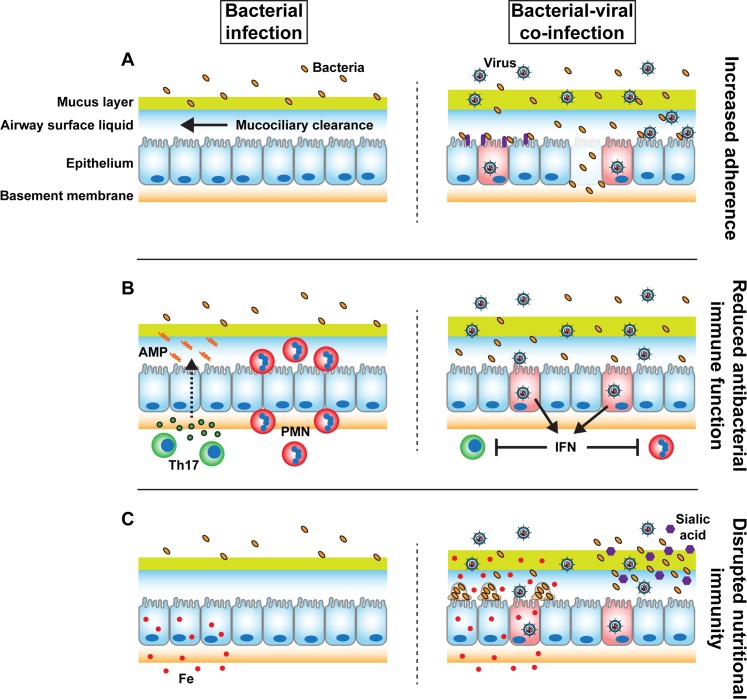

Fig 1. Model of increased susceptibility to secondary bacterial infection after primary viral infection of the respiratory epithelium.

(A) The respiratory epithelium restricts bacterial attachment via mucociliary clearance and maintenance of cell–cell junctions, which restricts access to bacterial receptors. During viral infection, ciliary beat is reduced, barrier function is disrupted, bacterial receptors (purple) are upregulated, and direct viral–bacterial interactions lead to increased bacterial adherence to the epithelium. (B) The respiratory epithelium recruits and activates neutrophils or polymorphonuclear (PMN, red) cells and T helper cells (particularly Th17, green) in response to detection of bacterial infection or pro-inflammatory cytokines. These effects lead to influx of neutrophils and stimulation of epithelial antimicrobial peptide/protein (AMP, orange spirals) production in response to IL-17 receptor signaling (green circles, dashed arrow) by the epithelium. During viral infection, epithelial cells produce interferons (IFN), which skew the immune status towards antiviral activity, suppressing neutrophil, Th17 responses, and other antibacterial functions. (C) To inhibit microbial growth, the respiratory epithelium actively restricts nutrient availability in the airway lumen, including limitation of luminal iron concentrations (Fe, red circles). During viral infection, interferon production leads to dysfunctional iron limitation, stimulating biofilm biogenesis. In the case of influenza infection, influenza stimulates mucin secretion and cleaves sialic acid (purple hexagons) from secreted mucins via neuraminidase activity. Common upper respiratory tract commensal bacteria can utilize liberated sialic acid as a nutrient.