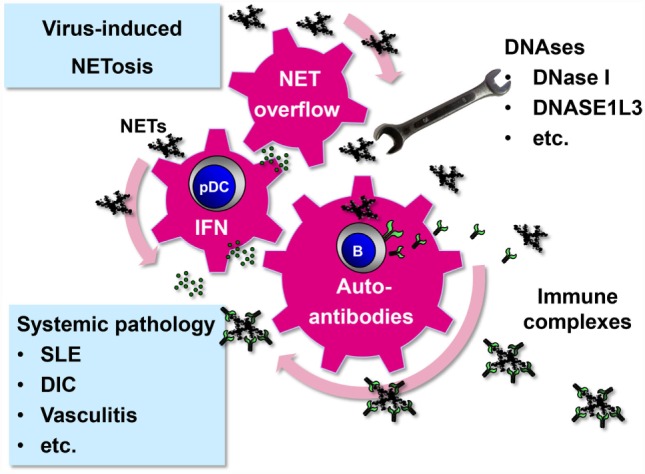

Figure 2.

Systemic pathology driven by virus-induced NET formation. Virus-induced NETs may start to circulate and become systemic under certain circumstances. First, systemic infection with viruses that have a strong NET-stimulatory capacity, such as hantaviruses, may overwhelm intact NET-degrading function of DNAses (20). Second, persistent viruses with low NET-inducing capacity, such as herpesviruses, may produce systemic NET excess if DNAse activity is compromised. As a result of NET overflow, self-reactive memory B cells are stimulated to release autoantibodies after binding and internalizing NET components through their B cell receptor (91). NETs are enriched in oxidized mitochondrial DNA inducing a strong inflammatory response (52). NETs stimulate pDCs to release type I IFN that adds momentum to the vicious cycle by further activating and expanding autoreactive B cells (48–50). Immune complexes are formed which not only cause systemic pathology as observed in several disease entities such as SLE but also promote the autoimmune process by driving a positive feedback loop.