Abstract

Objective

To examine whether maternal low blood glucose (BG), low body mass index (BMI) and small stature have a joint effect on the risk of delivery of a small-for-gestational age (SGA) infant.

Design

Women from a perinatal cohort were followed up from receiving perinatal healthcare to giving birth.

Setting

Beichen District, Tianjin, China between June 2011 and October 2012.

Participants

1572 women aged 19–39 years with valid values of stature, BMI and BG level at gestational diabetes mellitus screening (gestational weeks 24–28), glucose challenge test <7.8 mmol/L and singleton birth (≥37 weeks’ gestation).

Main outcome measures

SGA was defined as birth weight <10th centile for gender separated gestational age of Tianjin singletons.

Results

164 neonates (10.4%) were identified as SGA. From multiple logistic regression models, the ORs (95% CI) of delivery of SGA were 0.84 (0.72 to 0.98), 0.61 (0.49 to 0.74) and 0.64 (0.54 to 0.76) for every 1 SD increase in maternal BG, BMI and stature, respectively. When dichotomises, maternal BG (<6.0 vs ≥6.0 mmol/L), BMI (<24 vs ≥24 kg/m2) and stature (<160.0 vs ≥160.0 cm), those with BG, BMI and stature all in the lower categories had ∼8 times higher odds of delivering an SGA neonate (OR (95% CI) 8.01 (3.78 to 16.96)) relative to the reference that had BG, BMI and stature all in the high categories. The odds for an SGA delivery among women who had any 2 variables in the lower categories were ∼2–4 times higher.

Conclusions

Low maternal BG is associated with an increased risk of having an SGA infant. The risk of SGA is significantly increased when the mother is also short and has a low BMI. This may be a useful clinical tool to identify women at higher risk for having an SGA infant at delivery.

Keywords: gestational diabetes screeing, body mass index, maternal stature, small for gestational age

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Community-based cohort study with a high participation rate.

The joint impact of maternal stature, body mass index and blood glucose level measured at gestational diabetes mellitus screening on the risk of small-for-gestational age has been for the first time examined.

The results were from Chinese women only and this may affect its generalisability.

Introduction

Small-for-gestational age (SGA) is used to describe fetuses who fail to achieve a specific anthropometric or weight threshold by a specific gestational age. Therefore, it may include some neonates who are born constitutionally small, but not with pathological growth restrictions.1 SGA infants, in general, are more likely to present with hypoglycaemia and less able to achieve the metabolic adaptation required at birth.2 They are at significant risk for perinatal mortality and morbidity and create a substantial strain on the healthcare system.3–8 Although most SGA infants go on to achieve appropriate catch-up growth by 2 years of age, ∼15% may not and most of these children continue to experience poor growth throughout childhood.9 In addition, compared to those born appropriate for gestational age, SGA infants are more likely to have poor cognitive or psychological outcomes10 11 and are at increased risk for insulin resistance, obesity and abnormal cardiovascular risk factors profile later in life.12–14

SGA is usually diagnosed by examining the birth weight (BW) with gestational age. Clinically, various population birthweight centiles, such as birth weight being less than the 3rd, 5th or 10th centile, have been used for diagnosis of SGA, but the 10th centile is commonly used as infant mortality is significantly higher below this cut-point.3 15 The impact of maternal characteristics on SGA has been intensively studied. Confirmed maternal risk factors for SGA include small maternal stature, low prepregnancy weight, Indian or Asian ethnicity, nulliparity, mother born SGA, cigarette smoking and drug use, and maternal medical history.16

Height is one of the important phenotypic traits in human beings. Mother's height reflects her genetic make-up and her metabolic needs during pregnancy.17 A mother's prepregnancy weight, or more accurately the prepregnancy body mass index (BMI), predicts her nutritional needs during pregnancy in regard to the immediate and future health of the mother and her infant.18 Generally, taller mothers will have relatively larger babies and shorter mothers will have relatively smaller babies at birth. Women with higher prepregnancy BMI are more likely to deliver heavier infants if energy intake is not restricted. Women with lower prepregnancy BMI are at increased risk of delivering lighter babies if energy intake is not proportionally increased to meet the needs of the pregnancy.18 19 Since a fetus obtains nutrients and energy only through the placenta, maternal nutrition and energy intake is critical. There is no doubt that maternal blood glucose (BG) levels play a significant and independent role in fetal development.20 Evidence indicates that women with higher levels of maternal BG or gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) are at increased risk for delivery of large-for-gestational age (LGA) infants and establishing glycaemic control early reduces the risk.21–23 However, the impact of low maternal BG level on fetal growth is not well understood. SGA infants are commonly hypoglycaemic at birth. It has been hypothesised that maternal hypoglycaemia may alter fetal glucose metabolism and, in turn, fetal growth.24 25

Most studies that have examined maternal BG with fetal outcomes seem in favour of this hypothesis26–29 even with different cut-offs used to establish low glucose levels. However, none of them have examined how the observed risk association interacts with other known maternal risk characteristics such as maternal BMI and stature.

In light of this, we explored the association of maternal BG level at GDM screening with risk of delivery of SGA neonates in a population-based perinatal cohort study, and examined how maternal BMI and stature influenced this association.

Methods

Participants

The data used in this study are from a perinatal cohort study conducted in the Beichen District of the city of Tanjin, China between June 2011 and October 2012. The Beichen District has a population of ∼600 000 people with about 2000 live births annually. The details of the design and data collection can be found elsewhere.30 In brief, all women with pregnancy in Beichen District registered in a primary hospital at around the 12th gestational week to receive prenatal care services. At ∼24–28 gestational weeks, they were invited to have 1 hour 50 g oral glucose challenge test (GCT) to screen for GDM and those whose GCT ≥7.8 mmol/L (140 mg/dL) further underwent a fasting 2 hour 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) for diagnosis of GDM. Two thousand three hundred and sixty-four women of Beichen District giving birth during the study time period were included at the beginning. After excluding multiple births (n=49), mother's age <19 years or >40 years old (n=9), gestational age <37 weeks (n=78), incomplete GCT measurements (n=41) and BG level at GCT 7.8 mmol/L (140 mg/dL) or higher (n=615), 1572 women with normal BG singleton birth were included in this report.

Information collected at GCT

One hour 50 g GCT for screening GDM was scheduled at the primary hospital at 24–28 weeks of gestation. BG was measured in 60 min after ingesting a 200 mL of 25% oral glucose solution. Height was self-reported to the nearest centimetre if known or measured at GDM screening test. Weight was measured at GDM screening test with woman wearing a light clothes without shoes to the nearest 0.1 kg. BMI was derived as the weight (kg) divided by height (m2). Maternal blood pressure was measured using a calibrated mercury sphygmomanometer, regular cuff size (unless obese) following a 5 min seated rest period.

Obstetric outcomes

Gestational age was calculated as the weeks+days between the date of giving birth and date of the last menstrual period. Infant sex was recorded as female or male. BW and length were measured in the delivery suite after the baby was dried but before breast feeding. BW was measured to the nearest 0.1 g using a digital scale and birth length was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a calibrated length-board with the baby in the recumbent position. Ponderal index was calculated as the ratio of BW to birth length (g/cm3). SGA was defined as BW below the 10th centile for the gender-specified Tianjin population.

Covariates

Maternal demographic information was collected by a questionnaire when women came to register for receiving the perinatal care services at approximately the 12th week of gestation. It included maternal age (years), ethnicity (Han vs other), education level (<9 vs ≥9 years), residence (urban vs rural), whether it is the first pregnancy (yes vs no), whether having given birth before (yes vs no), medical history, including liver disease, kidney disease, heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, tuberculosis, hyperthyroid, hypothyroid or any other diseases that may affect mother's and fetus' vital status during the pregnancy (yes vs no), and maternity insurance (with vs without).

Statistical analysis

The characteristics of participants were first compared by SGA status. Student's t-tests were used for continuous variables and χ2 tests were for categorised variables. OR and its 95% CI from logistic regression models were then used to evaluate the risk association of delivery of SGA infants with maternal BG level, BMI and stature measured at GDM screening. Maternal BG, BMI and stature were all divided by 1 SD before modelling. First, maternal BG, BMI or stature was entered into the model individually (model 1). Second, all three variables were entered into the model simultaneously (model 2). Third, apart from the three variables put in the model 2, the following potential confounding variables have been added into the model: maternal age, education attained, residence, medical history, reproductive history, maternal insurance, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and infant sex and gestational age (model 3). In a fourth model, however, only those covariates with p values of <0.2 from the model 3 were included into the model; they were maternal residence, insurance and diastolic blood pressure. To examine the joint effect of maternal BG, BMI and stature measured at the GDM screening test on the risk of SGA, we dichotomised these three variables as: maternal low BG (<6 mmol/L (<108 mg/dL)) or high BG (≥6 mmol/L (≥108 mg/dL)), low BMI (<24 kg/m2) or high BMI (≥24 kg/m2) and small stature (<160 cm) or large stature (≥160 cm). The later corresponds to the 75th centile standing height of Asian and/or Chinese women population.31 Studies that examined the impact of BMI measured at GCT on the risk of perinatal outcomes are few. However, prepregnancy BMI ≥23.5 kg/m2 is considered as high for Chinese women32 and BMI of 24.0–25.9 kg/m2 in Chinese women was found to be associated with the lowest risk of death.33 Therefore, BMI of 24.0 kg/m2 at GCT was used as the cut-off in this study. Table 1 shows the cut-offs for these three variables. Eight different groups were then identified and the sample size for each group is shown in table 2. Group 1 (ie, BG ≥6.0 mmol (≥108 mg/dL), BMI ≥24 kg/m2, stature ≥160 cm) was used as the reference with the covariates listed in model 4 being adjusted. Internal validation was carried out for the final model (model 4) using bootstrap resampling methods with 1000 replications to obtain receiver operating characteristic area under curve (ROC AUC) to check whether there are biased estimates. All statistical analysis was conducted using Stata-SE V.12 (StataCorp 2011. Stata Statistical Software: Release V.12. College Station, Texas, USA: StataCorp LP) with two-tailed tests and an α of 0.05 for statistical significance. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Boards of the Women and Children's Health Center in Tianjin, and Brock University and each participant provided an oral consent.

Table 1.

The cut-offs for maternal BG, BMI and stature

| Low | High | |

|---|---|---|

| Blood glucose | <6 mmol/L (<108 mg/dL) | ≥ 6 mmol/L (≥108 mg/dL) |

| Body mass index | <24 kg/m2 | ≥24 kg/m2 |

| Stature | <160 cm | ≥160 cm |

BG, blood glucose; BMI, body mass index.

Table 2.

The sample size for eight different groups

| Group | n | BG, mmol/L (mg/dL) | BMI, kg/m2 | Stature, cm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (ref) | 354 | ≥6 (≥108) | ≥24 | ≥160 |

| 2 | 179 | <6 (<108) | ≥24 | ≥160 |

| 3 | 250 | ≥6 (≥108) | ≥24 | <160 |

| 4 | 98 | <6 (<108) | ≥24 | <160 |

| 5 | 231 | ≥6 (≥108) | <24 | ≥160 |

| 6 | 127 | <6 (<108) | <24 | ≥160 |

| 7 | 156 | ≥6 (≥108) | <24 | <160 |

| 8 | 80 | <6 (<108) | <24 | <160 |

BG, blood glucose; BMI, body mass index.

Results

One hundred and sixty-four neonates (10.4%) were identified as SGA in this cohort. There were no statistical differences in maternal demographic variables between infants with and without SGA (table 3). Compared to mothers of infants without SGA, mothers of SGA infants were, on average, 2.1 cm shorter (160.8 vs 162.9 cm, p<0.001); their BMI was lower (24.0 vs 25.4 kg/m2, p<0.001); and BG was also lower (6.2 vs 6.3 mmol/L, p<0.05). There were no statistical differences in the proportion of male infants and mean level of gestational age, but no surprise to see that the mean levels of BW, length and Ponderal index were significantly lower in SGA infants.

Table 3.

Characteristics by SGA status

| Non-SGA (N=1408) | SGA (N=164) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers' demographic information | |||

| Age (years, means (SD)) | 26.6 (3.6) | 26.3 (3.4) | NS |

| Han ethnicity (%) | 92.1 | 92.7 | NS |

| Education ≥9 years (%) | 78.9 | 79.3 | NS |

| Rural residence (%) | 28.1 | 29.3 | NS |

| Maternal insurance (%) | 51.1 | 54.3 | NS |

| Previous disease history (%) | 3.6 | 4.9 | NS |

| Primiparity (%) | 84.6 | 87.2 | NS |

| Have never been pregnant (%) | 60.7 | 64.0 | NS |

| Mothers’ physical information measured at GCT | |||

| Height (cm, means (SD)) | 162.9 (4.8) | 160.8 (4.7) | <0.0001 |

| BMI (kg/m2, means (SD)) | 25.4 (3.5) | 24.0 (3.4) | <0.0001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg, means (SD)) | 108.2 (10.9) | 106.8 (10.6) | NS |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg, means (SD)) | 69.5 (7.5) | 69.2 (7.4) | NS |

| BG level (mmol/L, means (SD)) | 6.3 (0.9) | 6.2 (1.0) | <0.05 |

| Infants’ physical information measured at birth | |||

| Sex of male (%) | 50.0 | 51.2 | NS |

| Gestational age (weeks, means (SD)) | 39.2 (1.1) | 39.3 (1.1) | NS |

| Weight (g, means (SD)) | 3465.0 (367.1) | 2742.3 (224.7) | <0.0001 |

| Stature length (cm, means (SD)) | 50.3 (1.1) | 48.8 (2.1) | <0.0001 |

| Ponderal index (g/cm3, means (SD)) | 2.7 (0.2) | 2.4 (0.4) | <0.0001 |

BG, blood glucose; BMI, body mass index; GCT, glucose challenge test; SGA, small-for-gestational age.

Table 4 shows the ORs of SGA for 1 SD change in maternal BG, BMI and stature. The ORs (95% CI) of delivery of SGA infants were similar regardless of either maternal BG, BMI and stature were entered into the model individually (model 1) or simultaneously (model 2), but without adjustment for other potential confounding variables. With 1 SD level increase (model 2), the odds of having an SGA infant decreased ∼17% for maternal BG (OR (95% CI) 0.83 (0.70 to 0.98), p<0.05), 39% for BMI (0.61 (0.50 to 0.75), p<0.001) and 35% for stature (0.65 (0.54 to 0.77), p<0.001). The risk associations did not change when other potential confounding variables were modelled. The ORs of SGA were similar whether all covariates were forced into the model (model 3) or only those with p value <0.2 (model 4). The ROC AUC was about 68.4% and bootstrap 95% CIs were similar to those in model 4.

Table 4.

ORs of delivery of SGA neonates for 1 SD of maternal BG, BMI and stature at GDM screening test

| n | BG |

BMI |

Stature |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95 CI | OR | 95 CI | OR | 95 CI | ||

| Model 1 | 1572 | 0.844 | 0.721 to 0.988 | ||||

| 1475 | 0.609 | 0.498 to 0.744 | |||||

| 1570 | 0.640 | 0.541 to 0.757 | |||||

| Model 2 | 1475 | 0.827 | 0.699 to 0.979 | 0.613 | 0.501 to 0.750 | 0.647 | 0.543 to 0.770 |

| Model 3 | 1429 | 0.822 | 0.691 to 0.979 | 0.606 | 0.487 to 0.755 | 0.643 | 0.536 to 0.770 |

| Model 4 | 1464 | 0.825 | 0.696 to 0.977 | 0.571 | 0.461 to 0.707 | 0.631 | 0.528 to 0.754 |

| 0.694 to 0.980* | 0.448 to 0.727* | 0.525 to 0.756* | |||||

Model 1: BMI, BG or stature was entered into the model alone without any adjustment.

Model 2: BMI, BG and stature were entered into the model simultaneously.

Model 3: BMI, BG and stature were entered into the model simultaneously with adjustment for maternal age, disease history, maternal residence, insurance, blood pressures, reproductive history, education received, and infant's sex and gestational age.

Model 4: BMI, BG and stature were entered into the model simultaneously with adjustment for maternal residence, insurance and diastolic blood pressure.

*Bootstrap 95% CIs.

BG, blood glucose; BMI, body mass index; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; SGA, small-for-gestational age.

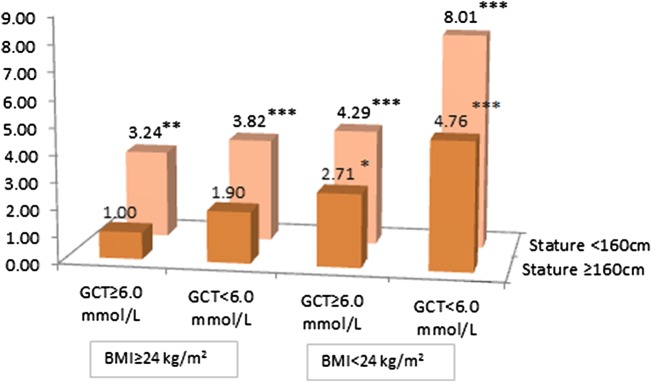

Figure 1 shows the ORs of SGA for the joint impact of maternal BG, BMI and stature. Maternal BG, BMI and stature were dichotomised with the cut-offs listed in table 1 and were categorised into eight groups (table 2). The ORs were obtained after adjusting for diastolic blood pressure, maternal residence and insurance as did in the model 4. Compared to the reference group (group 1), the ORs (95% CI) of SGA were 1.90 (0.87 to 4.14, p=0.106) for only having low BG, 2.71 (1.35 to 5.44, p<0.01) for only having low BMI and 3.24 (1.67 to 6.29, p<0.001) for only having small stature. When having any two of the lower items, the mothers had approximately four times higher odds of delivery of an SGA infant. If a mother was short, with low BMI and low BG, the OR (95% CI) for her to deliver an SGA infant was 8.01 (3.78 to 16.96, p<0.001) in comparison to the reference.

Figure 1.

ORs of delivery of a SGA neonate for dichotomous of maternal BMI, GCT and stature after adjustment for maternal residence, insurance and diastolic blood pressure. BMI, body mass index; GCT, glucose challenge test; SGA, small-for-gestational age.

Discussion

In this study, we found that, among women with an acceptable BG level measured at GDM screening in gestational weeks 24–28, lower maternal BG was independently associated with increased odds of having an SGA infant; this association was enhanced among mothers with low maternal BMI and/or small stature. Adjusting for other potential confounding variables did not change this association. Although maternal stature and BMI add to the risk, low levels of even acceptable maternal BG at GDM screening appear to play a role in the development of SGA.

Glucose as the fuel in metabolism is the most important nutrient for fetal growth, and a normal stable glucose level is essential for having a healthy baby at birth.20 The purpose of the GCT (1 hour 50 g) is to detect possible GDM among women who have no history of hyperglycaemia at early pregnancy. The results from a systematic review suggest that the cut-off of 1 hour 50 g GCT ≥7.8 mmol/L (140 mg/dL) is acceptable in screening for GDM; the pooled sensitivity and specificity were 0.74 and 0.77, respectively. However, it cannot replace the OGTT and combining the 1 hour 50 g GCT with other screening strategies for GDM is recommended.34 Therefore, when the GCT BG level is 7.8 mmol/L (140 mg/dL) or higher, women are referred to have an OGTT for diagnosis of GDM. Women whose BG level ≥7.8 mmol/L (140 mg/dL) at the GCT are more likely to have a larger baby at birth.35 We excluded those women from this study to avoid the potential bias on the observed risk association of SGA with low BG. Maternal low BG levels suggest a low energy supply capacity that may cause problems for normal fetal growth.36 The results from most studies that examined the association between levels of maternal BG at GCT and the risk of having an SGA infant at delivery demonstrate that the lower the BG level at GCT the higher is the risk of SGA infants at delivery. The BG cut-offs varied from study to study26–28 37–39 from <3.9 mmol/L (70 mg/dL) used by Melamed et al28 to <5.6 mmol/L (100 mg/dL) by Bienstock et al.26 All found a risk association with SGA except one with a cut-off of <4.9 mmol/L (88 mg/dL).27 Indeed, when different cut-offs are chosen, the sensitivity and specificity will vary. As even maternal BG level measured at random ≥6.1 mmol/L (110 mg/dL) is associated with an increased risk for GDM,40 we used GCT 6.0 mmol/dL (108 mg/dL) as the cut-off in this study to determine the risk of SGA. Our results indicated that the OR of SGA was approximately two times higher for women with GCT <6.0 mmol/L (108 mg/dL) alone in comparison with the reference group though it did not reach statistical significance. When maternal BG levels were entered into the model as a continuous variable, every 1 SD increase in maternal BG levels was associated with a 17% decreased OR of SGA. Considering this alongside the fact that the observed risk association changes with different cut-offs of GCT, it could be argued that the relationship between maternal BG levels and the risk of SGA could be similar to that between maternal BG levels and the risk for LGA, which is a continuous association.41 Normal pregnancy in general makes mothers slightly less insulin sensitive,42 so the metabolic needs for mother and fetus can be met with a relatively high level of BG. However, when maternal BG levels raise too high as in diabetes or GDM, it leads to fetal hyperglycaemia resulting in fetal over growth. In the opposite circumstance, when maternal glucose level is too low or too insulin sensitive, fetal hypoglycaemia results in fetal under growth.43 Thus, when the cut-off of low BG <6.0 mmol/L (108 mg/dL) is chosen, at least one more maternal characteristics below the cut-off is needed to reach a statistically significant conclusion (figure 1).

Maternal anthropometric characteristics such as small stature, low prepregnancy BMI or poor weight gain during the pregnancy are associated with SGA risk.16 18 19 Maternal size is considered the most important determinant of the fetal size. Small babies from short mother may not necessarily be pathologically growth restricted, but when other unfavourable factors, such as low maternal energy supply and/or poor fetal growth foundation, are added up, it may push the fetus towards SGA. Maternal prepregnancy BMI reflects the foundation for fetal growth, and low maternal prepregnancy BMI may allow less flexibility during pregnancy to address the demands of fetal growth44 while meeting the needs of the mother. Our previous work indicated that higher maternal BMI and elevated maternal glucose level significantly increase the odds of macrosomic infants at delivery.45 The data reported here appear to be the first study examining the combined effect of low maternal BG, low BMI and small stature on the risk of SGA. The results suggest that low maternal BG, low BMI and small stature have a synergistic effect on the odds of having an SGA infant at delivery. Using ‘small’ or ‘low’ can only describe the unfavourable but not the actual circumstances of the stature, BG level or BMI since women within each category could be healthy. Nevertheless, when a woman was categorised with three such unfavourable conditions, the odds of SGA was significantly higher compared to those who had none or fewer of them (figure 1). This may have potential importance in clinical practice, as it would allow the identification of women who, while having acceptable BG levels at GDM screening, have an increased risk of an SGA infant. Critically this is at a point in pregnancy where a nutritional intervention could still have a positive effect on outcome.

A number of limitations of this study should be considered when interpreting the results. First, maternal smoking was not available in this study and is one of the most important risk factors related to SGA infants.46 However, previous research among women in this region indicated that the prevalence of cigarette smoking among pregnant women was below 0.2%.47 Therefore, the impact of missing information of cigarette smoking may be limited. Second, we only had maternal BMI measured at GCT, but not maternal prepregnancy BMI, which might more accurately reflect mother's energy stores before pregnancy. Third, participants in this study had only a 1 hour 50 g GCT and not the 75 g OGTT. Thus, we are unable to determine whether women with all these maternal characteristics below the cut-off limits also had high insulin sensitivity. Fourth, all women in this study are Chinese and the majority are Han ethnicity. Thus, the results from this study may not be generalisable to other racial groups. Finally, we have no measure of the mother's energy expenditure or demands and its relationship to nutritional intake before or during pregnancy. Nevertheless, the major strengths of this study are that the women were from a very large prospective cohort, which is well representative of the study population, with important information related to participants' sociodemographic characteristics during their early pregnancy and followed them to delivery.

In conclusion, among women with a normal BG level at GDM screening measured at 24–28 weeks of gestation, low BG is associated with an increased risk of having an SGA infant. The risk of SGA will be further increased when the mother is short and has a low BMI. This may be another useful clinical tool for identifying women with higher risk for SGA infant at delivery and provides an opening for research into prophylactic interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all women and their children who participated in this study and medical staffs in Beichen District who helped in collection of the related information. The authors also thank Drs Shigeru Aoki and Geir W Jacobsen for their reviewing this paper and, specially, Dr Geir W Jacobsen for his valuable comments and editing to improve its quality.

Footnotes

Contributors: GL, JuL and JL conceived and designed the study. JW and HL were involved in the data collection and laboratory processing. JH, XY, JuL and JL framed the research theme, analysed and interpreted the data for this article. JZ and JL initiated statistical analysis and drafted the paper. JH critically revised the manuscript and all authors reviewed the important intellectual content. GL, JuL and JL are the guarantors.

Funding: This research was funded by Brock University Advancement Funds (grant numbers: 336-737-802, 336-737-057).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Brock University and Tianjin Women and Children Health Center.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Alkalay AL, Graham JM Jr, Pomerance JJ. Evaluation of neonates born with intrauterine growth retardation: review and practice guidelines. J Perinatol 1998;18:142–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hawdon JM, Ward Platt MP. Metabolic adaptation in small for gestational age infants. Arch Dis Child 1993;68(3 Spec No):262–8. 10.1136/adc.68.3_Spec_No.262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trudell AS, Cahill AG, Tuuli MG et al. . Risk of stillbirth after 37 weeks in pregnancies complicated by small-for-gestational-age fetuses. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013;208:376.e1–7 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karahasanoğlu O, Karatekin G, Köse R et al. . Hypoglycemia in small-for-gestational-age neonates’. Turk J Pediatr 1997;39:159–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Majnemer A, Rosenblatt B, Riley PS. Influence of gestational age, birth weight, and asphyxia on neonatal neurobehavioral performance. Pediatr Neurol 1993;9:181–6. 10.1016/0887-8994(93)90081-M [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhat MA, Kumar P, Bhansali A et al. . Hypoglycemia in small for gestational age babies. Indian J Pediatr 2000;67:423–7. 10.1007/BF02859459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Figueras F, Eixarch E, Meler E et al. . Small-for-gestational-age fetuses with normal umbilical artery Doppler have suboptimal perinatal and neurodevelopmental outcome. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2008;136:34–8. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2007.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chamberlain G. ABC of antenatal care. Small for gestational age. BMJ 1991;302:1592–6. 10.1136/bmj.302.6792.1592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karlberg J, Albertsson-Wikland K. Growth in full-term small-for-gestational-age infants: from birth to final height. Pediatr Res 1995;38:733–9. 10.1203/00006450-199511000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee PA, Houk CP. Cognitive and psychosocial development concerns in children born small for gestational age. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev 2012;10:209–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lundgren EM, Tuvemo T. Effects of being born small for gestational age on long-term intellectual performance. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;22:477–88. 10.1016/j.beem.2008.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaskins RB, LaGasse LL, Liu J et al. . Small for gestational age and higher birth weight predict childhood obesity in preterm infants. Am J Perinatol 2010;27:721–30. 10.1055/s-0030-1253555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taal HR, Vd Heijden AJ, Steegers EA et al. . Small and large size for gestational age at birth, infant growth, and childhood overweight. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21:1261–8. 10.1002/oby.20116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiavaroli V, Marcovecchio ML, de Giorgis T et al. . Progression of cardio-metabolic risk factors in subjects born small and large for gestational age. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e104278 10.1371/journal.pone.0104278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katz J, Lee AC, Kozuki N et al. . Mortality risk in preterm and small-for-gestational-age infants in low-income and middle-income countries: a pooled country analysis. Lancet 2013;382:417–25. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60993-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCowan L, Horgan RP. Risk factors for small for gestational age infants. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2009;23:779–93. 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2009.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu J, Sempos C. Foetal nutritional status and cardiovascular risk profile among children. Public Health Nutr 2007;10:1067–75. 10.1017/S136898000768389X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siega-Riz AM, Viswanathan M, Moos MK et al. . A systematic review of outcomes of maternal weight gain according to the Institute of Medicine recommendations: birthweight, fetal growth, and postpartum weight retention. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;201:339.e1–14 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lederman SA. Pregnancy weight gain and postpartum loss: avoiding obesity while optimizing the growth and development of the fetus. J Am Med Womens Assoc 2001;56:53–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scholl TO, Sowers M, Chen X et al. . Maternal glucose concentration influences fetal growth, gestation, and pregnancy complications. Am J Epidemiol 2001;154:514–20. 10.1093/aje/154.6.514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim S, Min WK, Chun S et al. . Quantitative risk estimation for large for gestational age using the area under the 100-g oral glucose tolerance test curve. J Clin Lab Anal 2009;23:231–6. 10.1002/jcla.20326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sameshima H, Kamitomo M, Kajiya S et al. . Early glycemic control reduces large-for-gestational-age infants in 250 Japanese gestational diabetes pregnancies. Am J Perinatol 2000;17:371–6. 10.1055/s-2000-13450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pedersen J. The pregnant diabetic and her newborn: problems and management. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bazaes RA, Salazar TE, Pittaluga E et al. . Glucose and lipid metabolism in small for gestational age infants at 48 hours of age. Pediatrics 2003;111(Pt 1):804–9. 10.1542/peds.111.4.804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cianfarani S, Maiorana A, Geremia C et al. . Blood glucose concentrations are reduced in children born small for gestational age (SGA), and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels are increased in SGA with blunted postnatal catch-up growth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:2699–705. 10.1210/jc.2002-021882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bienstock JL, Holcroft CJ, Althaus J. Small fetal abdominal circumference in the second trimester and subsequent low maternal plasma glucose after a glucose challenge test is associated with the delivery of a small-for-gestational age neonate. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2008;31:517–19. 10.1002/uog.5316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Calfee EF, Rust OA, Bofill JA, et al. Maternal hypoglycemia: is it associated with adverse perinatal outcome? J Perinatol 1999;19:379–82. 10.1038/sj.jp.7200048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melamed N, Hiersch L, Peled Y et al. . The association between low 50 g glucose challenge test result and fetal growth restriction. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2013;26:1107–11. 10.3109/14767058.2013.770460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vadakekut ES, McCoy SJ, Payton ME. Association of maternal hypoglycemia with low birth weight and low placental weight: a retrospective investigation. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2011;111:148–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leng JJ, Liu G, Wang J et al. . The association between glucose challenge test level and fetal nutritional status. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2013;27:479–83. 10.3109/14767058.2013.818972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan BC, Lao TT. Maternal height and length of gestation: does this impact on preterm labour in Asian women? Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2009;49:388–92. 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2009.01006.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong W, Tang NL, Lau TK et al. . A new recommendation for maternal weight gain in Chinese women. J Am Diet Assoc 2000;100:791–6. 10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00230-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin WY, Tsai SL, Albu JB et al. . Body mass index and all-cause mortality in a large Chinese cohort. CMAJ 2011;183:8 10.1503/cmaj.101303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Leeuwen M, Louwerse MD, Opmeer BC et al. . Glucose challenge test for detecting gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. BJOG 2012;119:393–401. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03254.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lurie S, Levy R, Weiss R et al. . Low values on 50 gram glucose challenge test or oral 100 gram glucose tolerance test are associated with good perinatal outcome. J Obstet Gynaecol 1998;18:451–4. 10.1080/01443619866778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Economides DL, Nicolaides KH. Blood glucose and oxygen tension levels in small-for-gestational-age fetuses. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1989;160:385–9. 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90453-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cekmez Y, Ozkaya E, Öcal FD et al. . A predictor of small-for-gestational-age infant: oral glucose challenge test. Ir J Med Sci 2015;184:285–9. 10.1007/s11845-014-1101-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abell DA, Beischer NA. Evaluation of the three-hour oral glucose tolerance test in detection of significant hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes 1975;24:874–80. 10.2337/diab.24.10.874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shinohara S, Hirai M, Hirata S et al. . Relation between low 50-g glucose challenge test results and small-for-gestational-age infants. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2015;41:1752–6. 10.1111/jog.12794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lind T, Anderson J. Does random blood glucose sampling outdate testing for glycosuria in the detection of diabetes during pregnancy? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984;289:1569–71. 10.1136/bmj.289.6458.1569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group. Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) Study: associations with neonatal anthropometrics. Diabetes 2009;58:453–9. 10.2337/db08-1112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barbour LA, McCurdy CE, Hernandez TL et al. . Cellular mechanisms for insulin resistance in normal pregnancy and gestational diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007;30(Suppl 2): S112–9. 10.2337/dc07-s202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rogne T, Jacobsen GW. Association between low blood glucose increase during glucose tolerance tests in pregnancy and impaired fetal growth. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2014;93:1160–9. 10.1111/aogs.12365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barker DJ. The malnourished baby and infant. Br Med Bull 2001;60:69–88. 10.1093/bmb/60.1.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu J, Leng J, Tang C et al. . Maternal glucose level and body mass index measured at gestational diabetes mellitus screening and the risk of macrosomia: results from a perinatal cohort study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004538 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitchell EA, Thompson JM, Robinson E et al. . Smoking, nicotine and tar and risk of small for gestational age babies. Acta Paediatr 2002;91:323–8. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2002.tb01723.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang X, Hsu-Hage B, Zhang H et al. . Gestational diabetes mellitus in women of single gravidity in Tianjin City, China. Diabetes Care 2002;25:847–51. 10.2337/diacare.25.5.847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]