Abstract

This randomized controlled trial (RCT) evaluated the efficacy of the Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies curriculum (PATHS; Kusche & Greenberg, 1994) as a means to improve children's social–emotional competence (assessed via the Social Skills Improvement System (SSIS); Gresham & Elliot, 2008) and mental health outcomes (assessed via the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ); Goodman, 1997). Forty-five schools in Greater Manchester, England, were randomly assigned to treatment and control groups. Allocation was balanced by proportions of children eligible for free school meals and speaking English as an additional language via minimization. Children (N = 4516) aged 7–9 years at baseline in the participating schools were the target cohort. During the two-year trial period, teachers of this cohort in schools allocated to the intervention group delivered the PATHS curriculum, while their counterparts in the control group continued their usual provision. Teachers in PATHS schools received initial training and on-going support and assistance from trained coaches. Hierarchical linear modeling of outcome data was undertaken to identify both primary (e.g., for all children) and secondary (e.g., for children classified as “at-risk”) intervention effects. A primary effect of the PATHS curriculum was found, demonstrating increases in teacher ratings of changes in children's social–emotional competence. Additionally, secondary effects of PATHS were identified, showing reductions in teacher ratings of emotional symptoms and increases in pro-social behavior and child ratings of engagement among children identified as at-risk at baseline. However, our analyses also identified primary effects favoring the usual provision group, showing reductions in teacher ratings of peer problems and emotional symptoms, and secondary effects demonstrating reductions in teacher ratings of conduct problems and child ratings of co-operation among at-risk children. Effect sizes were small in all cases. These mixed findings suggest that social and emotional learning interventions such as PATHS may not be as efficacious when implemented outside their country of origin and evaluated in independent trials.

Keywords: Social and emotional learning, Mental health, Universal, Elementary school, Randomized trial

1. Introduction

The onset of mental health problems is characterized by changes in thought, mood and/or behavior that impair functioning (Murphey, Barry, & Vaughn, 2013). This includes emotional symptoms, conduct problems, inattention and hyperactivity, and peer problems (Goodman, 1997). By 2030, mental health difficulties will yield the most significant disease burden in high-income countries, accounting for up to 10% of disability-adjusted-life-years (Mathers & Loncar, 2006). Global epidemiological data suggests up to 20% of children and adolescents experience chronic, clinically significant mental health difficulties and half of adult mental health problems originate during the school years (Belfer, 2008). The individual and societal impacts throughout the life course are huge, and include reduced quality of life, lost economic productivity, destabilization of communities, and higher rates of health, special education and social care service utilization (Belfer, 2008). In England, the annual financial cost of mental health problems is estimated to be £105 billion (Center for Mental Health, 2010).

Early intervention and prevention of mental health problems have therefore become a policy priority (Allen, 2011, Davies, 2012, Department for Education, 2014a). Schools can and should be a principal vehicle for this. Universal interventions, in which services are delivered to all children, irrespective of risk status, have grown significantly in popularity in recent years (Humphrey, 2013). Their theorized outcomes can be dichotomized into primary (e.g., preventing the onset of symptoms across the general population of students) and secondary (e.g., preventing the maintenance or progression of symptoms among those classified as “at-risk”) effects (O'Connell, Boat, & Warner, 2009).

Evidence-informed universal interventions delivered in schools hold particular promise for a number of reasons. First, developmental theory and research suggest that what happens early in life influences health and wellbeing later in life. Hence, “prevention pays” (Davies, 2012), both in economic and quality of life terms. Second, schools play a central role in the lives of children and their families, and their reach is unparalleled (Greenberg, 2010). As a consequence, classroom-based interventions can influence outcomes for children who would not otherwise access the support they need through usual care pathways (e.g., it is estimated that 75% of children with significant mental health difficulties do not access appropriate specialist services; Dvorsky et al., 2014, Kelvin, 2014). Third, universal school-based preventive interventions are by definition more inclusive and less stigmatizing (Humphrey, 2013, Stallard et al., 2012), and can circumvent some of the unintended consequences of targeted/indicated approaches (e.g., “deviancy training”; Evans, Scourfield, & Murphy, 2014). Fourth, health economic analyses of the effects of early onset mental health problems on adult labor market outcomes suggest large indirect effects operating through education (Johar & Truong, 2014).

Social and emotional learning (SEL) is one approach to universal school-based prevention of mental health problems. SEL interventions seek to develop children's social–emotional competencies (e.g., self-control, empathy; Gresham & Elliot, 2008), typically through the implementation of a taught curriculum, modifications to school ethos/climate, and/or work with families and communities (Humphrey, 2013). SEL theory frames these competencies as key protective factors that can enhance resilience to the onset, maintenance, or progression of mental health difficulties. Longitudinal evidence from cohort studies supports this assertion (e.g., Goodman, Joshi, Nasim, & Tyler, 2015).

The empirical basis supporting the use of SEL interventions is growing. Three recent meta-analyses have provided robust evidence demonstrating their efficacy in improving children's social–emotional competencies and reducing mental health problems, in addition to a range of other salient outcomes (Durlak et al., 2011, Sklad et al., 2012, Wigelsworth et al., 2016). However, most trials (87%) have been conducted in the United States (US) to date (Durlak et al., 2011), and transferability cannot be assumed (Weare & Nind, 2011). This is particularly true in cases where evidence-based interventions are ‘exported’ to other countries and cultures, as the evidence suggests that their effects on certain key outcomes (including social–emotional competence, pro-social behavior and emotional symptoms) can become diluted (Wigelsworth et al., 2016). Perceived lack of fit of between a given program and the needs, values, and expectations of adopters may act as a significant barrier to implementation, and as such a major factor in the successful transportability of interventions is their adaptability (Castro, Barrera, & Martinez, 2004). In the case of the PATHS curriculum that is the focus of this paper, a process of cultural adaptation was undertaken by staff at Barnardo's (the children's charity who own the UK license to distribute PATHS) in order to “Anglicize” the materials. These were primarily surface level changes (e.g., modified vocabulary, photographs and names, changes to cultural references).

An additional issue is that a significant proportion (66%) of studies to date have been led by (or involved) intervention developers (Wigelsworth et al., 2016). In other disciplines there is evidence that developer involvement can lead to significantly inflated treatment effects, either through bias, higher quality implementation, or a combination of these two factors (Eisner, 2009). Independent replication in SEL is therefore absolutely essential (Lendrum & Wigelsworth, 2013). Finally, a need for subgroup analyses has been identified, in order to determine if participant characteristics are related to differential program effects (e.g., do children with certain characteristics benefit more than others from SEL interventions; Durlak et al., 2011). This is particularly true of children considered to be at-risk in view of their nascent mental health difficulties, for whom SEL programs are theorized to prevent the progression of symptoms by imparting skills that promote resilience (Humphrey, 2013).

1.1. The Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies (paths) curriculum

PATHS is a universal SEL intervention that aims to help all children (aged 4–11) manage their behavior, understand their emotions, and work well with others. It is designed to be delivered by classroom teachers and includes a series of lessons on topics such as identifying and labeling feelings; generalization activities and techniques that support the application of new skills during the school day; and parent materials that aim to extend learning to the home environment (see Intervention in Method section for a detailed description). It is one of only 14 interventions (in a review of over 1300) to be designated as a “model program” by the Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence (2016).

Multiple randomized trials have demonstrated meaningful effects of PATHS on a range of outcomes, including social–emotional competence (Domitrovich et al., 2007, Greenberg et al., 1995), mental health (Crean & Johnson, 2013), and academic attainment (Schonfeld et al., 2014). These trials have also indicated that such effects can be replicated in special education populations (Greenberg & Kusche, 1998) and are sustained over time (Kam, Greenberg, & Kusche, 2004). Finally, there is also sound evidence that PATHS delivered in combination with targeted interventions leads to improvements in social–emotional and mental health outcomes for children classified as at-risk (e.g., with elevated levels of aggression at baseline; Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2010).

On the basis of the above evidence, PATHS has become one of the most widely disseminated SEL interventions. It is somewhat unique in having been subjected to independent evaluations within and beyond its country of origin (Wigelsworth et al., 2016). However, these independent trials have produced mixed findings. For example, a small-scale independent quasi-experimental study conducted in the United States (US) found a modest treatment effect for social–emotional competence (Seifer, Gouley, Miller, & Zakriski, 2004). However, a large independent randomized trial in the same country (Social and Character Development Research Consortium, 2010) found no significant impact of PATHS on children's social–emotional competence, behavior, or academic outcomes (although a subsequent paper published from this trial reported significant impacts on conduct problems and aggression; Crean & Johnson, 2013). Finally, the recent independent Head Start CARES (Classroom-based Approaches and Resources for Emotion and Social skill promotion) trial, also based in the US, produced inconsistent results. Thus, while small-to-moderate intervention effects of the Preschool PATHS curriculum were found in relation to the emotion knowledge, social problem solving skills, learning and social behaviors of 4-year old children in the trial (Morris et al., 2014), no such effects were found for 3-year olds (Hsueh, Lowenstein, Morris, Mattera, & Bangser, 2014).

Outside of the US, an independent randomized trial conducted in Switzerland reported significant effects of PATHS on aggressive and inattentive/hyperactive behavior that were sustained over time, but no effect on social–emotional competence (Malti et al., 2011, Malti et al., 2012). In Turkey, a small-scale, independent quasi-experimental study of the Preschool PATHS curriculum found intervention effects in relation to children's aggressive and disruptive behavior, concentration and attention, and social–emotional competence (Arda & Ocak, 2012). However, an independent quasi-experimental trial in the Netherlands failed to find any impact on social–emotional competence or mental health outcomes (Goossens et al., 2012). These variable findings may be attributable to developer influence in non-independent trials (e.g., bias or higher quality implementation; Eisner, 2009) and/or problems associated with cultural transferability (Wigelsworth et al., 2016).

1.2. The current study

The trial reported herein was conducted in the United Kingdom (UK), where PATHS was recommended for widespread adoption in an influential report to the government on early intervention (Allen, 2011). The UK evidence base for PATHS is equivocal. Two small scale quasi-experimental studies have produced promising evidence of effects on both social–emotional competence and mental health (Curtis and Norgate, 2007, Hughes and Cline, 2014). However, a recent randomized trial conducted in Birmingham, England, yielded completely null results in terms of primary effects, although subgroup analyses did identify a secondary intervention effect for children with elevated levels of emotional symptoms at baseline (Berry et al., 2015, Little et al., 2012). Finally, a trial in Belfast, Northern Ireland, showed effects on social–emotional competence that were, “weak and inconsistent, but generally in a positive direction” (Ross, Sheard, Cheung, Elliott, & Slavin, 2011, p.61).

The current study was commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (grant reference: 10/3006/01). In light of the above research, our aim was to contribute to knowledge regarding the effects of PATHS (and by extension, universal SEL interventions more generally) when evaluated independently outside its country of origin (Wigelsworth et al., 2016). We also sought to further an understanding of differential program benefits for at-risk children (Durlak et al., 2011). Finally, we intended to address a critical gap in the evidence base for PATHS by examining its effects on older children. The early intervention emphasis in the program has meant that the overwhelming majority of the studies outlined above focused on children in pre-school or early elementary school settings. Few PATHS trials have focused on children older than seven to date (e.g., Schonfeld et al., 2014, Social and Character Development Research Consortium, 2010).

Three hypotheses are tested. First, we predicted that children in primary schools implementing PATHS over a two-year period would demonstrate significant improvements in social–emotional competence when compared to those children attending control schools (H1 — primary effect, social–emotional competence). Second, we hypothesized that children in PATHS schools would demonstrate significant reductions in mental health difficulties compared to those in control schools (H2 — primary effect, mental health). Third, we expected differential intervention effects among children classified as at-risk at baseline on the various outcomes measures used (e.g., children with elevated levels of emotional symptoms in the intervention group would demonstrate greater symptom reduction than their counterparts in the control group and those without elevated symptoms in either group; H3 — secondary effects, social–emotional competence, H3a, and mental health, H3b).

2. Method

2.1. Design

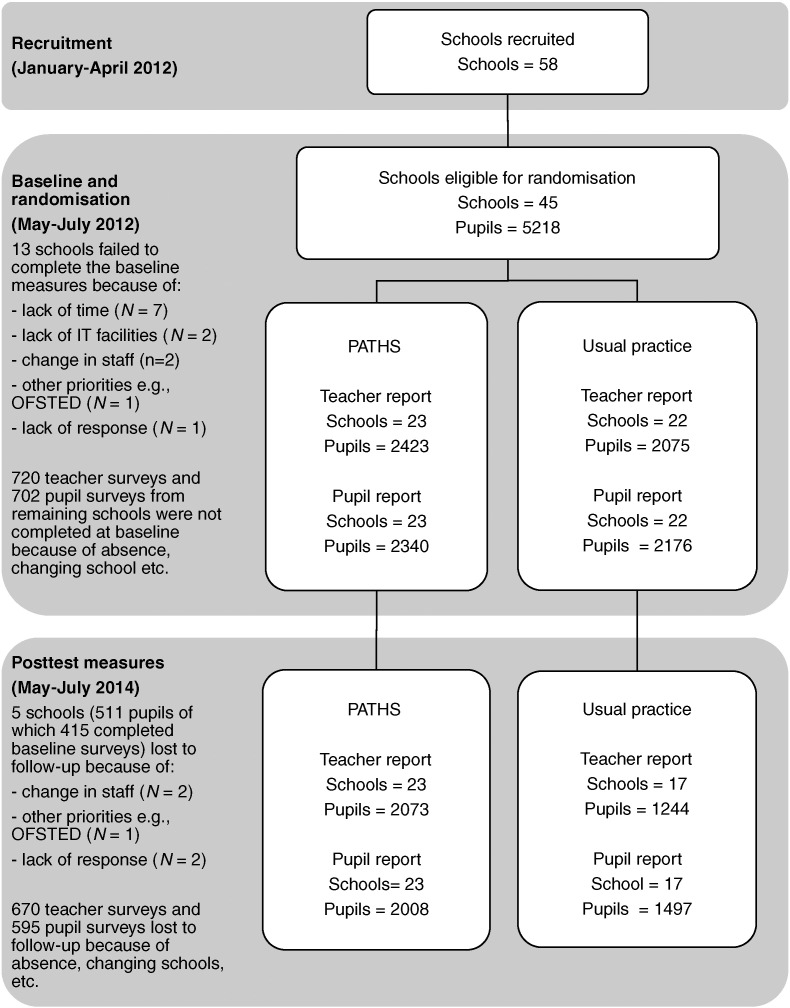

A two group parallel cluster RCT (Puffer, Torgerson, & Watson, 2005) was undertaken, with schools as the unit of randomization (see Fig. 1 for flow of clusters and individual participants through the study). Random allocation of schools was conducted independently of the research team by the Clinical Trials Unit at the Manchester Academic Health Science Center, and was balanced by proportions of children eligible for free school meals (FSM) and speaking English as an additional language (EAL) via minimization. Minimization is considered to be the “platinum standard” for trials, conferring the benefits of randomization in terms of rigor and causal inference, while also guaranteeing similarity of groups (Treasure & MacRae, 1998, p.362).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT diagram depicting flow of schools and children through the PATHS trial.

Eligible schools were mainstream, state-maintained institutions, providing education for children from the ages of 4–11 years in the 10 Local Authorities that form the Greater Manchester region. Children attending the participating schools who were aged 7–9 years (e.g., Years Groups 3–5) at baseline were the target population. Participation required consent from the schools' Head Teachers. Child assent and parental opt-out consent were also sought. The study received ethical approval from the University of Manchester Research Ethics Committee (Ref: 11,470). In total 140 parents (2.6%) exercised their right to opt their children out of the trial, and no children declined assent or exercised their right to withdraw from the study.

2.2. Participants

Sample characteristics at baseline by trial group are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics at baseline by trial arm (values are numbers (percentages) unless otherwise stated).

| PATHS (N = 2340) | Usual school provision (N = 2176) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 1161 (49.6) | 1152 (52.9) |

| Female | 1179 (50.4) | 1024 (47.1) | |

| Year group | Year 3 | 760 (32.5) | 686 (31.5) |

| Year 4 | 796 (34.0) | 782 (35.9) | |

| Year 5 | 784 (33.5) | 708 (32.5) | |

| FSM eligibility | Yes | 720 (31.7) | 621 (29.6) |

| No | 1550 (68.3) | 1478 (79.6) | |

| Ethnicity | White | 1632 (72.8) | 1419 (68.5) |

| Black | 22 (9.9) | 114 (5.5) | |

| Asian | 196 (8.7) | 317(15.3) | |

| Chinese | 13 (0.6) | 13 (0.6) | |

| Mixed | 107 (4.8) | 152 (7.3) | |

| Other | 61 (2.7) | 51 (2.5) | |

| Unclassified | 10 (0.4) | 7 (0.3) | |

| First language | English | 1783 (78.5) | 1590 (78.5) |

| Other | 482 (21.2) | 509 (24.2) | |

| SEND provision | None | 1850 (81.5) | 1665 (79.3) |

| School action | 291 (12.8) | 274 (13.1) | |

| School action Plus | 116 (5.1) | 139 (6.6) | |

| Statement | 13 (0.6) | 21 (1.0) | |

| Mean (SD) | N(%) at risk | Mean (SD) | N(%) at risk | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher-rated SDQ | Emotional symptoms | 1.59 (2.15) | 272 (11.2) | 1.62 (2.08) | 231 (11.1) |

| Conduct problems | 1.08 (1.81) | 404 (16.7) | 1.05 (1.80) | 339 (16.3) | |

| Hyperactivity | 3.07 (3.07) | 511 (21.1) | 3.17 (3.02) | 438 (21.1) | |

| Peer problems | 1.18 (1.71) | 259 (10.7) | 1.31 (1.69) | 231 (11.1) | |

| Pro-social | 7.72 (2.46) | 501 (20.7) | 7.43 (2.42) | 520 (25.1) | |

| Total difficulties | 6.92 (6.32) | 495 (20.4) | 7.15 (6.19) | 460 (22.2) | |

| Child-rated SSIS | Total | 103.16 (19.9) | N/A | 103.75 (20.40) | N/A |

| Communication | 15.02 (3.64) | 162 (7.0) | 14.65 (3.18) | 183 (7.2) | |

| Cooperation | 17.22 (3.64) | 249 (10.7) | 16.92 (3.75) | 268 (12.4) | |

| Assertion | 14.86 (3.90) | 281 (12.1) | 14.18 (4.03) | 296 (13.7) | |

| Responsibility | 16.33 (3.55) | 172 (7.4) | 16.02 (3.66) | 202 (9.3) | |

| Empathy | 14.63 (3.14) | 172 (7.4) | 14.25 (3.27) | 202 (9.3) | |

| Engagement | 15.98 (3.68) | 239 (10.3) | 15.49 (3.84) | 290 (13.5) | |

| Self-control | 12.02 (4.22) | 298 (12.8) | 11.77 (4.12) | 285 (13.2) |

Note. SEND = Special education needs and disability, SDQ = Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, SSIS = Social Skills Improvement System.

2.2.1. Schools

Fifty-eight schools were recruited, of whom 45 met the eligibility criteria for randomization, which included completion of baseline measures and signing a memorandum of agreement to adhere to the trial protocol. Excluded schools were those who failed to complete baseline measures, most frequently citing a lack of time to do so (see Fig. 1). Participating schools were representative of norms in England in terms of size, attendance, attainment and the proportion of children identified as having special educational needs, but had higher proportions of children eligible for FSM and speaking EAL than national averages (Department for Education, 2010, Department for Education, 2012, Department for Education, 2013, Department for Education, 2014b).

2.2.2. Pupils

Baseline data was available for 4516 children in Years Groups 3–5 (aged 7–9 years) in participating schools. Their characteristics mirrored those of primary schools in England closely, albeit with a similar pattern of deviation in terms of FSM and EAL to that noted above (Department for Education, 2010, Department for Education, 2012, Department for Education, 2013, Department for Education, 2014b). The proportion of children classified as at-risk on the various outcome measures was consistent with norms published by the instruments' respective developers (Goodman, 1997, Gresham and Elliot, 2008).

2.3. Intervention

PATHS is based on the Affective-Behavioral-Cognitive-Developmental model of development, which emphasizes the developmental integration of affect, emotion language, behavior and cognitive understanding to promote social–emotional competence (Greenberg & Kusche, 1993). Core program components are a taught curriculum, generalization activities and techniques, and parent materials, to which all children in a given class are exposed. Curriculum packs are provided for each class containing lessons and send-home activities that cover topics such as identifying and labeling feelings, controlling impulses, reducing stress and understanding other people's perspectives, in addition to associated physical resources and artifacts (e.g., posters, feelings dictionaries). In the current study, class teachers were also given an implementation guidance manual developed by the research team that emphasized the PATHS program theory and the importance of effective implementation (available on request from the research team).

PATHS lessons follow a common format that includes an introduction from the teacher (in which the lesson topic and objectives are introduced), a main activity (often built around a group activity or story), and a brief plenary/closure (in which learning is reviewed). Frequent prompts to elicit pupil responses and clarify learning are included throughout. The program utilizes a “spiral” curriculum model, whereby (i) topics and concepts are revisited; (ii) units and lessons are developmentally sequenced; (iii) new learning is linked to previous learning; and (iv) the competence of learners increases with each successive visit to a topic or concept.

PATHS is designed to be delivered by class teachers in general education classrooms. In the current trial, the curriculum was implemented by classroom teachers in Years Groups 3, 4, and 5 (Years Groups 4, 5, and 6 in the second year of the trial). All were qualified teachers and had an average of eight years teaching experience, and 81% were female. Delivery of teacher-led PATHS lessons to all children was undertaken as part of the normal class timetable. Generalization activities and strategies were implemented routinely throughout the school day. PATHS lessons last approximately 30–40 mins and are designed to be delivered twice-weekly throughout the school year. Curriculum packs contain an average of 40 lessons.

Teachers in PATHS schools received one full day of initial training with a half-day follow-up four months later. Training was led by certified trainers from Pennsylvania State University (PSU) and included a range of activities designed to familiarize teachers with PATHS theory, concepts and materials. For example, one activity required teachers to work in groups to explore a PATHS lesson and discuss key questions relating to how they would implement it. In a survey administered by the research team, 84% of teachers agreed or strongly agreed that the training they had received was sufficient to enable them to deliver PATHS effectively. In addition to this training, teachers in PATHS schools received on-going technical support and assistance (e.g., lesson modeling, observation and feedback) from three members of the research team (Joyce, Pert, Stephens), who were themselves trained by PSU staff and received on-going supervision throughout the trial, and 82% of teachers agreed or strongly agreed that this coaching helped them to deliver PATHS more effectively.

2.4. Implementation

Implementation fidelity, dosage, quality, reach and responsiveness were assessed via structured observations conducted by three research assistants. The observation schedule was developed by the research team, drawing upon existing rubrics and schedules utilized in previous studies of the implementation of PATHS (e.g., Faria et al., 2013, Kam et al., 2003), advice from the program developer and colleagues at the Prevention Research Center at PSU, and the extant literature on the assessment of implementation (e.g., O'Donnell, 2008). For fidelity, quality, and responsiveness, observers were required to rate the PATHS lesson from 0 to 10 according to a number of indicators. For example, quality was assessed via ratings of the teacher's preparedness, interest and enthusiasm, clarity of expression, and responsiveness to students. Reach was assessed via determination of the proportion of the class that was present while the PATHS lesson was being delivered. Finally, dosage was assessed by computing the differential between actual and expected lesson delivery at the time of observation, with the lesson delivery schedule in PATHS implementation manual used as a guide for the latter.

The schedule and accompanying rubric were piloted and refined using video footage of PATHS implementation in English schools recorded in a previous trial (Little et al., 2012). Following this, additional footage was used in order to generate inter-rater reliability data. Given the number of raters (more than two) and the response format of the coding schedule (ordinal), the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) was used. ICC values can range between − 1 and 1, with higher scores being indicative of limited variation between raters. The overall ICC was determined to be 0.91. As this level of agreement is considered to be “excellent” (Hallgren, 2012, p.9), adequate consistency among raters was deemed to have been achieved. However, during the live trial observations, a senior member of the research team responsible for assessment of implementation sat in on a randomly selected 10% of the live observations in order to moderate ratings and guard against “drift” over time.

Mean scores for fidelity (8.20), quality (8.48), participant responsiveness (7.34), and reach (91%) were all high. However, mean dosage scores indicated that classes were on course to deliver only 20 of the approximately 401 PATHS lessons in a given year. Thus, PATHS lessons were generally implemented very well, but not at the frequency recommended by the intervention developers (PATHS to Success Research Team, 2015). However, less than optimal dosage is not at all unusual in studies of PATHS. Although infrequently reported, those that provide dosage data typically report average lesson completion rates of around 50% (e.g., Berry et al., 2015, Faria et al., 2013). Furthermore, a dose–response relationship has yet to be established consistently for PATHS (see for example, Goossens et al., 2012), and there is certainly no evidence of a clear threshold for “minimum effective dose” (Liu, 2010, p.799). Finally, the median number of sessions delivered in SEL interventions reported in Durlak et al.’s (2011) meta-analysis of universal SEL interventions was 24; this figure is in line with the dosage rate reported here.

2.5. Other SEL practice

Existing practice in SEL at both universal and targeted levels was assessed via school-level surveys completed by the member of staff with lead responsibility for personal, social and health education. The research team generated an exhaustive list of proprietary SEL and SEL-related interventions that were known to be available in the UK at the time of the trial: 10 universal interventions (e.g., the primary social and emotional aspects of learning program, whole school element) and nine targeted interventions (e.g., nurture groups). As a mechanism to determine response validity, an additional intervention name created by the research team (“Friends Forever”) was also included in the survey. For each intervention, respondents were required to endorse the level of implementation in their school on a scale from 0 to 3 (not implementing/just getting started/well underway/fully embedded). No respondents endorsed the intervention created by the research team. A composite score was created for both universal (possible range 0–30) and targeted SEL provision (0–27) for use in analysis.

Schools in both groups reported moderate levels of SEL-related activity at baseline. Those in the control group reported significant increases in the use of both universal and targeted SEL initiatives through the course of the trial, F(1, 34) = 5.85, p = .02 (see Table 2). This may be attributable to a so-called “John Henry effect” (also known as compensatory rivalry) or a response to increased awareness of mental health difficulties brought about through involvement in the baseline outcome assessments, for which there is a parallel empirical precedent in the healthcare literature (Steventon et al., 2012). In light of this, we incorporated the changes in other SEL practice at universal and targeted levels reported by schools as explanatory variables at the school level in our analyses (see Table 3, Table 4, Table 5). This enabled us to examine the impact of PATHS while controlling for changes in other SEL practice in both groups of the trial, thereby allowing us to rule out “compensatory rivalry” as an explanation for our findings.

Table 2.

Mean (SD) scores for other SEL practice (universal and targeted), teacher (SECCI) and child (SSIS) ratings of social–emotional competence, and teacher ratings of mental health (SDQ).

| PATHS |

UP |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Final | Baseline | Final | ||

| School | Other SEL practice | ||||

| Universal | 9.24 (4.54) | 9.32 (4.93) | 7.90 (2.57) | 9.76 (5.93) | |

| Targeted | 4.48 (3.68) | 4.27 (3.49) | 4.00 (3.45) | 5.76 (5.20) | |

| Pupil | SECCI | – | 0.69 (0.67) | – | 0.46 (0.64) |

| SDQ | |||||

| Emotional symptoms | 1.59 (2.15) | 1.40 (1.93) | 1.62 (2.08) | 1.33 (2.02) | |

| Conduct problems | 1.08 (1.81) | 0.90 (1.56) | 1.05 (1.80) | 0.83 (1.51) | |

| Hyperactivity | 3.07 (3.07) | 2.54 (2.71) | 3.17 (3.02) | 2.55 (2.67) | |

| Peer problems | 1.18 (1.71) | 1.12 (1.67) | 1.31 (1.69) | 1.05 (1.61) | |

| Pro-social | 7.72 (2.46) | 7.86 (2.30) | 7.15 (6.19) | 7.63 (2.37) | |

| Total difficulties | 6.92 (6.32) | 5.97 (5.74) | 7.15 (6.19) | 5.75 (5.60) | |

| SSIS | |||||

| Total | 103.16 (19.9) | 103.75 (19.39) | 103.47 (20.40) | 102.00 (20.03) | |

| Communication | 15.02 (3.64) | 14.94 (2.94) | 14.65 (3.18) | 14.65 (3.09) | |

| Cooperation | 17.22 (3.64) | 16.88 (3.63) | 16.92 (3.75) | 16.85 (3.63) | |

| Assertion | 14.86 (3.90) | 13.99 (3.79) | 14.18 (4.03) | 13.55 (4.00) | |

| Responsibility | 16.33 (3.55) | 16.31 (3.32) | 16.02 (3.66) | 16.20 (3.42) | |

| Empathy | 14.63 (3.14) | 14.39 (3.08) | 14.25 (3.27) | 14.14 (3.18) | |

| Engagement | 15.98 (3.68) | 15.57 (3.87) | 15.49 (3.84) | 15.22 (3.84) | |

| Self-control | 12.02 (4.22) | 11.53 (4.03) | 11.77 (4.12) | 11.29 (4.07) | |

Note. SECCI = Social and Emotional Competence Change Index, SDQ = Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, SSIS = Social Skills Improvement System.

Table 3.

Hierarchical linear model of the impact of PATHS on teacher ratings of changes in social–emotional competence (SECCI).

|

β0ij = − 0.26 (0.16) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Co-efficient β | SE | |

| School | 0.12 (12.5%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.04 |

| Group (if PATHS) | 0.47⁎⁎ | 0.15 |

| FSM | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| EAL | − 0.01 | 0.00 |

| SEL universal change | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| SEL targeted change | − 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Pupil | 0.83 (87.5%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.02 |

| Gender (if female) | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| FSM (if yes) | − 0.08⁎ | 0.04 |

| − 2 ∗ Loglikelihood = 8350.59 | ||

| X2(df = 7, N = 3123) = 1292.48⁎⁎⁎ | ||

Note. FSM = proportion of pupils eligible for free school meals, EAL = proportion of pupils with English as an additional language, SEL = social emotional learning.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 4.

Hierarchical linear models of the impact of PATHS on change in teacher perceptions of children's mental health (SDQ).

| a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional symptoms |

Conduct problems |

Hyperactivity |

||||

|

β0ij = − 0.30 (0.05) |

β0ij = − 0.35 (0.04) |

β0ij = − 0.26 (0.04) |

||||

| Co-efficient β | SE | Co-efficient β | SE | Co-efficient β | SE | |

| School | 0.01 (1.6%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.00 | 0.01 (1.5%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.00 | 0.00 (0.8%)⁎ | 0.00 |

| Group (if PATHS) | − 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.0 | 0.04 | − 0.05 | 0.0 |

| FSM % | − 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | − 0.00 | 0.00 |

| EAL % | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | − 0.00 | 0.00 |

| SEL universal change | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| SEL targeted change | − 0.00 | 0.0 | 0.003 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Pupil | 0.09 (15.2%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.01 | 0.10 (20.5%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.01 | 0.16 (32.6%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.01 |

| Gender (if female) | 0.08⁎⁎⁎ | 0.02 | − 0.21⁎⁎⁎ | 0.02 | − 0.29⁎⁎⁎ | 0.02 |

| FSM (if yes) | 0.17⁎⁎⁎ | 0.03 | 0.14⁎⁎⁎ | 0.02 | 0.18⁎⁎⁎ | 0.02 |

| Risk group (if at-risk) | 2.35⁎⁎⁎ | 0.06 | 2.28⁎⁎⁎ | 0.05 | 1.89⁎⁎⁎ | 0.04 |

| Time | 0.51 (83.1%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.01 | 0.37 (78%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.01 | 0.32 (66.5%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.01 |

| Time | 0.13⁎⁎⁎ | 0.03 | 0.18⁎⁎⁎ | 0.03 | 0.13⁎⁎⁎ | 0.03 |

| Interactions | ||||||

| Group ∗ Time (if PATHS, if post-test) | 0.10⁎⁎ | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Group ∗ Risk (if PATHS, if at-risk) | 0.21⁎⁎ | 0.08 | − 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Risk ∗ Time (if at-risk, if post-test) | − 1.65⁎⁎⁎ | 0.10 | − 1.27⁎⁎⁎ | 0.07 | − 0.72⁎⁎⁎ | 0.06 |

| Group ∗ Risk ∗ Time (if PATHS, if at risk, if post-test) | − 0.23⁎ | 0.12 | 0.26⁎⁎ | 0.09 | − 0.04 | 0.07 |

| − 2 ∗ Loglikelihood = 15,187.39 | − 2 ∗ Loglikelihood = 13,478.13 | − 2 ∗ Loglikelihood = 13,325.31 | ||||

| X2(df = 13, N = 6535) = 7397.70⁎⁎⁎ | X2(df = 13, N = 6535) = 8414.24⁎⁎⁎ | X2(df = 13, N = 6535) = 7997.30⁎⁎⁎ | ||||

| b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer problems |

Pro-social |

Total difficulties |

||||

|

β0ij = − 0.26 (0.05) |

β0ij = 0.19 (0.05) |

β0ij = − 0.32 (0.05) |

||||

| Co-efficient β | SE | Co-efficient β | SE | Co-efficient β | SE | |

| School | 0.01 (1.2%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.00 | 0.01 (1.5%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.00 | 0.01 (1.9%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.00 |

| Group (if PATHS) | − 0.10⁎ | 0.04 | 0.11⁎ | 0.04 | − 0.03 | 0.05 |

| FSM % | − 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | − 0.00 | 0.00 |

| EAL % | 0.00 | 0.00 | − 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Other SEL universal change | − 0.01 | 0.1 | 0.02⁎⁎ | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Other SEL targeted change | 0.00 | 0.01 | − 0.01 | 0.01 | − 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Pupil | 0.10 (17%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.01 | 0.10 (18.9%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.01 | 0.14 (27.4%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.01 |

| Gender (if female) | − 0.05⁎⁎⁎ | 0.02 | 0.36⁎⁎⁎ | 0.02 | − 0.21⁎⁎⁎ | 0.02 |

| FSM (if yes) | 0.15⁎⁎⁎ | 0.03 | − 0.14⁎⁎⁎ | 0.02 | 0.18⁎⁎⁎ | 0.02 |

| Risk group (if at-risk) | 2.34⁎⁎⁎ | 0.06 | − 1.72⁎⁎⁎ | 0.04 | 1.86⁎⁎⁎ | 0.05 |

| Time | 0.50 (81.9%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.01 | 0.42 (79.5%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.01 | 0.37 (70.7%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.01 |

| Time | 0.15⁎⁎⁎ | 0.03 | − 0.31⁎⁎⁎ | 0.03 | 0.17⁎⁎⁎ | 0.03 |

| Interactions | ||||||

| Group ∗ Time (if PATHS, if post-test) | 0.07⁎ | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| Group ∗ Risk (if PATHS, if at-risk) | 0.19⁎ | 0.08 | − 0.19⁎⁎⁎ | 0.06 | 0.10⁎ | 0.06 |

| Risk ∗ Time (if at-risk, if post-test) | − 1.59⁎⁎⁎ | 0.10 | 1.00⁎⁎⁎ | 0.06 | − 0.95⁎⁎⁎ | 0.06 |

| Group ∗ Risk ∗ Time (if PATHS, if at risk, if post-test) | − 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.16⁎ | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.08 |

| − 2 ∗ Loglikelihood = 15,157.41 | − 2 ∗ Loglikelihood = 14,275.28 | − 2 ∗ Loglikelihood = 13,982.28 | ||||

| X2(df = 13, N = 6535) = 7310.14⁎⁎⁎ | X2(df = 13, N = 6535) = 7877.16⁎⁎⁎ | X2(df = 13, N = 6535) = 7795.17⁎⁎⁎ | ||||

Note. FSM = proportion of pupils eligible for free school meals, EAL = proportion of pupils with English as an additional language, SEL = social emotional learning.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 5.

Hierarchical linear models of the impact of PATHS on change in children's perceptions of their social–emotional competence (SSIS).

| a | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total |

Communication |

Cooperation |

Assertion |

|||||

|

β0ij = − 0.10 (0.07) |

β0ij = 0.09 (0.05) |

β0ij = 0.06 (0.04) |

β0ij = 0.10 (0.06) |

|||||

| Co-efficient β | SE | Co-efficient β | SE | Co-efficient β | SE | Co-efficient β | SE | |

| School | 0.02 (2.1%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.01 | 0.01 (1%)⁎ | 0.00 | 0.00 (0.5%) | 0.00 | 0.02 (2%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.01 |

| Group (if PATHS) | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.05 |

| FSM | − 0.00 | 0.00 | − 0.00 | 0.00 | − 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00⁎⁎ | 0.00 |

| EAL | − 0.00 | 0.00 | − 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | − 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Other SEL universal change | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Other SEL targeted change | − 0.00 | 0.01 | − 0.01 | 0.01 | − 0.00 | 0.00 | − 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Pupil | 0.30 (26.3%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.02 | 0.14 (19.9%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.01 | 0.14 (22%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.01 | 0.14 (18.3%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.01 |

| Gender (if female) | 0.43⁎⁎⁎ | 0.03 | 0.36⁎⁎⁎ | 0.02 | 0.45⁎⁎⁎ | 0.02 | 0.27⁎⁎⁎ | 0.02 |

| FSM (if yes) | − 0.14⁎⁎⁎ | 0.03 | − 0.06⁎⁎⁎ | 0.03 | − 0.11⁎⁎⁎ | 0.03 | − 0.05⁎ | 0.03 |

| Risk group (if at-risk) | − 0.35⁎⁎⁎ | 0.08 | − 2.46⁎⁎⁎ | 0.07 | − 2.23⁎⁎⁎ | 0.06 | − 1.91⁎⁎⁎ | 0.07 |

| Time | 0.62 (71.6%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.02 | 0.56 (79.1%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.01 | 0.49 (77.5%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.01 | 0.60 (79.8%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.02 |

| Time | − 0.04 | 0.03 | − 0.21⁎⁎⁎ | 0.03 | − 0.19⁎⁎⁎ | 0.03 | − 0.16⁎⁎⁎ | 0.03 |

| Interactions | ||||||||

| Group ∗ Time (if PATHS, if post-test) | − 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | − 0.01 | 0.04 | − 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Group ∗ Risk (if PATHS, if at-risk) | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.10 | − 0.02 | 0.09 | − 0.11 | 0.10 |

| Risk ∗ Time (if at-risk, if post-test) | 0.07 | 0.11 | 2.00⁎⁎⁎ | 0.10 | 1.56⁎⁎⁎ | 0.09 | 1.44⁎⁎⁎ | 0.09 |

| Group ∗ Risk ∗ Time (if PATHS, if at risk, if post-test) | 0.07 | 0.4 | − 0.18 | 0.14 | − 0.27⁎⁎⁎ | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.13 |

| − 2 ∗ Loglikelihood = 17,196.05 | − 2 ∗ Loglikelihood = 16,414.93 | − 2 ∗ Loglikelihood = 15,686.28 | − 2 ∗ Loglikelihood = 16,804.77 | |||||

| X2(df = 13, N = 6332) = 5733.92⁎⁎⁎ | X2(df = 13, N = 6666) = 7108.68⁎⁎⁎ | X2(df = 13, N = 6663) = 7569.44⁎⁎⁎ | X2(df = 13, N = 6644) = 6665.46⁎⁎⁎ | |||||

| b | ||||||||

| Responsibility |

Empathy |

Engagement |

Self-control |

|||||

|

β0ij = 0.15 (0.05) |

β0ij = 0.04 (0.04) |

β0ij = 0.19 (0.44) |

β0ij = 0.12 (0.05) |

|||||

| Co-efficient β | SE | Co-efficient β | SE | Co-efficient β | SE | Co-efficient β | SE | |

| School | 0.01 (1.2%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.00 | 0.00 (0.6%)⁎ | 0.00 | 0.01 (0.7%)⁎ | 0.00 | 0.01 (1.3%)⁎⁎ | 0.00 |

| Group (if PATHS) | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.05 |

| FSM | − 0.00 | 0.00 | − 0.00⁎ | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | − 0.00 | 0.00 |

| EAL | − 0.00 | 0.00 | − 0.00 | 0.01 | − 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Other SEL universal change | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Other SEL targeted change | − 0.01 | 0.01 | − 0.00 | 0.00 | − 0.00 | 0.01 | − 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Pupil | 0.14 (21.1%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.01 | 0.14 (19.9%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.01 | 0.13 (18.3%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.01 | 0.12 (16.5%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.01 |

| Gender (if male) | 0.37⁎⁎⁎ | 0.02 | 0.45⁎⁎⁎ | 0.02 | 0.13⁎⁎⁎ | 0.02 | 0.25⁎⁎⁎ | 0.02 |

| FSM (if yes) | − 0.14⁎⁎⁎ | 0.03 | − 0.03⁎⁎⁎ | 0.03 | − 0.04⁎⁎⁎ | 0.03 | − 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Risk group (if at-risk) | − 2.04⁎⁎⁎ | 0.06 | − 2.31⁎⁎⁎ | 0.07 | − 2.04⁎⁎⁎ | 0.06 | − 1.91⁎⁎⁎ | 0.06 |

| Time | 0.52 (77.7%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.01 | 0.56 (79.6%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.01 | 0.58 (81%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.02 | 0.59 (82.2%)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.02 |

| Time | − 0.19⁎⁎⁎ | 0.03 | − 0.18⁎⁎⁎ | 0.03 | − 0.20⁎⁎⁎ | 0.03 | − 0.19⁎⁎⁎ | 0.03 |

| Interactions | ||||||||

| Group ∗ Time (if PATHS, if post-test) | − 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 | − 0.00 | 0.04 |

| Group ∗ Risk (if PATHS, if at-risk) | − 0.07 | 0.09 | − 0.12 | 0.10 | − 0.10 | 0.09 | − 0.09 | 0.09 |

| Risk ∗ Time (if at-risk, if post-test) | 1.41⁎⁎⁎ | 0.09 | 1.78⁎⁎⁎ | 0.10 | 1.52⁎⁎⁎ | 0.09 | 1.29 | 0.09 |

| Group ∗ Risk ∗ Time (if PATHS, if at risk, if post-test) | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.4 | 0.14 | 0.19⁎⁎⁎⁎ | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.12 |

| − 2 ∗ Loglikelihood = 15,976.30 | − 2 ∗ Loglikelihood = 16,418.47 | − 2 ∗ Loglikelihood = 16,553.91 | − 2 ∗ Loglikelihood = 16,484.03 | |||||

| X2(df = 13, N = 6650) = 7355.85⁎⁎⁎ | X2(df = 13, N = 6674) = 7140.03⁎⁎⁎ | X2(df = 13, N = 6642) = 7038.10⁎⁎⁎ | X2(df = 13, N = 6645) = 6995.06⁎⁎⁎ | |||||

Note. FSM = proportion of pupils eligible for free school meals, EAL = proportion of pupils with English as an additional language, SEL = social emotional learning.

Note. FSM = free school meals, EAL = English as an additional language, SEL = social emotional learning. Group denotes “if PATHS”.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

p < .10.

2.6. Measures

Outcomes were collected by teacher informant-report and child self-report surveys administered online by researchers at baseline and 24-month follow-up. The primary outcomes were changes in children's social–emotional competence, assessed via the Social Skills Improvement System subscales (SSIS), the Social and Emotional Competence Change Index (SECCI), and Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) Pro-Social Behavior subscale (detailed below), and mental health difficulties, which were assessed via the SDQ Emotional Symptoms, Conduct Problems, Inattention/Hyperactivity, and Peer Problems subscales (detailed below) during this period.

2.6.1. Child self-report version of the Social Skills Improvement System (SSIS; Gresham & Elliot, 2008)

Child-rated social–emotional competence was assessed using the 46-item social skills domain of the self-report version of the SSIS (Gresham & Elliot, 2008). The SSIS provides an index of children's Communication (e.g., “I say ‘please’ when I ask for things”), Cooperation (e.g., “I pay attention when others present their ideas”), Assertion (e.g., “I ask for information when I need it”), Responsibility (e.g., “I'm careful when I use things that aren't mine”), Empathy (e.g., “I try to forgive others when they say ‘sorry’”), Engagement (e.g., “I get along with other children”), and Self-Control (e.g., “I stay calm when I am teased”), in addition to a composite Social Skills score. The scale follows a Likert response format in which the child reads a statement and indicates their level of agreement on a four-point scale (never, sometimes, often, always). The SSIS rating scale is psychometrically sound, with good reliability (internal: co-efficients range from 0.72–0.95; test–retest: co-efficients range from 0.72–0.92) and strong validity (factorial: established through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA); convergent: correlates with a range of similar instruments; discriminative: discriminates between clinical and non-clinical samples). Furthermore, the development and subsequent refinement of the SSIS utilized Item Response Theory (Gresham and Elliot, 2008, Humphrey et al., 2011). Internal consistency of this instrument in the current study ranged from α = 0.67 (Assertion and Responsibility, baseline) to α = 0.83 (Self-Control, follow-up). Risk status was ascertained by applying the behavior levels corresponding to subscale raw scores published by the measure developer. For example, scores on the Empathy scale range from 0 to 18; children scoring 0–10 (females) and 0–8 (males) are classed as below average and were therefore deemed to be at-risk for the purpose of analysis.

2.6.2. Teacher informant-report version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 1997)

Teacher-rated mental health was assessed using the 25-item SDQ, which provides a measure of children's Emotional Symptoms (e.g., “has many worries”), Conduct Problems (e.g., “often fights with other children”), Hyperactivity/Inattention (e.g., “is constantly fidgeting and squirming”), Peer Problems (e.g., “is picked on or bullied by other children”), and Pro-Social Behavior (e.g., “is considerate of other people's feelings”), in addition to a composite Total Difficulties score made up of the four difficulties subscales. It is the most widely used outcome measure of its type in the UK (Johnston & Gowers, 2005). The SDQ follows a Likert response format in which raters read a statement and indicate their level of agreement on a three-point scale (not true, somewhat true, certainly true). The measure has sound psychometric properties, with evidence of both reliability (internal: coefficients range from 0.57–0.87; test–retest: coefficients range from 0.61–0.80) and validity (factorial: established through exploratory factor analysis [EFA]; convergent: correlates with a range of similar instruments; predictive: strongly predictive of independently diagnosed psychiatric disorders; Goodman and Scott, 1999, Goodman, 2001). Internal consistency of this instrument in the current study ranged from α = 0.68 (Peer Problems, baseline) to α = 0.90 (Hyperactivity/Inattention, baseline). Risk status was ascertained by applying the clinical cut-points published by the measure developer for each outcome variable. For example, Conduct Problems is scored from 0 to 10. For children aged 4–17, a score of 3 receives the borderline classification, while 4–10 receives the abnormal classification. Children scoring in the borderline or abnormal range for a given subscale were deemed to be at-risk for the purpose of analysis.

2.6.3. Teacher informant-report version of the Social and Emotional Competence Change Index (SECCI)

Teacher ratings of changes in children's social–emotional competence were assessed using the five-item SECCI, which was derived from the PATHS program evaluation tools (Evidence-based Prevention and Intervention Supports (EPIS) Center, 2014). The SECCI follows a Likert response format in which raters indicate the degree of change they have observed in a child (an example item is, “The pupil's ability to stop and calm down e.g., when angry, excited or upset”) over a specified period using on a five-point scale (much worse, a little worse, no change, a little improved, much improved). Internal consistency of this instrument in the current study was α = 0.93.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Outcomes were assessed using the intention to treat (ITT) method. ITT involves the analysis of data for all participants who have been randomly assigned to one of the treatment conditions in a RCT, regardless of their characteristics and whether or not they actually received it. ITT analysis is considered to be the most rigorous and robust approach to analyzing trial outcomes as it gives an unbiased estimate of treatment effect (Gupta, 2011). However, given the theoretical and empirical precedence of differential program benefits in interventions like PATHS, we also incorporated sub-group analyses (Petticrew et al., 2012) for children deemed to be at-risk. Consistent with prior literature (e.g., Berry et al., 2015), ITT and subgroup analyses were conducted on the subscales of each outcome measure in addition to their composites (e.g., total difficulties on the SDQ; social skills on the SSIS). This was done in order to guard against the increased likelihood of a Type II error associated with focusing solely on composite scores (e.g., masking of intervention effects in composite variables), while also affording increased precision in the determination of intervention effects.

In view of the hierarchical and clustered nature of the study dataset, we used hierarchical linear modeling in MLWin 2.32. For the SSIS and SDQ outcome data each model was fitted with three levels (school, child, time). Treatment allocation group (PATHS versus control), minimization variables (school level EAL and FSM), and reported changes in other SEL practice at both universal and targeted levels were entered as explanatory variables at the school level. Baseline risk status (normal versus at-risk) was entered as an explanatory variable at the child level, as was sex and FSM eligibility, given their well-documented association with mental health outcomes in childhood (Green, McGinnity, Meltzer, Ford, & Goodman, 2005). For the SECCI outcome data the model was fitted with two levels (school, child), with treatment allocation group (PATHS versus control), minimization variables (school level EAL and FSM), and reported changes in other SEL practice at both universal and targeted levels entered as explanatory variables at the school level, and sex and FSM eligibility entered as co-variates at the child level.

A series of cross-level interaction terms were specified using dummy coding (e.g., 0 = control, 1 = PATHS; 0 = not at risk, 1 = at-risk). The core terms were Group*Time (to test for primary effects) and Group ∗ Risk ∗ Time (to test for secondary effects). These interaction terms were set such that the co-efficient (and accompanying standard error and p value) produced in a given model represented the estimate of intervention effect. For primary effects, this was specified as “If PATHS, at follow-up”, and for secondary effects, “If PATHS, if at-risk, at follow-up.”

Outcome variable data was standardized (e.g., converted to z-scores) prior to analysis. In addition to mean-centering the data, this procedure also facilitates the interpretation of treatment effects, as the coefficient associated with treatment allocation in each model is essentially the same as Cohen's d (e.g., the difference in scores between children in the PATHS and usual provision groups divided by the standard deviation of scores). This effectively produces an ES estimate that accounts for all other variables included in the model, increasing precision and rigor (Bierman et al., 2014).

3. Results

Assessment of balance on key observables between the trial groups at baseline revealed negligible differences — with only the Pro-Social Behavior subscale of the SDQ exhibiting a difference of greater than d = 0.1 (see Table 1). After accounting for data clustering and multiple comparisons, there were no statistically significant differences between the two trial groups at baseline on any outcome measure.

Descriptive and inferential statistics pertaining to the testing of our study hypotheses are presented in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5. In terms of Hypothesis 1 (improvements in social–emotional competence), our ITT analyses demonstrated that PATHS led to a statistically significant increase in teachers' perceptions of change in children's social–emotional competence, d = 0.47, 95% CI [0.97, 0.76], p = .01 (see Table 3). The associated ES was on the cusp of “medium” using Cohen's (1992) classification, and in terms of practical significance was equivalent to an 18-percentile point increase in social–emotional competence as a result of allocation to the intervention group of the trial (using the U3 ES index; Durlak, 2009). No statistically significant primary intervention effects were identified in relation to our other measures of social–emotional competence (SSIS composite and subscales, see Table 5a and b; SDQ Pro-Social subscale, see Table 4b) at the ITT level. Our analyses therefore provide partial support for Hypothesis 1.

In relation to Hypothesis 2 (reductions in mental health difficulties), our ITT analyses identified no statistically significant primary effects of PATHS on Emotional Symptoms, Hyperactivity/Inattention, or Conduct Problems at the ITT level. However, a statistically significant primary effect favoring the control group was identified in relation to both Peer Problems, d = 0.07, 95% CI [− 0.00, 0.15], p = .03 (see Table 4b), and Emotional Symptoms, d = 0.10, 95% CI [0.02, 0.18], p = .01 (see Table 4a). The associated ES were extremely small, being equivalent to 3 (Peer Problems) and 4 (Emotional Symptoms) percentile point reductions in difficulties as a result of allocation to the control group of the trial. Our analyses therefore failed to provide support for Hypothesis 2.

With regard to Hypothesis 3a (secondary effects – social–emotional competence), our subgroup analyses demonstrated that PATHS led to statistically significant increases in Pro-Social Behavior, d = 0.16, 95% CI [− 0.00, 0.33], p = .03 (see Table 4b) and (marginally) Engagement, d = 0.19, 95% CI [− 0.05, 0.43], p = .06 (see Table 5b), among children classified as at-risk at baseline. In relation to the former, the intervention ES was extremely small, equivalent to a 6-percentile point increase in Pro-Social Behavior of at-risk children as a result of allocation to the intervention group of the trial. With regard to the latter, the intervention ES was on the cusp of Cohen's (1992) small designation, equivalent to an 8-percentile point increase in engagement of at-risk children as a result of allocation to the intervention group of the trial. However, a statistically significant secondary effect favoring the control group was identified in relation to Cooperation, d = − 0.27, 95% CI [− 0.50, − 0.04], p = .01 (see Table 5a). The associated ES was small, equivalent to a 10-percentile point increase in Cooperation of at-risk children as a result of allocation to the usual provision group of the trial. Our analyses therefore provide partial support for Hypothesis 3a.

Finally, with regard to Hypothesis 3b (secondary effects – mental health difficulties), our subgroup analyses demonstrated that PATHS led to a statistically significant reduction in Emotional Symptoms, d = − 0.23, 95% CI [− 0.46, 0.01], p = .03 (see Table 4a), among children classified as at-risk at baseline. The associated ES was small, equivalent to a 9-percentile point reduction in Emotional Symptoms among the at-risk subgroup as a result of allocation to the intervention group of the trial. However, a statistically significant secondary effect favoring the control group was identified in relation to conduct problems, d = 0.26, 95% CI [0.08, 0.43], p = .01 (see Table 4a), among at-risk children. The associated ES was small, equivalent to a 10-percentile point reduction in Conduct Problems among the at-risk subgroup as a result of allocation to the control group of the trial. Our analyses therefore provide partial support for Hypothesis 3b.

4. Discussion

Using a large, nationally representative sample, the results of this RCT demonstrate a robust primary effect of the PATHS curriculum in improving children's social–emotional competence. Our findings also highlight secondary effects of PATHS in reducing emotional symptoms and improving pro-social behavior and engagement among children classified as at-risk. However, there was also evidence of primary effects favoring the usual school provision group for peer problems and emotional symptoms, alongside secondary effects in relation to conduct problems and cooperation among at-risk children. Assessment of implementation through independent structured observations conducted in schools in the treatment group of the trial revealed high levels of intervention fidelity, quality, participant responsiveness and reach, but lower than expected dosage.

The primary and secondary intervention effects noted above are broadly consistent with the theoretical frameworks that informed the study (EPIS Center, 2014, Humphrey, 2013). To wit, SEL theory and the PATHS logic model posit that improved social–emotional competence in children confers resilience to the onset, maintenance or progression of mental health difficulties. Hence, PATHS produced a primary effect on social–emotional competence, with secondary effects in two domains that are likely to vary directly as a function of this (e.g., we could plausibly expect reductions in emotional symptoms among at-risk children as being brought about by improved competence in emotional regulation). The secondary intervention effect on emotional symptoms directly mirrors that of the aforementioned trial of PATHS in Birmingham, England (Berry et al., 2015, Little et al., 2012) which also found a significant positive impact of PATHS among children (albeit those aged 4–6 years old) classified as at-risk in relation to their elevated levels of emotional symptoms.

Observed effects were modest in all cases except for the primary effect on teacher-rated social–emotional competence. Using Cohen's U3 index (Durlak, 2009), percentile improvements for intervention effects ranged from 6% (secondary effect, pro-social behavior) to 18% (primary effect, social–emotional competence), indicating modest levels of practical significance overall (Durlak, 2009). The odds ratio for movement from the borderline/abnormal to normal range of SSIS and SDQ subscales associated with the various intervention effects outlined above peaked at 1.3 (for emotional symptoms), indicating moderate clinical significance. However, this is perhaps to be expected given the relatively low intensity of this universal intervention and the fact that by definition it was implemented with a largely healthy sample (Stallard et al., 2012). It is also noteworthy that the effects outlined above were achieved in the absence of assumed optimal dosage, a finding that is consistent with the implementation science evidence base (Durlak & DuPre, 2008) and some other studies of the PATHS curriculum (Berry et al., 2015, Faria et al., 2013).

Contrary to our initial predictions, there was also evidence that usual school provision was significantly more effective than PATHS in reducing emotional symptoms and peer problems in all children, and improving cooperation and reducing conduct problems among at-risk children. Interestingly, Berry et al. (2015) also found that usual provision was more effective than PATHS in reducing conduct problems,2 although in their study this was a primary rather than secondary effect. One explanation for our unexpected findings is that the increases in other SEL practice at both universal and targeted levels reported in the control group triggered these improved outcomes. In support of this view is the fact that the intervention that saw the largest growth in reported use among control schools was the Targeted Mental Health in Schools program (TaMHS; Humphrey, Barlow, Lendrum, & Wigelsworth, 2013). TaMHS has been shown to be efficacious in reducing behavior difficulties among at-risk children in primary schools (Deighton et al., 2015). However, we can confidently rule out this explanation, having controlled for changes in other SEL practice at both universal and targeted levels in both trial groups in our analyses. Put another way, the findings reported herein, whether favoring the PATHS or usual provision group, are after taking into account any changes in other SEL practice reported by schools during the trial. From an analytical standpoint, incorporating such data represents an advancement on the standard models used in the field because it allows a more accurate estimate of treatment effects (what Nelson, Cordray, Hulleman, Darrow, & Sommer, 2012, call the “achieved relative strength” of the intervention).

An alternative explanation is that PATHS displaced other, efficacious approaches. Although intervention schools reported stability in their other SEL practice, hours in the school day are necessarily fixed and so some displacement was inevitable; anecdotal evidence from our implementation and process evaluation suggests that PATHS was usually delivered in timetable slots typically allocated for PSHE (PATHS to Success Research Team, 2015). Unlike the increases in provision of interventions like TaMHS, there is a lack of clear evidence regarding the impact of PSHE on peer and/or conduct problems and so we can only speculate as to whether its displacement in PATHS schools was detrimental. A third explanation is that the negative effects on peer and conduct problems were a consequence of changes in teacher expectations of children's behavior brought about by participation in PATHS, e.g., over-reporting as a result of increased awareness (Berry et al., 2015). However, this seems unlikely given the increase in the use of TaMHS — which included a significant mental health awareness component - among schools in the usual school provision group of the trial. A final explanation is that the non-optimal dosage observed in the implementation of PATHS led to diminishing returns in more distal, behavioral outcomes. In a future paper we will model temporal relations among our trial outcomes with this hypothesis in mind. Ours is not the only universal school-based intervention trial to report possible negative effects on mental health (Stallard et al., 2012), and further investigation is required to examine these and other possible explanations such that the underpinning mechanisms are better understood.

Given the mixed findings of this RCT, it is worth briefly returning to the issue of cultural transferability of evidence-based interventions like PATHS to consider whether this may have feasibly influenced our outcomes. As noted earlier, the PATHS materials were subjected to a process of cultural adaptation by Barnardo's in order to maximize their goodness of fit to the cultural needs, values and expectations of the UK school system. Despite this, the qualitative aspect of our implementation and process evaluation did highlight dissatisfaction among some staff regarding the cultural adaptation process (e.g., “It's too Americanized… Some of the things in the booklet are very American”; PATHS to Success Research Team, 2015, p.23). However, we feel that it is unlikely that this created a significant barrier to implementation, as these views were by no means universal. Indeed, many teachers praised the intervention materials for their appropriateness. Furthermore, data from our structured observations showed that implementation was generally very good (see Method). Finally, the explanations given for the lack of optimal dosage did not appear to relate to issues of cultural incompatibility, but rather a lack of time in a very busy school timetable (PATHS to Success Research Team, 2015), something that will doubtlessly resonate with educators across many diverse cultures.

4.1. Strengths and limitations of the study

The current study has numerous strengths. We made use of a cluster-randomized design that would allow for claims of causality, and utilized a sample large and diverse enough for us to infer generalizability of effects. The trial was more than adequately powered to detect likely treatment effects of the PATHS program.3 Assessment of outcomes was theory-based. Furthermore, we attempted to optimize implementation effectiveness via training for implementers and provision of technical support and assistance by trained PATHS coaches, who were in turn supported by an accredited trainer from PSU. Consistent with school-based prevention theory and previous research, we utilized both ITT and sub-group analyses in order to assess both primary and secondary intervention effects. Additionally, the current study is among the first to control for changes in other SEL practice when modeling intervention outcomes (thus enabling assessment of the achieved relative strength of PATHS).

The trial sample was balanced on key observables and the school-level attrition rate was just 11%. Furthermore, comparison of schools that dropped out of the study with those that did not revealed no significant differences on any assessed school characteristics (e.g., size, attendance, attainment, and the proportions of children identified as having special educational needs, eligible for FSM, and speaking EAL). No major threats to validity were identified. Thus, the intervention is described in detail to allow for replication (Hoffmann et al., 2014). Although the research team is known to the program developer, they have no conflict of interest relating to PATHS and are independent evaluators. Contamination was not possible due to the cluster-randomized design and supply control of intervention materials by Barnardo's. Our outcome measurement protocol used established instruments (SSIS, SDQ) and included assessment of mental health, a distal outcome that cannot be considered “inherent to treatment”. Finally, although compensatory rivalry appeared to occur in the control group of the trial, our outcome analyses accounted for this.

However, participants were not blinded to treatment allocation, a limitation that is difficult (if not impossible) to circumvent in school-based trials (Stewart-Brown and Anthony, 2011, Sullivan, 2011). Additionally, with only two groups in the trial (PATHS versus control), a non-specific placebo effect cannot be completely ruled out, however unlikely this seems, especially in light of the findings that favored schools in the usual provision group of the trial. Finally, the increased internal validity afforded by the provision of training from PSU staff and technical support and assistance for schools in the intervention group arguably created a trade-off resulting in reduced external validity, given that this would not be routinely available to schools (Shucksmith, 2007). In line with accepted approaches to the evaluation of health interventions (Campbell, 2000), an important avenue for future research is therefore to consider the impact of PATHS and other SEL programs under true effectiveness (e.g., “real world”) conditions (Humphrey, 2013).

4.2. Mental health promotion in schools

The findings of this study are reported at a critical juncture in the on-going discussion regarding the role of schools in promoting children's mental health. In England, more than £250 million has been cut from mental health service budgets since 2011/12, with funding for children's mental health reduced by up to 94% in some areas (Cooper, 2014). With schools being left to “pick up the pieces” (O'Hara, 2014), the need for access to efficacious preventive approaches has never been greater. As previously noted, PATHS was recently recommended for wide-scale dissemination in UK primary schools (Allen, 2011). The findings from this trial continue the established pattern of inconsistent effects in independent trials of the program (e.g., Little et al., 2012, Ross et al., 2011), but provide important additional contributions in terms of examining its impact on outcomes for older children and also highlighting outcome domains where usual school provision may in fact be more efficacious. Thus, in light of the relatively small treatment effects observed and the unexpected findings that favored the control group, we do not feel fully able to endorse the call for PATHS to be scaled up in the UK, at least until further analyses that increase our understanding of these outcomes (e.g., to what extent did implementation variability moderate outcomes?) and place them in context (e.g., is PATHS cost-effective?) have been completed. These important questions will be addressed in future papers by our research team.

In spite of the increasingly central role played by schools in mental health promotion, current education policy in England often directly obstructs this, pushing schools to maximize academic attainment and ignore the broader health and wellbeing of their pupils (Bonell et al., 2014). The lower than expected dosage observed in our assessment of implementation at least in part reflects this. Interviews with class teachers revealed that they felt pressure to prioritize the core academic curriculum and often struggled to find space and time to implement PATHS to the specified frequency/regularity (PATHS to Success Research Team, 2015). Thus, while schools and teachers are typically willing and motivated to address children's mental health, they feel prevented from doing so by the government's imposition of an increasingly narrow view of the purpose and function of education.

The magnitude of the effects observed in the current study also serve as a salient reminder that universal SEL interventions are by no means a panacea, and should instead form part of a tiered approach to prevention that incorporates appropriate selective and targeted interventions in order to trigger more clinically and practically significant changes in outcomes. What this study has rigorously demonstrated is that using schools as a “first line of defense” can make a contribution – however modest – to improving social–emotional competence and some mental health outcomes for children.

ACTION EDITOR: Thijs Jochem.

Footnotes

The exact number of PATHS lessons varies slightly from year group to year group. Some year group curriculum packs also contain additional ‘extension’ lessons.

Berry et al. (2015) presented two versions of their analyses — the first with complete cases only, and the second using multiple imputation. The conduct problems effect referenced in this paper was found in the imputed data analysis.

The mean minimum detectable effect size (ES) for the SSIS was d = 0.15, based upon a pretest and demographic co-variates model (Hedges & Hedberg, 2007) involving 45 schools with approximately 100 children in each, a mean intra-cluster correlation co-efficient (ICC) of 0.03 (after accounting for minimization variables at the cluster level and sex and FSM eligibility at the child level), an average pretest-posttest correlation of 0.31, and Power and Alpha set to 0.8 and 0.05 respectively. For the SECCI, the nature of the instrument meant that a post-test only design (Gorard, 2013) was utilized. The ICC was higher at 0.2, meaning that the study was powered to detect an ES of d = 0.39 or greater. Relative to mean ESs of 0.57 (Durlak et al., 2011) to 0.7 (Sklad et al., 2012) for social–emotional competence reported in the literature, this meant that the current trial was more than adequately powered to detect likely treatment effects of the PATHS program.

For the SDQ, the mean minimum detectable effect size was d = 0.15, based upon the same basic assumptions reported above, an ICC of 0.04, and an average pre-test-post-test correlation of 0.44. This is consistent with the aforementioned meta-analyses, which reported ESs in the 0.19 (Sklad et al., 2012) to 0.23 (Durlak et al., 2011) range for mental health outcomes of universal school-based SEL interventions.

References

- Allen G. H. M. Government; London: 2011. Early intervention: The next steps. [Google Scholar]

- Arda T.B., Ocak S. Social; competence and promoting alternative thinkings strategies — PATHS preschool curriculum. Educational Sciences: Theory & Pratice. 2012;12:2691–2698. [Google Scholar]

- Belfer M.L. Child and adolescent mental disorders: The magnitude of the problem across the globe. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2008;49:226–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry V., Axford N., Blower S., Taylor R.S., Edwards R.T., Tobin K.…Bywater T. The effectiveness and micro-costing analysis of a universal, school-based, social–emotional learning programme in the UK: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. School Mental Health. 2015 (Online First) [Google Scholar]

- Bierman K.L., Nix R.L., Heinrichs B.S., Domitrovich C.E., Gest S.D., Welsh J.A., Gill S. Effects of Head Start REDI on children's outcomes 1 year later in different kindergarten contexts. Child Development. 2014;85:140–159. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonell C., Humphrey N., Fletcher A., Moore L., Anderson R., Campbell R. Why schools should promote students' health and wellbeing. BMJ (Clinical Research Edition) 2014;348:g3078. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M. Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. BMJ. 2000;321:694–696. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7262.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro F.G., Barrera M., Martinez C.R. The cultural adaptation of prevention interventions: Resolving tensions between fidelity and fit. Prevention Science. 2004;5:41–45. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000013980.12412.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Mental Health . Center for Mental Health; London: 2010. The economic and social costs of mental health problems in 2009/10. [Google Scholar]

- Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence Blueprints for healthy youth development. 2016. http://www.blueprintprograms.com Retrived from.

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group The effects of a multiyear universal social–emotional learning program: The role of student and school characteristics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:156–168. doi: 10.1037/a0018607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C. The Independent; 2014, August 20. Children's mental healthcare in crisis, Care Minister Norman Lamb admits. (Retrieved from http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/health-news/exclusive-childrens-mental-healthcare-in-crisis-care-minister-norman-lamb-admits-9679098.html) [Google Scholar]

- Crean H.F., Johnson D.B. Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies (PATHS) and elementary school aged children's aggression: Results from a cluster randomized trial. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2013;52:56–72. doi: 10.1007/s10464-013-9576-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis C., Norgate R. An evaluation of the Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies curriculum at key stage 1. Educational Psychology in Practice. 2007;23:33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Davies S.C. Department of Health; London: 2012. Our children deserve better: Prevention pays (annual report of the Chief Medical Officer 2012) [Google Scholar]

- Deighton J., Humphrey N., Wolpert M., Patalay P., Belsky J., Vostanis P. An evaluation of the implementation and impact of England's mandated school-based mental health initiative in elementary schools. School Psychology Review. 2015;44:117–139. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education . Department for Education; London: 2010. Schools, pupils and their characteristics. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education . Department for Education; London: 2012. Children with special educational needs: An analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education . Department for Education; London: 2013. National curriculum assessments at key stage 2: 2012 to 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education . Department for Education; London: 2014. Mental health and behaviour in schools. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education . Department for Education; London: 2014. Pupil absence in schools in England: 2012 to 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Domitrovich C.E., Cortes R.C., Greenberg M.T. Improving young children's social and emotional competence: A randomized trial of the preschool “PATHS” curriculum. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2007;28:67–91. doi: 10.1007/s10935-007-0081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlak J.A. How to select, calculate, and interpret effect sizes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009;34:917–928. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlak J.A., DuPre E.P. Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41:327–350. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlak J.A., Weissberg R.P., Dymnicki A.B., Taylor R.D., Schellinger K.B. The impact of enhancing students' social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development. 2011;82:405–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorsky M., Girio-Herrera E., Owens J.S. School-based screening for mental health in early childhood. In: Weist M.D., editor. Hadnbook of school mental health. Springer; New York, NY: 2014. pp. 297–310. [Google Scholar]

- Eisner M. No effects in independent prevention trials: Can we reject the cynical view? Journal of Experimental Criminology. 2009;5:163–183. [Google Scholar]

- EPIS Center Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies. 2014. http://www.episcenter.psu.edu/ebp/altthinking Retrieved from.

- Evans R., Scourfield J., Murphy S. The unintended consequences of targeting: Young people's lived experiences of social and emotional learning INTERVENTIONS. British Educational Research Journal. 2014;41:381–397. [Google Scholar]

- Faria A.M., Kendziora K., Brown L., O'Brien B., Osher D. American Institutes for Research; Washington, DC: 2013. PATHS implementation and outcome study in the Cleveland Metropolitan School District: Final report. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38:581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:1337–1345. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R., Scott S. Comparing the SDQ and the CBCL: Is small beautiful? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1999;27:17–24. doi: 10.1023/a:1022658222914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman A., Joshi H., Nasim B., Tyler C. Early Intervention Foundation; London: 2015. Social and emotional skills in childhood and their long-term effects on adult life. [Google Scholar]

- Goossens F., Gooren E., de Castro B.O., Overveld K.V., Buijs G., Monshouwer K.…Paulussen T. Implementation of PATHS through Dutch municipal health services: A quasi-experiment. International Journal of Conflict and Violence. 2012, November 8;6:234–248. [Google Scholar]