Abstract

We propose an improved version of variable-angle total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (vaTIRFM) adapted to modern TIRF setup. This technique involves the recording of a stack of TIRF images, by gradually increasing the incident angle of the light beam on the sample. A comprehensive theory was developed to extract the membrane/substrate separation distance from fluorescently labeled cell membranes. A straightforward image processing was then established to compute the topography of cells with a nanometric axial resolution, typically 10–20 nm. To highlight the new opportunities offered by vaTIRFM to quantify adhesion process of motile cells, adhesion of MDA-MB-231 cancer cells on glass substrate coated with fibronectin was examined.

Introduction

Adhesion and migration are essential to normal and pathological cellular activities. During these processes, cells interact with each other and with their environment through a broad range of specific and nonspecific interactions. The specific cell binding is regulated by lock-and-key mechanisms, related to the presence of protein receptors (such as integrins or cadherins) at the cell surface, which can recognize specifically ligands located on other cells or in the extracellular environment (1). Cell adhesion also results from the synergy between various long- and short-range cell-substrate nonspecific interactions, mediated, for example, by van der Waals forces, electrostatic forces, polymer steric repulsive forces, or thermal induced undulation forces (2). To add further to the complexity, all the molecules involved in cell adhesion processes can move in accordance with the fluidity of the plasma membrane, the dynamical reorganization of the cytoskeleton, and the global elasticity of the cell envelope. Such dynamic aspect of the adhesion process is crucial and remains largely unknown. Hence, cell adhesion is a highly dynamic and multiparameter phenomenon, which can be addressed in different ways; for example, by combining optical microscopy either with micropipette manipulation of cells (3), or by using fluid microjet to induce shear force on cells (4), or simply by atomic force microscopy (5).

Specific adhesion can be studied with the usual fluorescence techniques, such as that of confocal fluorescence microscopy (6), or a more resolved technique, such as interferometric photoactivated localization microscopy (PALM) (7), by labeling the proteins involved in the adhesive structures, the so-called focal adhesion complexes. Standard total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy is also well suited to observe focal adhesion zones (8). On the other hand, nonspecific interactions can be assessed by measuring distances from the substrate to the plasma membrane, because forces that govern nonspecific adhesions are distance-dependent. As live cell adhesion remains a complex issue, nonspecific interactions have been preferentially studied on biomimetic systems such as giant unilamellar vesicles with reflection interference contrast microscopy (RICM) (9). RICM is a very interesting technique because it does not require a complex optical setup and provides distance measurements with a nanometric resolution on micrometric beads or on giant unilamellar vesicles. Unfortunately, RICM cannot be applied optimally on living cells to precisely determine membrane/substrate separation distances, mainly because RICM image processing needs a perfect knowledge of the cytoplasmic refractive index (9). At the single cell level this index is very inhomogeneous and changes drastically in time and in space, due to the presence of numerous intracellular organelles and protein assemblies such as stress fibers.

Some recent publications demonstrate that specific and nonspecific forces involved in cellular adhesion appear to have a cooperative action, as regards the influence of glycocalyx on integrins. The nonspecific forces induced by the glycocalyx are mostly ensured by the presence of glycoproteins, which expose at the cell surface a wide range of long, short, and branched chains of negatively charged oligosaccharides. Paszek et al. (10) highlighted that the glycocalyx can alter the integrin-based focal adhesion plaques and promote migration of tumor cells. The expected impact of the glycocalyx on adhesion has been also emphasized on biomimetic systems, where it is supposed to exert a nonspecific steric repulsive force (11, 12). As a result, we propose a real-time imaging technique to probe simultaneously the specific and the nonspecific aspects of adhesion process. This technique, called variable-angle total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (vaTIRFM), allows us to map the membrane-substrate separation distance with a nanometric resolution at typical acquisition rate of 1 s. Compared to other techniques of imaging that also provide a nanometric axial resolution, vaTIRFM presents two main advantages: it is compatible with usual techniques of cell observation, and it does not induce photodamage to the specimen.

First, cells are placed on a common glass coverslip, which can be easily coated with various proteins such as collagen or fibronectin to promote specific adhesion. This permits conventional bright-field observations with phase contrast, differential interference contrast, or interferometric techniques such as RICM; these are very useful to check the morphology and the general health of cells. This deserves to be highlighted as, among all new techniques allowing nanoscale localization along the optical axis, some of them use nontransparent or semitransparent substrates. Consequently, regular bright-field imaging techniques either cannot be used properly or cannot be used at all. This is especially the case of scanning angle interference microscopy, which uses a reflective silicon substrate (13). In the same way, some other recent techniques propose to exploit the well-established modification of the fluorescence lifetime near plasmonic substrates, such as nanostructured metallic thin films (14), or just a thin metallic film (15). Moreover, concerning the sample preparation, the coating of metallic film or nanoparticles with proteins to probe specific interactions significantly increases the level of complexity of the system.

The second advantage concerned the photodamage of cells and their preparation, which is a crucial issue for any relevant investigations about adhesion. The technique proposed in this article is not based on single molecule detection. Consequently, it enables observation at a sampling rate on the order of 1 s together with a very low laser irradiance (typically ∼10 W/cm2). The corresponding surface density of energy (∼10 J/cm2) is significantly smaller than the usual light dose used in common superresolution techniques, typically at least 102–103 kJ/cm2 in single-molecule localization microscopy techniques, such as interferometric PALM (7) and stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM) combined with supercritical-angle analysis (16, 17, 18), or ∼104 kJ/cm2 in stimulated emission depletion microscopy (19). Surface density of energy employed in vaTIRFM is also notably smaller than the lethal dose of irradiation recently measured on living cells, typically a few hundreds of kJ/cm2 (20). It should be noted that the irradiation dose used in most of the superresolution microscopy experiments (PALM, STORM, stimulated emission depletion, etc.) is much higher than this lethal dose, which means that these techniques lead to an important photodamage of cells during the exposure time. Furthermore, to quantify the adhesion of living cells we propose to measure membrane-substrate distances. This can be achieved with a simple plasma membrane labeling using an amphiphilic dye molecule. Specific adhesion zones would be observed when the plasma membrane most closely approaches the substrate, as highlighted many times in the literature (7, 13, 21, 22). Thus, cell preparation is less restrictive, because no particular labeling of adhesion proteins is required in our experiments. Furthermore, the cells remain alive and do not need to be fixed. So with our approach we favor real-time nondestructive observations, where cells can freely migrate above the substrate. In these conditions, it is possible to study the dynamic aspects of the adhesion process.

Last but not least, the axial range of measurement with vaTIRFM is ∼300–400 nm above the substrate. This point is crucial to observe nonspecific interactions that can induce forces high enough to repel the cell far from the substrate (>100 nm). It is therefore important to note that most of the fluorescence techniques previously cited have an axial working range limited to 100–150 nm. To conclude on benefits of vaTIRFM, this approach can be easily implemented on any TIRF microscope, as the experimental setup offers a fine control of the light beam incident angle.

The evanescent wave created at the glass-medium interface by total internal reflection is characterized by an exponential decay of the electric field with the distance z from the interface (23). The penetration depth of the evanescent wave is typically a few hundred nanometers. Thereby, only the dye molecules close to the interface will be excited. Consequently in TIRFM, only a small thickness of the ventral part of the cell body will be illuminated, as illustrated in Fig. 1. This point is important for long time observations of motile cells, because evanescent excitation limits significantly the photodamage of all the specimen. In fact, this is one of the reasons why, nowadays, TIRFM is widely used by biologists to observe focal adhesion zones and localize those specific events in the (x,y)-plane in regards to the cell morphology (8). As we previously explained, quantitative interpretation of TIRF picture regarding the distance between a stained membrane and the substrate (Fig. 1) is not trivial (24). Indeed, the contrast of TIRF images depends on several parameters more or less well known, such as the local concentration of dyes, their orientation, and consequences on their absorption cross section and angular emission pattern (25). The strategy to get around this problem is to exploit a series of TIRF pictures recorded at different incident angles in evanescent regime, as proposed in vaTIRFM. This technique was introduced for the first time by Lanni et al. (21) and Gingell et al. (26) in 1985. In the middle of the 1990s, two noteworthy studies proposed, for the first time a quantification of the membrane/substrate distance on focal adhesion zones (22), and a map of these distances providing the topography of cells above a substrate (27). More recently, vaTIRFM was used to measure the axial motion of secretory-granule in the ventral side of living cells (28) and to reveal the influence of 5-aminolevulinic acid on the adhesion of tumor cells (29). The shared characteristic of all these vaTIRFM experiments, which also constitutes their major drawback, is that a prism is employed to produce the evanescent wave. The microscope objective is then automatically mounted at the opposite side of the sample to collect the signal, and the fluorescence image of the ventral membrane is obtained through the cell body. By this method, however, the image quality is not good enough to observe the plasma membrane in detail. To address this issue, a prismless approach in TIRFM has been proposed (30). Indeed, a prismless setup based on an inverted microscope equipped with a high numerical aperture (NA) objective (NA > 1.4), gives pictures with the full resolution defined by the NA. In this configuration, the objective was used to create the evanescent excitation and to collect the signal. With the prismless setup, it is also much easier to install and develop optical systems to tune the light beam incident angle. Boulanger et al. (31) demonstrates the great capability provided by a prismless setup employed in vaTIRFM to image, with a high resolution, the cortical actin network.

Figure 1.

Schematic drawing of an adherent cell spreads on a glass substrate illuminated by evanescent waves (the incident angle θ is greater than the critical angle θv). (Inset) The plasma membrane is labeled with DiO molecules. The value is the distance from the substrate to the membrane. To see this figure in color, go online.

We propose in this article an updated version of vaTIRFM, including a convenient prismless setup and an improvement of data processing of TIRF images. Our custom microscope only uses a rotatable mirror to precisely and quickly adjust the focused laser beam on the back focal plane (BFP) of the objective. No azimuthal scanning of the laser beam in the BFP (as it is performed in Boulanger et al. (31)) is needed with our setup, which is a great advantage regarding data acquisition. Moreover, we have developed a complete theory based on the scalar treatment of incoherent image formation, to take into account the parameters that influence the contrast of TIRF images. Furthermore, an original data processing is proposed to eliminate all the unknown parameters previously mentioned, thus allowing us to extract easily the membrane/substrate separation distance from fluorescently labeled cell membranes. As a result, a series of TIRF images recorded at different incident angles enables us to calculate over the entire ventral part of the cell, thus allowing us to reconstruct the cell topography with a nanometric accuracy. Finally, we will highlight the benefits of vaTIRFM to investigate cellular adhesion in the case of MDA-MB-231 motile cells, in adhesion on glass substrate coated with a thin layer of fibronectin, a well-known protein that gives rise to specific adhesion.

Materials and Methods

Microscope

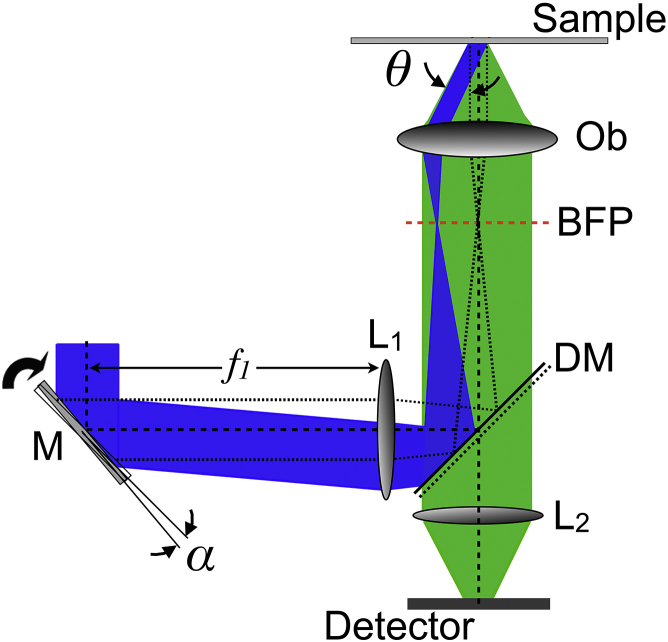

To accurately control the incident angle of the laser beam, we developed our own setup (see Fig. 2; a more detailed optical setup is given in Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material). The most significant part of the setup is a mirror (M, Fig. 2) mounted onto a motorized rotation stage outside the microscope. It allows us to adjust the incident angle θ at the glass-water interface by tilting the mirror by an angle α. The working range is from 0° (epi-illumination mode) to the maximum angle θ ≈ 72° given by the numerical aperture of the objective (PlanApoN 60×, NA = 1.45; Olympus, Melville, NY). The calibration procedure required to establish the magnification relationship between α and θ is detailed in a previous publication (32). The angle α can be continuously tuned with an accuracy of ±1 × 10−4 degrees (PRS-110; PI Micos, Eschbach, Germany). In epi-fluorescence, the laser beam at 488 nm (Sapphire 488–200 mW; Coherent, Santa Clara, CA) is redirected onto the sample with a dichroic mirror (DM) and focused with an appropriate lens (L1) on the center of the BFP of the objective. The illumination area of the sample is very large, allowing us to simultaneously observe several cells. The lateral waist of the excitation profile is ∼120 μm (see Fig. S2 for more details). To avoid a maximum of aberrations, the rotatable mirror M needs to be placed exactly on the rear focal plane of L1. In this manner, lateral displacement and any distortion of the illumination zone when the incident angle is increased, are suppressed (see Figs. S3 and S4; no azimuthal scanning of the focused laser beam in the BFP is required with our experimental setup because the illumination field is uniform in TIRFM; no local interference was observed). In TIRF configuration, the laser beam is focused at the periphery of the pupil entrance of the objective and it next propagates along the edge of the objective aperture. The fluorescence signal from the sample is then collected by the same objective and imaged onto a CMOS camera (ORCA Flash 4.0; Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu City, Japan). A fine achievement of the axial focusing is provided by a z-piezo device supporting the objective (Physik Instrumente, Auburn, MA). To conclude, the microscope is enclosed in a hermetic chamber to make observation at 37°C.

Figure 2.

Experimental setup. The excitation beam is in blue and the fluorescence signal is in green. (M, rotatable mirror; L1, focusing lens (with the focal length f1); DM, dichroic mirror; Ob, microscope objective; BFP, back focal plane of the objective; L2, tube lens.) To see this figure in color, go online.

In all experiments, the polarization of the incident laser beam was fixed in s configuration (TE). Then, the polarization state in TIRF is also in s configuration. As a result, the molecules that have a transition dipole moment parallel to the interface will be efficiently excited.

Glass surface functionalization

Specific and nonspecific adhesion processes can be tested on a solid substrate such as a glass coverslip functionalized with various biomolecules. To observe specific adhesion, we prepared glass surfaces coated with a thin layer of fibronectin. Fibronectin is one of the most widespread extracellular matrix components used in cell adhesion investigation. Indeed, cells would easily develop binding with fibronectin through receptors present on their membrane, such as integrins α3β1, α5β1, α8β1, αvβ1, αvβ3, etc. (33).

The challenge of this surface functionalization is to precisely control the thickness of the fibronectin layer. The first step is to clean and activate the coverslips by immersion into freshly prepared piranha solution for at least 30 min (50% H2O2 and 50% H2SO4). The coverslips are then rinsed with ultra-pure water and dried with argon gas. In this manner, the glass surfaces will be negatively charged due to the presence of silanol groups (SiOH-terminated). The second step is to incubate the cleaned coverslips in a solution of fibronectin (fibronectin from human plasma at 0.1%, F0895; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) diluted in phosphate buffer solution at 10 μg/mL (phosphate buffer solution at pH = 7.2) during 1 h. Fibronectin proteins are physisorbed as a result of electrostatic interactions between silanol and their amine groups. Finally, to remove the nonabsorbed fibronectin on SiOH surfaces, coverslips were rinsed with ultra-pure water and dried with argon gas.

The fibronectin-coated coverslips were then characterized with contact angle measurement to ensure the homogeneity of the layer. Water contact angles were measured under ambient atmosphere at room temperature by using the sessile drop method and an image analysis of the drop profile (OCA15EC system; Data Physics, San Jose, CA). As expected, SiOH surfaces are hydrophilic, with a contact angle <5°. After deposition of fibronectin the coverslips became hydrophobic, with a contact angle of (49 ± 2)° measured over several coverslips. The layer thickness was estimated by ellipsometry on a silicon wafer, according to the same surface functionalization (UVISEL; Horiba Jobin-Yvon, Edison, NJ). We obtained a mean fibronectin thickness of 4 ± 1 nm.

Cell culture and sample preparation

MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells were grown in Minimum Essential Medium (MEM Glutamax-I; Gibco/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) supplemented with 10% of fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco) and 1% of antibiotics (penicillin 100 U/mL and streptomycin 100 μg/mL; Gibco) in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C with 5% CO2. For vaTIRF observations, cells were placed in a chamber that contains a nonfluorescent culture medium at 488 nm. We used DMEMgfp-2 medium (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium; Evrogen, Moscow, Russia), which includes no phenol red, no riboflavin, and only a low amount of folic acid. DMEMgfp-2 was then supplemented with L-glutamine at 2 mM (Gibco), HEPES buffer at 10 mM (N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N-2-ethane sulfonic acid, Gibco), and just 1% of FBS.

For plasma membrane labeling, we used well-known DiO probe (3,3′-dioctadecyloxacarbocyanine perchlorate, DiOC18(3), Cat. No. D275; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). We employed DiO because their absorption transition moment is roughly parallel to the membrane (34). Consequently such amphiphilic dye will be efficiently excited with s-polarized light. To stain the plasma membrane with DiO, ∼3.105 cells were suspended (using trypsin) in 1 mL of the nonfluorescent culture medium. Next, 7 μL of a solution of DiO diluted in DMF at 700 μM was gently mixed with cells and incubated for 10 min at 37°C with 5% of CO2 (the final concentration of DiO is ∼5 μM). To remove the DiO molecules not internalized, labeled cells were washed three times by centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 5 min, by changing the nonfluorescent medium and resuspending the cells in warm medium between each spin. After the final spin, the MDA-MB-231 cells were placed into a cylindrical homemade hermetic chamber (to avoid evaporation) made with two coverslips and dedicated to optical observations. The lower coverslip was previously coated with fibronectin. To promote the adhesion of cells, this sample was incubated for 1 h at 37°C in the presence of 5% of CO2. Next, the observations were done during the first 30 min after incubation.

Theoretical description

Fluorescence signal in TIRFM

A theoretical description of vaTIRFM can be proposed assuming some approximations. One can firstly suppose that only the plasma membrane of cells anchored to the substrate will be excited by the evanescent wave. This approximation is reasonable as long as the penetration depth of the evanescent wave is still smaller than the cell thickness. Note that this approximation is not valid at the periphery of the cell (this point will be discussed later). Next, one also assumes that the membrane is very thin compared to the wavelength, and locally flat at the -scale, as illustrated in Fig. 1. As we proposed in a previous publication (24), the fluorescence signal (after background subtraction) recorded in wide-field fluorescence microscopy, at the pixel of the camera used in our experiment, can be written as follows:

| (1) |

where is the detection point-spread function for a pixel of the camera; and is the fluorescence signal emitted at the position within the sample, which can be written as

| (2) |

where is the detection efficiency; and and are, respectively, the absorption cross section and the quantum yield of the dye molecules used. If the fluorescent molecules are located close to a dielectric interface, all these parameters will strongly depend on the distance from the interface to the molecules (25). is the light excitation profile within the sample; is the energy of a photon; and C represents the local distribution of dyes within the sample.

For a simple interface between two dielectric media, such as glass-water interface, the squared modulus of the evanescent electric field that appears under TIR condition, , decays exponentially with the perpendicular distance z from the interface (23). The parameter that characterizes this exponential decay, denoted κ and called “attenuation length”, depends on the laser excitation wavelength, the incident angle of the laser beam, and the refractive indices of the two media situated on both sides of the interface. Unfortunately, the presence of a cell in adhesion on the glass substrate can affect this evanescent field. Consequently, TIRF experiments on living cells require the consideration of a stratified multilayer system to accurately describe the evanescent field within the sample. In the context of TIRF microscopy, several previous publications have already addressed such multilayer systems (35, 36). As a result, to evaluate the evanescent electric field intensity that contributes to the fluorescence signal emitted by dyes located in the plasma membrane, only a three-layer stack of different media needs to be considered, as illustrated in Fig. 3 A (the plasma membrane can be neglected, as it is very thin). The first layer is the glass substrate of refractive index ng, the second is the aqueous medium for cell observation of refractive index nmed, and the third layer is the cytoplasm of refractive index . At 488 nm, ng = 1.53 and nmed = 1.336. Regarding , one can find in the literature typical values comprised between 1.36 and 1.39, whatever the cell line (37, 38, 39). According to Gingell et al. (35), the exact expression of the squared modulus of the evanescent electric field for a three-layer system (in s-polarized light) can be used to plot the decay of the evanescent wave in the medium intermediate layer between the cell and the substrate, as shown in Fig. 3 B (circle dots). These calculated values of the evanescent field intensity appear to fit very well a single exponential decay expected for a simple interface, i.e., , where the attenuation length κ involves an effective refractive index of the sample, which includes the combined influence of the water gap thickness and cytoplasmic refractive index on the evanescent wave:

| (3) |

Figure 3.

(A) The three-layer dielectric model used to calculate the evanescent electric field intensity in the interspace between the cell and the glass substrate. (B, circle dots) calculation for s-polarized light, plotted as a function of the axial distance , for = 100 nm, = 1.37. (B, solid line) Fit according to a single exponential decay (, where κ is given by Eq. 3). (C) Evolution of the effective refractive index as a function of the medium gap thickness , plotted for different values of . For all the simulations, θ = 65°, = 488 nm, = 1.53, and = 1.336.

It is then possible to determine the value of , for a specific water gap thickness and a value of . For example, we obtained 1.3605 from data shown in Fig. 3 B. Thus, we have plotted the variation of versus , according to different values of , in Fig. 3 C. Hence, the light excitation will also depend on through the expression of κ. Finally, can be written in TIRF as the following:

| (4) |

where is the lateral waist of the excitation profile, and is the laser irradiance at . The value γ is the correction factor, which takes into account the variation of the electric field intensity at the glass/water interface with the incidence angle (23). The value γ is defined to be equal to unity at θ = 0, and, for s-polarized light, is given by

| (5) |

with .

By replacing the membrane with a uniform thin fluorescent plane, , where is the local mean number of dye molecules, and δ is the Dirac function. By combining Eqs. 1, 2, and 4, the corresponding fluorescence signal recorded on one pixel of the camera will be:

| (6) |

Variable-angle TIRFM

As previously explained in the introduction, the fluorescence signal in TIRF is z-dependent through several parameters. The value is not only governed by the exponential decay of the evanescent wave. It is particularly affected by unknown parameters such as the point spread function, the local concentration of dyes, and their orientations, which play on the absorption cross section, the detection efficiency, and the quantum yield. Moreover, these three last parameters can be strongly altered as a function of when (25). But interestingly, all these mentioned parameters do not depend on θ for s-polarized light. In other words, their values will not change by varying the incident angle, as it is intended to accomplish in vaTIRFM. So, one can propose to include all these unknown parameters in a new factor, denoted χ:

| (7) |

VaTIRFM takes advantage of dependence of the attenuation length κ on the incident angle θ (Eq. 3). By gradually increasing the incident angle, a series of TIRF images (for example, 10 images) for different attenuation lengths is recorded. As we will demonstrate, these stacks of images are then used to calculate the separating distance between the fluorescent plane and the interface. The fluorescence signals recorded at the pixel of the camera, for different incident angle ( the critical angle), with and , are:

| (8) |

Taking the natural logarithm of the expressions in Eq. 8 after easy rearrangement yields the following new expressions:

| (9) |

Therefore, increases linearly with respect to , with a slope of and a y axis intercept of . So, by processing to a linear fit in each pixel of the camera, one can obtain the membrane/substrate separation distance, without requiring any information on parameters related to the molecular orientation and the local concentration of dyes . Note that is interestingly equal to for s-polarized light (Eq. 5). As a result, this irradiance correction factor will not depend on the refractive indices and , and only κ will rely on and (see Eq. 3).

Results and Discussion

As experimentally and theoretically demonstrated by Burmeister et al. (22), the fluorescence contribution of the dorsal part of the cell membrane in TIRF can be neglected if the incident angle θ is greater than a threshold value . This approximation is still true at the periphery of cell, such as on pseudopods where the cytoplasmic thickness is very low (typically 0.5–1 μm). , where is the local mean effective refractive index. The value can be easily obtained by plotting the evolution of the mean fluorescence signal as a function of θ, because decreases slowly according to Eq. 6 when (see Fig. S5 for more details). After measurements on numerous MDA-MB-231 cells in adhesion on fibronectin, we have chosen 63.6° as the lowest value of the incident angle suitable for collecting TIRF images. So, for , only the fluorescence signal emitted from the ventral side of the cell membrane is collected. Consequently, the fluorescence signal recorded at the pixel of the camera is given by Eq. 6. Furthermore, even if the theoretical maximum angle achievable with our oil objective is ≈72°, significant defects were observed on TIRF pictures obtained for 68°. This is the main reason why we have decided to stop the vaTIRF measurements at 67.5°.

In Eq. 9, the fluorescence signal is normalized by the irradiance correction factor . This factor takes into account the variation of the laser intensity at the glass/medium interface according to the incidence angle. As previously explained for s-polarized light, this correction factor is equal to . Thus, it does not depend on any refractive indices. In other words, factors can be obtained experimentally on a simple interface, which separates two homogeneous media such as glass/water interface. This requires us to observe the signal emitted by a monolayer of randomly oriented fluorescent species fixed on the interface, as previously proposed in the literature (24, 32). This kind of sample can be obtained by spincoating on the glass coverslip a thin PMMA film doped with quantum dots (QDs). The value was obtained just by measuring the photoluminescence of the QD layer, because the QDs were excited with a very low laser power (far from any saturation process). After 10 repeated measurements at different incident angles, we calculated the mean values of with the error , provided by the standard deviation. As expected, the mean experimental values of the irradiance correction factors are similar to the theoretical ones (see Fig. S6).

All the results presented in this section were obtained for an s-polarized incident light beam. The (x,y)-profile of the laser illumination was large enough to fill the CMOS detector used in our experiment (Fig. S2). The waist of this Gaussian (x,y)-profile was measured to be ∼120 μm (Eq. 4). The laser irradiance in epi-fluorescence, i.e., for 0, was fixed to 5 W/cm2. Hence the light irradiation in TIRFM was typically 10–20 W/cm2, because γ is typically comprised between 2.2 and 3.6 in our experiment. To limit cell exposure, and so the photodamage of the specimen, each TIRF image was typically recorded in 25 or 100 ms. With such laser irradiance and at this acquisition rate, dye photobleaching does not affect the data analysis, as this process only becomes visible after a few seconds of continuous excitation (see Fig. S7). vaTIRFM is based on the recording of a series of several TIRF images on the same area of the sample, by gradually increasing the incident angle θ. As we will demonstrate in this section, only 10 different TIRF images are needed. The incident angle θ was then incremented by 0.4°, starting from 63.6 to 67.2°. Using this method, the total acquisition time for one vaTIRF run is typically in the range of ∼250 ms to ∼1 s (the rotational speed of the mirror is very fast, only a few milliseconds for each step of 0.4°).

Fig. 4 A shows a typical vaTIRF acquisition obtained for a MDA-MB-231 cell in adhesion on a coverslip coated with a thin layer of fibronectin. Increasing the incident angle θ has a major effect on the TIRF images. The fluorescence signal in each pixel diminishes together with the laser irradiance on the glass/medium interface, as predicted by Eq. 6, demonstrating the relevance of the normalization procedure according to the irradiance correction factor . Before data processing, the background signal has to be subtracted to the raw data. Therefore, mean background images were obtained for the same laser power and the same incident angles after taking the cells out of the field of view. The first source of the background signal is the dark noise of the CMOS camera, which is ∼100 counts per pixel, whatever the acquisition time. Next, an additional nonconstant background will appear for acquisition time higher than a few milliseconds. This second one is related to the Raman scattering of water and glass substrate, and more significantly, to the autofluorescence of FBS. This second source of background depends on the laser (x,y)-profile and θ, and it is typically comprised between 50 and 120 counts per pixel for an acquisition time of 100 ms. On the contrary, the fluorescence signal recorded in TIRF on living cells is significantly more important, typically a few thousand counts per pixel (of course this value may change from one cell to another). Although the signal/noise is quite good in our experiment, background subtraction is crucial in data processing.

Figure 4.

(A) vaTIRFM images of the same cell (scale bar = 20 μm.). The incident angles are indicated on the images and the acquisition rate of each TIRF image was 100 ms. (B and C) Data processing on the pixel ( 267, 171) of the vaTIRFM images presented in (A). These data were fitted according to Eq. 10 for plot (B) and Eq. 11 for plot (C). After the fitting procedure, we obtained and nm from data plotted in (B), and nm from data plotted in (C).

Assuming that the detected fluorescence signal is related to DiO molecules located in the ventral part of the cell membrane, as illustrated in Fig. 1, the membrane/substrate distance can be calculated as theoretically proposed. Image processing and analysis routines were developed with IGOR Pro (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR). First, the background is subtracted on all vaTIRFM images. Next, is determined pixel by pixel, according to a dual signal thresholding defined on the first image of the series (i.e., for ). The first threshold corresponds to , allowing us thereafter to evaluate only on the contact region of cell, because it is not relevant to calculate outside the cell. The second threshold permits us to remove the few bright spots appearing on vaTIRFM images, such as those that arise in the center of the cell in Fig. 4 A, which may produce some artifacts. It corresponds to . Even though our cell labeling method is optimal, it is quite normal to observe bright spots related to a probable local bending of the membrane appearing during endocytosis or a membrane budding during exocytosis process, or just dye aggregation. Hence, when , is firstly plotted with respect to (Fig. 4 B). According to the theory proposed in the previous section, these data were then fitted with the following function:

| (10) |

where . Thus one can extract the values of and in each pixel of the image, as in the example shown in Fig. 4 B. Nevertheless, as this fitting procedure includes three free-parameters (Ω, , and ), it is not possible to determine all these parameters with a high accuracy. Investigations on many different cells have revealed that the distance cannot be assessed with a good precision, whereas the accuracy of is excellent. So, to improve the precision on , denoted , we have implemented a second fitting procedure by fixing to its value just obtained. Therefore the second fitting function will be:

| (11) |

The slope of with respect to yields the membrane/substrate separation distance with an optimal accuracy (Fig. 4 C). After this second fit, the values are slightly modified; only the accuracy is improved, as highlighted in Fig. S8. Finally, by this way, i.e., two successive fits in each pixel where , one can obtain the distance from the interface to the membrane over the whole contact area, as represented in Fig. 5 A. This reconstructed image represents the cell surface topography above the glass coverslip coated with fibronectin. As given in Fig. 4, B and C, a weighted fit of the data was performed according to the least-squares method. The absolute error of is simply the sum of the relative error of the irradiance correction factor and the relative error of the fluorescence signal . Instead of a repetitive measurement at the same incident angle, we propose an alternative way to evaluate . In fact, a diffraction-limited spot is typically included in at least a (3×3) pixels square (the actual size of one pixel is ∼0.11 μm). This implies that the fluorescence signal between two adjacent pixels must be relatively close due to the diffraction. Hence can be roughly obtained by calculating the mean absolute difference value between the fluorescence signal in pixel and its eight nearest neighbors , , , , etc.

Figure 5.

Data processing of the vaTIRFM images presented in Fig. 4: image (A) and the corresponding distance histogram (B), image (C), and the error histogram (D), image (E). From image (A), one can calculate the mean membrane/substrate distance = 143 nm and the standard deviation = 35 nm. From image (C), one can also calculate the mean error = 13 nm and the standard deviation = 8 nm. Scale bar = 20 μm. (A) The red arrow indicates the direction of migration. To see this figure in color, go online.

Fig. 5 shows maps of -distances and , which correspond to the vaTIRFM measurements presented in Fig. 4. A map of the error is also plotted, as well as the histograms of the and values. To present a different case of cell adhesion, an additional example of vaTIRFM investigation recorded on another cell is presented in Fig. 6. One can recognize in Figs. 5 and 6 the typical morphology of motile cells, characterized by a teardrop shape and a large membrane protrusion (called the lamellipodium) appearing at the cell front. Such morphology is usually observed on surfaces coated with extracellular matrix proteins, such as collagen or fibronectin, or other substrates that promote cell migration (1, 6). The direction of migration, as well as the front and the rear of the cell, are indicated in Figs. 5 A and 6 B.

Figure 6.

(A) TIRFM image for = 63.6° (acquisition rate = 100 ms). (B–F) Data processing of the vaTIRFM images: image (B) and the corresponding distance histogram (C), image (D), image (E), and the corresponding histogram (F). From image (B), the mean membrane/substrate distance is = 120 nm and the standard deviation is = 42 nm. From image (E), the mean error is = 13 nm and the standard deviation is = 5 nm. Scale bar = 20 μm. (B) The red arrow indicates the direction of migration. To see this figure in color, go online.

Cell surface topography appears on Figs. 5 A and 6 B. As expected, cells do not make a flat contact on a glass substrate coated with fibronectin, but display numerous discrete close contacts that appear primarily at the front and the rear of the cells (see the dark blue regions that correspond to 50 nm). Moreover, the histograms of distances (Figs. 5 B and 6 C), clearly reveal that most of the cell membrane is located between 100 and 200 nm, as previously reported in Lassalle et al. (29). Many different types of information can be extracted from images. The first interesting parameter is the mean distance that separates the cell membrane from the substrate, denoted . We studied 10 different MDA-MB-231 cells on fibronectin, and we obtained an averaged mean value = 137 nm, according to a standard deviation between each cell = 13 nm, which means that membrane/substrate distances will not change drastically between cells. More interestingly, one can also proceed to local measurements on the tight adhesion zones, such as those numbered in Figs. 5 A and 6 B. The characteristics of these close contacts are given in Table 1. We measured a mean membrane/substrate distance comprised between 30 and 45 nm in these regions. It should be noted that the effective refractive index is also the highest on these tight adhesion areas (typically ∼1.37) (Figs. 5 E and 6 D). This implies that the local cytoplasmic refractive index in these regions is slightly higher than 1.37, as indicated by Fig. 3 C. As a result, these close adhesion zones pointed out in Figs. 5 A and 6 B are probably specific adhesion zones, namely old and nascent focal adhesion zones mediated by integrins. The first reason that might validate this claim is the close proximity of the cell membrane above the substrate. Indeed, previous experimental studies have revealed that the typical membrane/substrate distance on focal adhesion regions is typically 25–50 nm (7, 22). The second reason is that MDA-MB-231 cells exhibit receptors ( and integrins) that specifically recognize fibronectin (40, 41, 42). Thereby, focal adhesion at the rear and at the front of MDA-MB-231 cells should be expected on fibronectin. Furthermore, the functional unit of focal contacts includes a lot of intracellular proteins (FAK, vinculin, talin, actin, etc.) (1, 7). This gives rise to a significant increase of the local , as measured in Bereiter-Hahn et al. (37). Next, the presence of extracellular components such as glycocalyx on adhesion plaques will also influence the effective refractive index. Thus, needs to be higher on focal adhesion zones. In other words, focal adhesion regions should appear where the plasma membrane closely approaches the substrate (i.e., 50 nm) and the effective refractive index is high (i.e., 1.37). This approach to localize focal adhesion regions by taking into account the cell/substrate distance and the cytoplasmic refractive index, is not new in the literature. In fact, this is the basis of interference reflection microscopy and RICM images analysis to recognize cell/substrate attachments (37, 43). However, it should be interesting to identify integrin-based focal contacts on Figs. 5 and 6, to confirm the role of integrin . This requires us to implement a second source of light on our setup to selectively excite another fluorescent molecule linked specifically to integrins. Such types of investigations are behind the scope of this article, which is rather devoted to show the feasibility and the reliability of our technique.

Table 1.

Membrane/Substrate Distance Evaluation on Some Close Contacts

Regarding the error (see Figs. 5, C and D, and 6, E and F), the error distribution is very narrow and is typically comprised between 5 and 20 nm, with a mean value ≈ 15 nm. To confirm that the axial precision of our technique is typically 10–20 nm, vaTIRFM was used on two different control samples. One easy way to characterize the axial resolution of any imaging technique is to study its response to a uniform thin planar object. For this purpose, we simply used a monolayer of QDs fixed at a glass/water interface. This sample was also applied to calibrate the incident angle (32) and to determine the illumination (x,y)-profile (Figs. S2 and S4). This QD monolayer (which is precisely located at the interface, i.e., = 0) was detected at = −2 nm, with a standard deviation = 15 nm. As a result, the axial instrumental response of vaTIRFM was typically ∼15 nm. We have also examined the height profile of a lipid membrane around adhesion patches appearing when biotinylated vesicles encounter a streptavidin-coated substrate. In this case, adhesion process is related to the specific binding between biotin proteins present on the lipid membrane and streptavidin fixed on the coverslip, as illustrated in Fig. S9. More details about vesicle and surface preparation were given in a previous publication (44). As previously depicted, the specific recognition between biotin and streptavidin will give rise to adhesion patches that clearly appear on vaTIRFM image in Fig. S9 (44). The axial profile plotted in Fig. S9 reveals the contour of the lipid membrane around a small adhesion patch. The height between the free membrane and the one linked to the substrate was ∼25 nm, which gives experimental evidence that the axial resolution of vaTIRFM is at least 25 nm. This is quite similar to the axial resolution achieved with other superresolution techniques, such as interferometric PALM (7), supercritical-angle STORM (16), or metal-induced energy transfer microscopy (15). As previously explained, cannot be estimated properly on the edge of the cell, because the membrane is curved and we excite simultaneously the dorsal and ventral sides of the cell. As a result, the error is maximum along the contour of the cell and on filopodia (see Figs. 5 C and 6 E).

Conclusions

We propose in this article a new strategy, to our knowledge, to manage variable-angle TIRF microscopy, to explore quantitatively the adhesion of living cells. By observing only the cell membrane in contact with the substrate, we have demonstrated that a series of 10 TIRF images recorded for different incident angles is useful to reconstruct the topography of motile cells with a nanometric axial resolution. The extreme axial resolution achievable with our nondestructive method, 10–20 nm, is remarkable and well adapted to quantify precisely cell adhesion processes.

Compared to previous approaches, we proposed several new, to our knowledge, strategies that yield an easier-to-use vaTIRFM. First, we introduced a new straightforward prismless setup that offers a fine control of the incident angle, with no distortion of the illumination. Moreover, we developed a complete theory that proposes new, to our knowledge, data processing to restore the cell topography. We have notably shown that it does not require a perfect knowledge of the refractive indices of all the layers that compose a cell in adhesion. Only an effective index is required. The value was also precisely determined, as well as the membrane/substrate distance. Furthermore, we have shown that it is not necessary to know accurately some parameters that affect the TIRF signal, such as the absorption cross section, the detection efficiency, and the quantum yield, commonly related to the dye orientation and its distance from the substrate.

By monitoring the distance from the substrate to the cell membrane together with the effective refractive index , it appeared possible to localize the focal adhesion zones without any specific labeling of proteins involved in the focal adhesion units. Moreover, the long axial working range of vaTIRFM (300–400 nm) is well suited to probe nonspecific interactions—for example, steric repulsion induced by a membrane component such as the glycocalyx. More interestingly, vaTIRFM enables us to follow the dynamic of adhesion during the displacement of the cell above the substrate (see Movie S1 in the Supporting Material). One can observe, in this movie, the singular localization of close contacts in time, especially when the rear of the cell is retracted. The distance distribution is also clearly affected during the cell motion. This movie highlights the real opportunities offered by vaTIRFM to examine cell-substrate interactions, for example to follow attachment/detachment kinetics on various functionalized substrates. After a relevant improvement of the theoretical description, vaTIRFM can be also extended to observe other biological structures such as the actin cortex.

Author Contributions

M.C.D.S. designed the TIRF setup and performed vaTIRF measurements on MDA-MB-231 cells; R.J. designed the TIRF setup, supervised the experiments, developed the vaTIRFM theory and the data processing, and wrote the article; C.V. developed the data processing routine on IGOR Pro software and co-supervised the experiments; and R.D. developed the vaTIRF acquisition software that controlled the rotation stage and the camera.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Hamid Morjani for providing MDA-MB-231 cells, Martin Oheim for fruitful discussions, and Christophe Couteau for his careful reading of this article.

This work was supported by the Conseil Régional Champagne-Ardenne, the Fonds Européen de Développement Régional: CELLnanoFLUO project, and the Ligue Contre le Cancer (Comité de l’Aube).

Editor: Christopher Yip.

Footnotes

Marcelina Cardoso Dos Santos’ present address is Institut d’Electronique Fondamentale, UMR CNRS 8622, Université Paris-Sud, Bâtiment 220 rue André Ampère, Centre Scientifique d’Orsay, 91 405 Orsay Cedex, France.

Nine figures and one movie are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(16)30613-0.

Supporting Material

Modification of cell topography during its displacement above a substrate coated with a thin layer of fibronectin.

References

- 1.Geiger B., Spatz J.P., Bershadsky A.D. Environmental sensing through focal adhesions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:21–33. doi: 10.1038/nrm2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sackmann E., Bruinsma R.F. Cell adhesion as wetting transition? ChemPhysChem. 2002;3:262–269. doi: 10.1002/1439-7641(20020315)3:3<262::AID-CPHC262>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hogan B., Babataheri A., Husson J. Characterizing cell adhesion by using micropipette aspiration. Biophys. J. 2015;109:209–219. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Visser C.W., Gielen M.V., Sun C. Quantifying cell adhesion through impingement of a controlled microjet. Biophys. J. 2015;108:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.10.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sariisik E., Popov C., Benoit M. Decoding cytoskeleton-anchored and non-anchored receptors from single-cell adhesion force data. Biophys. J. 2015;109:1330–1333. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.07.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hakkinen K.M., Harunaga J.S., Yamada K.M. Direct comparisons of the morphology, migration, cell adhesions, and actin cytoskeleton of fibroblasts in four different three-dimensional extracellular matrices. Tissue Eng. A. 2011;17:713–724. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanchanawong P., Shtengel G., Waterman C.M. Nanoscale architecture of integrin-based cell adhesions. Nature. 2010;468:580–584. doi: 10.1038/nature09621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Partridge M.A., Marcantonio E.E. Initiation of attachment and generation of mature focal adhesions by integrin-containing filopodia in cell spreading. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:4237–4248. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-06-0496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Limozin L., Sengupta K. Quantitative reflection interference contrast microscopy (RICM) in soft matter and cell adhesion. ChemPhysChem. 2009;10:2752–2768. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200900601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paszek M.J., DuFort C.C., Weaver V.M. The cancer glycocalyx mechanically primes integrin-mediated growth and survival. Nature. 2014;511:319–325. doi: 10.1038/nature13535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Limozin L., Sengupta K. Modulation of vesicle adhesion and spreading kinetics by hyaluronan cushions. Biophys. J. 2007;93:3300–3313. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.105544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sackmann E., Smith A.-S. Physics of cell adhesion: some lessons from cell-mimetic systems. Soft Matter. 2014;10:1644–1659. doi: 10.1039/c3sm51910d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paszek M.J., DuFort C.C., Weaver V.M. Scanning angle interference microscopy reveals cell dynamics at the nanoscale. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:825–827. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cade N.I., Fruhwirth G.O., Richards D. Fluorescence axial nanotomography with plasmonics. Faraday Discuss. 2015;178:371–381. doi: 10.1039/c4fd00198b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chizhik A.I., Rother J., Enderlein J. Metal-induced energy transfer for live cell nanoscopy. Nat. Photonics. 2014;8:124–127. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bourg N., Mayet C., Leveque-Fort S. Direct optical nanoscopy with axially localized detection. Nat. Photonics. 2015;9:587–593. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deschamps J., Mund M., Ries J. 3D superresolution microscopy by supercritical angle detection. Opt. Express. 2014;22:29081–29091. doi: 10.1364/OE.22.029081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winterflood C.M., Ruckstuhl T., Seeger S. Nanometer axial resolution by three-dimensional supercritical angle fluorescence microscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010;105:108103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.108103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hein B., Willig K.I., Hell S.W. Stimulated emission depletion (STED) nanoscopy of a fluorescent protein-labeled organelle inside a living cell. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:14271–14276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807705105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wäldchen S., Lehmann J., Sauer M. Light-induced cell damage in live-cell super-resolution microscopy. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:15348. doi: 10.1038/srep15348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lanni F., Waggoner A.S., Taylor D.L. Structural organization of interphase 3T3 fibroblasts studied by total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy. J. Cell Biol. 1985;100:1091–1102. doi: 10.1083/jcb.100.4.1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burmeister J.S., Truskey G.A., Reichert W.M. Quantitative analysis of variable-angle total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (VA-TIRFM) of cell/substrate contacts. J. Microsc. 1994;173:39–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1994.tb03426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Axelrod D., Hellen E.H., Fulbright R.M. Total internal reflection fluorescence. In: Lakowicz J.R., editor. Topics in Fluorescence Spectroscopy, Vol. 3: Biochemical Application. Plenum Press; Berlin, Germany: 1992. pp. 289–343. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dos Santos M.C., Déturche R., Jaffiol R. Axial nanoscale localization by normalized total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy. Opt. Lett. 2014;39:869–872. doi: 10.1364/OL.39.000869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mertz J. Radiative absorption, fluorescence, and scattering of a classical dipole near a lossless interface: a unified description. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B. 2000;17:1906–1913. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gingell D., Todd I., Bailey J. Topography of cell-glass apposition revealed by total internal reflection fluorescence of volume markers. J. Cell Biol. 1985;100:1334–1338. doi: 10.1083/jcb.100.4.1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olveczky B.P., Periasamy N., Verkman A.S. Mapping fluorophore distributions in three dimensions by quantitative multiple angle-total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy. Biophys. J. 1997;73:2836–2847. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78312-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loerke D., Stühmer W., Oheim M. Quantifying axial secretory-granule motion with variable-angle evanescent-field excitation. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2002;119:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00178-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lassalle H.-P., Baumann H., Schneckenburger H. Cell-substrate topology upon ALA-PDT using variable-angle total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (VA-TIRFM) J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 2007;26:83–88. doi: 10.1615/jenvironpatholtoxicoloncol.v26.i2.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Axelrod D. Selective imaging of surface fluorescence with very high aperture microscope objectives. J. Biomed. Opt. 2001;6:6–13. doi: 10.1117/1.1335689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boulanger J., Gueudry C., Salamero J. Fast high-resolution 3D total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy by incidence angle scanning and azimuthal averaging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:17164–17169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414106111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cardoso Dos Santos M., Vezy C., Jaffiol R. Membrane-substrate separation distance assessed by normalized total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy. Proc. SPIE. 2014;8949:89491H. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johansson S., Svineng G., Lohikangas L. Fibronectin-integrin interactions. Front. Biosci. 1997;2:d126–d146. doi: 10.2741/a178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Axelrod D. Carbocyanine dye orientation in red cell membrane studied by microscopic fluorescence polarization. Biophys. J. 1979;26:557–573. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(79)85271-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gingell D., Heavens O.S., Mellor J.S. General electromagnetic theory of total internal reflection fluorescence: the quantitative basis for mapping cell-substratum topography. J. Cell Sci. 1987;87:677–693. doi: 10.1242/jcs.87.5.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reichert W.M., Truskey G.A. Total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy. I. Modelling cell contact region fluorescence. J. Cell Sci. 1990;96:219–230. doi: 10.1242/jcs.96.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bereiter-Hahn J., Fox C.H., Thorell B. Quantitative reflection contrast microscopy of living cells. J. Cell Biol. 1979;82:767–779. doi: 10.1083/jcb.82.3.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Przibilla S., Dartmann S., Kemper B. Sensing dynamic cytoplasm refractive index changes of adherent cells with quantitative phase microscopy using incorporated microspheres as optical probes. J. Biomed. Opt. 2012;17 doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.17.9.097001. 97001–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gardner S.J., White N., Meek K.M. Measuring the refractive index of bovine corneal cells using quantitative phase imaging. Biophys. J. 2015;109:1592–1599. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.08.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bartsch J.E., Staren E.D., Appert H.E. Adhesion and migration of extracellular matrix-stimulated breast cancer. J. Surg. Res. 2003;110:287–294. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4804(03)00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wong N.C., Mueller B.M., Smith J.W. αv integrins mediate adhesion and migration of breast carcinoma cell lines. Clin. Exp. Metastasis. 1998;16:50–61. doi: 10.1023/a:1006512018609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mierke C.T., Frey B., Fabry B. Integrin α5β1 facilitates cancer cell invasion through enhanced contractile forces. J. Cell Sci. 2011;124:369–383. doi: 10.1242/jcs.071985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klein K., Rommel C.E., Spatz J.P. Cell membrane topology analysis by RICM enables marker-free adhesion strength quantification. Biointerphases. 2013;8:28. doi: 10.1186/1559-4106-8-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cardoso Dos Santos M., Vézy C., Jaffiol R. Nanoscale characterization of vesicle adhesion by normalized total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1858:1244–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Modification of cell topography during its displacement above a substrate coated with a thin layer of fibronectin.