodermatites spp. were located in the first five segments of the small intestine with higher abundance in the first and second segments.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of helminths in the small intestine of Tolypeutes matacus from Chamical, La Rioja, Argentina. MOE: Moennigia virilis, ASP: Aspidodera spp., TRI: Trichohelix tuberculata, PTE: Pterygodermatites spp., DER: Delicata ransomi, CYC: Cyclobulura superinae, CES: Cestoda.

Trichohelix tuberculata was located only in segments 3 to 5; Delicata ransomi was located in segments 1 and 2 and then from 6 to 10, being more abundant in the first segment; Cyclobulura superinae was found only in segment 8. Macielia elongata was observed but is not considered for this analysis because it inhabits the stomach; its presence in different locations of the intestine is attributed to post-mortem migration.

4. Discussion

The results obtained here provided new information on parasite-host associations, including the first records of C. superinae, T. tuberculata and D. ransomi in T. matacus. These parasite species had been reported in other armadillos in several regions of Argentina (Navone et al., 2010, Ezquiaga and Navone, 2013; Ezquiaga et al., 2015), which confirms their association with order Cingulata.

We studied several specimens of Pterygodermatites and observed that some individuals belonged to P. (P.) chaetophracti, and others to a yet undescribed species (Ezquiaga et al., unpublished results).

We distinguished two different cestode morphotypes, and identified two species belonging to the genus Mathevotaenia. One of the species, Mathevotaenia cf. argentinensis (Campbell et al., 2003), is a parasite of marsupials from the Chacoan region of Argentina (Campbell et al., 2003). The existence of parasites shared by xenarthrans and marsupials is plausible in light of their shared distribution and physiological and trophic similarities.

The omnivorous diet of T. matacus (Bolkovic et al., 1995) leads to an expectation of a parasite fauna with a variety of life cycles, and this was observed in our samples. For example, Macielia elongata, Aspidodera spp., Moennigia virilis, Trichohelix tuberculata and Delicata ransomi have direct life cycles and infect their host when it ingests the eggs on the ground (Navone, 1990). On the other hand, armadillos acquire Pterygodermatites spp., Cyclobulura superinae and Cestoda by ingesting infected arthropods like coleopterans and dermapterans (Navone, 1990, Navone et al., 2010). The parasite species richness found in this study (11 species) is greater than that recorded by Navone (1990) and Monferrán and Silverio Reyes (2014), and similar to that of Suare et al. (1997) and Deem et al. (2009).

The spatial distribution of parasites in the mammalian intestinal tract is poorly known (Durette-Desset et al., 1977) and our results should be considered preliminary. The patterns observed could be related to variation in the feeding guilds of parasites, their adaptations, and inter- and intra-specific competition.

Although zoonotic helminths were not observed, several have been recorded in T. matacus in North Chaco (Deem et al., 2009). It may be relevant that our work was conducted in the southern limit of the distribution T. matacus, and by necropsy.

Our work provided new parasite-host records, supporting the concept of hidden biodiversity (Luque, 2008). We also extended the geographic range of parasite species known in T. matacus and provide new data on their location in the intestinal tract. This report also has regional relevance, because T. matacus is the most frequently consumed armadillo in the entire Chaco (Argentina, Paraguay and Bolivia); it has global significance due to the large number of specimens living in zoos around the world.

To achieve complete knowledge of the parasitological fauna of T. matacus in the Argentinean Chaco, we propose that other organs (e.g., skeletal muscles, body cavity, blood samples) should be examined in animals collected in other parts of the region, and future studies should also employ coproparasitological analysis.

Conflicts of interest

This manuscript has not conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank Tania Rogel for providing the study material and Sean Locke for English review. This research was not supported by any specific funding agencies in public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Contributor Information

T.A. Ríos, Email: tatianaagustinarios@gmail.com.

M.C. Ezquiaga, Email: ceciliaezquiaga@yahoo.com.ar.

A.M. Abba, Email: abbaam@yahoo.com.ar.

G.T. Navone, Email: gnavone@cepave.edu.ar.

References

- Altrichter M. Wildlife in the life of local people of the semi-arid Argentine Chaco. Biodivers. Conserv. 2006;15:2719–2736. [Google Scholar]

- Alves R.R.N., Rosa I.L. Zootherapeutic practices among fishing communities in north and northeast Brazil: a comparison. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007;111:82–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves R.R.N., Rosa I.L. Zootherapy goes to town: the use of animal-based remedies in urban areas of NE and N Brazil. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007;113:541–555. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson R.C., Chabaud A.G., Willmott S. In: Keys to the Nematode Parasites of Vertebrates. Archival Volume. Anderson R.C., Chabaud A.G., Willmott S., editors. CABI Publishing; Nosworthy Way, Wallingford, Oxfordshire OX10 8DE, UK: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bolkovic M.L., Caziani S.M., Protomastro J.J. Food habits of the three-banded armadillo (Xenarthra: Dasypodidae) in the dry Chaco of Argentina. J. Mammal. 1995;76:1199–1204. [Google Scholar]

- Bush A.O., Lafferty K.D., Lotz J.M., Shostak A.W. Parasitology meets ecology on its own terms: Margolis et al. revisited. J. Parasitol. 1997;83:575–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M.L., Gardner S.L., Navone G.T. A new species of Mathevotaenia (Cestoda: Anoplocephalidae) and other tapeworms from marsupials in Argentina. J. Parasitol. 2003;89:1181–1185. doi: 10.1645/GE-1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuéllar E. Automonitoreo de la cacería de armadillos en el Izozog, Gran Chaco Boliviano. In: Cabrera E., Mercolli C., Resquin R., editors. Manejo de fauna silvestre en Amazonía y Latinoamérica. CITES Paraguay, Fundación Moises Bertoni, University of Florida; Asunción: 2000. pp. 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Cuéllar E. Census of the three-banded armadillo Tolypeutes matacus using dogs, southern Chaco, Bolivia. Mamm. 2002;66:448–451. [Google Scholar]

- Cuéllar E. Biology and ecology of armadillos in the Bolivian Chaco. In: Vizcaíno S.F., Loughry W.J., editors. The Biology of the Xenarthra. University of Florida Press; Gainesville: 2008. pp. 306–312. [Google Scholar]

- Deem S.L., Noss A.J., Fiorello C.V., Manharth A.L., Robbins R.G., Karesh W.B. Health assessment of free-ranging three-banded (Tolypeutes matacus) and nine-banded (Dasypus novemcinctus) armadillos in the gran Chaco, Bolivia. J. Zoo. Wildl. Med. 2009;40:245–256. doi: 10.1638/2007-0120.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durette-Desset M.C., Chabaud A.G., Cassone J. Neuf Nématodes Trichostrongyloïdes (don't sept nouveaux) coparasites d’un Fourmilier brésilien. Bull. Mus. Natn. Hist. Nat. 1977;298:133–158. Paris, 3° sér. n°428 Zoologie. [Google Scholar]

- Ezquiaga M.C., Rios T.A., Abba A.M., Navone G.T. A new rictularid (Nematoda: Spirurida) in xenarthrans from Argentina and new morphological data of Pterygodermatites (Paucipectines) chaetophracti. J. Parasitol., unpublished results. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ezquiaga M.C., Abba A.M., Navone G.T. Loss of taxonomic diversity of parasite species. The case of Chaetophractus villosus in Tierra del Fuego Island, Argentina. J. Helminthol. 2015;90:245–248. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X14000893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezquiaga M.C., Navone G.T. Trichostrongylina parasites of Dasypodidae (Xenarthra) from Argentina; a new species of Macielia (Molineidae: Anoplostrongylinae) in Chaetophractus vellerosus and redescription of Trichohelix tuberculata. J. Parasitol. 2013;99:821–826. doi: 10.1645/13-200.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe E.G.L., Araújo de Lima R.C., Tebaldi J.H., Athayde A.C.R., Nascimento A.A. Helminthological records of six-banded Armadillos Euphractus sexcinctus (Linnaeus, 1758) from the Brazilian semi-arid region, Patos county, Paraíba state, including new morphological data on Trichohelix tuberculata (Parona and Stossich, 1901) Ortlepp, 1922 and proposal of Hadrostrongylus ransomi nov. comb. Braz. J. Biol. 2009;69:423–428. doi: 10.1590/s1519-69842009000200027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Species Information System, 2016. http://www2.isis.org/AboutUs/Pages/Find-animals.aspx. Downloaded on 26 July 2016.

- Luque J.L. Parásitos: ¿Componentes ocultos de la Biodiversidad? Biol. (Lima) 2008;6:5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez G., Gutierrez M.A. Tendencias en la explotación humana de la fauna durante el Pleistoceno final y Holoceno en la Región Pampeana. In: Mengoni Goñalons G.L., editor. Zooarchaeology of South America. British Archaeological Reports; Argentina: 2004. pp. 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Meritt D. Xenarthrans of the Paraguayan Chaco. In: Vizcaino S.F., Loughry W.J., editors. The Biology of the Xenarthra. University Press of Florida; 2008. pp. 294–299. [Google Scholar]

- Monferrán M.C., Silverio Reyes M.J. Parásitos gastrointestinales de Tolypeutes matacus (Xenarthra; Dasypodidae), de Catamarca. Biol. Agron. 2014;4:87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Morello J.H., Rodríguez A.F., Silva M. Clasificación de ambientes en áreas protegidas de las ecorregiones del Chaco húmedo y Chaco seco. In: Morello J.H., Rodríguez A.F., editors. El Chaco Sin Bosques: la Pampa o el Desierto del Futuro. Orientación gráfica editora; Buenos Aires: 2009. pp. 53–89. [Google Scholar]

- Navone G.T. Estudios parasitológicos en edentados argentinos II.Nematodes parásitos de armadillos: Aspidodera fasciata (Schneider, 1866); A. scoleciformis (Diesing, 1851) y A. vazi Proenca, 1937 (Nematoda-Heterakoidea) Neotropica. 1986;32:71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Navone G.T. Estudios parasitológicos en edentados argentinos III. Nematodes trichostrongylidos Macielia elongata sp. nov.; Moennigia virilis sp. nov. y Trichohelix tuberculata (Parona y Stossich, 1901) Ortlepp, 1922 (Molineidae-Anoplostrongylinae) parásito de Chaetophractus villosus Desmarest y Tolypeutes matacus Desmarest (Xenarthra-Dasypodidae) Neotropica. 1987;33:105–117. [Google Scholar]

- Navone G.T. Estudios parasitológicos en edentados argentinos IV. Cestodes pertenecientes a la familia Anoplocephalidae Cholodkosky, 1902, parásitos de dasipódidos. Neotropica. 1988;34:51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Navone G.T. Estudio de la distribución, porcentaje y microecología de los parásitos de algunas especies de edentados argentinos. Stud. Neotrop. Fauna E. 1990;25:199–210. [Google Scholar]

- Navone G.T., Lombardero O. Estudios parasitológicos en edentados argentinos. I. Pterygodermatites (P) chaetophracti sp.nov. en Chaetophractus villosus y Dasypus hybridus (Nematoda-Spirurida) Neotropica. 1980;26:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Navone G.T., Ezquiaga M.C., Notarnicola J., Jimenez Ruiz A. A new species of Cyclobulura (Nematoda: Subuluridae) from Zaedyus pichiy and Chartophractus vellerosus (Xenarthra: Dasypodidae) in Argentina. J. Parasitol. 2010;96:1191–1196. doi: 10.1645/GE-2549.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noss A.J. Seguimiento del corechi (Tolypeutes matacus) por medio de carreteles de hilo en el Chaco boliviano. Edentata. 2013;14:15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Noss A.J., Superina M. and Abba A.M., Tolypeutes matacus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2014: e.T21974A47443233, Downloaded on 01 December 2015.

- Notarnicola J., Navone G.T. Systematic and distribution of Orihelia anticlava (Molin, 1858) (Nematoda: Onchocercidae) from dasypodids of South America. Acta Parasitol. 2003;48:103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda R.A., Borghi C.E., Roig V.G. Mamíferos de Argentina. In: Ceballos G., Simonetti J.A., editors. Diversidad y Conservación de los Mamíferos Neotropicales. CONABIO-UNAM; México, D. F.: 2002. pp. 23–63. [Google Scholar]

- Redford K.H., Eisenberg J.F. University of Chicago Press; Illinois, USA: 1992. Mammals of the Neotropics, The Southern Cone. Vol 2, Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay; p. 430. [Google Scholar]

- Richard E., Contreras Zapata D.I. Aportes al conocimiento de las estructuras de tráfico de fauna silvestre de Argentina. I. Relevamiento preliminar de la información y estructura interna del mercado. Rev. UNR Ambient. 2010;9:197–214. [Google Scholar]

- Rogel T.G., Pellegrini C.E., Agüero J.A., Bamba A.R., Paez P.C., Virlanga E.M. 2005. Caracterización de la dieta de dasipódidos del chaco arido riojano. Libro de resúmenes XX JAM; p. 128. [Google Scholar]

- Schwabe C.W. second ed. Williams and Wilkins; Baltimore: 1969. Veterinary Medicine and Human Health. [Google Scholar]

- Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. Valores medios de temperatura y precipitación- La Rioja- Chamical. http://www.smn.gov.ar/serviciosclimaticos/?mod=turismo&id=5&var=larioja. Downloaded on 30 March 2015.

- Smales L.R. Oligacanthorhynchidae (Acanthocephala) from mammals from Paraguay with the description of a new species of Neoncicola. Comp. Parasitol. 2007;74:237–243. [Google Scholar]

- Suare V., Bolkovic M.L., Navone G.T. 1997. Los parásitos del aparato digestivo de Tolypeutes matacus Desmarest (Edentata, Dasypodidae) aporte preliminar al conocimiento taxonómico y ecológico de la helmintofauna. Libro de resúmenes XII JAM; p. 120. [Google Scholar]

- Suare V., Bolkovic M.L., Navone G.T. 1998. Helmintos parásitos de dasipódidos del departamento de Copo, Provincia de Santiago del Estero, Argentina. Libro de resúmenes XIII JAM; p. 152. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R.C. Parasite zoonoses and wildlife: one health, spillover and human activity. Int. J. Parasitol. 2013;43:1079–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]