Abstract

Introduction

Collaborative mental healthcare (CMHC) has garnered worldwide interest as an effective, team-based approach to managing common mental disorders in primary care. However, questions remain about how CMHC works and why it works in some circumstances but not others. In this study, we will review the evidence on one understudied but potentially critical component of CMHC, namely the engagement of patients and families in care. Our aims are to describe the strategies used to engage people with depression or anxiety disorders and their families in CMHC and understand how these strategies work, for whom and in what circumstances.

Methods and analysis

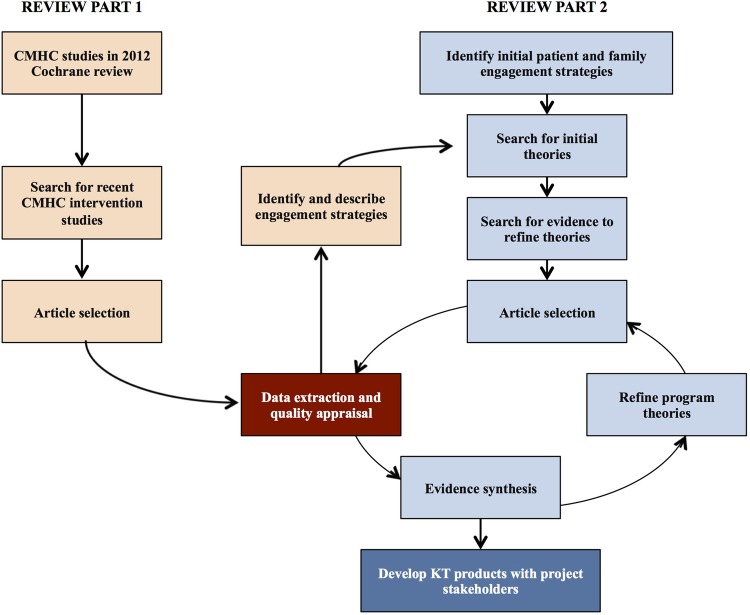

We are conducting a review with systematic and realist review components. Review part 1 seeks to identify and describe the patient and family engagement strategies featured in CMHC interventions based on systematic searches and descriptive analysis of these interventions. We will use a 2012 Cochrane review of CMHC as a starting point and perform new searches in multiple databases and trial registers to retrieve more recent CMHC intervention studies. In review part 2, we will build and refine programme theories for each of these engagement strategies. Initial theory building will proceed iteratively through content expert consultations, electronic searches for theoretical literature and review team brainstorming sessions. Cluster searches will then retrieve additional data on contexts, mechanisms and outcomes associated with engagement strategies, and pairs of review authors will analyse and synthesise the evidence and adjust initial programme theories.

Ethics and dissemination

Our review follows a participatory approach with multiple knowledge users and persons with lived experience of mental illness. These partners will help us develop and tailor project outputs, including publications, policy briefs, training materials and guidance on how to make CMHC more patient-centred and family-centred.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42015025522.

Keywords: Collaborative mental health care, Patient and family engagement, Realist review, Depression and Anxiety, Protocol

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This review is the first to describe the range of patient and family engagement strategies that have been used in collaborative care interventions for depression and anxiety disorders in primary care.

The realist synthesis will clarify how, why and in what circumstances these patient and family engagement strategies lead to intended patient, family and health system outcomes.

The review is being conducted with a participatory approach involving multiple stakeholders, including persons with lived experience of mental illness.

The specific patient and family engagement strategies we wish to study are not all known in advance and as such we may have to prioritise and focus our synthesis on a subgroup of engagement strategies during the study period.

Introduction

Rationale for the review

Major depression and anxiety disorders are among the most prevalent chronic diseases in populations and a leading cause of disease burden worldwide.1 In many countries, the bulk of care for these common mental disorders is delivered in primary care, most often by general practitioners (GPs).2–4 However, many GPs are challenged to manage depression and anxiety disorders effectively, and there are long-standing quality gaps in the diagnosis and treatment of these disorders in primary care.5–9 This has prompted the emergence of new models of care for these disorders, notably collaborative mental healthcare (CMHC). CMHC encompasses a range of team-based interventions promoting greater mutual support between providers from different specialties, disciplines and sectors and more coordinated, complimentary services to patients.10 Widely considered one of the most effective and cost-effective approaches to treating common mental disorders in primary care, it has become a focus of organised dissemination efforts internationally.10–14

One of the main challenges of implementing and scaling up CMHC is that it is a ‘complex’ model of care that comprises several interacting intervention components associated with a broad spectrum of patient and health system outcomes.15 16 Across projects and jurisdictions, CMHC has taken different forms depending on the types of providers involved, the types of patients targeted, the constraints of contexts and the types of outcomes pursued.15–18 Recent systematic reviews have shown that this diversity in CMHC contributes to diversity in effectiveness, with approximately half of CMHC interventions actually failing to produce significant improvements on intended outcomes relative to usual care.16 18 This has prompted an interest in unearthing the ‘active ingredients’ of CMHC that contribute to the model's success. Commonly cited components of CMHC are case management services provided by nurses or mental health professionals, consultation-liaison services by psychiatrists, greater use of clinical practice guidelines and evidence-based therapies, more structured detection and patient monitoring processes and new mechanisms and tools to enhance interprofessional communication and collaboration.15–18 However, efforts to assess the importance of such components using advanced review methods such as meta-analysis and meta-regression have produced mitigated results,15 17–19 and it remains unclear why CMHC is more or less effective in different settings.

One potentially critical but relatively understudied component of CMHC is the engagement of patients and families in their care. Studies show that people with mental disorders and their families prefer to be actively involved in their care20 21 and that their engagement can have many positive impacts on them and on health systems.22–25 In other domains of healthcare, patients and families are increasingly considered an integral part of interdisciplinary care teams.26 Yet, such partnerships are not as common in routine mental healthcare23 24 27 and patient and family engagement is not consistently described as a core component of CMHC for depression or anxiety disorders.12 13 15 16 18 Given active efforts to broadly disseminate CMHC around the world, it is urgent to address knowledge gaps on how to best engage patients and families within this model of care and how such engagement may contribute to the impacts of CMHC.

Although many previous systematic reviews of CMHC have been performed,12 13 15–19 28 none have focused on patient and family engagement or were designed to disentangle the complex causal relationships that exist between intervention components, participants, contexts and outcomes.29 Realist reviews offer an alternative approach to knowledge synthesis that is well adapted for complex models of care such as CMHC. Realist reviews focus on providing explanations for how and why interventions may or may not work, for whom and in what circumstances they work.29–31 Such explanations are based on investigations into the mechanisms (ie, causal forces) that underpin interventions and the contextual conditions impacting interventions' outcomes in different settings. The realist approach is considered theory-driven in that interventions are viewed as theories incarnate, made up of assumptions about how they are meant to work and what impacts they should have.31 During the realist review process, these theories about how interventions generate change (also known as programme theories) are made explicit and then compared against the existing evidence to find out whether they hold and are useful or require refinement. Programme theories thus map out the relationships between intervention contexts, components and mechanisms and outcomes.31 Realist reviews are interpretive in nature and typically draw from diverse sources of evidence, including quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods research.29 It is the appropriate method for helping us understand the complexity and potential value of patient and family engagement within CMHC.

Review question and objectives

Our overall review question is: What strategies have been used to engage people with depression or anxiety disorders and their families in CMHC and how do these strategies work, for whom and in what circumstances?

Our specific objectives are to:

Identify and describe in detail the patient and family engagement strategies used in CMHC interventions for depression or anxiety disorders.

Develop programme theories that explain the relationships between the mechanisms underlying these engagement strategies, the particular outcomes triggered by these mechanisms and the contextual factors influencing these associations.

Develop guidance and knowledge translation (KT) products that can be used to promote the implementation of more patient-centred and family-centred forms of CMHC.

Methods

This review has two parts, with part 1 (aim: identifying and describing strategies for patient and family engagement in CMHC) supporting part 2 (aim: building and refining programme theories about these patient and family engagement strategies) (figure 1). The reporting of our review will respect PRISMA guidance for systematic reviews32 and RAMESES standards for realist reviews,33 and the review protocol has been registered in the international register of systematic review protocols (number CRD42015025522; http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO). Any additional amendments to the protocol will be tracked and dated in PROSPERO.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for systematic and realist review. CMHC, collaborative mental healthcare.

Part 1: identifying patient and family engagement strategies

In order to identify and describe strategies for engaging patients and their families in CMHC, we will search the literature to retrieve all major CMHC interventions evaluated to date. Our starting point will be the 2012 Cochrane systematic review that identified 79 distinct CMHC interventions for depression and anxiety disorders in primary care.16 Since many new studies on CMHC are published each year, we will perform new searches to have the most complete list of CMHC interventions possible. Next, we will extract the data on patient and family engagement strategies from these studies and describe these strategies in detail.

Search strategy and study selection

To retrieve articles on recent CMHC interventions, an information specialist will replicate the search strategy used in the Cochrane systematic review of CMHC for depression and anxiety disorders.16 We will perform searches in the Cochrane Collaboration Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis (CCDAN; 2011 to present) and CINAHL (2009 to present) databases, as well as the WHO ICTRP and ClinicalTrials.gov trial registers. Search terms related to depression, anxiety disorders and collaborative care will be used (see online supplementary appendix 1 for CINAHL search terms). For completeness, we will also search for relevant CMHC trials in the EU Clinical Trials register.

bmjopen-2016-012949supp_appendix.pdf (89.8KB, pdf)

Eligibility criteria for intervention studies will closely resemble those used in the 2012 Cochrane review.16 Briefly, eligible studies will be randomised controlled trials and clinical controlled trials with eligible comparators that involve youth or adults with primary diagnoses of depression or anxiety disorders. Interventions will be considered as collaborative care if they fulfil four main criteria: (1) a multidisciplinary approach to care involving a primary care practitioner and at least one other health professional (eg, nurse, psychologist, psychiatrist, pharmacist, social worker), (2) a structured management plan (eg, use of guidelines or protocols, evidence-based pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy), (3) a systematic or scheduled approach to patient follow-up and (4) mechanisms for enhanced communication between providers (eg, team meetings, shared medical records, consultation/supervision). Studies must describe outcomes related to depression or anxiety symptomatology, medication use, functioning, quality of life or satisfaction with care.

Two authors will independently screen all titles and abstracts and then appraise full-texts to identify studies meeting the full eligibility criteria. Disagreements will be resolved through discussion and involvement of a third author.

Data extraction and analysis

Two authors will independently extract data from all included studies using piloted EXCEL spreadsheets and a codebook developed to ensure shared understanding of concepts. Several conceptual frameworks will be used to help establish clear definitions for data sought, including Coulter34 and Carman's35 patient engagement frameworks for data on engagement strategies, Damschroder's Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research36 for information on intervention contexts and implementation and Proctor's conceptualisation of intervention outcomes.37 For efficiency reasons, data relevant to review objectives 1 and 2 will be extracted simultaneously. We will extract data on:

Study characteristics: authors, publication date, study design, etc.

Study participants: age, sex, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, mental health condition, illness severity, comorbid conditions, etc.

CMHC interventions: types of providers involved, clinician characteristics, intervention components, type of collaboration (ie, multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary), treatments offered, etc.

Patient and family engagement strategies: type of engagement strategy, engagement level and strategy details, participants targeted, proposed mechanisms of action, outcomes pursued, etc.

Implementation processes: implementation climate, implementation strategies and steps, implementation barriers and facilitators, etc.

Intervention contexts: geographical settings, organisational settings, leadership engagement, policies and regulations, etc.

Outcomes: clinical (eg, depression or anxiety symptoms, medication use, functioning, quality of life), service-level (eg, care quality, teamwork) and implementation (intervention fidelity, adoption of engagement strategies).

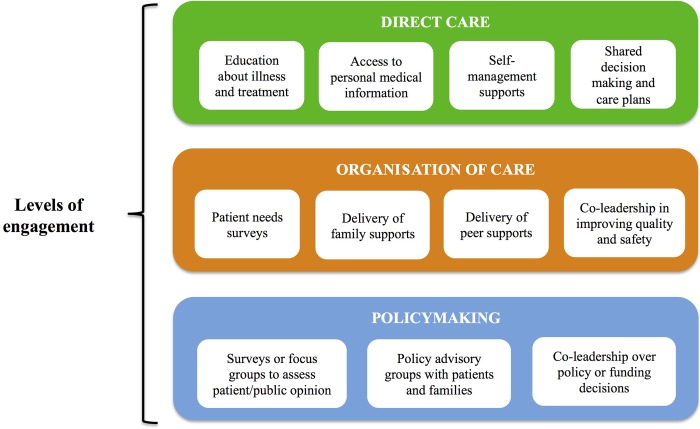

Study quality:38 recruitment/sampling, randomisation, blinding, completeness of data, measures, etc.

Once data have been extracted, two review authors will perform a thematic analysis of patient and family engagement strategies guided by the patient engagement frameworks of Coulter34 and Carman.35 We define patient and family engagement as: patients, families, their representatives and healthcare providers working together at various levels across the healthcare system to improve health and healthcare.35 Coulter identifies a range of patient-focused interventions, including those targeting health literacy, clinical decision-making, self-care and patient safety.34 Carman's framework includes three ‘levels of engagement’ (direct care, organisation of care, policymaking) and different degrees of engagement (consultation, involvement, partnership, shared leadership).35 An illustration of a preliminary combined framework is provided in figure 2. The thematic analysis will involve reading through the study articles, deductively and inductively establishing initial codes for specific engagement strategies (eg, self-management supports, peer supports) and regrouping these codes into themes consistent with our conceptual frameworks (eg, direct care strategies). The two reviewers performing the analyses will regularly share results with the larger review team in order to incorporate their views and refine the results. Through these analyses, we will be able to quantify the extent of different engagement strategies across CMHC studies and produce a rich description of these strategies as well as a refined typology based on our frameworks. Articles retrieved in part 2 of this review will serve to further enrich our descriptions of patient and family engagement strategies used in CMHC.

Figure 2.

Preliminary patient and family engagement framework.

Part 2: developing programme theory on patient and family engagement strategies

Realist reviews often have two main phases: theory building and refinement.29–31 Theory building involves formulating ‘initial rough’ programme theories that provide a basic explanation of how and why interventions are expected to work, in what circumstances they may work and what outcomes they may generate. Initial rough programme theories can take the form of provisional statements describing relationships between intervention contexts, mechanisms and outcomes (referred to as context-mechanism-outcome or CMO configurations). In the programme theory refinement phase, the initial rough theories are tested against empirical data from studies and other sources and refined in light of this new evidence. These refined programme theories are the main products of realist reviews and by examining and contrasting them, and drawing on formal theories relevant to the review (ie, from disciplines such as sociology, psychology and education), it is possible to develop more sophisticated explanations for why the CMO patterns look the way they do.31 This is the process through which we will achieve review objective 2.

Search for initial theories

Informed by review team discussions and a pilot analysis of 15 seminal articles on CMHC identified in a review of foundational CMHC articles,39 we have chosen to begin initial theory building with four patient and family engagement strategies appearing in CMHC interventions: shared decision-making and treatment planning, self-management supports, peer supports and family supports. Patient involvement in treatment planning and self-management supports were featured in 11 of the 15 seminal articles we examined, suggesting they may be commonly used strategies. Peer and family supports were much less commonly observed in our pilot analysis (adopted in only one study) but were identified by the review team as highly relevant for the realist review. Theory building will initially focus on these four strategies and continue in an iterative manner as other engagement strategies are identified in part 1 of the review.

To locate and build initial theories related to patient and family engagement strategies, we will (1) consult with content experts in our review team and potentially outside the team if necessary, (2) perform electronic searches of the scientific and grey literature to retrieve theoretical and conceptual writings on each identified patient and family engagement strategy, (3) review the introduction and discussion sections of articles on CMHC interventions retrieved in review part 1 and (4) hold brainstorming sessions to create the CMO configurations and establish a consensus on these initial rough theories. Our review team includes researchers, clinicians, KT experts, policymakers and representatives of mental health service users and families that together cover key areas of content expertise (see the ‘Involvement of review team members’ section). We will ask review team members to provide the most relevant literature describing theoretical underpinnings, contextual influences and outcomes of engagement strategies and share their own knowledge and expertise about how and why engagement strategies work, generally and within the context of interprofessional models of care such as CMHC. This work will be complemented by searches in MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO and Google Scholar using search terms for patient and family engagement strategies (eg, care planning, shared decision-making, self-management, peer support) and theory (eg, theory, concept, model, framework).40 Examples of search terms for engagement strategies will be drawn from relevant systematic reviews of these strategies.41–44 Reference lists of all relevant articles will be searched and relevant grey literature (eg, theses, websites, reports) sought through iterative searches in Google and Google Scholar. Theory building will then advance through several small-group brainstorming sessions to construct CMO configurations for each engagement strategy, and then these CMO configurations will be revisited and prioritised in a full-team consensus-building meeting supported by visualisation software.45

Search for evidence to refine theories

Some of the evidence needed to refine our initial rough programme theories will be found in the CMHC intervention studies identified in part 1 of the review. However, we will seek out additional evidence on contexts, mechanisms and outcomes pertaining to patient and family engagement strategies in CMHC and open the synthesis to a broader array of study designs and data sources.29 To retrieve this evidence, we will perform cluster searching, that is, a systematic attempt, using a variety of techniques, to identify papers or other research outputs that relate to a single study.46 Specifically, we will identify sibling studies (eg, process evaluations or qualitative studies linked to the CMHC intervention trial), reports and other forms of evidence relevant to the CMHC intervention studies identified in review part 1 that also featured patient and family engagement strategies. The cluster searching approach was designed to capture reports that can together provide rich contextual and conceptual descriptions of complex interventions.46 Our cluster searches will be performed by two review authors supported by an experienced information specialist and involve extensive reference list searches, reverse citation and author searches in Google Scholar and Web of Science, searches in Google using study names and reviews of key authors' publications and communications in ResearchGate. If necessary, we will also contact the principal investigators of CMHC studies by email to gather information and details on engagement strategies missing from published reports.

Consistent with best practices in realist reviews, at this stage we will also consider evidence from other studies of collaborative care, disease management or chronic disease care where it can be reasonably inferred that the same engagement strategy mechanisms might be in operation.29 31 Our information specialist will craft searches to help us retrieve relevant studies, using several systematic reviews in these areas as starting points.

Article selection and appraisal of relevance

Four review authors working in pairs of two will oversee the selection of evidence for the refinement of programme theories. Relevance in the study selection process will be dictated by whether the study, report or other document is able to inform our understanding of patient and family engagement strategies and their respective CMO configurations.31 Eligible documentation includes academic literature covering multiple types of research designs (eg, quantitative, qualitative, mixed-methods, evaluations, reviews), as well as a range of other data sources (eg, editorials and commentaries, study protocols, organisational reports, websites, policy documents, book chapters, conference presentations, theses). Potentially relevant documentation will be screened and flagged by review author pairs using a detailed and regularly revised guidebook and then uploaded into shared folders in Mendeley. A fifth review author will participate in the screening to crosscheck results, establish consensus on document relevance and resolve any disagreements among review author pairs.

Data extraction and quality appraisal

Once evidence from sibling studies and other sources has been retrieved and considered relevant, two reviewers will extract the data on characteristics of studies, participants, CMHC interventions, engagement strategies, implementation contexts and strategies and outcomes into Excel spreadsheets. Our appraisal of the quality of evidence used in the realist synthesis will be consistent with guidance by Pawson29 and RAMESES standards.33 Specifically, the rigour of each document or section of data will be appraised at the moment of their usage in the analysis. A subgroup within the review team with diverse methods expertise will establish minimal standards of quality for different study types (quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods) informed by the mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT)47 and meet together as needed to discuss the credibility and trustworthiness of other data sources relevant for the synthesis. The MMAT is a valid and reliable tool relevant for use in complex, mixed studies reviews as it contains criteria for appraising the methodological quality of studies with various study designs.47 For example, if data relevant to our programme theory were produced in a qualitative study, the MMAT suggests that the study is more trustworthy if the methods and analyses were described clearly and if the researchers performing the study explained how they may have influenced their results (ie, reflexivity).

Evidence synthesis

The evidence synthesis will be conducted according to a realist logic involving the iterative testing and refinement of our initial programme theories using evidence from multiple sources and subsequent generation of middle-range programme theories (ie, theories that remain close to the data but also abstracted enough to apply to a broader range of situations) that explain how and why our refined CMO configurations relate to each other. We propose a five-step analysis process. First, we will regroup all evidence related to each CMHC intervention and build ‘case summaries’ that provide rich descriptions of the interventions and the patient and family engagement strategies featured within them. These case summaries will be structured according to the TIDieR framework48 and provide a detailed account of interventions and their components, participants involved in delivering and receiving the interventions, activities related to patient and family engagement (materials, procedures, etc), implementation contexts and processes and reported outcomes. As an example, relevant information from all studies, reports and other documents related to the IMPACT programme for late life depression will be summarised to establish a detailed portrait of that particular case; the same exercise will be performed for all other CMHC interventions. These case summaries will be valuable in establishing a shared understanding of CMHC interventions across review team members. Second, six review authors working in pairs will independently analyse the documents associated with specific cases using text annotation and note taking techniques and then meet regularly as author pairs to critically discuss similarities and discrepancies in their coding and analysis. For each case, the review author pairs will have two main analytic tasks: (1) for each patient and family engagement strategy, perform a deductive analysis of documents guided by the concepts featured in our initial theories (ie, initial CMO configurations) and (2) use abduction and retroduction strategies to consider new relationships between the contexts, mechanisms and outcomes associated with each engagement strategy in the case. Abductive inference involves re-interpreting the data in order to form associations that may fall outside the initial theoretical frame, whereas retroduction relates to inferences about the conditions needed for something (eg, a mechanism or outcome) to exist.49 Third, relevant documents and analyses will be uploaded into NVivo qualitative data management software in order to code sections of text and explore and refine CMO causal linkages. Following advice from Dalkin, at this stage we will be sensitive to distinctions between mechanisms in the form of intervention resources (eg, a self-management guide) versus those related to new reasoning or reactions (eg, a patient's sense of self-efficacy).50 NVivo has proven in previous realist reviews to be a valuable tool for managing large amounts of diverse data and supporting synthesis and visualisation of emerging findings.51–53 Two review authors will oversee this phase of the synthesis and consult regularly with the larger, multidisciplinary review team to ensure transparency, consistency and reflexivity. Fourth, we will perform cross-case comparisons for interventions with similar engagement strategies and underlying mechanisms. Using techniques such as triangulation and situating, reconciling and adjudicating the evidence, we will explore how contextual features differ across these cases and how these variations affect targeted outcomes.31 Themes generated during the synthesis process will also serve to support or refute our initial theories, leading us to make refinements until a ‘best fit’ is reached. The rigour of evidence sources will also be accounted for, allowing us to make judgements about how to adjust CMO configurations as a function of stronger or weaker evidence. Finally, commonalities (or demi-regularities) across refined CMO configurations will be sought and summarised in an effort to move towards middle-range programme theories that apply across a larger number of engagement strategies or circumstances. During this stage, we may also draw on data from interventions outside CMHC as well as one or several formal, disciplinary theories to help us strengthen our theories of change. Refined programme theories will be discussed and finalised in a participatory manner in one or more meetings with the entire review team.

Discussion and dissemination

Importance of the review

CMHC is a model of care that has garnered worldwide interest as an effective approach to managing common mental disorders in primary care. Recent reviews suggest that implementation of CMHC is underway in North America (US and Canada), Europe (UK, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, Italy), South America and the Caribbean (Chile, Puerto Rico), South Asia (India, Pakistan) and Africa (Uganda).12 13 16 18 As such, CMHC has the potential to impact the lives of millions of people affected by major depression and anxiety disorders. Yet, patients and experts argue that not nearly enough is being done to involve patients and their families in this care,27 54 and engagement of these partners is not yet recognised as a core component of CMHC interventions. Our realist review will address major knowledge gaps in this area and support the design, implementation and evaluation of models of CMHC that consider patients and families as active partners in care.

Involvement of review team members

We are an interdisciplinary, international team of researchers working closely with key knowledge users (KUs) to conduct the realist review and optimise its impacts. Researchers and KUs possess content expertise in several areas relevant to the review, including CMHC, patient and family engagement, interprofessional collaboration and KT. Researchers in the team also possess intimate knowledge of service and policy contexts for three countries that have been primary targets for CMHC implementation (Canada, UK, US). Most researchers in the team have extensive experience in either systematic or realist review methods.

This review will be conducted following an integrated KT approach.55 KUs are full members of the review team and will share their expertise at all stages of the review. They consist of representatives from mental health service user associations, health ministries, a national centre for excellence in mental health, integrated health organisations, a collaborative network for expertise in interprofessional education and practice and a conjoint committee on CMHC of the College of Family Physicians of Canada and Canadian Psychiatric Association. These KUs have already contributed to the preparation of the review by helping to shape our review objectives and scope as well as a funding proposal. In particular, their involvement led to improvements such as an expanded scope to include strategies for family engagement in addition to those aimed solely at patients. As the review progresses, we will rely on them to help us acquire and interpret relevant literature, build and refine our programme theories, disseminate findings and develop effective and tailored KT products.

Two persons with lived experience of depression are core members of our review team. There is limited literature detailing how such individuals can contribute to realist review processes, and so our review will advance knowledge on this topic.56 One of these partners has extensive knowledge and experience delivering peer support services and will be instrumental to our theoretical and practical understanding of these strategies. We expect these partners to contribute in an important way to building and refinement of programme theories for the different patient and family engagement strategies. As recommended by the RAMESES group, initial theory building can sometimes work best by first identifying key outcomes of interest and then working ‘backwards’ and ‘outwards’ to retrieve information on the mechanisms and contextual influences tied to those outcomes.31 In a meeting with our partners with lived experience of depression, we will select outcomes to focus on from among the range of outcomes we will be extracting data on (see the ‘Data extraction and analysis’ section for review part 1). These selections will be shared and discussed with the larger research team, and a final decision on outcomes to focus on will be made. Partners with lived experience will also help us make sense of why certain mechanisms may or may not be triggered under different circumstances. They will play an integral role in the interpretation of emerging results and also provide mentorship to review authors on how they can most meaningfully engaged in the research process. A process evaluation will help us document their involvement in the review, as well as those of our other review team members, in order to make adjustments to our procedures as necessary.

Project outputs

Realist reviews aim to generate context-sensitive explanations about how complex interventions work in order to inform practice and policy.29 With multiple stakeholders involved in our research process, we will aim to improve our understanding of how and why patient and family engagement strategies work in the context of CMHC. This will help us develop guidance for these stakeholders in the form of tailored recommendations and practical advice that KUs can use to inform service planning and policy related to patient and family engagement in CMHC. For healthcare providers, this guidance will be packaged in the form of training materials such as webinars, an implementation guide and a training video. For health administrators and policymakers, we will produce policy briefs57 that summarise what is known and unknown about patient and family engagement in CMHC. Our partners with lived experience will also help us craft plain-language summaries of the evidence to communicate to various mental health associations and networks. Finally, our review findings will be the focus of publications in open-access, peer-reviewed journals and inform research into new models of CMHC with enhanced involvement of patients and their families in the delivery and planning of their primary mental healthcare.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank William Witteman for developing the initial search strategy for this review.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Neasa Martin at @neasa_martin, Matthew Menear at @mattmenear, and France Légaré at @SDM_ULAVAL.

Contributors: MM conceived the study and designed the review with input from EC, M-CC, MJD, M-PG, MG, DH, JH, DN, PP, ES and FL. MM drafted the manuscript. All authors read, critically revised and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work is funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) grant number 201505KRS-350972-KRS-CFBA. The first author is funded by a CIHR Fellowship Award.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J et al. . Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013;382:1575–86. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.deGruy FV. Mental health care in the primary care setting. In: Donaldson MS, Yordy KD, Lohr KN et al., eds. Primary care: America's health in a new era. Washington: (DC: ): National Academy Press, 1996:285–311. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lesage A, Vasiliadis HM, Gagné MA et al. . Prevalence of mental illnesses and related service utilization in Canada: an analysis of the Canadian Community Health Survey. Mississauga: (ON: ): Canadian Collaborative Mental Health Initiative, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization and World Organization of Family Doctors (WONCA). Integrating mental health into primary care: a global perspective. Geneva: WHO, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lecrubier Y. Widespread underrecognition and undertreatment of anxiety and mood disorders: results from 3 European studies. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68(Suppl 2):36–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell AJ, Vaze A, Rao S. Clinical diagnosis of depression in primary care: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2009;374:609–19. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60879-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duhoux A, Fournier L, Menear M. Quality indicators for depression treatment in primary care: a systematic literature review. Curr Psychiat Rev 2011;7:104–37. 10.2174/157340011796391166 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stein MB, Roy-Byrne PP, Craske MG et al. . Quality of and patient satisfaction with primary health care for anxiety disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 2011;72:970–6. 10.4088/JCP.09m05626blu [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberge P, Fournier L, Menear M et al. . Access to psychotherapy for primary care patients with anxiety disorders. Can Psychol 2014;55:60–7. 10.1037/a0036317 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kates N, Mazowita G, Lemire F et al. . The evolution of collaborative mental health care in Canada: a shared vision for the future. Can J Psychiatry 2011;56:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katon W, Unützer J, Wells K et al. . Collaborative depression care: history, evolution and ways to enhance dissemination and sustainability. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2010;32:456–64. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farooq S. Collaborative care for depression: a literature review and a model for implementation in developing countries. Int Health 2013;5:24–8. 10.1093/inthealth/ihs015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sighinolfi C, Nespeca C, Menchetti M et al. . Collaborative care for depression in European countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res 2014;77:247–63. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katzelnick DJ, Williams MD. Large-scale dissemination of collaborative care and implications for psychiatry. Psychiatr Serv 2015;66:904–6. 10.1176/appi.ps.201400529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bower P, Gilbody S, Richards D et al. . Collaborative care for depression in primary care. Making sense of a complex intervention: systematic review and meta-regression. Br J Psychiatry 2006;189:484–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S et al. . Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;10:CD006525 10.1002/14651858.CD006525.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thota AB, Sipe TA, Byard GJ et al. . Collaborative care to improve the management of depressive disorders: a community guide systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med 2012;42:525–38. 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coventry PA, Hudson JL, Kontopantelis E et al. . Characteristics of effective collaborative care for treatment of depression: a systematic review and meta-regression of 74 randomised controlled trials. PLoS One 2014;9:e108114 10.1371/journal.pone.0108114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ekers D, Murphy R, Archer J et al. . Nurse-delivered collaborative care for depression and long-term physical conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2013;149:14–22. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.02.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamann J, Neuner B, Kasper J et al. . Participation preferences of patients with acute and chronic conditions. Health Expect 2007;10:358–63. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2007.00458.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lavoie-Tremblay M, Bonin JP, Bonneville-Roussy A et al. . Families’ and decision makers’ experiences with mental health care reform: the challenge of collaboration. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2012;26:e41–50. 10.1016/j.apnu.2012.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crawford MJ, Rutter D, Manley C et al. . Systematic review of involving patients in the planning and development of health care. BMJ 2002;325:1263 10.1136/bmj.325.7375.1263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel SR, Bakken S, Ruland C. Recent advances in shared decision making for mental health. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2008;21:606–12. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32830eb6b4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Storm M, Edwards A. Models of user involvement in the mental health context: intentions and implementation challenges. Psychiatr Q 2013;84:313–27. 10.1007/s11126-012-9247-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Semrau M, Lempp H, Keynejad R et al. . Service user and caregiver involvement in mental health system strengthening in low- and middle-income countries: systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:79 10.1186/s12913-016-1323-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Panel IECE. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: report of an expert panel. Washington: (DC: ): Interprofessional Education Collaborative, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whyte JM. Consumer commentary special issue: collaborative care. Can J Commun Ment Health 2008;27:11–14. 10.7870/cjcmh-2008-0013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Craven MA, Bland R. Better practices in collaborative mental health care: an analysis of the evidence base. Can J Psychiatry 2006;51(6 Suppl 1):7S–72S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pawson R. Evidence-based policy: a realist perspective. London: Sage Publications, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G et al. . Realist review—a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10(Suppl 1):21–34. 10.1258/1355819054308530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wong G, Westhrop G, Pawson R et al. . Realist synthesis: RAMESES training materials. London: University of London, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al. . The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:W65–94. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G et al. . RAMESES publication standards: realist syntheses. BMC Med 2013;11:21 10.1186/1741-7015-11-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coulter A, Ellins J. Effectiveness of strategies for informing, educating, and involving patients. BMJ 2007;335:24–7. 10.1136/bmj.39246.581169.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M et al. . Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:223–31. 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE et al. . Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 2009;4:50 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R et al. . Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health 2011;38:65–76. 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne AC. Chapter 8: assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions v510. Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. http://handbook.cochrane.org [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huffman JC, Niazi SK, Rundell JR et al. . Essential articles on collaborative care models for the treatment of psychiatric disorders in medical settings: a publication by the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine Research and Evidence-Based Practice Committee. Psychosomatics 2014;55:109–22. 10.1016/j.psym.2013.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Booth A, Carroll C. Systematic searching for theory to inform systematic reviews: is it feasible? Health Info Libr J 2015;32:220–35. 10.1111/hir.12108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pfeiffer PN, Heisler M, Piette JD et al. . Efficacy of peer support interventions for depression: a meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2011;33:29–36. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Houle J, Gascon-Depatie M, Bélanger-Dumontier G et al. . Depression self-management support: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 2013;91:271–9. 10.1016/j.pec.2013.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Légaré F, Stacey D, Turcotte S et al. . Interventions for improving the adoption of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;(9):CD006732 10.1002/14651858.CD006732.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bee P, Price O, Baker J et al. . Systematic synthesis of barriers and facilitators to service user-led care planning. Br J Psychiatry 2015;207:104–14. 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.152447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kastner M, Makarski J, Hayden L et al. . Making sense of complex data: a mapping process for analyzing findings of a realist review on guideline implementability. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:112 10.1186/1471-2288-13-112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Booth A, Harris J, Croot E et al. . Towards a methodology for cluster searching to provide conceptual and contextual “richness” for systematic reviews of complex interventions: case study (CLUSTER). BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:118 10.1186/1471-2288-13-118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pace R, Pluye P, Bartlett G et al. . Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies reviews. Int J Nurs Stud 2012;49:47–53. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I et al. . Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014;348:g1687 10.1136/bmj.g1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meyer SB, Lunnay B. The application of abductive and retroductive inferences for the design and analysis of theory-driven sociological research. Sociol Res Online 2013;18:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dalkin SM, Greenhalgh J, Jones D et al. . What's in a mechanism? Development of a key concept in realist evaluation. Implement Sci 2015;10:49 10.1186/s13012-015-0237-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Pawson R. Internet-based medical education: a realist review of what works, for whom and in what circumstances. BMC Med Educ 2010;10:12 10.1186/1472-6920-10-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wong G, Pawson R, Owen L. Policy guidance on threats to legislative interventions in public health: a realist synthesis. BMC Public Health 2011;11:222 10.1186/1471-2458-11-222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thomas DR, Thomas YL. Interventions to reduce injuries when transferring patients: a critical appraisal of reviews and a realist synthesis. Int J Nurs Stud 2014;51:1381–94. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kates N, Gagné MA, Whyte JM. Collaborative mental health care in Canada: looking back and looking ahead. Can J Commun Mental Health 2008;27:1–4. 10.7870/cjcmh-2008-0011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Research CIoH. Guide to knowledge translation planning at CIHR: integrated and end-of-grant approaches. Ottawa: CIHR, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harris J, Croot L, Thompson J et al. . How stakeholder participation can contribute to systematic reviews of complex interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health 2016;70:207–14. 10.1136/jech-2015-205701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lavis JN, Permanand G, Oxman AD et al. . SUPPORT Tools for evidence-informed health Policymaking (STP) 13: preparing and using policy briefs to support evidence-informed policymaking. Health Res Policy Syst 2009;7(Suppl 1):S13 10.1186/1478-4505-7-S1-S13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-012949supp_appendix.pdf (89.8KB, pdf)