Significance

A predictive understanding of landslide behavior remains elusive, to the extent that once landslide motion is detected the factors that control whether motion will remain slow or accelerate to catastrophic failure remain uncertain. Here, we adapt standard fault mechanics treatments to present a single model that captures both slow and catastrophic landslide motion. We test model predictions using field, laboratory, and remote sensing observations. The failure mode depends on the material properties and the dimensions of the landslide slip surface relative to a critical size. If the slip surface exceeds this size and has rate-weakening frictional properties then catastrophic failure must occur. However, landslides composed of rate-weakening material are characterized by slow sliding when the critical size exceeds landslide dimensions.

Keywords: landslides, slope failure, rate and state friction, pore-water pressure, effective stress

Abstract

Catastrophic landslides cause billions of dollars in damages and claim thousands of lives annually, whereas slow-moving landslides with negligible inertia dominate sediment transport on many weathered hillslopes. Surprisingly, both failure modes are displayed by nearby landslides (and individual landslides in different years) subjected to almost identical environmental conditions. Such observations have motivated the search for mechanisms that can cause slow-moving landslides to transition via runaway acceleration to catastrophic failure. A similarly diverse range of sliding behavior, including earthquakes and slow-slip events, occurs along tectonic faults. Our understanding of these phenomena has benefitted from mechanical treatments that rely upon key ingredients that are notably absent from previous landslide descriptions. Here, we describe landslide motion using a rate- and state-dependent frictional model that incorporates a nonlocal stress balance to account for the elastic response to gradients in slip. Our idealized, one-dimensional model reproduces both the displacement patterns observed in slow-moving landslides and the acceleration toward failure exhibited by catastrophic events. Catastrophic failure occurs only when the slip surface is characterized by rate-weakening friction and its lateral dimensions exceed a critical nucleation length that is shorter for higher effective stresses. However, landslides that are extensive enough to fall within this regime can nevertheless slide slowly for months or years before catastrophic failure. Our results suggest that the diversity of slip behavior observed during landslides can be described with a single model adapted from standard fault mechanics treatments.

Laboratory experiments (1, 2) and numerical models (3, 4) suggest that for slow-moving landslides that persist over periods of years to centuries (5) the shear strength that resists motion increases with slip rate—a characteristic referred to as rate strengthening—whereas the opposite is true for landslides that exhibit runaway acceleration and catastrophic failure. Two primary mechanisms are invoked frequently to describe the former rate-strengthening behavior. The first characterizes landslide materials as viscoplastic (i.e., Bingham-plastic), so that an increase in velocity corresponds with an increase in strain rate and viscous resistance. These models are able to reproduce field-based measurements of velocity for seasonally active slow-moving landslides (3). However, this constitutive behavior contradicts measurements that suggest landslide displacement is dominated by frictional sliding along basal and lateral faults (6); furthermore, such rheological models are unable to capture the transition from slow sliding to catastrophic failure. The second modeling approach applies Coulomb friction and invokes shear-zone dilatancy to regulate pore-water pressure changes so that sliding increases strength because of increases in effective stress associated with small porosity increases (1, 4, 7–9). Such models are able to describe both slow sliding and catastrophic failure because dilatant strengthening occurs only until a critical-state porosity is reached; subsequent consolidation can trigger catastrophic failure. Hence, although dilatant effects can be significant in particular cases (10), their ability to regulate the speeds of repeated slow-moving landslides is diminished if the shear-zone material cannot consolidate gradually between slip events.

Rate- and state-dependent changes in the friction coefficient itself provide an alternative framework for understanding changes in landslide velocity in response to the changes in pore-water pressure that are commonly associated with transient precipitation over a broad range of time scales. Similar descriptions that have been refined over the past 30 y yield successful predictions for a wide range of fault behavior, including stable sliding, slow slip and tremor, and the nucleation of earthquakes (11–13). These empirically based models subsume many complex processes that operate along fault zones, and, furthermore, can be parameterized to account for mechanical–hydrologic interactions such as dilatancy (7, 9). Because the slip surfaces of landslides and faults are both governed by frictional sliding and exhibit similar behavior (14), a fault mechanics approach might be suitably adapted to predict landslide motion.

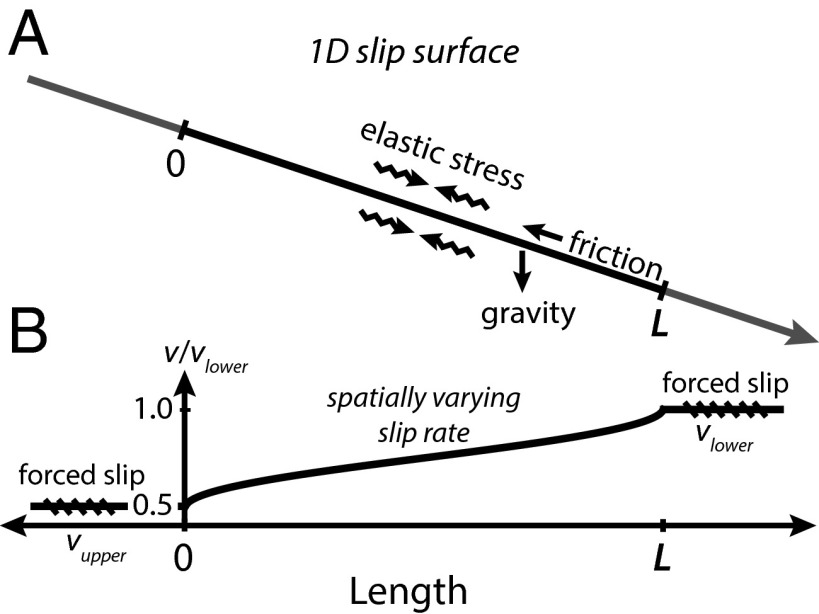

We formulated a rate and state friction model that can be driven by transient changes in effective normal stress (i.e., precipitation-induced changes in pore-water pressure) to describe both slow (characterized by transient or persistent sliding at low velocities) and accelerating dynamic motion, before the development of significant inertial effects. We perform model simulations at much lower effective stresses than are typically present along faults. This allows us to test rate and state friction model predictions in an unexplored stress regime. We consider an idealized one-dimensional Coulomb-plastic slip surface embedded in a homogeneous elastic medium (Fig. 1; see Materials and Methods for a brief discussion of slip near a free surface). Although it is generally accepted that the weathered rock and soil that overlies the landslide slip surface does not behave elastically over long timescales or for large displacements, elastic deformation can be significant for small displacement and strain over short timescales (i.e., transient motion) (15–17).

Fig. 1.

Schematic of model geometry and boundary conditions. (A) Model geometry for a simplified one-dimensional landslide, showing the dominant contributions to the force balance that are discussed in the text surrounding Eq. 3. The effects of changes in precipitation are modeled as leading to transient changes in effective stress along the sliding surface between 0 and L. (B) Boundary conditions and initial velocity profile along the landslide. The sliding surface is forced to slip at a small rate for and at for , where we set for all calculations. See Materials and Methods for more details.

The friction coefficient on the landslide sliding surface is described by refs. 18 and 19

| [1] |

where is the steady-state friction coefficient at reference velocity , a and b are friction parameters that control whether μ tends toward higher or lower values as slip rate v changes, and is the characteristic slip distance for the evolution of frictional contacts. The state variable θ, which is conceptualized as the average life span of a set of frictional contacts, evolves according to the Aging (or Dieterich) law where

| [2] |

so that at steady state. Stress balance requires that (20)

| [3] |

where is the driving stress due to gravity, is the effective normal stress (gravitational load minus pore-water pressure), G is the shear modulus, ν is the Poisson ratio, is the shear-wave speed, and the integral dependence on accounts for the elastic forcing associated with spatial gradients in slip along the sliding surface at local coordinate x. The first term on the right is the frictional stress and the second is the “radiation-damping” approximation for inertial effects, which become important only when the slip rate approaches (21). Additional model details are contained in Materials and Methods and SI Materials and Methods.

The elastic stress term in Eq. 3 accounts for the resistance to differential motion associated with longitudinal compression at grain contacts (i.e., the landslide is not modeled as an isolated block on a slope). Gradients in slip along the sliding surface are commonly observed in landslides (22). By considering the associated elastic interactions we are able to explore feedbacks between sliding velocity and both localized and spatially extensive stress perturbations. Although similar formulations have become standard in fault mechanics studies (12, 13, 20), the inclusion of elastic effects represents a key advance over previous rate and state friction models for landslides that ignore resistance to differential slip (23–26). As on tectonic faults, we suggest that whether incipient slip along a landslide surface accelerates or decelerates depends critically on a balance of forces involving both friction and elasticity.

Before presenting illustrative model results, we first review the stability conditions that ultimately determine whether a landslide governed by rate and state friction is capable of gaining significant inertia. Linear stability analysis demonstrates that landslides composed of rate-strengthening material, defined so that the frictional parameters satisfy , will never fail catastrophically (11, 18, 27). However, landslides composed of rate-weakening material () have the potential to display both catastrophic (dynamic) and noncatastrophic (slow) motion. For a homogeneous elastic material, the transition from slow to dynamic motion requires that the length L of the slipping surface exceeds a critical nucleation length that is given by (18)

| [4] |

A nominal range of parameter values compiled from measured properties in soil and rock mechanics experiments is given in Table S1. When , reductions in frictional strength with increased sliding velocity are compensated by elastic stresses associated with large strain gradients along the boundaries of the slipping region, whereas when the combined effects of friction and elastic stresses are ultimately unable to balance the driving stress, so unstable acceleration results. Here, we use our model to examine two types of landslides that are driven by precipitation-induced changes in pore-water pressure: (i) seasonally active slow-moving landslides and (ii) fast-moving catastrophic landslides. For the slow-moving landslides we ran simulations with rate-weakening, rate-strengthening, and rate-neutral frictional properties; all simulations for the fast-moving landslides were performed using rate-weakening properties.

Table S1.

Parameter values used in model simulations

| Symbol | Definition | Value (slow; catastrophic) | Refs. |

| Friction parameter | 0.008 | 45–47 | |

| Friction parameter | 0.012 | 45–47 | |

| Friction parameter | 0.01 | 45–47 | |

| b | Friction parameter | 0.01 | 45–47 |

| Characteristic slip distance, m | 4 × 10−2; 4 × 10−4 | 35, 62 | |

| Reference friction, m | 0.45; 0.6 | 45, 49 | |

| Shear wave velocity, m⋅s−1 | 250; 600 | 50, 51 | |

| ν | Poisson’s ratio | 0.35 | 63 |

| G | Shear modulus, Pa | 4.87 × 106; 1.08–4.32 × 108; | 50, 51 |

| Forced slip speed, m⋅s−1 | 5 × 10−9; 5 × 10−12 | — | |

| Forced slip speed, m⋅s−1 | 1 × 10−8; 1 × 10−11 | — | |

| L | Slip surface length, m | 1,000; 500 | — |

| Scaled slip surface length | 0.1; 2–8 | — | |

| Nucleation distance, m | 2,500; 250 | — | |

| Background effective stress, Pa | 6 × 104; 5.3 × 105 | — |

Values on the left and right of the semicolon correspond to the slow-moving and catastrophic landslide runs, respectively. Subscripts rw, rs, and rn correspond to rate-weakening, rate-strengthening, and rate-neutral.

Results

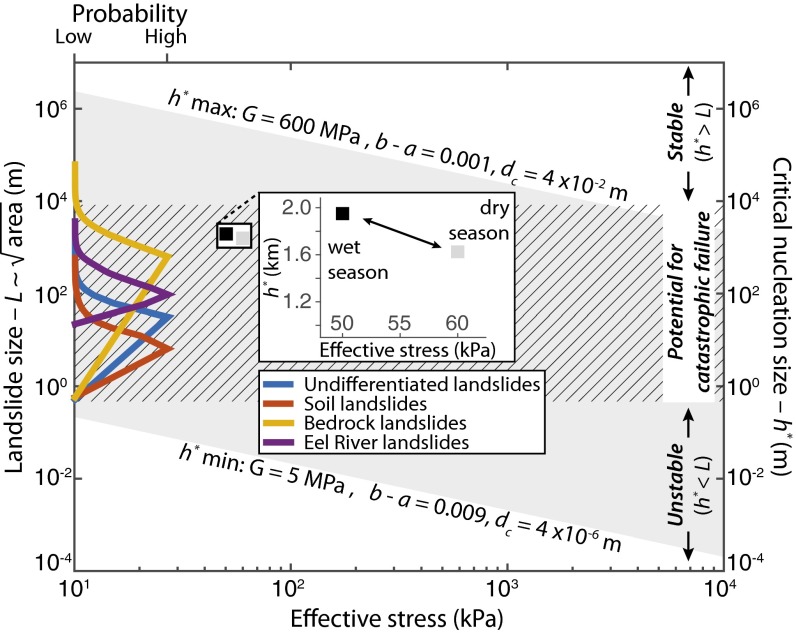

Fig. 2 shows the parameter space for combined with a typical range of size and effective stress values for a global distribution of landslides. For a given effective stress, can be either larger or smaller than a typical landslide dimension; hence, this first-order analysis implies that rate-weakening landslides can display both stable and unstable sliding. Paradoxically, Eq. 4 also predicts that landslides driven by transient stress perturbations are somewhat less prone to runaway acceleration during wet periods when motion is most common, because increases with decreases in effective stress (Fig. 2, Inset). This finding can be particularly important for understanding the behavior of landslides that are at or near the critical nucleation length.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of critical nucleation lengths and sizes of landslides. The shaded gray area spans the full parameter space for . Values for maximum and minimum are indicated on the plot. Other parameters are listed in Table S1. Diagonal lines and kernel density probabilities correspond to measured range of landslide size, calculated as sqrt(landslide area), for a global inventory of soil, rock, undifferentiated landslides (28) and for slow-moving landslides in the Eel River catchment, Northern California (5). Sliding mode corresponds to stable (i.e., noncatastrophic, bigger than slipping region) and unstable (i.e., catastrophic, slipping region bigger than ). The range of values indicates that for a given effective stress, rate-weakening landslides can display both stable and unstable sliding. Inset shows how seasonal changes in pore-water pressure affect .

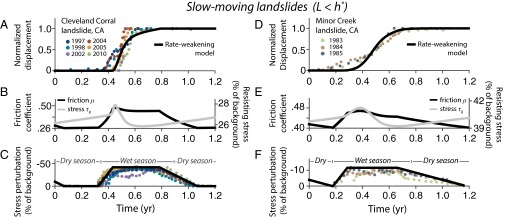

To investigate seasonally active slow-moving landslides, stress perturbations were chosen to mimic precipitation-induced seasonal fluctuations in pore-water pressure measured at the Cleveland Corral (29) and Minor Creek landslides (30) in Northern California (Fig. 3 and Materials and Methods). These landslides display distinct seasonal velocity changes, with periods of increased velocity that correspond to periods of elevated pore-water pressures. Numerous other landslides in this region (31, 32), and elsewhere that similar environmental conditions (i.e., tectonics, lithology, and climate) prevail, display similar displacement patterns and are likely driven by comparable stress perturbations (3, 33, 34).

Fig. 3.

Model simulations for slow-moving landslides. Field data are broken into individual water years (starting October 1) and condensed into a 1-y period. (A and D) Normalized displacement time series for field-based measurements and rate-weakening model plotted at a representative node. Displacement is normalized by yearly maximum to make direct comparisons. (B and E) Friction coefficient, μ, and normalized resisting stress, , defined as the friction coefficient times the effective stress and divided by the background effective stress (i.e., dry season maximum). (C and F) Transient stress perturbation divided by background effective stress. The stress perturbations correspond to the transient reduction in effective stress that results from an increase in pore-water pressure. Other parameters are listed in Table S1. Data digitized from ref. 30 and the US Geological Survey.

Our model successfully reproduces the general patterns of displacement that are observed. Each modeled landslide displays an instantaneous velocity increase in response to the imposed decrease in effective stress (Fig. 3 and Movie S1). The ensuing period of acceleration is followed by a longer period of deceleration. Changing the rate-dependent properties (Eq. 1) results in slight differences in the timing and magnitude of the seasonal displacement (Fig. S1). These relatively minor changes suggest that the frictional rate dependence plays a secondary role in governing the overall landslide behavior in this regime. Importantly, we used the field data to determine only the timing and magnitude of realistic stress perturbations; we did not calibrate the parameters in our highly idealized model to optimize the fit to displacement data.

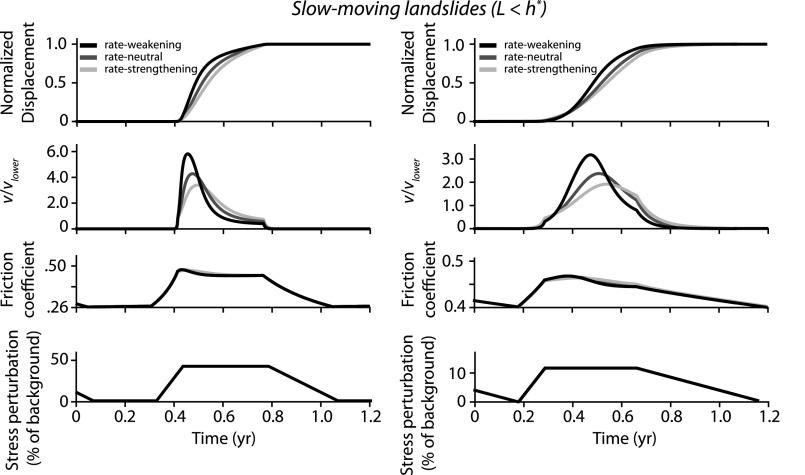

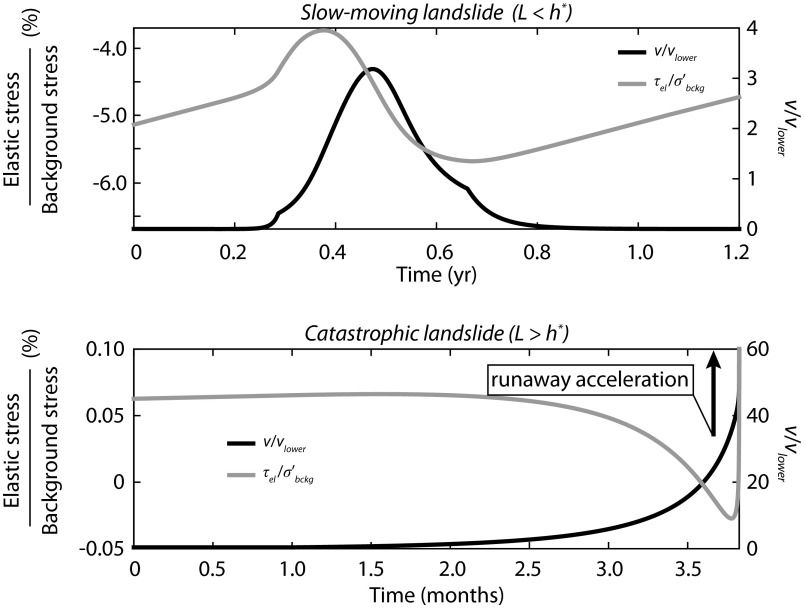

Fig. S1.

Rate-dependent material controls on modeled landslide behavior. Cleveland Corral-like stress perturbations are on the left and Minor Creek-like stress perturbations are on the right. Model simulations performed with rate-weakening material have a nominal . All model parameters except for a are the same as those shown in Fig. 3. See Table S1 for additional parameters. Normalized displacement corresponds to the displacement divided by the maximum displacement. is the velocity normalized by the fixed slip-rate boundary condition. Stress perturbations corresponds to the transient reduction in effective stress that results from an increase in pore-water pressure; these values are normalized by the background effective stress for each landslide. Note only minor differences in behavior occur as a result of changes in frictional properties.

Further insight comes from examining the time-dependent friction coefficient μ (Eq. 1), and the resisting stress (defined as effective stress multiplied by the friction coefficient), at fixed locations along the landslide base (Fig. 3 B and E). During periods of enhanced seasonal motion, the resisting stress and friction coefficient generally track the landslide velocity due to the “direct effect,” which describes the instantaneous strength increase that accompanies faster sliding (35). This strength increase acts to overcome the strength decrease due to the reduction in effective stress. When the effective stress stabilizes at a constant, lower value during the wet season, the landslide velocity continues to evolve and elastic stress transmission contributes to maintaining the force balance (Fig. S2A).

Fig. S2.

Normalized elastic stress (light, left axis) and normalized velocity (dark, right axis) plotted at a representative node. Model parameters for the slow-moving landslide correspond to the Minor Creek-like results shown in Fig. 3. Model parameters for the catastrophic landslide correspond to Fig. 4. The elastic stress is normalized by the background effective stress at each landslide. For the slow-moving landslide calculations, the elastic stress is small at all time steps and changes during transient slip periods to maintain the force balance along the sliding surface. Note the elastic stress is less than zero at all time steps as a result of the fixed slip-rate boundary conditions. For the catastrophic landslide calculations the elastic stress is negligible until runaway acceleration, at which point the resisting stress cannot balance the driving stress.

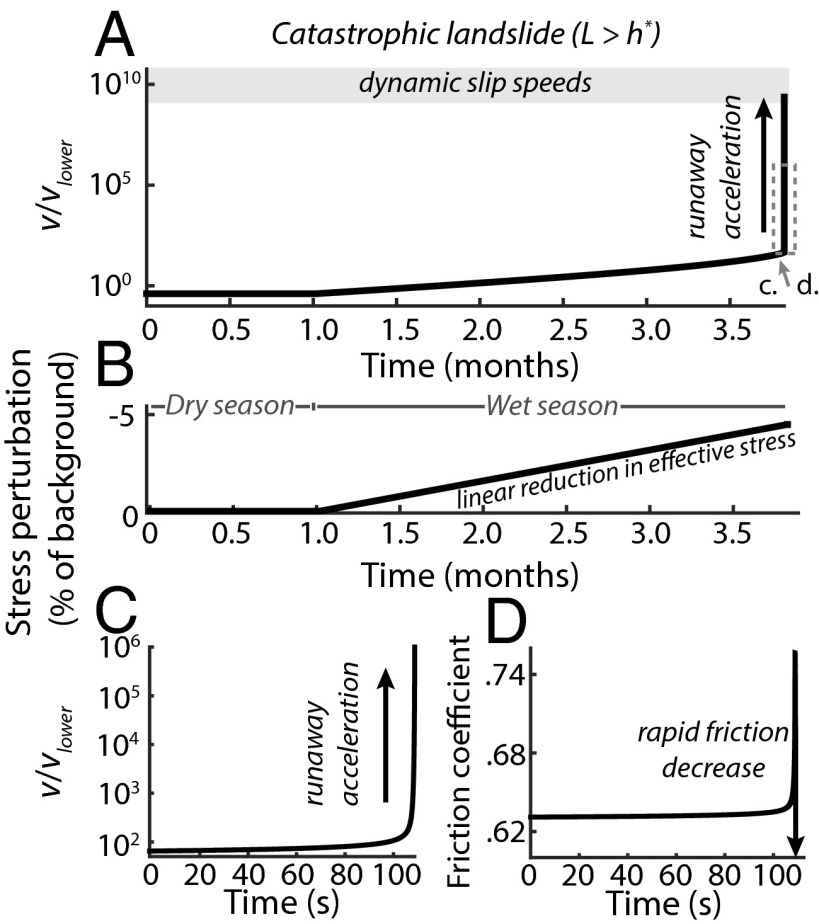

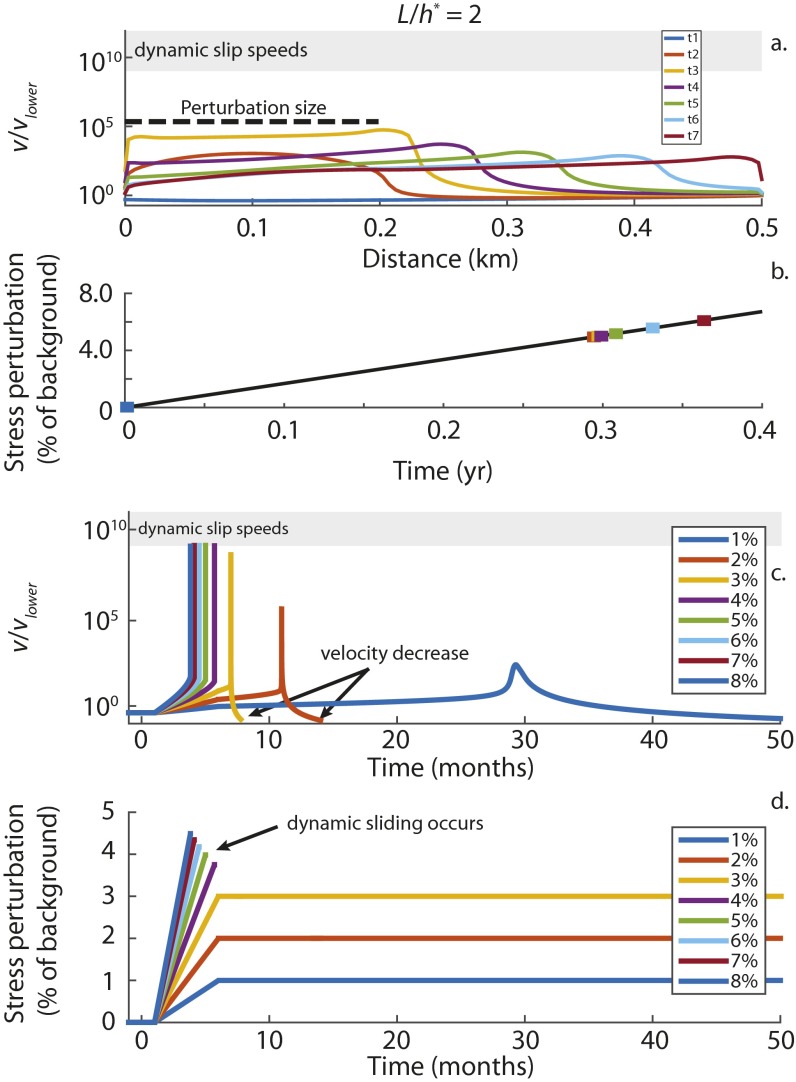

To explore how transient stress perturbations can trigger runaway acceleration and catastrophic failure, we ran simulations with rate-weakening material and values of between 2 and 8. We imposed a gradual reduction in effective stress to simulate deep pore-water pressure changes forced by surface rainfall (Fig. 4B and Materials and Methods). Acceleration begins gradually as the pore-water pressure rises and the effective stress decreases, with slow motion persisting for several months before a rapid transition to runaway acceleration (Fig. 4 and Movie S2). During this period of slow motion, the friction coefficient exhibits only a subtle increase due to the direct effect. As the landslide approaches catastrophic failure, rapid velocity increases drive further increases to the friction coefficient until , which subsequently causes a reduction in frictional strength that cannot balance the driving stress (Fig. 4D and Fig. S2B). The modeled displacement pattern is similar to the creep-to-failure motion that has been observed before several catastrophic landslides (Fig. S3) (24).

Fig. 4.

Model simulation for catastrophic landslide with . (A) Velocity time series plotted at a representative model node and divided by the lower boundary slip speed, vlower. Shaded gray area signifies speeds at which inertial effects become significant (21). (B) Transient stress perturbation divided by background effective stress (i.e., dry season maximum). The stress perturbation corresponds to the transient reduction in effective stress that results from an increase in pore-water pressure. (C) Normalized velocity during the final seconds approaching runaway acceleration. (D) Friction coefficient, μ, during the final seconds approaching runaway acceleration. Friction coefficient rapidly increases and then rapidly decreases. Note that C and D show the time in seconds where 0 is the first time step corresponding to the zoomed-in region shown by the gray dashed rectangle in A. Other parameters are listed in Table S1.

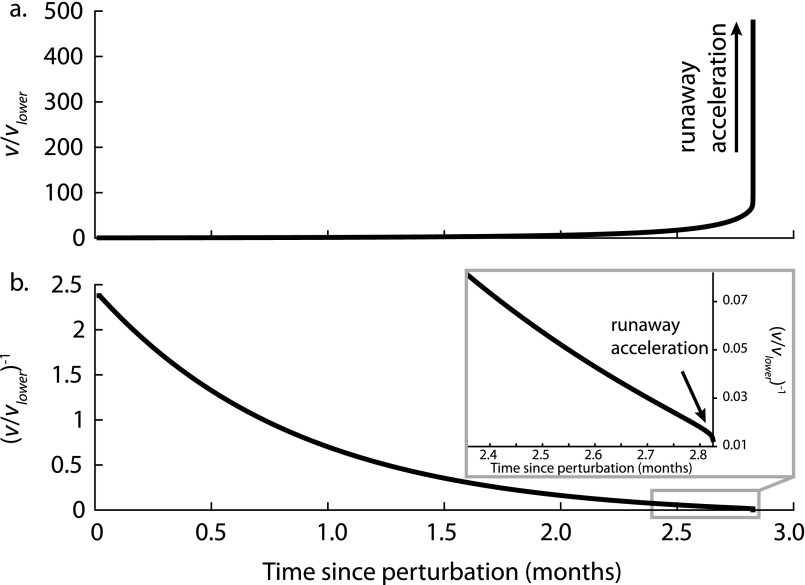

Fig. S3.

Creep-to-failure motion for catastrophic landslide model simulations. Model parameters are chosen to match the results shown in Fig. 4. (A) Normalized velocity time series shows slow acceleration for several months before a transition to rapid acceleration and catastrophic failure. (B) Normalized inverse velocity time series plotted to make comparisons with field measurements of creep-to-failure behavior (24).

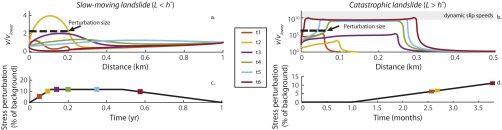

In model investigations of spatially heterogeneous stress perturbations along the landslide body, we also triggered motion using localized stress perturbations. These stress perturbations can be interpreted as resulting from pore pressure changes facilitated by preferential flow paths (e.g., macropores and deformation cracks) (36). For model runs in the slow-sliding regime, local stress perturbations trigger seasonal motion that spreads along the sliding surface (Fig. S4A and Movie S3). The highest peak velocity and cumulative displacement occur along the section of the slip surface subjected to the stress perturbation. Similar behavior occurs for model runs in the dynamic sliding regime, up until the point of catastrophic failure (Fig. S4B).

Fig. S4.

Spatial evolution of modeled velocity in response to local stress perturbations (i.e., stresses are only perturbed on a small section of the sliding surface). Model parameters for the slow-moving landslide model correspond to the Minor Creek-like model shown in Fig. 3. Model simulations for the catastrophic landslide model performed with rate-weakening material and . Horizontal dashed line shows the spatial dimensions of the slip surface subjected to the stress perturbation. Velocity changes drive motion along the entire landslide due to elastic stress-transmission. Colored squares in (C and D) correspond to stress and time position of the colored velocity lines in (A and B). Shaded gray area in B signifies runaway acceleration (21). Note several of the time steps shown in D are hidden beneath the rightmost symbol, due to their proximity in time. Stress perturbation corresponds to the transient reduction in effective stress that results from an increase in pore-water pressure. The stress perturbation is normalized by background effective stress for each landslide.

Discussion and Concluding Remarks

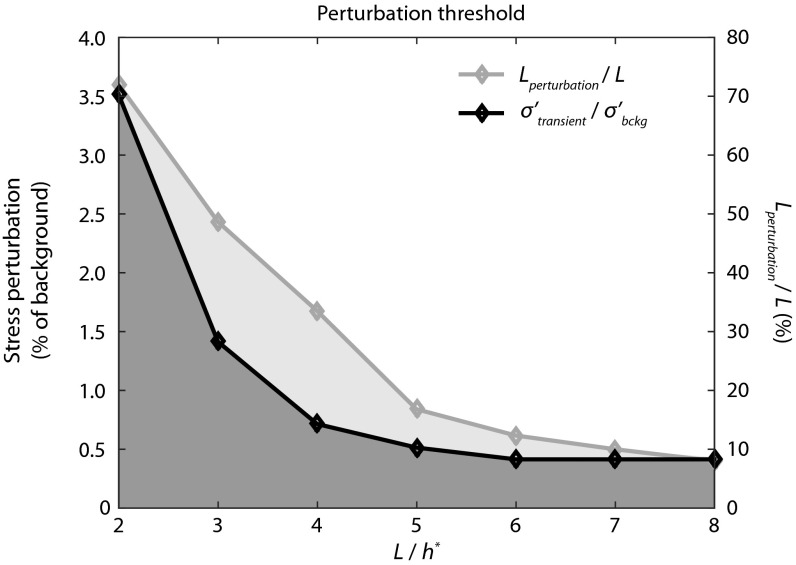

Although the expression for given in Eq. 4 provides a first-order estimate for the length scale that determines failure mode, previous studies on tectonic faults have shown that multiple length scales can be relevant to earthquake nucleation, including those arising from additional physical interactions, such as dilatancy, and from geometrical and material irregularities (7, 12). Similar to tectonic faults, there are likely multiple length scales relevant to landslide failure mode, some of which are expected to vary in time (Fig. 2). Furthermore, landslide failure mode may also depend on the magnitude of the stress perturbation when the slip surface dimensions are close to the critical nucleation length. For example, model simulations with display slow sliding if either the stress perturbations are of the background effective stress, or they occur along a patch size that is of the sliding surface length L (Figs. S5 and S6). These thresholds decrease as the slip surface length is increased to several times the critical nucleation length (Fig. S6). An examination of the sensitivity of landslide behavior to multiple relevant length scales (e.g., landslide length and width) would require a more advanced treatment than the idealized one-dimensional model presented here. The increasing availability of high-resolution digital elevation models (e.g., lidar) and ground surface deformation data [e.g., Synthetic Aperture Radar Interferometry (InSAR)] will enable future studies to address more complicated landslide geometries.

Fig. S5.

Examples of slow-sliding simulations for modeled landslides despite being in the catastrophic landslide regime (i.e., ). (A) Normalized velocity for spatially localized stress perturbation when perturbation is below spatial threshold value (see right vertical axis in Fig. S6). Perturbation size (referred to as “” in Fig. S6) corresponds to the area of the slip surface subjected to the stress perturbation shown in B. (B) Stress perturbation corresponds to the transient reduction in effective stress that results from an increase in pore-water pressure. The stress perturbation is normalized by background effective stress. Colored squares in B correspond to stress and time position of the colored velocity lines in A. (C) Normalized velocity time series as function of stress perturbation magnitude. Perturbation magnitude (referred to as “Stress perturbation” in Fig. S6) is shown as a percentage in the figure legend and is defined as the maximum transient pore-water pressure normalized by the background effective stress. Model run ends when dynamic sliding begins. Arrows labeled “velocity decrease” indicate that the slip surface speed decreases below the horizontal axis after the stress perturbation. (D) Stress perturbation corresponds to the transient reduction in effective stress that results from an increase in pore-water pressure.

Fig. S6.

Minimum magnitude and spatial dimension of stress perturbations required to trigger catastrophic failure. Left vertical axis and black line show the normalized magnitude of the transient pore-water pressure required to trigger failure (i.e., any perturbation greater than the listed value will trigger catastrophic failure). In these model runs the stress perturbation is imposed along the entire sliding surface. Right vertical axis and gray line show the spatial dimensions of the stress perturbations () relative to the total landslide length (L) required to trigger catastrophic failure (i.e., any perturbation greater than the listed value will trigger catastrophic failure). In these model runs the perturbation to the pore-water pressure lowers the effective stress by 8% relative to background levels. We have color-coded the area below and above the curves to correspond to particular sliding regimes. Model runs in the dark gray region always results in slow sliding. Model runs in the light gray shaded region correspond to dynamic sliding for the left axis and slow sliding for the right axis. Model runs in the white shaded area always result in dynamic sliding. Note these sliding regimes will change if any of the rate and state friction parameters change. This figure shows that as increases, smaller perturbations are needed to trigger catastrophic failure.

When driven by realistic stress perturbations along the sliding surface, our model reproduces deformation patterns observed at landslides and provides insights into the mechanisms that control the mode of failure. Landslides composed of rate-weakening material display both slow (seasonal) and dynamic (catastrophic) sliding, with the character depending on the size of the sliding surface, or slip patch, relative to the critical nucleation length. This is directly analogous to behavior that is well established in fault mechanics, where a similar variety of slip modes is observed (12, 13). Given that slow-moving landslides occur in a wide variety of lithologic units, we expect many of them to contain rate-weakening material. However, we hypothesize that slow-moving landslides containing rate-weakening material rarely fail catastrophically because the spatial dimensions of their most actively slipping regions are smaller than the critical nucleation length (Fig. 2).

Although our modeling framework provides a mechanistic interpretation for the boundaries between stable and unstable sliding regimes, the detailed processes by which landslides transition from one regime to the other are less certain. One potential scenario involves a decrease in the characteristic slip distance for the evolution of frictional contacts as a result of shear localization (35, 37), which in turn decreases relative to L. Alternatively, we hypothesize that the spatial dimensions of the landslide, or slip patch, may evolve in time until . Landslides tend to grow until they span from hilltops to channel bottoms (16, 37, 38). Furthermore, landslides can display distinct kinematic elements that are defined empirically by differences in the timing of motion along the landslide body (39). These differences in motion may reflect the presence of temporary slip barriers (i.e., strong patches) that are able to contribute disproportionate resistance to the downslope translation of the landslide material (40). This suggests that landslides that exhibit complex motion, consisting of an ensemble of smaller slip patches that can result from heterogeneity in basal strength, may be less likely to fail catastrophically compared with landslides that exhibit more uniform motion. The Cleveland Corral landslide, which is located within 3 km of two large landslides that failed catastrophically, may provide an opportunity to test this hypothesis. In 1997 the US Geological Survey (USGS) installed a long-term monitoring station in an attempt to capture the transition from slow motion to catastrophic failure (29). So far the landslide has displayed only seasonal displacement, but when it moves it typically displays complex, nonuniform motion along its entire body. Importantly, the landslide has developed new shear margins and kinematic elements over the past two decades (41). Our results imply that further landslide growth, as gauged by an evolution toward more uniform motion, may presage catastrophic failure.

Materials and Methods

Rate and State Model.

Fig. 1 displays a schematic diagram of the model domain, which parallels well-established rate and state descriptions for the behavior of tectonic faults (12, 13). We focus on how perturbations to the momentum balance cause variations in the slip velocity v. Accordingly, Eq. 1 is used to capture the empirically based logarithmic dependence of the friction coefficient μ on slip velocity v (35); this necessitates that modeled sliding velocities remain finite at all times, although sliding can proceed at rates that are negligible in comparison with those imposed at the boundaries. The sliding surface is forced to slip at a small rate for and at for , where we set for all calculations shown here (Table S1 and Fig. 1). These boundary conditions can be interpreted to represent steady long-term motion induced by loading due to headscarp slumping at the upper boundary and toe erosion at the lower boundary. The slip-rate gradient is chosen to simulate velocity variations along the sliding surface that are commonly observed (22, 33). We recognize that many landslides display more complex slip gradients but neglect such complications here to focus upon the most essential underlying controls. For each model simulation, the sliding surface has constant gravitational driving stress, background effective stress, and frictional properties within the interval .

We use a grid spacing , which provides sufficient resolution for the Aging law (12), where

| [5] |

is the nucleation length scale for perturbation-induced slip transients (11, 42) and subscript corresponds to rate weakening. We solve Eqs. 1–3 as coupled first-order differential equations in v and θ using ODE solver routines in MATLAB. The elastic stresses are calculated in the Fourier domain where the transformed quantify satisfies

| [6] |

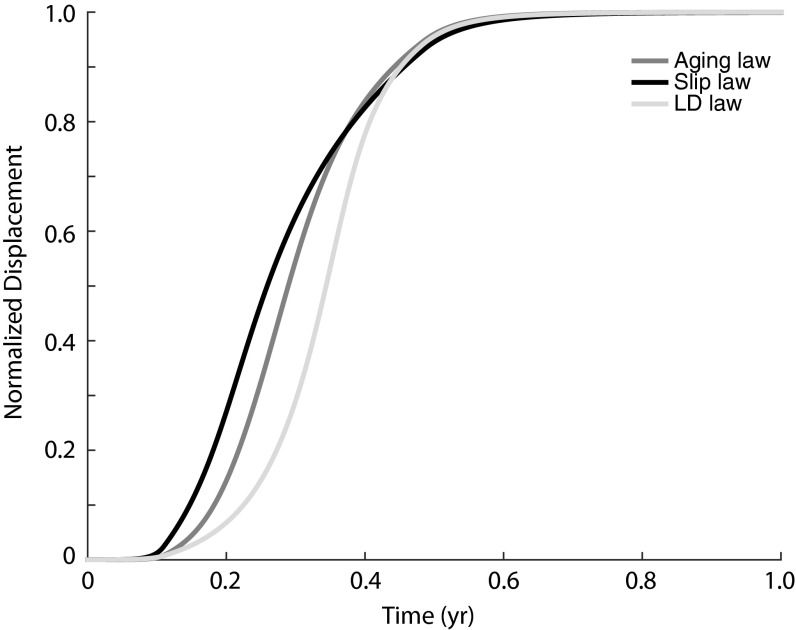

where n is the wavenumber. The forced-slip section is set to a total length of to prevent numerical error in the Fourier domain. To ensure that the initial conditions have minimal influence on the model results, model simulations are run to steady-state sliding before being subjected to stress perturbations. In addition, for the slow-moving landslide model we perturb the stress conditions over multiple consecutive years to confirm the model can reproduce the repeated seasonal velocity changes observed at real landslides (30, 32). Lastly, we explored two additional commonly used state evolution laws (see Supporting Information, Eqs. S1 and S2 and Fig. S7). We found only minor differences in predicted displacement patterns between each set of model simulations.

Fig. S7.

Normalized displacement (i.e., displacement/maximum displacement) for the Aging (medium gray), Slip (dark gray), and Linker–Dieterich (light gray) evolution laws. Note that minor differences in the timing of motion are of secondary importance in comparison with the overall agreement in displacement patterns.

Elastic Stresses During Landslides.

Significant insight has been gained into earthquake mechanics by modeling displacement along one-dimensional faults (i.e., continuous arrays of dislocations) with elasticity (20, 43). These models combine well-constrained laboratory measurements of friction with dislocation theory and fracture mechanics to quantify stress along a slip surface. However, the effects of elasticity are commonly ignored in landslide models because the material that overlies the landslide slip surface does not behave elastically over long timescales or for large displacements. However, elastic deformation can be significant for small displacement and strain over short timescales. Several studies have accounted for these effects to quantify key features of landslides, including landslide depth (17) and incipient motion (15, 16). Because our model simulations describe small displacements and gradients in slip rate over short distances, the incorporation of elastic effects is both reasonable and appropriate.

We account for elastic stress transmission due to nonuniform slip along the sliding surface. Fig. S2 shows that the elastic stress is relatively small at all time steps and only becomes large in the final moments leading up to runaway acceleration. For model simulations where , the elastic stress changes during periods of transient slip to account for changes in velocity and frictional strength along the slip surface (i.e., nonlocal accelerations). Thus, the elastic stress is able to compensate for rate-weakening friction and prevent runaway instability. However, when the elastic stress cannot compensate for the rate-weakening effects and the driving stress eventually exceeds the frictional strength, leading to runaway acceleration. Our findings suggest that elastic stress transmission provides an important control on landslide failure mode.

Slip Near a Free Surface.

The landslides we focus on are deep in comparison with the modeled displacement but shallow in comparison with their along-strike lengths. This geometrical configuration requires that additional terms be added to the integral of Eq. 3 to account for changes in shear and normal stress that arise from slip near a free surface (see equations 21–25 in ref. 16). Studies that have incorporated the free surface into their model simulations in other contexts have found that these effects produce fairly minor differences in the overall model predictions (12, 16). Similar to the results of these studies, our preliminary calculations with a more computationally challenging elastic formulation that imposes stress-free boundary conditions at the free surface result in changes to the predicted behavior that are of secondary importance to the overall displacement patterns that are our focus here.

Parameter Values.

Numerous laboratory investigations have calibrated rate and state friction parameters for a wide range of slip rates, stresses, and materials (35). However, there are no published rate and state friction parameters from laboratory experiments on landslide material at relevant in situ stress conditions. Because the slip surfaces of landslides and faults are both governed by frictional sliding (14), we select nominal rate and state parameter values from the fault and soil mechanics literature (Table S1) (18, 44–49). Because our focus here is on understanding the overall patterns of landslide motion, we consider small errors introduced by uncertainty in parameter values to be acceptable. We note that Lacroix et al. (26) back-calculated a and b using a slider block model to describe field-based measurements of a slow-moving landslide perturbed by a nearby earthquake and found highly unusual values that are 13 orders of magnitude smaller than those typically used (an error in their calculations implies that the values of a and b are actually 10 orders of magnitude lower than the values they published). We view these unusual parameter values with suspicion and suggest that they may be an artifact of their model formulation, which discounted potential effects of variations in effective stress and transient elastic coupling along the slip surface.

Several model parameters differ between our choices for the slow-moving landslide and catastrophic landslide calculations (Table S1). Parameters were primarily chosen so that the models produce displacement patterns that have been observed in field and remote sensing studies of landslides (24, 29, 30, 32). For the slow-moving landslide model runs, we use a larger that is consistent with field-based estimates of friction parameters on faults (35). We select that characterizes weak, clay-rich materials (45, 46, 48, 49) that are common to slow-moving landslides with well-developed slip surfaces (2). The shear modulus and shear wave speed are based on values measured for the Jurassic and Cretaceous Franciscan Complex, Northern California (50), a region well known for slow-moving landslide activity (5), and are notably lower than values reported for deep faults. We chose the length, effective stress, and forced-slip boundary conditions to approximate values from slow-moving landslides in Northern California (22, 29, 30).

For the catastrophic landslide calculations, we selected parameters that predict creep-to-failure motion similar to field observations (24). This required higher effective stress and lower (i.e., smaller ) and significantly lower forced-slip boundary conditions such that the landslide is effectively not moving until perturbed (Fig. 4 and Table S1). We use a that characterizes rock and soil materials (18, 44, 45, 48, 49). The shear modulus and shear wave speed are based on values measured in glacial tills that are prone to catastrophic landslides (51) [e.g., the March 2014 Oso landslide in Washington, which killed 43 people (52)]. Model simulations shown in Fig. 4 were run at a nominal scaled slip surface length . However, we performed additional model simulations with because the ratio has been found to control the failure mode along faults (12, 13, 53). Although dynamic motion occurred for , we did confirm an apparent stress perturbation size threshold that decreases with increasing (Fig. S6).

Stress Perturbations.

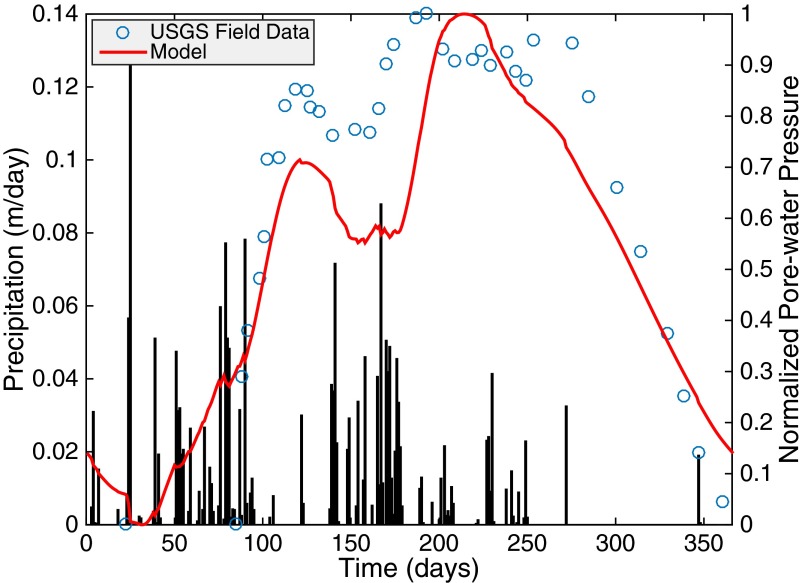

Stress perturbations due to transient pore-water pressure are simulated with spatial and temporal changes in effective normal stress. For the slow-moving landslide calculations, we approximate the timing, magnitude, and duration of transient pore-water pressure using a piecewise linear function that broadly captures the patterns of pore-water pressure change measured in deep piezometers at the Cleveland Corral (29) and Minor Creek landslides (30), Northern California. Pore-water pressures vary by of the background effective stress (i.e., dry season maximum) at Cleveland Corral and of the background effective stress at Minor Creek (Fig. 3 C and F). Field data were digitized from the USGS monitoring website (landslides.usgs.gov/monitoring/hwy50/yearly.php) and from data presented by Iverson and Major (30). Data are condensed into a 1-y period. For the catastrophic landslide calculations, we perturb the stress along the sliding surface using a linear function that increases by – of the background effective stress (Fig. 4B and Fig. S4D). In SI Materials and Methods we outline methods to calculate changes in pore-water pressure over shorter timescales and in locations where direct measurements are absent or scarce (Fig. S8).

Fig. S8.

Precipitation rate (black), measured pore-water pressure (circles), and calculated pore-water pressure (red) for the Cleveland Corral landslide in California. Pore-water pressure is calculated from the precipitation time series using Eqs. S3–S8. Pore-water pressure is normalized by the yearly maximum value. Pore-water pressure data were digitized from the USGS monitoring website (landslides.usgs.gov/monitoring/hwy50/yearly.php).

Forecasting Landslide Failure Mode.

Our theoretical treatment is not yet able to provide predictive insight in more realistic settings. However, our treatment illustrates a framework that can be extended to make these predictions in future studies. Currently, it is possible to broadly identify rate-dependent properties by examining historic landslide inventories. For example, regions with catastrophic landslides must display rate-weakening properties. However, our model framework cannot be used to differentiate material properties at slow-moving landslides. This will require additional data gathered from laboratory experiments on landslide material. Importantly, such experiments must be performed at the appropriate slip rates and stress levels for landslides so that the data can be used to calibrate the rate and state model parameters. Once the model parameters are known for representative landslides, geologic and geomorphic maps can be combined with published landslide inventories to identify areas with similar environmental conditions. This will enable assessments of whether landslides in particular areas are likely to display rate-weakening or rate-strengthening behavior.

Once the rate-dependent material properties are identified, the ratio of can be estimated using input from high-resolution topographic data. As mentioned in Discussion and Concluding Remarks, more work is needed to determine whether the length scale L that controls motion is most consistent with the total length, total width, or size of a slip patch within a distinct kinematic element. In Fig. 2 we use the square root of the landslide area, which is readily measured from topographic data. can be estimated using topographic data and hydrological models to approximate the effective stress along the slip surface.

Finally, to identify active landslides the ground surface deformation of landslide-prone regions must be monitored. Recent advances in remote sensing techniques, such as InSAR and pixel offset tracking, alongside greater availability of space-borne observations, now enable high-resolution spatial and temporal measurements that can be used to quantify hillslope deformation over entire mountain ranges. Combining these measurements with topographic data and the theoretical framework presented here may enable us to forecast the occurrence, failure mode, and timing of landslide events.

SI Materials and Methods

Additional Model Details.

Two main state evolution laws are used in rate and state friction models. The first, called the Aging (or Dieterich) law (Eq. 2) exhibits healing (i.e., increasing μ) during stationary contact. The second, called the Slip (or Ruina) Law, is defined by

| [S1] |

which exhibits no healing during stationary contact. When sliding conditions are near steady state (i.e., ), these laws have the same asymptotic behavior and yield predictions with only very slight differences (54). However, when conditions are far from steady state the predictions of these laws begin to differ significantly. Alternative treatments have been designed to account specifically for variations in frictional strength due to changes in effective stress, although relatively few laboratory studies have explored this behavior (44, 55, 56). To account for the condition of variable effective normal stress , Linker and Dieterich (44) propose that

| [S2] |

where the constant (57). Sliding induced variations in normal stress may be particularly important in governing fault stability along heterogeneous surfaces (56).

Because our idealized model is primarily designed to capture the broad qualitative patterns of landslide behavior, each of the Aging, Slip, and variable effective stress (LD) evolution laws are acceptable for our purposes. To demonstrate that our primary results are not biased by the choice of state evolution law, we performed several model runs using each law. As expected, we find only minor differences in predicted displacement patterns between each set of simulations (Fig. S7). For computational efficiency, we adopt the Aging law for all calculations shown in the main text.

Pore-Water Pressure in a Landslide Body.

In this paper we approximate pore-water pressure changes that trigger landslide motion using a simple linear function that captures the broad patterns measured in a landslide body (Figs. 3 C and F and 4B and Materials and Methods). Such pore-water pressure measurements within active landslides are rare, and the degree to which they provide a faithful representation of conditions along the sliding surface can be uncertain. Moreover, our simplified approach ignores hydrologic changes that can influence landslide behavior over daily to weekly timescales. To approximate changes in pore-water pressure over shorter timescales and in locations where direct measurements are absent or scarce, we can apply well-established pore-water pressure diffusion models, which describe changes in pore-water pressure that propagate by vertical diffusion from the ground surface to the basal sliding surface (30, 58–60). Several studies have used the diffusion equation to calculate pore-water pressure in a landslide but have incorporated a variety of surface boundary conditions to mimic the pressure change from rainfall at the ground surface. These boundary conditions have included a sinusoidal change to simulate seasonal rainfall (58), a step change to simulate strong pressure changes (32), and a response function to capture different rainfall patterns (61).

Here we outline a Green’s function method for solving the diffusion equation using precipitation time series as the surface boundary condition. In one dimension, the diffusion equation for pore-water pressure change at depth is described by

| [S3] |

where z is depth measured downward from the surface, D is the effective hydraulic diffusivity of the soil, and t is time. For simplicity, consider a case in which the precipitation rate distribution changes the boundary condition for pore-water pressures at the ground surface () such that this condition can be specified as

| [S4] |

where is the time series of surface pore-water pressures, s is a scaling factor that is empirically calibrated, and is the precipitation rate time series. The diffusion equation has a solution for the one-dimensional problem given transient surface boundary conditions

| [S5] |

where integral on the right side of this equation is the convolution integral. A solution to this equation can be obtained in the Fourier domain by

| [S6] |

| [S7] |

| [S8] |

where is the inverse Fourier transform operation.

Eq. S8 gives the transient component of the pore pressure acting on the sliding surface at depth H. Because diffusion is a linear process, we can obtain the total pore-water pressure by adding the background pore-water pressure to this deviation (the background pore pressure, , should be determined empirically if possible but should be close to , where g is gravity and is the density of water) for saturated conditions in which the water table is close to the surface. Note that the coordinate system is oriented parallel and perpendicular to the topographic surface, which is parallel to the landslide base. Importantly, in this formulation we ignore many details of infiltration and unsaturated flow and assume that precipitation rate, in some simple way, can be scaled to changes in pore-water pressure at a particular datum. In our future work we will implement this approach into our rate and state model. Fig. S8 shows rainfall, measured pore-water pressure, and calculated pore-water pressure for the deep piezometer at the Cleveland Corral landslide in California. The one-dimensional diffusion model does an adequate job at capturing transient changes in pore-water pressure that are used to drive landslide behavior.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Isaac Larsen for sharing data. We also thank two anonymous reviewers and editor Douglas W. Burbank for helpful reviews and comments. This work was supported by US Department of Energy Grant DE-FE0013565 (to A.W.R.) and NASA Grant 10-ESI10-0010 (to J.J.R.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1607009113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Iverson RM, et al. Acute sensitivity of landslide rates to initial soil porosity. Science. 2000;290(5491):513–516. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5491.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang G, Suemine A, Schulz WH. Shear-rate-dependent strength control on the dynamics of rainfall-triggered landslides, Tokushima prefecture, Japan. Earth Surf Process Landf. 2010;35:407–416. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angeli MG, Gasparetto P, Menotti RM, Pasuto A, Silvano S. A visco-plastic model for slope analysis applied to a mudslide in Cortina d’Ampezzo, Italy. Q J Eng Geol Hydrogeol. 1996;29:233–240. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iverson RM. Regulation of landslide motion by dilatancy and pore pressure feedback. J Geophys Res. 2005;110:F02015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mackey BH, Roering JJ. Sediment yield, spatial characteristics, and the long-term evolution of active earthflows determined from airborne lidar and historical aerial photographs, Eel River, California. Geol Soc Am Bull. 2011;123:1560–1576. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keefer DK, Johnson AM. Earth Flows: Morphology, Mobilization, and Movement. US Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Segall P, Rice JR. Dilatancy, compaction, and slip instability of a fluid-infiltrated fault. J Geophys Res. 1995;100(B11):22155–22171. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gabet EJ, Mudd SM. The mobilization of debris flows from shallow landslides. Geomorphology. 2006;74:207–218. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Segall P, Rubin AM, Bradley AM, Rice JR. Dilatant strengthening as a mechanism for slow slip events. J Geophys Res. 2010;115(B12) doi: 10.1029/2010JB007449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schulz WH, McKenna JP, Kibler JD, Biavati G. Relations between hydrology and velocity of a continuously moving landslide—Evidence of pore-pressure feedback regulating landslide motion? Landslides. 2009;6(3):181–190. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dieterich JH. Earthquake nucleation on faults with rate-and state-dependent strength. Tectonophysics. 1992;211:115–134. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubin AM. Episodic slow slip events and rate-and-state friction. J Geophys Res. 2008;113(B11) doi: 10.1029/2008JB005642. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skarbek RM, Rempel AW, Schmidt DA. Geologic heterogeneity can produce aseismic slip transients. Geophys Res Lett. 2012;39(21) doi: 10.1029/2012GL05376. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomberg J, Bodin P, Savage W, Jackson ME. Landslide faults and tectonic faults, analogs?: The Slumgullion earthflow, Colorado. Geology. 1995;23(1):41–44. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martel S. Mechanics of landslide initiation as a shear fracture phenomenon. Mar Geol. 2004;203(3–4):319–339. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Viesca RC, Rice JR. Nucleation of slip-weakening rupture instability in landslides by localized increase of pore pressure. J Geophys Res. 2012;117(B3) doi: 10.1029/2011JB008866. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aryal A, Brooks B, Reid ME. Landslide subsurface slip geometry inferred from 3-D surface displacement fields. Geophys Res Lett. 2015;42(5):1411–1417. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dieterich JH. Modeling of rock friction: 1. Experimental results and constitutive equations. J Geophys Res. 1979;84(B5):2161–2168. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruina A. Slip instability and state variable friction laws. J Geophys Res. 1983;88(B12):10359–10370. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Segall P. Earthquake and Volcano Deformation. Princeton Univ Press; Princeton: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rice JR. Spatio-temporal complexity of slip on a fault. J Geophys Res. 1993;98(B6):9885–9907. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Handwerger AL, Roering JJ, Schmidt DA, Rempel AW. Kinematics of earthflows in the Northern California Coast Ranges using satellite interferometry. Geomorphology. 2015;246:321–333. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chau K. Landslides modeled as bifurcations of creeping slopes with nonlinear friction law. Int J Solids Struct. 1995;32(23):3451–3464. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Helmstetter A, et al. Slider block friction model for landslides: Application to Vaiont and La Clapiere landslides. J Geophys Res. 2004;109(B2) doi: 10.1029/2002JB002160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sleep NH. Deep-seated downslope slip during strong seismic shaking. Geochem Geophys Geosyst. 2011;12(12) doi: 10.1029/2011GC003838. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lacroix P, Perfettini H, Taipe E, Guillier B. Coseismic and postseismic motion of a landslide: Observations, modeling and analogy with tectonic faults. Geophys Res Lett. 2014;41(19):6676–6680. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rice J, Ruina A. Stability of steady frictional slipping. J Appl Mech. 1983;50(2):343–349. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larsen IJ, Montgomery DR, Korup O. Landslide erosion controlled by hillslope material. Nat Geosci. 2010;3:247–251. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reid M, et al. Debris-flow initiation from large, slow-moving landslides. In: Rickenmann D, Chen CL, editors. Debris-Flow Hazards Mitigation: Mechanics, Prediction, and Assessement. Millpress; Rotterdam: 2003. pp. 155–166. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iverson RM, Major JJ. Rainfall, ground-water flow, and seasonal movement at minor creek landslide, northwestern California: Physical interpretation of empirical relations. Geol Soc Am Bull. 1987;99(4):579–594. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hilley GE, Bürgmann R, Ferretti A, Novali F, Rocca F. Dynamics of slow-moving landslides from permanent scatterer analysis. Science. 2004;304(5679):1952–1955. doi: 10.1126/science.1098821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Handwerger AL, Roering JJ, Schmidt DA. Controls on the seasonal deformation of slow-moving landslides. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2013;377:239–247. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malet JP, Maquaire O, Calais E. The use of global positioning system techniques for the continuous monitoring of landslides: Application to the super-sauze earthflow (Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, France) Geomorphology. 2002;43:33–54. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simoni A, Ponza A, Picotti V, Berti M, Dinelli E. Earthflow sediment production and Holocene sediment record in a large Apennine catchment. Geomorphology. 2013;188:42–53. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marone C. Laboratory-derived friction laws and their application to seismic faulting. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci. 1998;26:643–696. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krzeminska D, Bogaard T, Malet JP, Van Beek L. A model of hydrological and mechanical feedbacks of preferential fissure flow in a slow-moving landslide. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci. 2013;17(3):947–959. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palmer AC, Rice J. The growth of slip surfaces in the progressive failure of over-consolidated clay. Proc R Soc Lond A Math Phys Sci. 1973;332:527–548. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giordan D, et al. Morphological and kinematic evolution of a large earthflow: The Montaguto landslide, southern Italy. Geomorphology. 2013;187:61–79. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baum RL, Fleming RW, Johnson AM. 1993. Kinematics of the Aspen Grove landslide, Ephraim Canyon, central Utah . Bulletin 1842 (US Geological Survey, Reston, VA)

- 40.Baum RL, Johnson AM. 1993. Steady movement of landslides in fine-grained soils; A model for sliding over an irregular slip surface. Bulletin 1842D (US Geological Survey, Reston, VA), pp D1–D28.

- 41.Aryal A, Brooks BA, Reid ME, Bawden GW, Pawlak GR. Displacement fields from point cloud data: Application of particle imaging velocimetry to landslide geodesy. J Geophys Res. 2012;117(F1) doi: 10.1029/2011JF002161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perfettini H, Ampuero JP. Dynamics of a velocity strengthening fault region: Implications for slow earthquakes and postseismic slip. J Geophys Res. 2008;113(B9) doi: 10.1029/2007JB005398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rubin A, Ampuero JP. Earthquake nucleation on (aging) rate and state faults. J Geophys Res. 2005;110(B11) doi: 10.1029/2005JB003686. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Linker M, Dieterich J. Effects of variable normal stress on rock friction: Observations and constitutive equations. J Geophys Res. 1992;97:4923–4940. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saffer DM, Marone C. Comparison of smectite-and illite-rich gouge frictional properties: Application to the updip limit of the seismogenic zone along subduction megathrusts. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2003;215:219–235. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ikari MJ, Saffer DM, Marone C. Frictional and hydrologic properties of clay-rich fault gouge. J Geophys Res. 2009;114(B5) doi: 10.1029/2008JB006089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Niemeijer AR, Vissers RL. Earthquake rupture propagation inferred from the spatial distribution of fault rock frictional properties. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2014;396:154–164. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Skempton A. Residual strength of clays in landslides, folded strata and the laboratory. Geotechnique. 1985;35(1):3–18. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tika TE, Vaughan P, Lemos L. Fast shearing of pre-existing shear zones in soil. Geotechnique. 1996;46:197–233. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brocher TM. 2005. Compressional and shear wave velocity versus depth in the San Francisco Bay Area, California: Rules for USGS Bay Area Velocity Model 05.0.0 (US Geological Survey, Reston, VA)

- 51.Allstadt K, Vidale JE, Frankel AD. A scenario study of seismically induced landsliding in seattle using broadband synthetic seismograms. Bull Seismol Soc Am. 2013;103:2971–2992. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iverson RM, et al. Landslide mobility and hazards: Implications of the 2014 Oso disaster. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2015;412:197–208. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu Y, Rice JR. Spontaneous and triggered aseismic deformation transients in a subduction fault model. J Geophys Res: Sol Ea. 2007;112:B09404. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ampuero JP, Rubin AM. Earthquake nucleation on rate and state faults—Aging and slip laws. J Geophys Res. 2008;113(B1) doi: 10.1029/2007JB005082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dieterich JH, Linker M. Fault stability under conditions of variable normal stress. Geophys Res Lett. 1992;19:1691–1694. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rice JR, Lapusta N, Ranjith K. Rate and state dependent friction and the stability of sliding between elastically deformable solids. J Mech Phys Solids. 2001;49:1865–1898. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Perfettini H. 2000. Frottement sur une faille: Influence des fluctuations de la contrainte normale. PhD thesis (Université de Paris, Paris)

- 58.Reid ME. A pore-pressure diffusion model for estimating landslide-inducing rainfall. J Geol. 1994;102(6):709–717. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Berti M, Simoni A. Field evidence of pore pressure diffusion in clayey soils prone to landsliding. J Geophys Res. 2010;115(F3) doi: 10.1029/2009JF001463. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Berti M, Simoni A. Observation and analysis of near-surface pore-pressure measurements in clay-shales slopes. Hydrol Processes. 2012;26:2187–2205. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Iverson RM. Landslide triggering by rain infiltration. Water Resour Res. 2000;36:1897–1910. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Power WL, Tullis TE. The contact between opposing fault surfaces at Dixie Valley, Nevada, and implications for fault mechanics. J Geophys Res. 1992;97(B11):15425–15435. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lambe TW, Whitman RV. 1969. Soil Mechanics. Series in Soil Engineering (Wiley, New York)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.