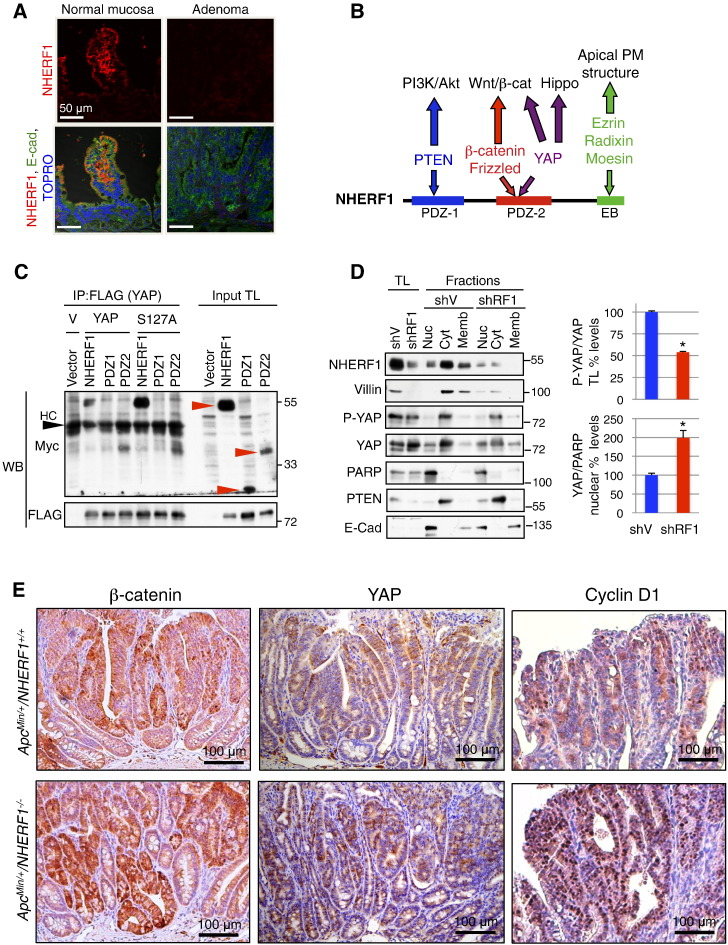

Figure 4.

NHERF1 deficiency promotes nuclear localization of β-catenin, YAP, and cyclin D1. (A) IF analysis of ApcMin/+NHERF1+/+ normal mucosa and adenomas with antibodies indicated on the left and TOPRO-3 highlighting nuclei shows strong NHERF1 expression at the apical PM of enterocytes from normal mucosa and loss of expression in adenoma. (B) Schematic domain structure of NHERF1 showing interactions with selected ligands involved in tumor growth and the pathways they control. EB, ERM-binding region. (C) Co-immunoprecipitation (IP) of proteins (400 μg) from total lysates (TL) of 293T cells coexpressing FLAG-tagged YAP wild type or YAP-S127A phosphorylation-deficient mutant and Myc-tagged NHERF1 full length and separate PDZ domains (red arrowheads). HC, heavy chain. V, YAP plasmid vector. Note interaction between NHERF1 full length or PDZ2 with either YAP wild type or S127A mutant. (D) Subcellular fractionation in nuclear (Nuc), cytoplasmic (Cyt), and membrane (Memb) fractions of Caco-2 CRC cells infected with either shRNA vector (shV) or shRNA-1 NHERF1 (shRF1). Proteins from total cell lysates (TL) and subcellular fractions were loaded at 20 μg per lane. PARP, PTEN, and E-cadherin were used as nuclear, cytoplasmic, and membrane fractionation markers, respectively. By using this procedure, it is known that cross contamination may occur between the nuclear fraction and membrane components, whereas the cytoplasmic fraction is pure. Normalized phosphorylated YAP (P-YAP) to YAP expression in total lysates and normalized nuclear YAP to PARP expression are represented as mean ± SD in control and NHERF1 knockdown Caco-2 cells. *P < .05. E. IHC with β-catenin, YAP, and cyclin D1 antibodies shows higher expression of these proteins in ApcMin/+NHERF1−/− tumors compared to control. Nuclear expression is elevated for β-catenin and YAP in ApcMin/+NHERF1−/− tumors, and very prominent for cyclin D1.