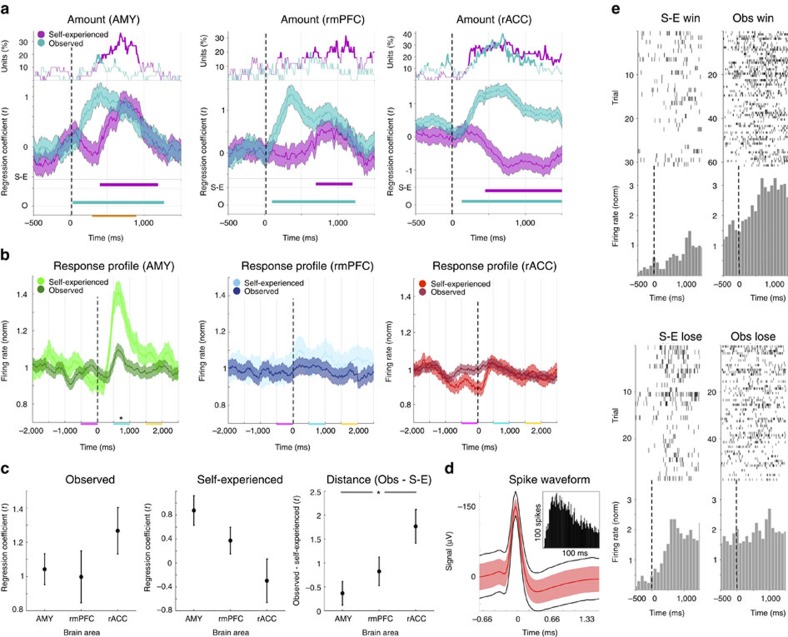

Figure 4. Amount encoding.

In this analysis only neurons showing a positive regression of their firing rate to the observed amount were included (n=30, 25 and 40 in the AMY (left), rmPFC (middle) and rACC (right), respectively). (a) Top panels: same as in Fig. 3. Middle panels: the mean (+/− s.e.m.) t-statistic of the regression coefficients of the firing rates to self-experienced amounts and observed amounts (revealed at t=0 ms). Bottom panels: time points after outcome with mean regression coefficient t-statistic values, for the sum of which a cluster statistical analysis across 10,000 label shuffled datasets was significant (α<0.01). We note that an increase in the regression coefficient for observed amounts after outcome is caused by the implicit selection bias; for self-experienced amounts, however, no selection bias was present. (b) The peristimulus time histograms of the selected populations of units were analyzed in the same way as in Fig. 2a revealing a significant difference in the AMY response amplitudes between self-experienced and observed trials (*P<0.05/3, n=1,800 and 3,600). (c) The mean values of the regression coefficients in a during the outcome period (300–900 ms, orange line in a). Post-hoc testing revealed a significant difference in the distance between observed and self-experienced values between the AMY and the rACC (*P<0.05/3, t-test, n=30 and 40 right panel). (d) Spike waveform of an example neuron presented as in Fig. 3d (n=10,536). (e) Raster plots and peristimulus time histograms for the same neuron as in d showing higher firing rates for self-experienced losses than for self-experienced wins and higher firing rates for observed wins than for observed losses reflecting the findings in a, left panel.