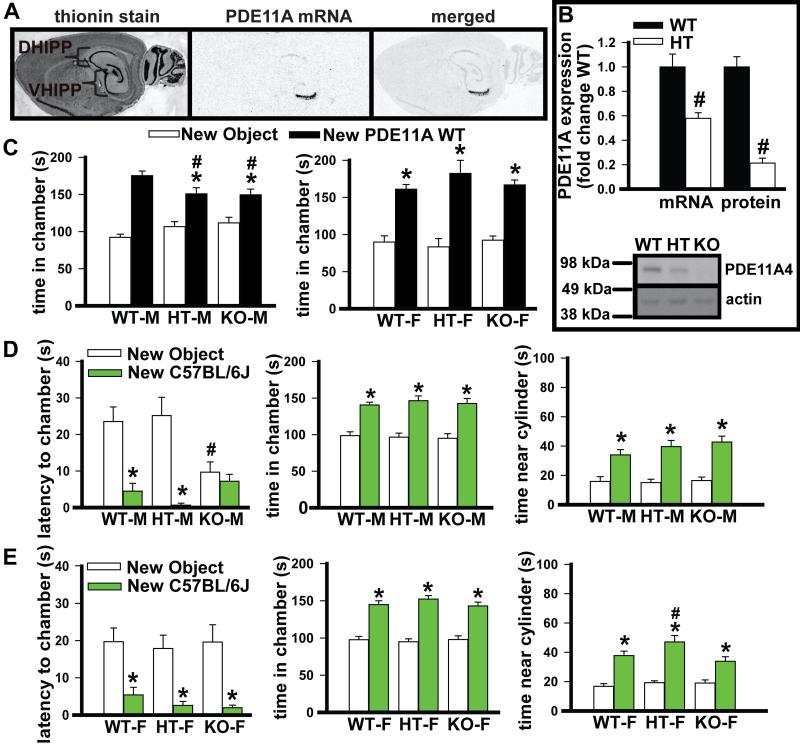

Fig. 1.

PDE11A mRNA expression is restricted to the hippocampal formation and deletion alters social approach in a manner that depends on the strain of the stimulus mouse. (A) As previously reported (Kelly et al., 2010, 2014; Kelly, 2014, 2015), PDE11A mRNA is selectively expressed in CA1 (and possibly ventral CA2), subiculum, and the adjacent amygdalohippocampal area (not shown at this level), with a 3- to 10-fold enrichment in ventral (VHIPP) versus dorsal hippocampus (DHIPP). (B) As expected, PDE11A heterozygous (HT; n = 6 (3 females)) mice show a 50% reduction in ventral hippocampal (VHIPP) PDE11A mRNA expression relative to wild-type (WT) littermates (n = 7 (4 females)), as measured by Q-PCR (t(11) = 3.47, P = 0.005). Note, no signal was detected in samples from PDE11A knockout (KO) mice, proving specificity of the primer/probe sets (data not shown). Surprisingly, however, PDE11A HT mice (n = 9 (5 females)) show an 80% reduction in VHIPP PDE11A4 protein expression relative to WT littermates (n = 10 (5 females)), as measured by Western blot (t(17) = 8.20, P < 0.001; shown in lower panel). Identical results were obtained in dorsal hippocampal samples from these mice as well as whole hippocampus samples from a second cohort of mice (data not shown). The mechanism underlying this disconnect between mRNA and protein remains to be determined, but alterations in social behavior driven by the HT deletion may further drive down PDE11A4 protein expression in the PDE11A HT mice (e.g., see Fig. 5A). (C) (Left) When given a chance to explore a novel object vs. a novel PDE11A WT mouse, adult male PDE11A mutant mice (i.e., HT, n = 8, and KO mice, n = 10) exhibited reduced social approach relative to that of male WT littermates (n = 14; F(2,26) = 4.50, P = 0.021). (Right) in contrast, female PDE11A WT (n = 7), HT (n = 3), and KO mice (n = 9) spent equivalent amounts of time with a novel mouse from the PDE11A colony (F(1,16) = 68.77, P < 0.001). This sex-specific phenotype in group-housed mice bred onsite is consistent with our previous report in single-housed mice bred offsite (Kelly et al., 2010). Note: latency to chamber and time near the cylinder were not available for this experiment. (D) Changing the stimulus mouse to a C57BL/6J altered the pattern of behavior seen in PDE11A mutant mice. (Left) male PDE11A KO mice (n = 18) failed to show a significant social preference in terms of their latency to approach the new C57BL/6J mouse vs. the new object, having approached the novel object much more quickly than their male HT (n = 14) and WT littermates (n = 20; effect replicated in 2 cohorts of mice, combined analysis: F(2,49) = 4.82, P = 0.012). (Middle) despite this difference in latency to approach, PDE11A KO males exhibited significant social preference in terms of their time in each chamber (F(1,49) = 55.22, P < 0.001) and (right) time near each cylinder (F(1,49) = 54.60, P < 0.001). (E) Unlike PDE11A KO males, (left) PDE11A KO females (n = 17) showed a significance preference for the new C57BL/6J mouse vs. the new object, as did PDE11A WT and HT females (WT, n = 27; HT, n = 22), in terms of their (left) latency to approach (F(1,63) = 31.78, P < 0.001) as well as their (middle) time in chamber (F(1,63) = 87.15, P < 0.001), and (right) time near the cylinder (F(2,57) = 4.57, P = 0.014), with PDE11A HT females showing significantly greater social approach on the last measure. Post hoc, *vs. object, P < 0.001; #vs. WT, P < 0.05–0.001.