Abstract

Backgrounds:

Lichen planus is a chronic systemic disease and oral mucosa is commonly involved. Oral lichen planus (OLP) most commonly affects middle-aged women. The prevalence of the disease ranges between 0.5% and 2.6% in the general population and the range of malignant transformation varies between 0% and 10%.

Objectives:

To assess the rate of malignant transformation of OLP samples.

Materials and Methods:

This retrospective study was carried out on 112 medical records of patients with histological diagnosis of OLP who attended the Department of Pathology at the Educational Hospital from 2005 to 2012. H&E-stained slides were reviewed by two pathologists using strict clinical and histopathological diagnostic World Health Organization (WHO) criteria. Dysplastic changes were diagnosed and graded according to the latest WHO classification.

Results:

Of the 112 cases diagnosed as OLP, there were 39 males and 73 females and the patients’ ages ranged from 15 to 86 years (mean age 44.5 years). The erosive form with fifty cases was the most common clinical type and the papular type with one case was the least common clinical type. Regarding the site, the buccal mucosa was the most common site with 52 cases. Totally, dysplastic changes were found in 12 samples, among them five cases showed mild dysplasia and seven cases showed moderate dysplasia. One case developed oral squamous cell carcinoma after 3 years.

Conclusion:

OLP is considered as a premalignant condition by the WHO and several authors. Although the malignancy rate is not so high, to reduce morbidity and mortality from cancer arising on OLP lesions, a regular follow-up examination is recommended.

Keywords: Oral lichen planus, precancerous condition, squamous cell carcinoma

INTRODUCTION

Lichen planus is a chronic systemic disease and oral mucosa is commonly involved; however, the involvement of other sites such as skin, vulvar, vaginal mucosa and nails has also been reported.[1] Oral lichen planus (OLP) most commonly affects middle-aged women.[2] The prevalence of the disease ranges between 0.5% and 2.6% in the general population.[3] The etiology of OLP is not clear, but immune dysregulation has been proposed to explain pathogenesis.[4] The most characteristic clinical feature of OLP is the presence of reticular white striations and/or white papules. In addition, plaque-type, atrophic/erosive, ulcerative and bullous lesions may be present at the time of diagnosis.[2,5] The buccal mucosa, dorsum of tongue and gingiva are the most common sites involved.[5,6]

A case of squamous cell carcinoma arising in OLP was first described by Hallopeau in 1910.[7] Since then, several retrospective studies and case reports have described the malignant transformation in OLPs.[8] The World Health Organization (WHO) has considered OLP as a premalignant lesion. The range of malignant transformation varies between 0% and 10%.[9,10,11] The risk of OLPs for malignant transformation is a controversial issue and remains a subject of debate in the literature. A previous series showed an equal gender distribution regarding malignant transformation with higher frequency in patients aged over 40 years. This study found the tongue as the most common site involved, followed by the buccal mucosa. Besides, the malignant transformation was mostly observed in the erosive type.[12]

This study aimed to review OLP cases and assess the prevalence of malignant transformation, as well as describe the clinico-pathological features of the cases that had premalignant changes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This retrospective study was carried out on 112 medical records of patients with a histological diagnosis of OLP who attended the Department of Pathology at The Educational Hospital from 2005 to 2012. The clinical forms of OLP were recorded as the reticular, papular and plaque-like, atrophic, erosive and bullous forms. H&E-stained slides were reviewed by two pathologists using strict clinical and histopathological diagnostic, modified WHO criteria.[13] The clinical criteria included the presence of bilateral, more or less symmetrical lesions, presence of a lace-like network of slightly raised gray-white lines (reticular pattern). Besides, erosive, atrophic, bulbous and plaque-type lesions were only accepted as a subtype in the presence of reticular lesions. The histopathological criteria were the presence of a well-defined band-like zone of cellular infiltration confined to the superficial part of the connective tissue, consisting mainly of lymphocytes and signs of liquefaction degeneration in the basal cell layer.[13] Moreover, in our study, all included patients had skin lichen planus. Dysplastic changes were diagnosed and graded according to the latest WHO classification,[14,15] which included the changes in the basilar and parabasilar portions of the epithelium in the cases of mild to moderate dysplasia which extended to the entire thickness of the epithelium in cases of severe dysplasia. The examined criteria were enlarged nuclei and cells, large and prominent nucleoli, increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, hyperchromatic and pleomorphic nuclei, bulbous or teardrop-shaped rete ridges, loss of polarity and loss of typical epithelial cell cohesiveness. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS version 21(NY, IBM Corp), the Chi-square test and Fisher's exact test. Statistical significance between the groups was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

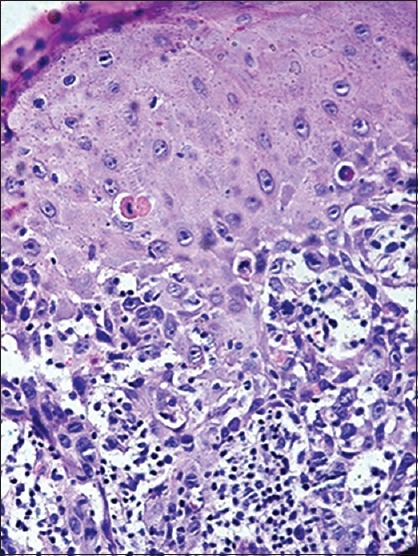

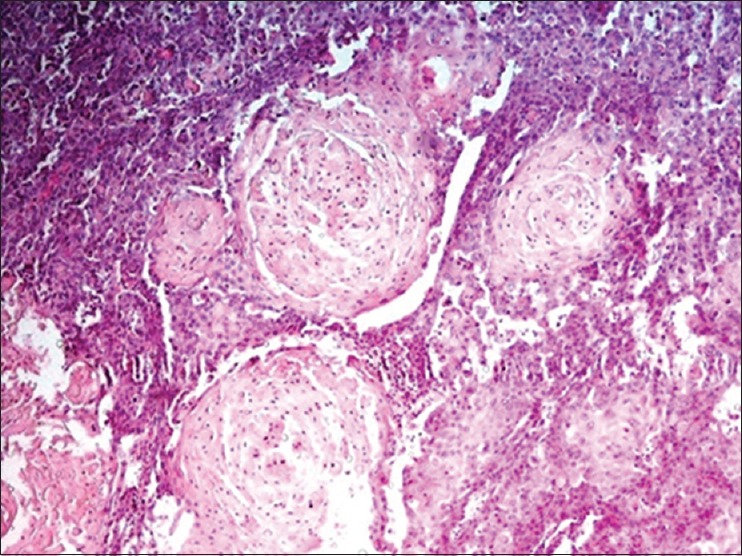

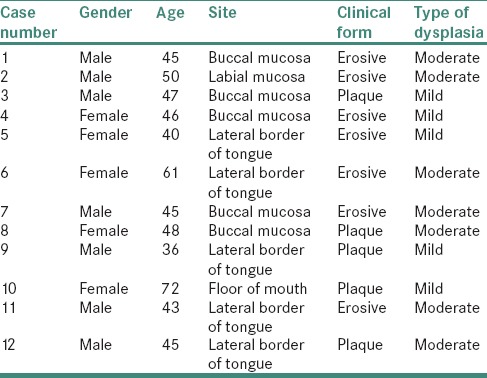

One hundred and twelve cases were diagnosed as OLP. There were 39 males and 83 females and the male to female ratio was 1:1.8. The patients’ ages ranged from 15 to 86 years (mean age 44.5 years). Regarding the clinical form, the erosive form was found in fifty cases (44.6%), the reticular form in 28 cases (%25), the plaque-like form in 23 cases (20.5%), the atrophic form in eight cases (7.1%), bullous type in two cases (1.8%) and papular type in one case (0.9%). With regard to the site, the buccal mucosa was the most common site with 52 cases (46.4%), followed by the gingiva with 26 cases (23.2%). The less common sites were the labial mucosa, tongue each with 15 cases (13.4%) and floor of mouth with four cases (3.6%). Totally, dysplastic changes were found in 12 samples (10.7%). Among them, five samples (4.5%) showed mild dysplasia and seven cases (6.2%) showed moderate dysplasia [Figure 2]. One case (case number 6) developed oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) after 3 years [Figures 3 and 4]. The statistical analysis did not show any significant differences between dysplastic changes and other variables including age, gender, site and the type of OLP. The characteristics of patients with dysplastic changes are summarized in Table 1.

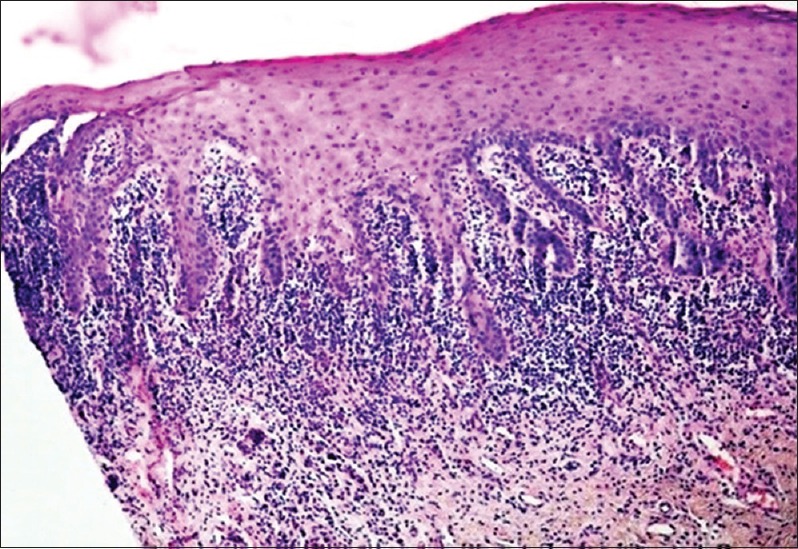

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph shows moderate dysplastic changes in oral lichen planus (H&E stain, ×250)

Figure 3.

Photomicrograph shows moderate dysplasia in the case number 6 at the time of diagnosis of oral lichen planus (H&E stain, ×400)

Figure 4.

Photomicrograph shows development of oral squamous cell carcinoma in the case number 6 after 3 years (H&E stain, ×250)

Table 1.

The characteristics of patients with dysplastic changes

DISCUSSION

This study involved OLP patients diagnosed on the basis of both clinical and histopathological criteria.[13] In our series, there was not a significant difference between patients with dysplastic changes regarding the gender. In addition, most of the patients were over 40 years of age. These findings contrast with Al-Bayati survey which has found malignant transformation in four patients (three females, one male) all aged 57 years.[16] In the present study, the most common sites of where the dysplastic changes were noted include the tongue and buccal mucosa with five cases each; however, Fang et al. found tongue as the most frequent site of malignant transformation, followed by the buccal mucosa.[12] In addition, Mattsson et al. in a study on various types of OLP showed a varied rate of malignant transformation. In this study, the reticular type was the more frequent clinical type (33% of all OLP cases) developing a malignancy and the atrophic type was the least common clinical type (13%, of all cases) with malignant transformation.[17] In the present study, seven cases (58.3%) of all cases with dysplastic changes were clinically diagnosed as erosive type and remaining five cases (41.7%) presented clinically as plaque-type.

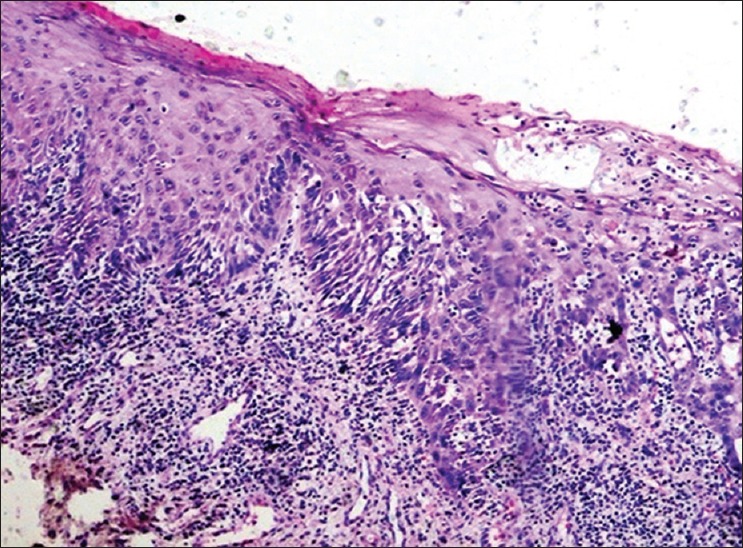

In the present series, 10.7% of the 112 cases developed dysplastic changes. Among them, 4.5% showed mild dysplasia [Figure 1] and 6.2% showed moderate dysplasia [Figure 2]. In Werneck et al. study, 47.6% of the samples showed mild dysplastic changes and 4.76% showed moderate epithelial dysplasia.[18] In a study of 502 patients carried out by Mignogna et al., a malignancy developed at sites previously diagnosed as OLP in 4.8% of cases.[11] Bermejo–Fenoll et al. showed 0.90% of malignant transformation in 550 cases of OLP.[19] In Bardellini et al. study, 2 out of 204 patients (0.98%) developed squamous cell carcinoma at a previously diagnosed OLP site,[20] and Xue et al. found malignant transformation at sites previously diagnosed as erosive lichen planus.[21] However, Reed in a study on 67 cases of OLP did not detect any malignant changes in the OLP group.[22] The presence of oral epithelial dysplasia is one of the most important predictors of malignant development in premalignant disorders.[23]

Figure 1.

Photomicrograph shows mild dysplastic changes in oral lichen planus (H&E stain, ×40)

The preferential sites of OSCCs which develop from OLP lesions are the tongue and buccal mucosa, and the incidence is higher in the former than in the latter.[24] However, epithelial dysplasia is more prevalent in OLPs which develops in the buccal mucosa.[25] Interestingly, in some cases, OSCC has arisen on the dorsum of the tongue, a rare location for OSCC, from the plaque-type.[26,27] Though, the red lesions, such as erosive and atrophic forms of OLP, are more associated with progression to OSCC.[28]

Exposure to some carcinogens such as smoking and alcohol has been suggested to increase the risk of transformation.[11] In the present study, none of the patients had a history of tobacco use or alcohol consumption.

The WHO considers OLP as a precancerous lesion, especially in the presence of dysplasia.[29] Krutchkoff et al. reviewed previous reports and indicated that there was not sufficient evidence for the malignant transformation of OLP.[9] Krutchkoff and Eisenberg have suggested the term lichenoid dysplasia for cases of OLP with dysplasia. They believed that some reported cases of OLP with a malignancy were misdiagnosed from the beginning.[25,30] These authors proposed histopathological and/or clinicopathological diagnostic criteria; however, these criteria have not been validated.[31] In addition, both OLP and OSCC are not rare diseases; therefore, it is assumed that they may develop simultaneously.[15] On the other hand, there are some reports of developing a malignancy in the same site previously diagnosed as OLP.[27,32,33]

The etiology of OLP is unknown, but it is considered as an autoimmune process. It is suggested that keratinocytes express an antigen resulting in the activation of cytotoxic CD8 T-lymphocytes and CD4 T-lymphocytes by different mechanisms inducing the destruction of the epithelial basal membrane, degeneration of the basal layer and cellular apoptosis.[34,35] To maintain oral epithelial integrity, cellular turnover rate increases. Some authors believe that both apoptosis and increased cellular proliferation occur simultaneously.[36,37] The recent publications indicate that chronic inflammation promotes cell survival, growth, proliferation and differentiation by producing different cytokines. These factors may contribute to cancer initiation, promotion and progression.[38] Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) is a cytokine which induces neoplastic process and angiogenesis. TNF involvement in the pathogenesis of OLP has been proven.[39]

Several attempts have been made to identify OLP patients with a risk of future malignant development. The altered expression level of proteins related to cell apoptosis and proliferation rate can be used as predictive indicators for high risk of malignant transformation. In a study on the expression levels of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) in erosive and plaque-type OLP, cases of the erosive type showed higher expression level (66.86%) compared to those of the plaque-type (17.08%).[40] It has been concluded that the gradual increase of PCNA expression level in normal epithelial cells into dysplastic epithelial cells indicates an increased proliferative activity with disease progression.[41] Another study indicated a strong positive staining for Ki-67 (42.9%) in all OLP samples.[42] The expression level of p53 was investigated in the saliva of OLP and OSCC patients. In that series, the p53 positivity was found in 35% of OLP group which was significantly higher than that of the control group. Importantly, the p53 positivity was significantly higher in reticular form (47%) than in erosive form (23%).[43] In addition, another study proposed that higher expression levels of P53 and p21 in OLP samples compared to normal tissues may indicate the precancerous potential of OLPs.[44] Besides, Bcl-2 positivity was found in 23.3% of OSCC samples and 19.9% of the OLP samples.[23] In another study, CD133 positivity was found in 29% of cases of OLP without malignant transformation and 80% of cases who developed OSCC at a site previously diagnosed as OLP.[45] In a study on ten cases of severe OLP, deposition of complements was investigated. Granular deposition of C3 was found in oral mucosal basement membrane zone. It was suggested that granular C3 deposition may be one of the characteristic features of severe OLP.[46]

A reticular form of OLP does not need any treatment and erosive type of OLP responds to systemic corticosteroids. It is highly recommended to follow-up the patients every 3–6 months.[47]

CONCLUSION

OLP is considered as a potentially malignant disorder by the WHO and several authors.[2,8,11,27,31,32] Although the malignancy rate is not so high to reduce morbidity and mortality from cancer arising on OLP lesions, a regular follow-up examination is recommended not only because of malignant potential but also due to possible mistakes in the diagnosis from the beginning. Therefore, strict clinical and histological studies need to be done to resolve the controversies.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported by Hamadan University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Hashimi I, Schifter M, Lockhart PB, Wray D, Brennan M, Migliorati CA, et al. Oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: Diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:S25.e1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.11.001. Epub 2007 Jan 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sugerman PB, Savage NW. Oral lichen planus: Causes, diagnosis and management. Aust Dent J. 2002;47:290–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2002.tb00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ikeda N, Handa Y, Khim SP, Durward C, Axéll T, Mizuno T, et al. Prevalence study of oral mucosal lesions in a selected Cambodian population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1995;23:49–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1995.tb00197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Irani S, Monsef Esfahani AR, SabetiSH, Bidari Zerehpoush F. Detection of Helicobacter pylori in oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid reaction. Avicenna J Dent Res. 2014;6:e23213. doi: 10.5681/joddd.2013.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones KB, Jordan R. White lesions in the oral cavity: Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2015;34:161–70. doi: 10.12788/j.sder.2015.0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pinholt EM, Rindum J, Pindborg JJ. Oral cancer: A retrospective study of 100 Danish cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;35:77–80. doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(97)90679-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalez-Moles MA, Scully C, Gil-Montoya JA. Oral lichen planus: Controversies surrounding malignant transformation. Oral Dis. 2008;14:229–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2008.01441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Meij EH, Mast H, van der Waal I. The possible premalignant character of oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: A prospective five-year follow-up study of 192 patients. Oral Oncol. 2007;43:742–8. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krutchkoff DJ, Cutler L, Laskowski S. Oral lichen planus: The evidence regarding potential malignant transformation. J Oral Pathol. 1978;7:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1978.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eisenberg E, Krutchkoff DJ. Lichenoid lesions of oral mucosa. Diagnostic criteria and their importance in the alleged relationship to oral cancer. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;73:699–704. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(92)90013-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mignogna MD, Lo Muzio L, Lo Russo L, Fedele S, Ruoppo E, Bucci E. Clinical guidelines in early detection of oral squamous cell carcinoma arising in oral lichen planus: A 5-year experience. Oral Oncol. 2001;37:262–7. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(00)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang M, Zhang W, Chen Y, He Z. Malignant transformation of oral lichen planus: A retrospective study of 23 cases. Quintessence Int. 2009;40:235–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Meij EH, van der Waal I. Lack of clinicopathologic correlation in the diagnosis of oral lichen planus based on the presently available diagnostic criteria and suggestions for modifications. J Oral Pathol Med. 2003;32:507–12. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2003.00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Speight PM. Update on oral epithelial dysplasia and progression to cancer. Head Neck Pathol. 2007;1:61–6. doi: 10.1007/s12105-007-0014-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neville B, Damm D, Allen C, Chi A. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noguti J, De Moura CF, De Jesus GP, Da Silva VH, Hossaka TA, Oshima CT, et al. Metastasis from oral cancer: An overview. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2012;9:329–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mattsson U, Jontell M, Holmstrup P. Oral lichen planus and malignant transformation: Is a recall of patients justified? Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2002;13:390–6. doi: 10.1177/154411130201300503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Werneck JT, Costa Tde O, Stibich CA, Leite CA, Dias EP, Silva Junior A. Oral lichen planus: Study of 21 cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:321–6. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bermejo-Fenoll A, Sanchez-Siles M, López-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Salazar-Sanchez N. Premalignant nature of oral lichen planus. A retrospective study of 550 oral lichen planus patients from south-eastern Spain. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:e54–6. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bardellini E, Amadori F, Flocchini P, Bonadeo S, Majorana A. Clinicopathological features and malignant transformation of oral lichen planus: A 12-years retrospective study. Acta Odontol Scand. 2013;71:834–40. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2012.734407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xue JL, Fan MW, Wang SZ, Chen XM, Li Y, Wang L. A clinical study of 674 patients with oral lichen planus in China. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;34:467–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2005.00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reed SG. Oral lichenoid lesions and not oral lichen planus have the character for malignant transformation to oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2008;8:238–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shailaja G, Kumar JV, Baghirath PV, Kumar U, Ashalata G, Krishna AB. Estimation of malignant transformation rate in cases of oral epithelial dysplasia and lichen planus using immunohistochemical expression of Ki-67, p53, BCL-2, and BAX markers. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2015;12:235–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bombeccari GP, Guzzi G, Tettamanti M, Giannì AB, Baj A, Pallotti F, et al. Oral lichen planus and malignant transformation: A longitudinal cohort study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112:328–34. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krutchkoff DJ, Eisenberg E. Lichenoid dysplasia: A distinct histopathologic entity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1985;60:308–15. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(85)90315-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eisen D. The evaluation of cutaneous, genital, scalp, nail, esophageal, and ocular involvement in patients with oral lichen planus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;88:431–6. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(99)70057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Irani S. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in oral lichen planus: A case report. DJH. 2010;1:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scully C, el-Kom M. Lichen planus: Review and update on pathogenesis. J Oral Pathol. 1985;14:431–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1985.tb00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holmstrup P. The controversy of a premalignant potential of oral lichen planus is over. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;73:704–6. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(92)90014-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eisenberg E. Oral lichen planus: A benign lesion. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:1278–85. doi: 10.1053/joms.2000.16629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gandolfo S, Richiardi L, Carrozzo M, Broccoletti R, Carbone M, Pagano M, et al. Risk of oral squamous cell carcinoma in 402 patients with oral lichen planus: A follow-up study in an Italian population. Oral Oncol. 2004;40:77–83. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(03)00139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gándara-Rey JM, Freitas MD, Vila PG, Carrión AB, Peñaranda JMS, Garcia GA. Malignant transformation of oral lichen planus in lingual location: Report of a case. Oral Oncol Extra. 2004;40:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fitzpatrick SG, Hirsch SA, Gordon SC. The malignant transformation of oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: A systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145:45–56. doi: 10.14219/jada.2013.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lodi G, Scully C, Carrozzo M, Griffiths M, Sugerman PB, Thongprasom K. Current controversies in oral lichen planus: Report of an international consensus meeting. Part 1. Viral infections and etiopathogenesis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.06.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mattila R, Syrjänen S. Caspase cascade pathways in apoptosis of oral lichen planus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;110:618–23. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.05.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tobón-Arroyave SI, Villegas-Acosta FA, Ruiz-Restrepo SM, Vieco-Durán B, Restrepo-Misas M, Londoño-López ML. Expression of caspase-3 and structural changes associated with apoptotic cell death of keratinocytes in oral lichen planus. Oral Dis. 2004;10:173–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1601-0825.2003.00998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mattila R, Alanen K, Syrjänen S. Immunohistochemical study on topoisomerase IIalpha, Ki-67 and cytokeratin-19 in oral lichen planus lesions. Arch Dermatol Res. 2007;298:381–8. doi: 10.1007/s00403-006-0711-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Irani S, Monsef Esfahani A, Bidari Zerehpoush F. Detection of Helicobacter pylori in oral lesions. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects. 2013;7:230–7. doi: 10.5681/joddd.2013.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sugermann PB, Savage NW, Seymour GJ, Walsh LJ. Is there a role for tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) in oral lichen planus? J Oral Pathol Med. 1996;25:219–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1996.tb01375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Redder CP, Pandit S, Desai D, Kandagal VS, Ingaleshwar PS, Shetty SJ, et al. Comparative analysis of cell proliferation ratio in plaque and erosive oral lichen planus: An immunohistochemical study. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2014;11:316–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chiang CP, Lang MJ, Liu BY, Wang JT, Leu JS, Hahn LJ, et al. Expression of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) in oral submucous fibrosis, oral epithelial hyperkeratosis and oral epithelial dysplasia in Taiwan. Oral Oncol. 2000;36:353–9. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pigatti FM, Taveira LA, Soares CT. Immunohistochemical expression of Bcl-2 and Ki-67 in oral lichen planus and leukoplakia with different degrees of dysplasia. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:150–5. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Agha-Hosseini F, Mirzaii-Dizgah I, Miri-Zarandi N. Unstimulated salivary p53 in patients with oral lichen planus and squamous cell carcinoma. Acta Med Iran. 2015;53:439–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Safadi RA, Al Jaber SZ, Hammad HM, Hamasha AA. Oral lichen planus shows higher expressions of tumor suppressor gene products of p53 and p21 compared to oral mucositis. An immunohistochemical study. Arch Oral Biol. 2010;55:454–61. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun L, Feng J, Ma L, Liu W, Zhou Z. CD133 expression in oral lichen planus correlated with the risk for progression to oral squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2013;17:486–9. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hashimoto T, Fukuda A, Himejima A, Morita S, Tsuruta D, Koga H, et al. Ten cases of severe oral lichen planus showing granular C3 deposition in oral mucosal basement membrane zone. Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:539–47. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2015.2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jainkittivong A, Kuvatanasuchati J, Pipattanagovit P, Sinheng W. Candida in oral lichen planus patients undergoing topical steroid therapy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;104:61–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]