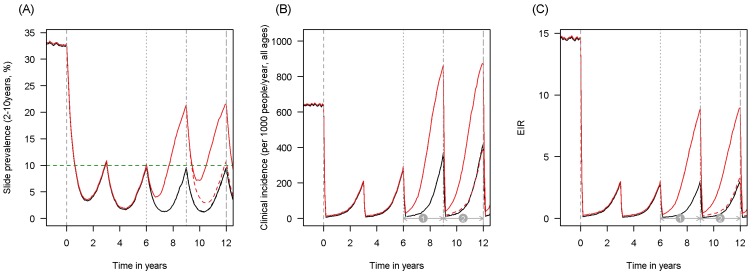

Figure 1. Scenario under investigation: timings for the introduction of LLINs, insecticide resistance and PBO LLINs for different malaria metrics.

The figure illustrates how insecticide resistance is incorporated into the mathematical model. Panel (A) shows parasite prevalence by microscopy in 2–10 year olds, (B) clinical incidence in the entire population (cases per 1000 people per year) and (C) the annual entomological inoculation rate (EIR). In all three panels 4 different scenarios are run: black line shows a situation with no insecticide resistance whilst red line illustrates resistance arriving at year 6 (moderate, 50% survival measured in a bioassay); solid lines show non-PBO LLIN whilst dashed lines show PBO LLINs introduced at year 9 (vertical dotted-dashed grey line). There is no vector control in the population up until time zero (vertical dashed grey line) at which time there is a single mass distribution of non-PBO LLINs to 80% of the population. LLINs are redistributed every 3 years to the same proportion of the population. Mosquitoes are entirely susceptible up until resistance arrives overnight at the start of year 6 (vertical grey dotted line). Endemicity (a variable in Figures 4 and 5) is changed by varying the slide prevalence in 2–10 year olds at year 6 (by changing the vector to host ratio) and in this plot takes a value of 10% (as illustrated by the horizontal green dashed line in A). The impact of insecticide resistance is predicted (in Figure 4) by averaging the clinical incidence and EIR for the solid red lines (resistance) and solid black lines (no resistance) between the years 6 and 9 (period  ). Similarly, the impact of switching to PBO LLINs (in Figure 5) is estimated by averaging the clinical incidence and EIR for the solid red line (standard LLINs) and dashed red lines (switch to PBO LLINs) lines between the years 9 and 12 (period

). Similarly, the impact of switching to PBO LLINs (in Figure 5) is estimated by averaging the clinical incidence and EIR for the solid red line (standard LLINs) and dashed red lines (switch to PBO LLINs) lines between the years 9 and 12 (period  ). Different scenarios with a low and high prevalence of pyrethroid resistance are shown in Figure 1—figure supplements 1 and 2.

). Different scenarios with a low and high prevalence of pyrethroid resistance are shown in Figure 1—figure supplements 1 and 2.

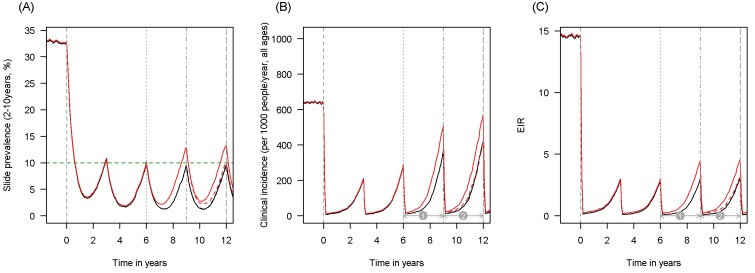

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. Scenario under investigation: example of a mosquito population with a low population prevalence of resistance.

). Similarly, the impact of switching to PBO LLINs (in Figure 5) is estimated by averaging the clinical incidence and EIR for the solid red line (standard LLINs) and dashed red lines (switch to PBO LLINs) lines between years 9 and 12 (period

). Similarly, the impact of switching to PBO LLINs (in Figure 5) is estimated by averaging the clinical incidence and EIR for the solid red line (standard LLINs) and dashed red lines (switch to PBO LLINs) lines between years 9 and 12 (period  ).

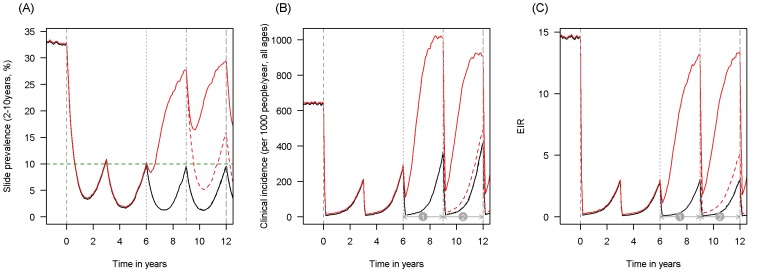

).Figure 1—figure supplement 2. Scenario under investigation: example of a mosquito population with a high population prevalence of resistance.

). Similarly, the impact of switching to PBO LLINs (in Figure 5) is estimated by averaging the clinical incidence and EIR for the solid red line (standard LLINs) and dashed red lines (switch to PBO LLINs) lines between years 9 and 12 (period

). Similarly, the impact of switching to PBO LLINs (in Figure 5) is estimated by averaging the clinical incidence and EIR for the solid red line (standard LLINs) and dashed red lines (switch to PBO LLINs) lines between years 9 and 12 (period  ).

).