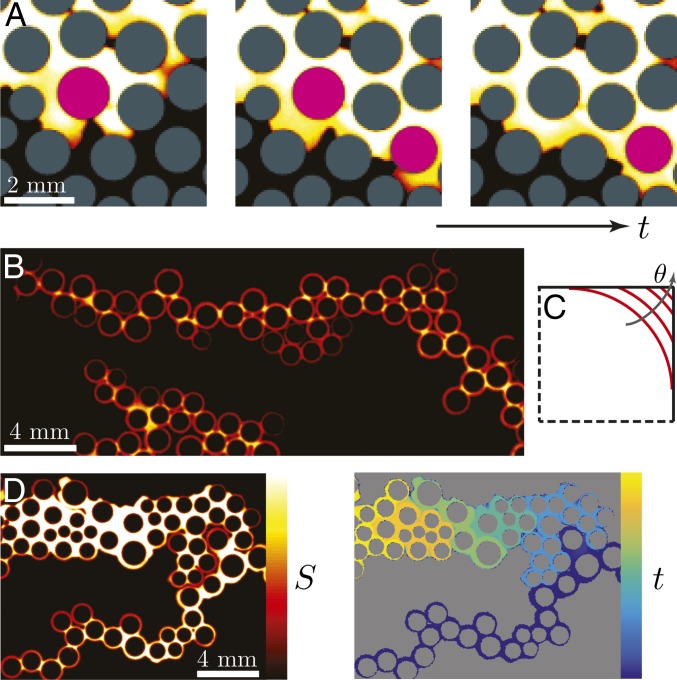

Fig. 4.

(A) Sequence of snapshots from weak imbibition at (Fig. 2L). Here, the invading water displaces the defending silicone oil in a cooperative manner: neighboring menisci overlap and form a new, stable meniscus. The posts where this occurs are highlighted in pink. This pore-scale mechanism is directly responsible for the increasing compactness of the macroscopic displacement pattern as θ decreases. (B) Snapshot from strong imbibition at (Fig. 2N) illustrating invasion by corner flow: the invading fluid advances by coating the perimeters of the posts rather than by filling the pore bodies. Pendular rings link the coated posts, forming chains. (C) For a given interfacial curvature, the interface is forced farther into the corner as θ increases, thereby reducing the cross-sectional area available for corner flow. The critical contact angle for corner flow in this geometry is . (D, Left) A snapshot from strong imbibition at (Fig. 2O) shows that the corner films coating the posts swell and expand over time. (Right) The same snapshot color coded by invasion time illustrates that strong imbibition at low Ca occurs in a burst-like manner, where groups of closely spaced posts are coated in rapid succession, followed by periods of inactivity.