Abstract

Objective

To assess whether the delay to care among Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) personnel who sought care for a mental disorder changed over time and in association with CAF mental health system augmentations.

Design

A stratified, random sample (n=2014) was selected for study from an Afghanistan-deployed cohort (N=30 513) and the 415 (weighted N=4108) individuals diagnosed with an Afghanistan service-related mental disorder were further assessed. Diagnosis-related data were abstracted from medical records (22 June 2010 to 30 May 2011). Other data were extracted from administrative databases. Delay to care was assessed across five mental health system eras: 2002/2004, 2005/2006, 2007, 2008 and 2009/2010. Weighted Cox proportional hazards regression assessed the association between era, handled as a time-dependent covariate, and the outcome while controlling for a broad range of potential confounders (ie, sociodemographic, military and clinical characteristics). Taylor series linearisation methods and sample design weights were applied in generating descriptive and regression analysis statistics.

Primary outcome

The outcome was the delay to mental healthcare, defined as the latency from most recent Afghanistan deployment return date to diagnosis date, among individuals with an Afghanistan service-related mental disorder diagnosis.

Results

Mean delay to care was 551 days (95% CI 501 to 602); the median was 400 days. Delay to care decreased in subsequent eras relative to 2002/2004; however, only the most recent era (2009/2010) was statistically significant (adjusted HR (aHR): 3.01 (95% CI 1.91 to 4.73)). Men, operations support occupations, higher ranks, non-musculoskeletal comorbidities and fewer years of military service were also independently associated with longer delays to care.

Conclusions

CAF mental health system changes were associated with reduced delays to mental healthcare. Further evaluation research is needed to identify the key system changes that were most impactful.

Keywords: MENTAL HEALTH, military, delay to care, treatment seeking

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Reducing delays to mental healthcare in military (and civilian) populations has been targeted by numerous programmes attempting to reduce barriers to care and this study demonstrated a reduction in the delay to care over time among Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) personnel with an apparent mental healthcare need.

This study used an objective measure of delay to care from an apparent need, as indicated by a disorder that resulted from an attributed deployment exposure, to a concrete measure of care being received for the apparent need, as defined by the specific service-related diagnosis.

The delay to mental healthcare measured in this study was a sum of the delay from individuals' apparent need for care to their decision to seek it and the administrative delay or wait time imposed before care is actually received.

The era variable used in this observational study was a proxy for mental health system augmentations that were made over time in the CAF and while beneficial reductions in delay to care were associated with the more recent system augmentations, the beneficial reductions cannot be definitively attributed to these augmentations.

Introduction

The unique experiences encountered by military personnel on deployment can create a vulnerability to a number of health problems; a fraction will develop mental health problems and will have a need for mental health services. Since 2001, millions of military personnel have deployed to the conflicts in Southwest Asia and many have returned with mental health problems.1 2 In Canada, 13.5% of personnel who deployed in support of the mission in Afghanistan were diagnosed with a service-related mental disorder within 4 years after their return.2 For those in high-threat locations, estimated rates approach 30% after 7 years.2

Previous studies on military personnel indicate that many with a mental disorder do not seek out needed mental health services and only a small proportion do so in a timely manner.3 4 Barriers to timely mental healthcare seeking in military and veteran populations have been identified.5 6 These barriers can include a perceived external, and often internalised stigma associated with admitting psychological difficulties, an inability to recognise the need for care, restrictive personal beliefs about mental disorders and associated treatments, a concern over potential negative career consequences and structural barriers to care such as lengthy wait times and the level of difficulty associated with treatment access.5 6 Additionally, some authors identify a number of facilitators to mental healthcare seeking, features that may directly have a positive influence on barriers to care seeking, such as the presence of a supportive organisational climate, social support facilitators and systems that educate on mental health and promote treatment seeking.6 Reported delays to mental healthcare among civilian populations also tend to be variable, and can be substantial,7 8 and are similarly susceptible to attitudinal and structural barriers to care.8–11

The Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) and other military organisations have adjusted their mental health systems over the past 15 years in an effort to minimise the impact of barriers to mental healthcare.12–14 In the CAF, the number of mental health providers has more than doubled. Five multidisciplinary Operational Trauma and Stress Support Centres were established in 1999 to provide standardised assessments and treatments for service-related mental health problems; an additional two were established in 2010. Lower levels of stigma and other barriers to care have been reported in comparison with other military organisations,15 possibly resulting from de-stigmatisation efforts. The CAF's resilience and mental health training programme was implemented in January of 2008 with a focus on educating members on mental illness awareness and stigma reduction. In September of 2009, this programme was further integrated across the deployment cycle and included instruction with an additional emphasis on prevention and psychological resilience.16 In-depth postdeployment mental health screening was introduced in 2002 and became fully implemented within the CAF in August of 2004.16 The past decade has also seen subtle changes in the application of medical policy that made it easier for personnel who recover from mental disorders to remain in uniform, reducing a potential career-related barrier to care seeking. Moreover, while some researchers have found that self-reported stigma and other barriers to care have reduced over time,17 18 little is known on whether these changes translate into reductions in delay to care.

This study investigates changes in the delay to mental healthcare in CAF personnel over a period of multifaceted, evolutionary reinforcement to its mental health system.

Methods

Study population and setting

The study population consisted of a retrospective cohort of CAF personnel (N=30 513) who initiated a deployment outside of North America and Europe in support of the Afghanistan mission from 1 October 2001 through 31 December 2008.

A weighted, stratified random sample of 2045 individuals was identified; medical records were reviewed for 2014 of these individuals and inaccessible for 31. The sampling strata were defined by deployment location and mental health services use, strata relevant to the parent study's primary objective.2 An earlier analysis on this cohort estimated that, after a mean follow-up of ∼4 years, 13.5% of the cohort (weighted N=4108) were diagnosed with a mental disorder that a clinician attributed to an Afghanistan deployment and the data further suggested that the cumulative incidence of such mental disorders would level off at ∼20% when the mean follow-up approached 10 years.2 Thus, an additional 6.5% of the cohort is expected to be diagnosed with an Afghanistan service-related mental disorder after an additional 6 years of poststudy follow-up and these individuals have not yet received mental healthcare, and thus, were not part of the current assessment.

The current study was limited to individuals with a mental disorder diagnosis that a clinician attributed to an Afghanistan deployment (sampled n=415; weighted N=4108); diagnoses were identified over a median of 1364 days (mean: 1525 days; range: 1–3344 days), from deployment return to the earlier of chart review date, and when present, mental disorder diagnosis date.

Data collection

As discussed elsewhere,2 deployment details came from administrative databases. Mental disorder diagnoses, diagnosis date, mental disorder history and clinician-identified attributions to service were abstracted from medical records over the period of 22 June 2010 to 30 May 2011; marital status and the presence of live-in dependents were also identified from the chart review, relative to the diagnosis date. Data on sociodemographic variables and military characteristics came from administrative databases (extract date: 15 December 2012). Data linkages were based on service number, a unique CAF-specific personal identifier.

Outcome definition

The outcome was delay to care, measured from individuals' most recent Afghanistan deployment return date, a proxy for symptom onset, to their mental disorder diagnosis date. We excluded 93 individuals (unweighted) whose mental disorder was unrelated to their prior Afghanistan deployment because a comparable proxy for symptom onset date was unavailable.

This measure of delay to care is a sum of the delay from individuals' apparent need for care to their decision to seek it and the administrative delay or wait time imposed before care is actually received, among those who ultimately sought and received care. Thus, it incorporates both individual factors that may impact decision-making around the need for care and the environmental or structural factors that may facilitate care seeking. The enhancements made to the CAFs mental health system have, over time, focused on both of these areas in an attempt to reduce overall delays to mental healthcare.

Covariate of interest

The primary covariate of interest was mental health system era (henceforth, ‘era’), assessed over the period from deployment return to mental disorder diagnosis and used as a proxy for enhancements to the CAF mental health system. Era was categorised into the following periods: 28 February 2002 to 31 December 2004 (2002/2004), 01 January 2005 to 31 December 2006 (2005/2006), 01 January 2007 to 31 December 2007 (2007), 01 January 2008 to 31 December 2008 (2008) and 01 January 2009 to 24 January 2011 (2009/2010). This categorisation was based on the distribution of data and spans the period from earliest deployment return date (28 February 2002) to most recent mental disorder diagnosis date (24 January 2011).

Potential confounders

Researchers have identified a number of correlates with mental healthcare seeking in those with mental health problems. Married individuals,19–21 females,3 10 21 22 younger age groups,3 10 those who have additional comorbidities,23 those with a history of mental healthcare19 and those with more severe illness21 24 25 have been identified as more likely to seek mental healthcare when needed. Among military personnel specifically, individuals in non-officer ranks21 26 as well as those with a lengthier military service3 have been identified as more likely to seek mental healthcare when needed. Some studies have also indicated that the strength of the association of these characteristics on delay to care can vary with specific mental disorders.3 20 27 Additionally, some authors suggest a number of facilitators to mental healthcare seeking, features that may directly have a positive influence on barriers to care seeking, such as the presence of a supportive organisational climate, social support facilitators and systems that educate on mental health and promote treatment seeking.6 These facilitators would potentially manifest differently among individuals differing in service (Army, Navy or Air Force), component (Regular or Reserve Force) and military occupation, which individually may characterise unique organisational environments. Additionally, individuals with live-in dependents may have unique social support needs relative to those without such dependents.

Based on this previous research, the potential confounders that we identified for this study included: mental disorder diagnosis-related variables; sex; age (≤29, 30–39 or ≥40); service (Army, Navy or Air Force); component (Regular or Reserve Force); rank category; military occupation; years of service (≤4, 5–9, 10–19 or ≥20 years); marital status; and presence of live-in dependents. Military occupation was categorised into eight groups:28 facility support (FS; eg, construction technicians, plumbing and heating technicians); health services (HS; eg, medical technicians, dental officers); information management (IM; eg, signal operators, communication and information systems technicians); intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR; eg, intelligence operators, communicator research positions); operations support (OPS support; eg, supply technicians, cooks); operations technicians (OPS tech; eg, electrical technicians, construction engineers); specialist (eg, legal positions, public affairs officers); and operations (OPS; eg, combat arms occupations).

The mental disorder diagnosis-related covariates included a past mental disorder diagnosis that was indicated in the mental health professionals' assessment and each Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition , that is DSM-IV-TR, (DSM) axis,29 excluding axis IV (ie, psychosocial and environmental problems). Military personnel in the CAF have an occupational fitness requirement, one that takes into consideration the potential duties required under the demanding and unpredictable conditions of operational deployments. Hence, any past diagnoses would have resolved prior to individual's Afghanistan deployment or these would have been judged to have no limitation on their readiness to deploy. DSM axis I diagnoses were categorised into seven groups: four single diagnosis categories of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depressive disorder (ie, major depression or dysthymic disorder), adjustment disorder or single ‘other’ disorder and three comorbid categories of PTSD and depressive disorder only, all other comorbid combinations with PTSD and any other non-PTSD comorbid combination. The ‘other’ disorders included non-PTSD anxiety disorders, mood disorders other than major depression and dysthymic disorder, somatoform disorder, and substance-related disorders. Axis II information was dichotomised based on the presence of a personality disorder or trait, while axis III information was categorised based on the identification of a relevant musculoskeletal condition, another condition, or none. Relevant axis III conditions comorbid with a musculoskeletal condition were assigned to the musculoskeletal category. Functional status (reflected by axis V, the Global Assessment of Functioning) was categorised into four groups:29 0–50 (severe symptoms); 51–60 (moderate symptoms); 61–70 (mild symptoms); and 71–100 (transient symptoms).

Statistical analysis

The data were analysed using SAS for Windows, V.9.3 (SAS Institute, North Carolina, USA), and incorporated sample weights. Taylor series linearisation methods30 were used to determine 95% CIs. Missing values were identified for marital status (n=6), the presence of live-in dependents (n=22) and DSM axis V (n=71). The fully conditional specification multiple imputation method31 was implemented when analysing these covariates.

We used time-to-event analysis methods. Zero-time was defined as the most recent Afghanistan-related deployment return date prior to diagnosis; the median was 17 February 2007, ranging from 28 February 2002 to 31 May 2009. Event time was the diagnosis date of individuals' Afghanistan service-related mental disorder; the median was 01 September 2008, ranging from 21 September 2002 to 24 January 2011. No individuals were censored.

Age, years of service and era covariates were handled as time-dependent covariates. Marital status, the presence of live-in dependents and diagnosis-related covariates (ie, previous mental disorder diagnoses and DSM axis information) were captured at individuals' diagnosis date. All other covariates (ie, sex, element, component and rank category) were captured at the start of follow-up.

Weighted, extended Kaplan-Meier methods32 generated event probabilities for era as a time-dependent covariate. Weighted Cox regression assessed relative delay to care differences for covariates and results were expressed as HRs and their 95% CIs. The primary covariate of interest (era) was forced into a regression model that included potential confounders selected using a two-stage approach. Initially, weighted Cox regressions assessed the unadjusted relationship between each potential confounder and delay to care; covariates with a Wald test p<0.25 were initially retained. In the second stage, backwards elimination removed potential confounders using a Wald test p value threshold of 0.10. Regression diagnostic plots were reviewed with respect to the proportional hazards assumption.33

Results

Study cohort characteristics

Table 1 summarises the study participants' sociodemographic and military characteristics. Individuals in the cohort with an Afghanistan deployment-related mental disorder largely consisted of men, Regular Force members and Army service personnel. At the start of follow-up, the majority of individuals were younger than 40, in junior non-commissioned member ranks and just over half had <10 years of service while 23.1% had <5 years of service. Although half of the participants were in the ‘Operations’ occupation category, 90.0% of these were combat arms occupations. At their diagnosis date a majority of individuals were married and had no live-in dependents.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and military characteristics of the study subset (weighted N=4108; sample n=415) and their unadjusted association (HR) with delay to care following deployment return

| Characteristic | Unweighted sample no. | Weighted % | Mean delay to care (days) |

Unadjusted HR |

95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95% CI | |||||

| Occupation categorisation* | ||||||

| FS | 9 | 2.7 | 316 | 123 to 509 | 1.88 | 0.91 to 3.88 |

| HS | 27 | 6.1 | 457 | 294 to 621 | 1.21 | 0.77 to 1.91 |

| IM | 23 | 4.8 | 478 | 320 to 636 | 1.17 | 0.76 to 1.79 |

| ISR | 17 | 3.6 | 397 | 216 to 578 | 1.44 | 0.83 to 2.50 |

| OPS support | 73 | 13.8 | 649 | 503 to 795 | 0.82 | 0.59 to 1.12 |

| OPS tech | 40 | 11.8 | 606 | 434 to 778 | 0.89 | 0.62 to 1.29 |

| Specialist | 28 | 7.4 | 585 | 439 to 731 | 0.95 | 0.68 to 1.35 |

| OPS | 198 | 49.8 | 549 | 475 to 623 | Reference | |

| Occupation categorisation (aggregated)* | ||||||

| FS† | 9 | 2.7 | 316 | 123 to 509 | 1.85 | 0.92 to 3.76 |

| OPS support‡ | 73 | 13.8 | 649 | 503 to 795 | 0.81 | 0.60 to 1.08 |

| Other | 333 | 83.5 | 543 | 489 to 597 | Reference | |

| Component | ||||||

| Reserve Forces | 20 | 8.1 | 536 | 328 to 743 | 1.07 | 0.68 to 1.67 |

| Regular Forces | 395 | 91.9 | 553 | 500 to 606 | Reference | |

| Service | ||||||

| Air Force | 47 | 10.7 | 596 | 414 to 778 | 0.85 | 0.59 to 1.24 |

| Navy | 36 | 12.9 | 651 | 476 to 825 | 0.79 | 0.57 to 1.10 |

| Army | 332 | 76.4 | 528 | 475 to 582 | Reference | |

| Rank* | ||||||

| Officer | 39 | 11.0 | 694 | 499 to 890 | 0.72 | 0.50 to 1.05 |

| SNCM | 107 | 24.3 | 576 | 487 to 666 | 0.89 | 0.71 to 1.12 |

| JNCM | 269 | 64.7 | 518 | 454 to 581 | Reference | |

| Sex* | ||||||

| Female | 52 | 10.8 | 422 | 295 to 549 | 1.39 | 0.96 to 2.02 |

| Male | 363 | 89.2 | 567 | 512 to 622 | Reference | |

| Age (time dependent)¶ | ||||||

| ≤29 | 166 | 40.3 | 540 | 457 to 622 | Reference | |

| 30–39 | 175 | 39.6 | 546 | 467 to 624 | 1.17 | 0.88 to 1.55 |

| ≥40 | 74 | 20.1 | 587 | 466 to 708 | 1.10 | 0.80 to 1.49 |

| Years of service (time dependent)*,¶ | ||||||

| ≤4 | 90 | 23.1 | 698 | 571 to 825 | Reference | |

| 5–9 | 117 | 28.8 | 489 | 404 to 574 | 1.59 | 1.11 to 2.27 |

| 10–19 | 153 | 33.4 | 538 | 452 to 624 | 1.44 | 1.00 to 2.06 |

| ≥20 | 55 | 14.7 | 474 | 371 to 578 | 1.77 | 1.20 to 2.60 |

| Marital status (MI)** | ||||||

| Married | 293 | 71.4 | 559 | 498 to 621 | Reference | |

| Single—never married | 81 | 19.1 | 500 | 377 to 623 | 1.11 | 0.81 to 1.53 |

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 35 | 8.2 | 633 | 485 to 781 | 0.86 | 0.64 to 1.16 |

| Unspecified | 6 | 1.3 | 353 | 97 to 610 | ||

| Live-in dependents (MI)*,** | ||||||

| Yes | 193 | 44.1 | 612 | 527 to 697 | 0.83 | 0.66 to 1.04 |

| No | 200 | 50.2 | 517 | 447 to 587 | Reference | |

| Unspecified | 22 | 5.7 | 386 | 272 to 500 | ||

*The Wald test p<0.25 for variables: occupation categorisation, sex, rank, years of service and live-in dependents (MI).

†Facility support included occupations such as construction engineers, fire fighters, plumber/gas fitter and technicians in—water, fuels and the environment, electrical distribution, plumbing and heating, refrigeration and mechanical systems, and weather systems processing.

‡Operations support included occupations such as logistics support, air traffic controllers, supply technicians, traffic technicians, postal clerks, administrative clerks, financial clerks, resource management support clerks and mobile support equipment operators.

¶Age and years of service were time-dependent variables, sample number, weighted %, and mean delay to care with the associated 95% CI are reported here at the deployment return date. The reported unadjusted HR and 95% CI incorporate the variables' time dependency.

**Multiple imputation was used to compute the unadjusted HR for variables: marital status (MI) and live-in dependents (MI).

FS, facility support; HS, health services; IM, information management; ISR, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance; JNCM, junior non-commissioned member; MI, multiple imputation used; OPS support, operations support; OPS tech, operations technicians; OPS, operations; SNCM, senior non-commissioned member.

Table 2 summarises the various clinical characteristics. PTSD was the most diagnosed condition (59.3%), followed by depressive disorder (ie, major depression or dysthymic disorder) (46.7%). PTSD was diagnosed alone in 17.7% of individuals but comorbid with depressive disorder alone in 17.7% and with other mental disorder(s) in 23.9%. A majority of individuals had no identified mental disorder diagnosis history or personality disorder (DSM axis II) and 48.7% had an identified relevant physical medical condition (DSM axis III).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics among individuals of the study subset (weighted N=4108; sample n=415) and their unadjusted association (HR) with delay to care following deployment return

| Clinical characteristic | Unweighted sample no. | Weighted % | Mean delay to care (days) |

Unadjusted HR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95% CI | |||||

| Era (at most recent deployment return date) | ||||||

| 2002/2004 | 92 | 24.5 | 799 | 647 to 951 | Reference | Reference |

| 2005/2006 | 96 | 20.7 | 555 | 444 to 666 | 1.62 | 1.13 to 2.33 |

| 2007 | 100 | 23.8 | 515 | 439 to 590 | 1.98 | 1.40 to 2.80 |

| 2008 | 87 | 20.4 | 428 | 353 to 503 | 2.48 | 1.72 to 3.57 |

| 2009/2010 | 40 | 10.6 | 295 | 230 to 361 | 3.97 | 2.62 to 6.01 |

| Era (time dependent)* | ||||||

| 2002/2004 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 2005/2006 | 1.34 | 0.79 to 2.27 | ||||

| 2007 | 1.49 | 0.88 to 2.51 | ||||

| 2008 | 1.13 | 0.68 to 1.88 | ||||

| 2009/2010 | 2.79 | 1.74 to 4.47 | ||||

| Mental disorder diagnosis history | ||||||

| Yes | 96 | 22.0 | 534 | 412 to 656 | 1.04 | 0.78 to 1.39 |

| None indicated | 319 | 78.0 | 556 | 501 to 612 | Reference | Reference |

| Mental disorder diagnosis case mix | ||||||

| PTSD only | 74 | 17.7 | 539 | 432 to 646 | 0.86 | 0.56 to 1.32 |

| Depressive disorder only | 39 | 13.3 | 633 | 437 to 829 | 0.71 | 0.43 to 1.20 |

| Other single diagnosis only | 26 | 7.0 | 474 | 286 to 662 | 1.00 | 0.55 to 1.80 |

| Adjustment disorder only | 44 | 9.0 | 467 | 321 to 612 | Reference | Reference |

| PTSD and depressive disorder | 76 | 17.7 | 524 | 415 to 634 | 0.90 | 0.58 to 1.39 |

| PTSD and other | 109 | 23.9 | 601 | 504 to 697 | 0.76 | 0.50 to 1.15 |

| Any other combination (excl. PTSD) | 47 | 11.4 | 529 | 360 to 698 | 0.88 | 0.53 to 1.48 |

| DSM IV—axis II personality disorder/trait† | ||||||

| Yes | 53 | 13.0 | 630 | 487 to 772 | 0.84 | 0.63 to 1.13 |

| None indicated | 362 | 87.0 | 540 | 486 to 594 | Reference | Reference |

| DSM IV—axis III General Medical Conditions Present† | ||||||

| Musculoskeletal | 111 | 27.6 | 562 | 446 to 678 | 0.88 | 0.65 to 1.18 |

| Other | 92 | 21.1 | 650 | 536 to 765 | 0.75 | 0.58 to 0.97 |

| None indicated | 212 | 51.3 | 505 | 440 to 570 | Reference | Reference |

| DSM IV—axis V Global Assessment of Functioning (MI)‡ | ||||||

| 0–50: severe symptoms | 43 | 9.2 | 561 | 421 to 701 | 0.99 | 0.62 to 1.57 |

| 51–60: moderate symptoms | 133 | 30.6 | 497 | 409 to 585 | 1.12 | 0.76 to 1.65 |

| 61–70: mild symptoms | 127 | 32.0 | 612 | 517 to 708 | 0.93 | 0.60 to 1.43 |

| 71–100: transient symptoms | 41 | 10.1 | 541 | 386 to 695 | Reference | Reference |

| Unspecified | 71 | 18.1 | 536 | 403 to 669 | ||

*Here, era is used as a time-dependent variable; individuals' era membership changes with time and as such, the sample number, weighted % and mean delay to care with its associated 95% CI are not reported. The provided unadjusted HR and 95% CI incorporate the time dependency of the era variable.

†The Wald test p<0.25 for variables: DSM IV—axis II personality disorder/trait and DSM IV—axis III General Medical Conditions Present. ‡Multiple imputation was used to compute the unadjusted HR for the DSM IV—axis V Global Assessment of Functioning (MI) variable.

DSM IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; MI, multiple imputation used, PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Delay to care

The mean delay to care was 551 days (95% CI 501 to 602 days; median: 400 days; IQR: 191–747 days). The mean delay varied with occupational category; the FS category had the shortest mean delay and the OPS support category had the longest delay. In subsequent analyses, occupation was assessed as a three category variable (FS, OPS support and other). The unadjusted HRs suggest that delay to care was slightly longer for officers, males, individuals with <5 years of military service, individuals with live-in dependents (table 1) and individuals with non-musculoskeletal medical conditions (table 2). However, having a previous mental disorder, specific mental disorder diagnoses and disorder severity were not associated with significantly longer delays to care (table 2).

Mental health system era

The mean delay to care gradually decreased with more recent eras when characterised, and time-fixed, at deployment return date (table 2). It varied from a high of 799 days (95% CI 647 to 951) in the 2002/2004 era to a low of 295 days (95% CI 230 to 361) in the 2009/2010 era. These comparisons with era as a time-fixed variable are not ideal metrics, as all individuals in this analysis ultimately sought care and late care seekers have more opportunity to be identified during the longer follow-up for earlier eras. Hence, era was more fully analysed as a time-dependent variable, an approach that defines individuals' initial era at their deployment return date but incorporates the potential for this era designation to change as time passes without mental healthcare being sought.

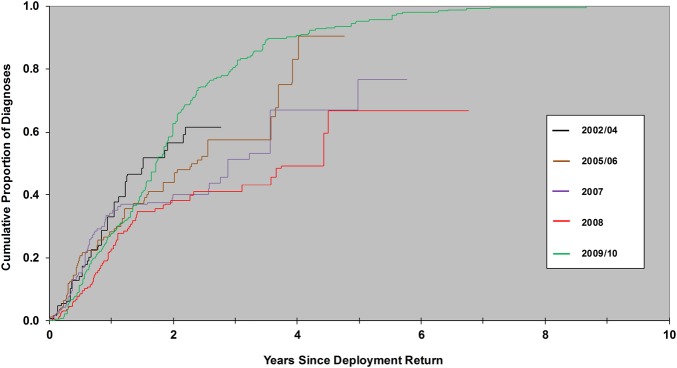

Extended Kaplan-Meier curves were generated for era that incorporates its time-dependent nature (figure 1).32 These curves begin to show some separation after about 2 years of follow-up, suggesting that differences in delay to care with era were only realised among individuals who had not yet received care by 2 years after return from deployment.

Figure 1.

Extended Kaplan-Meier cumulative probabilities for delay to mental healthcare among Canadian Armed Forces personnel who deployed in support of the mission in Afghanistan and were subsequently diagnosed with an Afghanistan service-related mental disorder by mental health system era (2002/2004, 2005/2006, 2007, 2008, 2009/2010), assessed as a time-dependent covariate.

Cox proportional hazards regression results

Cox regressions generated unadjusted HRs for era, analysed as a time-dependent variable, which indicate that while all eras had a shorter delay to care relative to the initial 2002/2004 era, the relative delay was only statistically significant for the 2009/2010 era (unadjusted HR, 2.79 (95% CI 1.74 to 4.47)). Similarly, era to subsequent era comparisons indicate that only the 2009/10 era had a statistically significant shorter delay to care relative to the previous 2008 era (unadjusted HR, 2.47 (95%CI 1.78 to 3.43)).

The final multivariable model that assessed mental health system era retained sex, military occupation, rank category, years of service and DSM axis III variables as potential confounders. This adjusted model (table 3) showed that the delay to care was significantly shorter for individuals in era 2009/2010 relative to era 2002/2004 (adjusted HR (aHR), 3.01 (95% CI 1.91 to 4.73)); the aHRs associated with eras 2005/2006, 2007 and 2008 were elevated, indicating shorter delays to care relative to the 2002/2004 era, but these were not statistically significant. Era to subsequent era comparisons indicated that only the most recent era (2009/2010) had a significantly shorter time to care relative to the previous 2008 era (aHR, 2.54 (95% CI 1.83 to 3.51)). These findings mirror what was found in the unadjusted Cox regression analysis for era.

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazard regression assessment of the adjusted association of mental health system era (era) with delay to care among Canadian Armed Forces personnel who deployed in support of the mission in Afghanistan (2001–2008) and were subsequently diagnosed with an Afghanistan service-related mental disorder

| Characteristic* | Adjusted HR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Era (time dependent) | ||

| 2002/2004 | Reference | Reference |

| 2005/2006 | 1.43 | 0.87 to 2.37 |

| 2007 | 1.57 | 0.95 to 2.61 |

| 2008 | 1.19 | 0.72 to 1.95 |

| 2009/2010 | 3.01 | 1.91 to 4.73 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1.57 | 1.13 to 2.18 |

| Male | Reference | Reference |

| Rank | ||

| Officer | 0.62 | 0.43 to 0.90 |

| SNCM | 0.68 | 0.53 to 0.89 |

| JNCM | Reference | Reference |

| Years of service (time dependent) | ||

| ≤4 | Reference | Reference |

| 5–9 | 1.88 | 1.36 to 2.61 |

| 10–19 | 1.96 | 1.35 to 2.85 |

| ≥20 | 2.77 | 1.86 to 4.14 |

| Occupation categorisation | ||

| FS† | 1.47 | 0.61 to 3.52 |

| OPS support‡ | 0.72 | 0.55 to 0.95 |

| Other | Reference | Reference |

| DSM IV—axis III General Medical Conditions Present | ||

| Musculoskeletal | 0.91 | 0.69 to 1.21 |

| Other | 0.71 | 0.54 to 0.92 |

| None indicated | Reference | Reference |

*A backwards elimination selection process identified the live-in dependents and DSM IV—axis II personality disorder/trait variables for removal from the final assessment model.

†Facility support included occupations such as construction engineers, fire fighters, plumber/gas fitter, and technicians in: water, fuels and the environment, electrical distribution, plumbing and heating, refrigeration and mechanical systems, and weather systems processing.

‡Operations support included occupations such as logistics support, air traffic controllers, supply technicians, traffic technicians, postal clerks, administrative clerks, financial clerks, resource management support clerks and mobile support equipment operators.

DSM IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; FS, facility support; JNCM, junior non-commissioned member; MI, multiple imputation used; OPS support, operations support; SNCM, senior non-commissioned member.

Delay to care varied by sex, occupation category, rank, DSM axis III and years of service. Men, operations support occupations, higher ranks, non-musculoskeletal comorbidities and fewer years of military service were associated with longer delays to mental healthcare (table 3).

Discussion

Key results

We observed a mean delay to care of 551 days (median: 400 days) among individuals who deployed in support of the mission in Afghanistan and were subsequently diagnosed with an Afghanistan service-related mental disorder. The delay tended to decrease over time from the initially observed era (2002/2004) to more recent ones; however, only the most recent era (2009/2010) was associated with a statistically significant shorter delay to care. The time to care for the 2009/2010 era was 3.0 times shorter relative to the 2002/2004 era and 2.5 times shorter relative to the 2008 era. It was further noted that these changes in delay to care were predominantly manifested among individuals with a delay of almost 2 years or longer, and who were more likely to receive care in the most recent era.

We identified some additional independent associations with delay to mental healthcare. Similar to what has been reported by others, males,3 10 higher ranks,26 the presence of certain physical comorbidities23 and fewer years of military service3 were associated with longer delays to care. Additionally, certain occupation categories were associated with longer delays and this may possibly be associated with work environment influences that have been reported by others.6

Disorder severity, as measured by the DSM axis V functional impairment rating at diagnosis, and a previous mental disorder diagnosis, a proxy for prior mental health system encounters, were not significantly associated with differences in delay to care. Intuitively, one would have expected early care seeking among those with more severe disorder symptoms and those with prior mental health treatment-seeking behaviour, as has been noted by others.6 10 Similarly, while we observed some variation in the delay to care by mental disorder groupings, these were not statistically significant and contrast with differences in delay to care by disorder that have been reported by others.3 8 34

Comparison with other findings

Very few studies have quantified delay to mental healthcare among military personnel. In one study, researchers used a questionnaire among Canadian military personnel in 2002 to identify the year of onset for specific mental disorders and the subsequent age of first contact with a mental health professional to estimate median delays of 7, 3, 3 and 8 years for PTSD, major depressive disorder, generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder, respectively.3 Although the researchers found that the majority of study participants with a disorder eventually sought help, 89–100%, the delays were substantially higher than the median delay of 1.1 years identified in the current study. However, while we noted that delays decreased with more recent eras, methodological differences likely account for the much longer delays to care identified by Fikretoglu et al.3 We focused on individuals with an Afghanistan service-related mental disorder diagnosis and used a somewhat more precise estimate of the precipitating event (deployment) that was obtained from administrative records, as opposed to questionnaires that rely on respondents' recall.

Temporal changes in the barriers that drive excessive delays to care have been noted. Studies among US military personnel suggest that perceptions of stigma and barriers to care have reduced some over the past decade.18 35 One study among US National Guard soldiers reported a reduction in the percentage of individuals endorsing negative beliefs and stigma related to treatment over 2007 to 2012; however, the percentage endorsing barriers associated with career concerns did not change.35 Similarly, a study among active duty US military personnel reported that those who indicated seeking mental healthcare would damage their career reduced from 48% to 35% over 2002 to 2008.18

Delay to mental healthcare seeking among civilian populations has also been investigated. Data from the WHO's World Mental Health surveys indicated that among participating countries median delays to treatment ranged from 3 to 30 years for anxiety disorders, 1 to 14 years for mood disorders and 6 to 18 years for substance use disorders.8 Similarly, survey data collected from civilians over 2004 to 2005 in the USA indicated median delays to treatment contact of <1 year for panic disorder and 1 year for generalised anxiety disorder.34 This contrasts with survey data collected over 2001 to 2003, where median delays to treatment contact were 10 years for panic disorder and 9 years for generalised anxiety disorder.7

Strengths and limitations

This study has a number of strengths. It is one of the few studies to quantify delay to care for service-related mental disorders in a military population. Additionally, it is unique in its use of an objective measure of delay to care from an apparent need for care, as indicated by a disorder that resulted from an attributed deployment exposure, to a concrete measure of care being received for the apparent need, as defined by the specific service-related diagnosis. Other research in this area that we were able to identify had used questionnaires or administrative records to measure delay to care and thus, lacked the precision that we were able to measure. Second, this paper is unique in its demonstration that delay to care for mental health problems can be favourably adjusted through initiatives to reduce barriers to care-seeking and system augmentations to increase the capacity to provide mental healthcare. Other research demonstrating this could not be identified. While it's possible that there were some unmeasured influences on delay to care that resulted in the observed delay to care changes, our methods controlled for a large number of known potential confounders and thus, support our assertion.

This study's primary limitation relates to its observational nature: we sought to explore changes in delay to care as a function of era, a proxy for evolutionary changes in the CAF mental health system but also a proxy for other unmeasured environmental changes. While we identified approximate dates for various enhancements to the mental health system, each did not occur in isolation and some enhancements were introduced and then further augmented over time to increase their reach and perceived effectiveness. Second, we investigated delay to care among only those who ultimately sought care for an Afghanistan service-related mental disorder, given the clearer temporal association between precipitating event, symptom-onset and diagnosis, excluding individuals who sought care for a subclinical mental health problem or had a disorder that was unrelated to an Afghanistan deployment. Additionally, it is possible that the era-associated mental health system changes impacted delay to care differently for Afghanistan service-related mental disorders relative to other disorders.

Implications

Delays to mental healthcare among military and civilian populations were substantial in the past,3 8 impacting individuals' quality of life and functioning.36 As a response, the CAF gradually renewed its mental healthcare system, increasing capacity and implementing programmes that focus on reducing barriers to care. Our findings provide some evidence that those efforts have been associated with shorter delays to care, particular in 2009/2010. Unfortunately, the multifaceted and evolutionary nature of health system transformation in the CAF means that we can't say precisely which elements were most beneficial. However, the largest change in delay to care that we identified was associated with the time period during which the CAFs resilience and mental health training programme was implemented (and later, further augmented) and when a shortage of mental health professionals was being addressed.

It is likely that the CAFs individual mental health system reinforcements interacted to provide an environment in which some who were hesitant to seek care became less, so and/or created an environment with reduced wait times for those seeking care; however, our study cannot comment on those who may have had a need for mental healthcare but did not seek it over this study's follow-up period. While our results are encouraging, suggesting that CAF mental health system augmentations have been beneficial, further refinement and the application of its most beneficial components to other settings will require more focused evaluation of individual programmes and services. Hence, there is a need for evaluation studies of CAF programmes, particularly its postdeployment mental health screening, as well as its resilience and mental health training programmes. Additionally, there is a need to verify that structural barriers to mental healthcare are low and remain so with time (eg, ensuring personnel have knowledge of available care, ease of access, appropriate waiting times, optimised treatment effectiveness and sufficient time to seek care).

Conclusion

The CAF and other military organisations have invested heavily in their mental health systems. We found that the CAF investments were associated with an encouraging decrease in delay to care. While these findings speak to the potential impact of mental health services renewal and efforts to shorten delay to care, evaluation studies of the component changes in the CAF mental health system are warranted.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Julie Lanouette and Suzanne Giroux for their assistance with the data collection from patient medical records.

Footnotes

Contributors: DB had full access to all data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. DB and MAZ contributed to the study design and the interpretation of the study results. DB wrote the initial draft of the manuscript, and DB and MAZ contributed to subsequent revisions. DB and MAZ have read and agree with the manuscript's final content.

Funding: This work was supported by funding from the Canadian Armed Forces Surgeon General's Medical Research Program.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This research was approved by Veritas Research Ethics Board (Dorval, QC).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Seal KH, Metzler TJ, Gima KS et al. Trends and risk factors for mental health diagnoses among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans using Department of Veterans Affairs health care, 2002–2008. Am J Public Health 2009;99:1651–8. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.150284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boulos D, Zamorski MA. Deployment-related mental disorders among Canadian Forces personnel deployed in support of the mission in Afghanistan, 2001–2008. CMAJ 2013;185:E545–52. 10.1503/cmaj.122120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fikretoglu D, Liu A, Pedlar D et al. Patterns and predictors of treatment delay for mental disorders in a nationally representative, active Canadian military sample. Med Care 2010;48:10–17. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181bd4bf9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC et al. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. N Engl J Med 2004;351:13–22. 10.1056/NEJMoa040603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vogt D. Mental health-related beliefs as a barrier to service use for military personnel and veterans: a review. Psychiatr Serv 2011;62:135–42. 10.1176/ps.62.2.pss6202_0135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zinzow HM, Britt TW, McFadden AC et al. Connecting active duty and returning veterans to mental health treatment: interventions and treatment adaptations that May reduce barriers to care. Clin Psychol Rev 2012;32:741–53. 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M et al. Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in The National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:603–13. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang PS, Angermeyer M, Borges G et al. Delay and failure in treatment seeking after first onset of mental disorders in the World Health Organization's World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry 2007;6:177–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Sampson NA et al. Barriers to mental health treatment: results from The National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol Med 2011;41:1751–61. 10.1017/S0033291710002291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrade LH, Alonso J, Mneimneh Z et al. Barriers to mental health treatment: results from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Psychol Med 2014;44:1303–17. 10.1017/S0033291713001943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thornicroft G. Stigma and discrimination limit access to mental health care. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc 2008;17:14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Commonwealth of Australian. Capability through mental fitness: 2011 Australian Defence Force Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy. http://www.defence.gov.au/health/dmh/docs/2011adfmentalhealthandwellbeingstrategy.pdf (accessed 29 Sep 2014).

- 13.Department of Defence Task Force on Mental Health. An achievable vision: report of the Department of Defense Task Force on Mental Health. Falls Church, Virginia: Defense Health Board, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Department of National Defence and The Canadian Armed Forces. Surgeon General's Mental Health Strategy: Canadian Forces Health Services Group—An Evolution of Excellence. http://cmp-cpm.forces.mil.ca/health-sante/pub/pdf/sgmhs-smgmsm-eng.pdf (accessed 3 Oct 2014).

- 15.Gould M, Adler A, Zamorski M et al. Do stigma and other perceived barriers to mental health care differ across Armed Forces? J R Soc Med 2010;103:148–56. 10.1258/jrsm.2010.090426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bailey S. The Canadian Forces Health Services Road to Mental Readiness Programme. Medical Corp International Forum 2015[2], 37–39. Bonn, Germany: Beta Publishing Group, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Osorio C, Jones N, Fertout M et al. Changes in stigma and barriers to care over time in U.K. Armed Forces deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq between 2008 and 2011. Mil Med 2013;178:846–53. 10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quartana PJ, Wilk JE, Thomas JL et al. Trends in mental health services utilization and stigma in US soldiers from 2002 to 2011. Am J Public Health 2014;104:1671–9. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blais RK, Renshaw KD. Stigma and demographic correlates of help-seeking intentions in returning service members. J Trauma Stress 2013;26:77–85. 10.1002/jts.21772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fikretoglu D, Brunet A, Schmitz N et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and treatment seeking in a nationally representative Canadian military sample. J Trauma Stress 2006;19:847–58. 10.1002/jts.20164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hines LA, Goodwin L, Jones M et al. Factors affecting help seeking for mental health problems after deployment to Iraq and Afghanistan. Psychiatr Serv 2014;65:98–105. 10.1176/appi.ps.004972012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maguen S, Cohen B, Cohen G et al. Gender differences in health service utilization among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21:666–73. 10.1089/jwh.2011.3113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakash O, Levav I, Aguilar-Gaxiola S et al. Comorbidity of common mental disorders with cancer and their treatment gap: findings from the World Mental Health Surveys. Psychooncology 2014;23:40–51. 10.1002/pon.3372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J et al. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA 2004;291:2581–90. 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang PS, Berglund PA, Olfson M et al. Delays in initial treatment contact after first onset of a mental disorder. Health Serv Res 2004;39:393–415. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00234.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hernandez SH, Bedrick EJ, Parshall MB. Stigma and barriers to accessing mental health services perceived by Air Force nursing personnel. Mil Med 2014;179:1354–60. 10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blais RK, Renshaw KD, Jakupcak M. Posttraumatic stress and stigma in active-duty service members relate to lower likelihood of seeking support. J Trauma Stress 2014;27:116–19. 10.1002/jts.21888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bender P. Towards a sustainable CF: a risk analysis model. Department of National Defence, 2005:2005–10. [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th edn, text revision Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolter KM. Introduction to variance estimation. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Buuren S. Multiple imputation of continuous and discrete data by fully conditional specification. Stat Methods Med Res 2007;16:219–42. 10.1177/0962280206074463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Snapinn S, Jiang Q, Iglewicz B. Ilustrating the impact of a time-varying covariate with an extended Kaplan-Meier estimator. Am Statistician 2005;59:301–7. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klein JP, Moeschberger ML. Survival analysis: techniques for censored and truncated data. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iza M, Olfson M, Vermes D et al. Probability and predictors of first treatment contact for anxiety disorders in the United States: analysis of data from The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). J Clin Psychiatry 2013;74:1093–100. 10.4088/JCP.13m08361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valenstein M, Gorman L, Blow AJ et al. Reported barriers to mental health care in three samples of U.S. Army National Guard soldiers at three time points. J Trauma Stress 2014;27:406–14. 10.1002/jts.21942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boulos D, Zamorski MA. Do shorter delays to care and mental health system renewal translate into better occupational outcome after mental disorder diagnosis in a cohort of Canadian military personnel who returned from an Afghanistan deployment? BMJ Open 2015;5:e008591 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]