Abstract

In using a patient-centered approach, neither a clinician nor a prognostic score can predict with absolute certainty how well a patient will do or how long he will live; however, validated prognostic scores may improve accuracy of prognostic estimates, thereby enhancing the ability of the clinicians to appreciate the individual burden of disease and the prognosis of their patients and inform them accordingly. They may also facilitate nephrologist’s recommendation of dialysis services to those who may benefit and proposal of alternative care pathways that might better respect patients’ values and goals to those who are unlikely to benefit. The purpose of this article is to discuss the use as well as the limits and deficiencies of currently available prognostic tools. It will describe new predictors that could be integrated in future scores and the role of patients’ priorities in development of new scores. Delivering patient-centered care requires an understanding of patients’ priorities that are important and relevant to them. Because of limits of available scores, the contribution of new prognostic tools with specific markers of the trajectories for patients with CKD and patients’ health reports should be evaluated in relation to their transportability to different clinical and cultural contexts and their potential for integration into the decision-making processes. The benefit of their use then needs to be quantified in clinical practice by outcome studies including health–related quality of life, patient and caregiver satisfaction, or utility for improving clinical management pathways and tailoring individualized patient–centered strategies of care. Future research also needs to incorporate qualitative methods involving patients and their caregivers to better understand the barriers and facilitators to use of these tools in the clinical setting. Information given to patients should be supported by a more realistic approach to what dialysis is likely to entail for the individual patient in terms of likely quality and quantity of life according to the patient’s values and goals and not just the possibility of life prolongation.

Keywords: supportive care, chronic kidney disease, survival, Epidemiology and outcomes, Caregivers, Decision Making, Humans, Patient-Centered Care, Personal Satisfaction, Prognosis, quality of life, renal dialysis

Introduction

Patients with CKD are a vulnerable population with high morbidity and mortality, and they presently have significant unmet supportive care needs (1). The prevalence of symptoms, like pain, fatigue, anorexia, and dyspnea, as well as geriatric syndromes, such as dementia and frailty, is high, and symptoms have an important effect on quality of life (2,3). Other than mortality and comorbidities that are usually documented in medical records, clinical studies, or registries, additional information that is highly relevant to patients, such as symptom burden or health–related quality of life (HRQOL), could be provided through Patient-Centered Assessments (3). This information may enhance the capability of clinicians to appreciate the individual burden of disease and the prognosis of their patients and adapt their care accordingly.

CKD is a chronic disease that may span many years. During this period, many clinical decisions may need to be considered, such as whether to initiate RRT (4), considering dialysis withdrawal, integrating supportive care, or organizing end of life support. All of these decisions should integrate the patient and family perspective in a process of informed consent. Valuable information on prognosis will spur the exchange between health professionals and patients, taking into account that many individual or cultural aspects will influence the shared decision–making process, in which practitioners and patients jointly consider best clinical evidence in light of a patient’s specific health characteristics and values when choosing health care (5,6).

Although neither a clinician nor a prognostic score can predict with absolute certainty how well a patient will do or how long he/she will live, validated prognostic scores may improve the accuracy of the prognostic estimates that influence the clinical decisions and a patient-centered approach (7). As well, in the evaluation of the advantages for patients and cost-effectiveness of kidney supportive care (8), it is important to take into account the case mix of the patients to be able to compare different organizations, clinical practices, or countries. Therefore, socioeconomic models may be adjusted on the score estimates instead of various comorbidities or other health indicators.

The purpose of this article is to discuss the use as well as the limits and deficiencies of currently available prognostic tools. This article includes discussion of new predictors that could be integrated in future scores and the role of patients priorities in the development of new scores. In this paper, the term score will refer to integrated prognostic scoring systems that incorporate clinical, biologic, and other characteristics into a single risk score. When these scores are used for risk stratification, they will be referred to as prognostic tools.

Why Do We Need New Prognostic Tools?

Usefulness of Prognostic Tools

Prognostic tools provide an estimate of how many people with similar risk factors will experience a given event (for example, death), but they cannot identify who will experience this given event.

The Renal Physician Association (RPA) and the American Society of Nephrology in their clinical practice guideline on shared decision making in the appropriate initiation of and withdrawal from dialysis recommend that “[a]ll patients requiring dialysis should have their chances for survival estimated, with the realization that the ability to predict survival in the individual patient is difficult and imprecise” (9). This patient-specific estimate of prognosis aims to facilitate informed consent in the process of shared decision making and support the discussion of supportive care goals (9). Prognosis of the course of an illness is among the main responsibilities of medical doctors (10). Studies have shown consistently that patients want to have the nephrologist discuss their prognosis but that this is rarely done (11–13). Prognostic tools could help health professionals identify high-risk patients and facilitate discussions regarding adapted care (for example, potential imminent need for supportive care), ethics advice, or treatment adjustment. Overoptimistic estimations of prognosis may lead to inappropriately disease–directed treatment (14,15). Validated prognostic scores may also facilitate nephrologist recommendation of dialysis services to those most likely to benefit and proposal of alternative care pathways that might better respect patients’ values and goals to those unlikely to benefit (16).

Prognostic tools could also help in shared decision making with patients and their loved ones, who have the right to be informed and part of the decision-making process in any decision concerning their treatment. Decision support interventions help people consider the choices that they face, they describe where and why choice exists, and they provide information about options. Prognostic tools would be especially useful when conservative management is discussed in the various following situations: in advanced CKD care with the incorporation of palliative care principles and without the initiation of RRT (17), in palliative dialysis (3), or in dialysis withdrawal (18). Evidence-based information about outcomes improves people’s knowledge regarding options, reduces their decisional conflict related to feeling uninformed and unclear about their personal values, and improves accurate risk perceptions when probabilities are included (19). Especially in older adults, information about prognosis may help patients plan for their remaining lifetime.

Current Tools Available

In the past, prognosis was primarily guided by clinical acumen. Later, ancillary information, such as laboratory data and imaging studies, was added. Over the years, the sheer amount of information related to the patient and his/her likely trajectory became vast, and systematic approaches to integration of data from multiple sources became a necessity. Although this patient population has frequent encounters with medical staff, which should, in theory, assist in prognostication (by increasing the clinician estimate of prognostication), the process is hindered by the realities of patient frailty and comorbidities. In the process of shared decision making, gut instinct is usually complemented by an analytic approach, where deliberation of multiple factors takes center stage (incorporating laboratory and demographic data other than the clinician’s estimate). Prognostic scores are meant to support this analytic process.

In the past 10 years, numerous scores of mortality on dialysis have been developed on the basis of various combinations of comorbidities and laboratory data. Although early mortality scores are important to consideration of end of life support or requirement for hospice (4), only a few of them focused on short-term survival (≤6 months) (20–24), some of which included only elderly patients on dialysis (21–23). These prognostic scores are summarized in Table 1. Other factors, like self–rated health question (25), perceived treatment control (26), patients’ illness perception (27), Karnofsky performance score (28), or frailty (29,30), are related to survival, but their prognostic value for short-term mortality (≤6 months) has not yet been evaluated. Other scores were developed to predict progression to kidney failure in patients with CKD stages 3–5, but they usually predict a long-term risk (≥1 year) and may not be directly useful in the context of when to incorporate kidney supportive care (31–33).

Table 1.

Current tools available to predict short-term mortality on dialysis and need of kidney supportive care

| Source | Population Studied | Parameter | c Statistic | Reference |

| 3-mo Survival after dialysis start | ||||

| US Renal Data System | 69,441 incident patients aged ≥67 yr old | Age, albumin, assistance with activities of daily living, nursing home, cancer, heart failure, and hospitalization | 0.68 | Thamer et al. (23) |

| A more comprehensive version adds sex, race, central vein dialysis catheter use, early nephrology referral, albumin, creatinine, peripheral vascular disease, and alcohol abuse | 0.71 | |||

| French REIN registry | 28,496 incident patients aged ≥75 yr old | Sex, age, congestive heart failure, severe peripheral vascular disease, dysrhythmia, severe behavioral disorders, active malignancy, serum albumin, and impaired mobility | 0.75 (95% CI, 0.74 to 0.76) | Couchoud et al. (21) |

| Catalan renal registry | 1365 incident adult patients with diabetes | Age, functional autonomy, heart disease, and central catheter as vascular access | 0.77 | Mauri et al. (20) |

| 6-mo Survival after dialysis start | ||||

| French REIN registry | 4142 incident patients aged ≥75 yr old | BMI, diabetes, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, dysrhythmia, active malignancy, severe behavioral disorder, dependency for transfers, and initial context of dialysis start | 0.70 | Couchoud et al. (22) |

| 6-mo Survival on HD | ||||

| New England HD clinics | 1026 adult patients on maintenance HD | Age, dementia, peripheral vascular disease, serum albumin, and the surprise question | 0.80 (95% CI, 0.73 to 0.88) | Cohen et al. (24) |

REIN, Renal Epidemiology and Information Network; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; HD, hemodialysis.

“The use of objective measurable data in statistical predictions is more accurate than the subjective impressions or intuitions or clinical judgment of trained professionals” (Daniel Kahneman, Nobel Prize winner). However, clinical intuition may add value when two basic conditions are met: an environment sufficiently regular to be predictable and an opportunity to learn these regularities through prolonged practice (34). An example is given by the integration of the surprise question in a score that also includes objective measures (24). The discrimination value of this score developed by Cohen et al. (24) is higher than other scores, although predictive power varies with clinical discipline, seniority, and clinical setting (35).

Use of Prognostic Tools in Daily Practice

Although for individual patients, current prognostic tools are not sensitive or specific enough to tell a patient how long they will live, they are informative at identifying high-risk populations. This group of patients can then be targeted for specific interventions that can potentially benefit them. The prognostic tools can also be used alongside decision aids to help in the shared decision–making process for individual patients (36).

Multivariate predictive scores provide death probabilities and probability cutoffs that can be chosen as relevant for a given clinical context (e.g., predictions for considering a more palliative approach to care versus predictions that would suggest that patients may have a higher likelihood of benefitting from various life–prolonging interventions). They can be automated, and their administration does not have to consume additional physician time (except the surprise question). Currently, these tools are available for free online (https://qxmd.com/calculate/3-month-mortality-in-incident-elderly-esrd-patients) and also, on mobile applications (calculated by QxMD). They also can be used along with the RPA Shared Decision Making toolkit (https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/rpa-sdm-toolkit/id843971920?mt=8). Figure 1 illustrates how a prognostic tool can be incorporated into a decision process for kidney supportive care.

Figure 1.

Role of the prognostic tool in kidney supportive care decision. *Search for geriatric syndromes (such as dementia, functional disability, malnutrition or depression) and assessment of patients' psychosocial and spiritual situations.

There is early experience with the use of prognostic tools in kidney programs, especially in the United Kingdom and Canada, where these tools are being used primarily to help identify high-risk patients for additional supportive care. However, a recent national survey of Canadian nephrologists showed that >80% of the respondents were not satisfied with their current ability to predict clinical trajectories and that this ability was perceived to be very important for decision making. Furthermore, there was strong support for the further development and uptake of validated prognostic tools to enhance appropriate care that is aligned with patients’ priorities and illness trajectory (37).

Limitations or Deficiencies of the Current Tools

The process of prognostication is difficult and complex because of patients’ multiple comorbidities and overlap of different prognoses. The global health of patients with CKD includes many domains, like comorbidities as well as functional impairment, geriatric syndromes, and social environment. All of these domains have to be taken into account because of their potential effect on outcome and quality of life. Therefore, new prognostic scores that integrate these domains need to be developed.

Recent work has identified that enhanced communication among patients and providers, especially around dialysis modality options, is a top Canadian patient priority (38). This will require a better understanding of illness trajectories, focusing on not just survival but also, other outcomes equally relevant to patients, such as the effect of treatments on HRQOL and physical function, hospital-free survival, place of death, and capabilities (8). In fact, current predictive tools are not necessarily patient focused and do not necessarily address their concerns or their family concerns. Clinicians should be trained to better communicate prognosis in particular by tailoring the conversation to the individual patient’s preferences for information and participation in the informed consent process (5,6). For patients with complex cases, a specialist palliative care consultation can be very valuable to organize and support this prognosis communication. The access to outpatient specialist palliative care, limited in many countries, should be improved.

To help the integration of those tools into clinical practice, it is important to clarify when those scores should be used, which score should be used in which context, how these estimates should be communicated to the patients, and how they can be integrated in a shared decision–making process. For example, we recently proposed a risk stratification algorithm to screen for evaluation, evaluate, and decide on an appropriate strategy of care for elderly patients with ESRD according to their level of risk of early death (21). Such an approach illustrates the usefulness of prognostic tools to decide the right timing of starting kidney supportive care.

Potential New Predictors That Could Be Integrated into New Prognostic Tools for Mortality

Because of the limits of available scores to accurately predict the outcomes of patients, the contributions of new markers should be evaluated.

Sentinel Events and Biomarkers in Patients on Dialysis

Recent research has indicated that death in patients on dialysis is preceded by characteristic events, such as hospitalizations (39) or a decline in HRQOL scores (S. Johnstone, et al., unpublished data). The dynamics of laboratory and clinical changes seem to accelerate in the terminal 6 months before death as shown by analysis of their rates of change (Table 2). Decrease in albumin level (40,41), BP (41), and body temperature (42) on the one hand and increase in glucose (Calice-Silva, et al., unpublished data), C–reactive protein levels (41), and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (43) on the other hand are associated with an increased risk of death. In addition, a reduced nutritional score (44) and worsened nutritional competence as indicated by lower body weight (40,45), interdialytic weight gain (41,43), phosphorus (43), lean body mass, and fat mass on one hand and increased fluid overload (A. Guinsburg, et al., unpublished data) on the other hand are also associated with an increased risk of death. Increased inflammation and poor nutrition translate into distinct alterations in body composition, with a loss of lean body mass and fat mass. Although the pathologic pathways underlying these sentinel events remain to be determined, it seems that a surge of inflammation may provide a reasonable unifying concept (41).

Table 2.

Potential new predictors to be integrated in prognostic scores because of their dynamics in the terminal months

| Parameter | Population Studied | Dynamics in Terminal Months before Death | References |

| Body composition | |||

| Body weight (post-HD) | Women and men from the United States (blacks, whites, and Hispanics) | Decline at a rate of ≤3.2 kg per quarter | Kotanko et al. (40,45) |

| Body mass index | Women and men patients on PD from Brazil | Decline at a rate of ≤0.23 kg/m2 per quarter | Calice-Silva, et al., unpublished data |

| Fat mass | Women and men from Europe, South America, and Asia | Decline by 1.4 kg from months 9–12 to months 1–3 before death | A. Guinsburg, et al., unpublished data |

| Fluid overload, L | Women and men from Europe, South America, and Asia | Increase by 0.3 L from months 9–12 to months 1–3 before death | A. Guinsburg, et al., unpublished data |

| Fluid overload, % of lean tissue and fat mass | Women and men from Europe, South America, and Asia | Increase by 0.8% points from months 9–12 to months 1–3 before death | A. Guinsburg, et al., unpublished data |

| Lean body mass | Women and men from Europe, South America, and Asia | Decline by 0.8 kg from months 9–12 to months 1–3 before death | A. Guinsburg, et al., unpublished data |

| Clinical indicator | |||

| BP (pre–HD systolic BP) | Women and men from the Americas (blacks, whites, and Hispanics), Europe, and Asia | Decline at a rate of ≤8 mmHg per quarter | Usvyat et al. (41) |

| Hospitalization | Women and men from the United States (blacks, whites, and Hispanics) | Increase from 0.32 ppm 4 mo before death to 1.85 ppm in month of death | Usvyat et al. (39) |

| IDWG, kg | Women and men from the Americas (blacks, whites, and Hispanics), Europe, and Asia | Decline at a rate of ≤0.15 kg per quarter | Usvyat et al. (43) |

| IDWG, % of post-HD weight | Women and men from the Americas (blacks, whites, and Hispanics), Europe, and Asia | Decline at a rate of ≤0.3% per quarter | Usvyat et al. (41) |

| Temperature (pre-HD) | Women and men from the United States (blacks, whites, and Hispanics) | Decline at a rate of ≤0.19°C per quarter | Usvyat et al. (42) |

| Laboratory indicator | |||

| Albumin | Women and men from the Americas (blacks, whites, and Hispanics), Europe, and Asia | Decline at a rate of ≥0.5 g/dl per quarter | Kotanko et al. (40), Usvyat et al. (41) |

| C-reactive protein | Women and men from Europe | Increase at a rate of ≥20 mg/L per quarter | Usvyat et al. (41) |

| Glucose | Women and men patients on PD from Brazil | Increase at a rate of ≥5 mg/dl per quarter | Calice-Silva et al., unpublished data |

| Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio | Women and men from the Americas (blacks, whites, and Hispanics), Europe, Asia | Increase at a rate of ≥2.0 U per quarter | Usvyat et al. (43) |

| Nutritional score (composite of albumin, phosphate, creatinine, enPCR, and IDWG) | Women and men from the United States (blacks, whites, and Hispanics) | Decline at a rate of ≥3.0 percentile points per quarter | Thijssen et al. (44) |

| Potassium | Women and men patients on PD from Brazil | Decline at a rate of ≥0.05 mmol/L per quarter | Calice-Silva et al. (76) |

| Phosphorus | Women and men from the Americas (blacks, whites, and Hispanics), Europe, and Asia | Decline at a rate of ≥0.2 mg/dl per quarter | Usvyat et al. (43) |

| Quality of life | |||

| SF-36 Physical Component Score | Women and men from the United States (blacks, whites, and Hispanics) | Decline at a rate of ≥0.29 points per quarter | S. Johnstone, et al., unpublished data |

| SF-36 Mental Component Score | Women and men from the United States (blacks, whites, and Hispanics) | Decline at a rate of ≥0.49 points per quarter | S. Johnstone, et al., unpublished data |

| Karnofsky Index | Women and men patients on PD from Brazil | Decline at a rate of ≥5.9 points per quarter | A. Modesto, et al., unpublished data |

HD, hemodialysis; PD, peritoneal dialysis; ppm, per patient-month; IWDG, interdialytic weight gain; enPCR, equilibrated normalized protein catabolic rate; SF-36, Short Form (36) Health Survey.

Lessons from Other Populations

Numerous scores have been developed in populations other than patients with CKD. These scores typically use a combination of symptoms, syndromes, or functional measures that could be relevant for patients with CKD. Future research needs to focus on creating more robust models that look at these additional variables and evaluate their performance in patients with CKD.

In the general population, the Patient–Reported Outcome Mortality Prediction Tool, which assesses sociodemographic characteristics, health and lifestyle behaviors, comorbidities, activities of daily living, and HRQOL, is a promising tool to predict 6-month mortality in elderly patients (46). In patients with cancer, low performance status or its deterioration (47,48) and the Clinical Prediction of Survival (15,47,49,50) are associated with short-term mortality. Numerous scores with good discrimination performance have been developed in the context of palliative care. They include a combination of the following factors: Karnofsky performance scale, ambulation, activity, evidence of disease, self-care, oral intake, edema, dyspnea at rest, delirium, level of consciousness, clinical prediction of survival, total white blood cell count, and lymphocyte percentage (47,48,51).

Where Do We Need to Go with New Prognostic Tools Other Than Mortality?

Patients’ Priorities

Patient-centered care involves shared decision making and disease management between a patient and his/her clinician. A shared decision–making process can ultimately encourage adherence to treatment and improve patient-centered outcomes (52). Delivering patient-centered care requires an understanding of outcomes that are important and relevant to patients. However, the CKD research agenda has been driven traditionally by investigators, resulting in studies that may not optimally inform patient care or may not show priorities for those who are affected by the condition (53,54). The importance of engaging the broader stakeholder community, including patients and their caregivers, in determining research priorities and actively participating in the research has been recognized. Risk of hospitalization, HRQOL, cost, and intercurrent events may be other priorities to the patients in addition to survival (8). A recent systematic review (55) of research priority setting in kidney disease identified 16 studies that elicited patient, caregiver, or health care provider priorities for research in kidney disease; of those, only four (25%) explicitly involved patients, and only one included patients with early stages of CKD not yet on dialysis. For example, a recent study has shown that patients tend to prioritize outcomes that are more relevant to their daily living and wellbeing, like ability to work, whereas caregivers ranked mortality, anxiety, and depression higher than patients did (56).

Despite efforts to increase patient involvement in research for more than a decade, there has been little progress (57), and recent studies continue to identify a lack of patient engagement in the research priority setting (58). More recently, steps have been taken to ensure patient engagement in research and the research priority setting, with funding agencies in several countries now mandating patient engagement as a requirement for funding consideration: the Patient–Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI; http://www.pcori.org/research-we-support/pcor/) in the United States, the INVOLVE Project (http://www.invo.org.uk/about-involve/) in the United Kingdom, and the Strategy for Patient Oriented Research (http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/41204.html) in Canada. For example, the PCORI is supporting research of a peer–led mentoring program and home-based care, whereas the INVOLVE Project supported research on a self-management intervention and the effect of social media.

Predictors of Quality of Life, Hospitalization, and Functional Decline

Frailty affects both physical and mental quality of life in predialysis patients with CKD (59,60). Frailty measured with five components (shrinking, weakness, exhaustion, low activity, and slowed walking speed) is an independent predictor of number of hospitalizations (61). Gait speed is a predictor of hospitalization and functional decline (difficulty with activities of daily living and estimated change in Short Form [36] Health Survey Physical Function score) at 12 months in prevalent patients on hemodialysis (62). Self-reported appetite is significantly associated with several measures of inflammatory and nutritional status, and poor appetite is associated to lower subjective HRQOL and increased rates of hospitalization and mortality during a 12-month follow-up period (63). The contribution of those predictors in prognosis score should now be evaluated.

In other populations, weight loss, fatigue, and markers of systemic inflammation are associated with adverse HRQOL, reduced functional abilities, more symptoms, and shorter survival (64). In particular, fatigue is a common symptom associated with the presence of inflammation, poor quality of sleep, depression, anxiety, and poor HRQOL (65). Physical frailty indicators can predict disability in activities of daily living in community–dwelling elderly people (66). The screening tool Identification of Seniors at Risk–Primary Care has moderate predictive value in identifying persons at increased risk of functional decline in community-dwelling persons aged ≥70 years old (69) or elderly patients presenting to an emergency department (68,69).

Ethical Aspects

To ensure that patients are not unfairly discriminated against, prognostic tools should not be used (1) to deny a treatment, (2) across populations without consideration of context, (3) beyond the boundaries of the derivation or validation cohort without recognition of limitations, (4) without appreciation of the uncertainty of the estimates of prognosis, (5) to irreversibly classify or categorize a patient without appreciation of the possibility of a change in status, and finally, (6) in isolation without considerations of clinical context.

Evaluation of New Prognostic Tools

Generalizability

No matter how well calibrated and discriminating (Figures 2 and 3) a prognostic tool may be in development, a tool that can only predict outcomes in the sample in which it was developed is useless. For a system to be generalizable, the accuracy of the tool must be both reproducible (accurate in an identical population) and transportable (70). Transportability is shown if the system is accurate in patients drawn from a different but related population or data collected by using methods that differ from those used in development. Historical and geographic accuracy is maintained when the system is tested on data from different calendar times or different locations. Methodologic accuracy is maintained when the system is tested on data collected by using different methods. Spectrum accuracy is maintained in a patient sample that is, on average, more or less advanced in disease process or that has a somewhat different disease process or trajectory. Follow-up interval accuracy is maintained when the system is tested over a longer or shorter period.

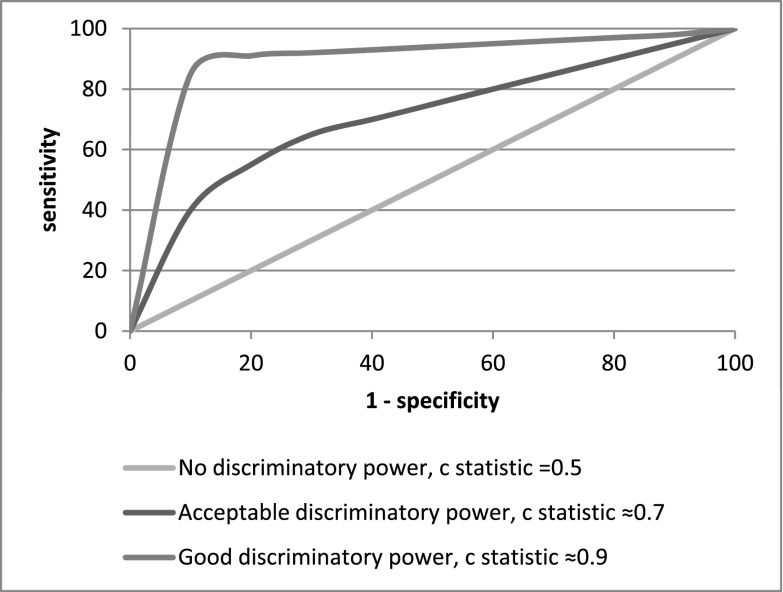

Figure 2.

Examples of receiver operating characteristic curves. Discrimination is the ability of the score to distinguish high-risk subjects from low-risk subjects. In the context of survival, it is usually assessed by Harrell c statistic, which is an extension of the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve. The c statistic is equal to the probability that a score will rank a high-risk subject higher than a low-risk subject. When the c statistic is >0.7, the score has acceptable discriminatory power. When the c statistic is equal to 0.5, the score has the same power as flipping a coin.

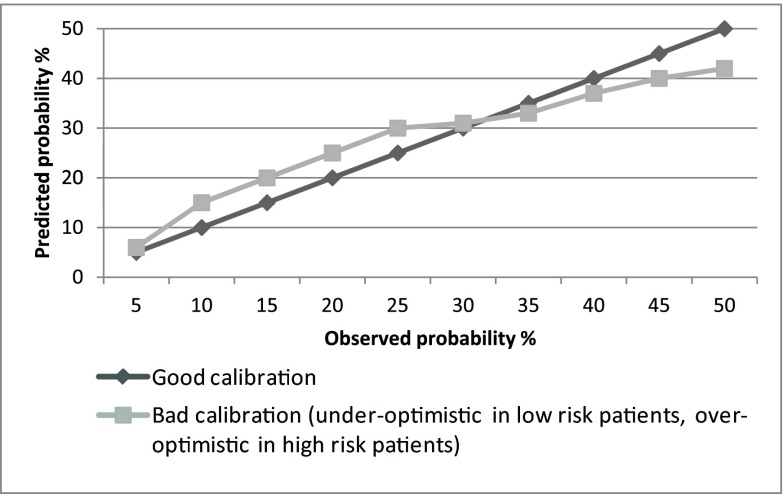

Figure 3.

Examples of calibration curves. The calibration curve compares the predicted and observed probabilities of the event in different subgroups at risk (score strata). The global calibration performance can be tested with the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness of fit test. A P value >0.05 suggests that the score is accurate on the whole.

Effect

After a tool has been developed with specific interventions and its accuracy and transportability have been assessed, one should evaluate how the utilization of this tool will affect clinical decision making and the care of patients (16). In other words, the tool has to be integrated into decision-making processes, and its benefit on health outcomes (such as HRQOL), patient satisfaction, and processes of care (such as improving clinical management pathways and tailoring individualized patient–centered strategies of care) must be shown.

Various epidemiologic intervention methodologies can be used, like cluster randomized, controlled trials (71–73) or controlled before-after studies. Advantages of cluster randomized, controlled trials over individually randomized, controlled trials include the ability to control for contamination across individuals, especially in studies that evaluate global strategies and not a specific intervention.

Dissemination

A dissemination strategy is a systematic plan for ensuring the dissemination of the prognostic tool to key internal and external stakeholders through diverse, effective, creative, and barrier-free methods after the tool has been finalized. The aim of the strategy is to ensure effective communication and dissemination of the prognostic tool to stakeholders to maximize use. Effect studies and tailored interventions can help this dissemination (74).

Figure 4 illustrates a framework for development of a new tool.

Figure 4.

Framework for development of a new tool.

Research Perspectives

Developing accurate and pertinent scores is the first step. Nephrology researchers now have to move on to transform these scores into tools that are useful for decision making in clinical practice. The effect of the use of prognosis tools on key health issues for patients with CKD must take the form of tangible research programs. Such effect studies may also help nephrologists to choose a prognostic tool for their particular patient given the many studies that exist.

The Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes Controversies Conference on Supportive Care (7) recently recommended that methods of communicating prognosis and integrating the biomedical facts of prognosis with the emotional, social, and spiritual realities of the patient should be developed and evaluated along with research into methods of how to communicate the uncertainty (75) of predicting outcomes and individual patient trajectories.

Future research also needs to incorporate qualitative research involving patients and their caregivers to better identify improvement of prognostic tools and evaluate their use in different clinical and cultural contexts (5). Information given to the patients should be supported by a more realistic approach to what dialysis is likely to entail for the individual patient in terms of likely quality and quantity of life according to the patient’s values and goals and not just the possibility of life prolongation. Therefore, future prognostic scores should focus on other outcomes relevant to the patients (3,8). However, prognostication in survival is still a challenge, and the contributions of new predictors, either specifics markers of the trajectories of patients with CKD or patients’ perceived health reports, should be considered.

Conclusions

Prediction scores aim to provide accurate information to patients, especially in advanced illness, where the balance between quantitative and qualitative gain in outcome may be discussed (4). Sentinel events, biomarkers, and patients’ health reports may enhance the accuracy of current scores, which are largely on the basis of comorbidities. However, the implementation and the effect of scores in shared decision–making processes have to be evaluated in different clinical and cultural contexts (5). Also, there is an urgent need to shift our prediction goal from survival to outcomes equally relevant to patients, like HRQOL (3,8). These tools may enhance the ability of clinicians to advise their patients according to their prognosis, facilitate informed consent in the process of shared decision making, and support the discussion of the patients’ goals of care.

Disclosures

None.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Culp S, Lupu D, Arenella C, Armistead N, Moss AH: Unmet supportive care needs in U.S. dialysis centers and lack of knowledge of available resources to address them. J Pain Symptom Manage 51: 756–761.e2, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moens K, Higginson IJ, Harding R; EURO IMPACT: Are there differences in the prevalence of palliative care-related problems in people living with advanced cancer and eight non-cancer conditions? A systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 48: 660–677, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davison SN, Jassal SV: Supportive care: Integration of patient-centered kidney care to manage symptoms and geriatric syndromes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1879–1880, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown EA, Bekker HL, Davison SN, Koffman J, Schell JO: Supportive care: Communication strategies to improve cultural competence in shared decision making. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1902–1908, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murtagh FEM, Burns A, Moranne O, Morton RL, Naicker S: Supportive care: Comprehensive conservative care in end-stage kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1909–1914, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michel DM, Moss AH: Communicating prognosis in the dialysis consent process: A patient-centered, guideline-supported approach. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 12: 196–201, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davison SN, Levin A, Moss AH, Jha V, Brown EA, Brennan F, Murtagh FE, Naicker S, Germain MJ, O'Donoghue DJ, Morton RL, Obrador GT: Executive summary of the KDIGO Controversies Conference on Supportive Care in Chronic Kidney Disease: Developing a roadmap to improving quality care. Kidney Int 88: 447–459, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morton RL, Tamura MK, Coast J, Davison SN: Supportive care: Economic considerations in advanced kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1915–1920, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moss AH: Shared decision-making in dialysis: The new RPA/ASN guideline on appropriate initiation and withdrawal of treatment. Am J Kidney Dis 37: 1081–1091, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christakis NA: Death Foretold: Prophecy and Prognosis in Medical Care, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1999

- 11.Davison SN: End-of-life care preferences and needs: Perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 195–204, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davison SN, Jhangri GS, Holley JL, Moss AH: Nephrologists’ reported preparedness for end-of-life decision-making. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 1256–1262, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schell JO, Green JA, Tulsky JA, Arnold RM: Communication skills training for dialysis decision-making and end-of-life care in nephrology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 675–680, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheon S, Agarwal A, Popovic M, Milakovic M, Lam M, Fu W, DiGiovanni J, Lam H, Lechner B, Pulenzas N, Chow R, Chow E: The accuracy of clinicians’ predictions of survival in advanced cancer: A review. Ann Palliat Med 5: 22–29, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glare P, Virik K, Jones M, Hudson M, Eychmuller S, Simes J, Christakis N: A systematic review of physicians’ survival predictions in terminally ill cancer patients. BMJ 327: 195–198, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yourman LC, Lee SJ, Schonberg MA, Widera EW, Smith AK: Prognostic indices for older adults: A systematic review. JAMA 307: 182–192, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Connor NR, Kumar P: Conservative management of end-stage renal disease without dialysis: A systematic review. J Palliat Med 15: 228–235, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt RJ, Moss AH: Dying on dialysis: The case for a dignified withdrawal. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 174–180, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stacey D, Légaré F, Col NF, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, Eden KB, Holmes-Rovner M, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Lyddiatt A, Thomson R, Trevena L, Wu JH: Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1: CD001431, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mauri JM, Vela E, Clèries M: Development of a predictive model for early death in diabetic patients entering hemodialysis: A population-based study. Acta Diabetol 45: 203–209, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Couchoud CG, Beuscart JB, Aldigier JC, Brunet PJ, Moranne OP; REIN registry: Development of a risk stratification algorithm to improve patient-centered care and decision making for incident elderly patients with end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int 88: 1178–1186, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Couchoud C, Labeeuw M, Moranne O, Allot V, Esnault V, Frimat L, Stengel B; French Renal Epidemiology and Information Network (REIN) registry: A clinical score to predict 6-month prognosis in elderly patients starting dialysis for end-stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 1553–1561, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thamer M, Kaufman JS, Zhang Y, Zhang Q, Cotter DJ, Bang H: Predicting early death among elderly dialysis patients: Development and validation of a risk score to assist shared decision making for dialysis initiation. Am J Kidney Dis 66: 1024–1032, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen LM, Ruthazer R, Moss AH, Germain MJ: Predicting six-month mortality for patients who are on maintenance hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 72–79, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thong MS, Kaptein AA, Benyamini Y, Krediet RT, Boeschoten EW, Dekker FW; Netherlands Cooperative Study on the Adequacy of Dialysis (NECOSAD) Study Group: Association between a self-rated health question and mortality in young and old dialysis patients: A cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 52: 111–117, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Dijk S, Scharloo M, Kaptein AA, Thong MS, Boeschoten EW, Grootendorst DC, Krediet RT, Dekker FW, Apperloo AJ, Bijlsma JA, Boekhout M, Boer WH, van der Boog PJ, Büller HR, van Buren M, de Charro FT, Doorenbos CJ, van den Dorpel MA, van Es A, Fagel WJ, Feith GW, de Fijter CW, Frenken LA, van Geelen JA, Gerlag PG, Grave W, Gorgels JP, Huisman RM, Jager KJ, Jie K, Koning-Mulder WA, Koolen MI, Hovinga TK, Lavrijssen AT, Luik AJ, van der Meulen J, Parlevliet KJ, Raasveld MH, van der Sande FM, Schonck MJ, Schuurmans MM, Siegert CE, Stegeman CA, Stevens P, Thijssen JG, Valentijn RM, Vastenburg GH, Verburgh CA, Vincent HH, Vos PF; NECOSAD Study Group: Patients’ representations of their end-stage renal disease: relation with mortality. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 3183–3185, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parfeni M, Nistor I, Covic A: A systematic review regarding the association of illness perception and survival among end-stage renal disease patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 28: 2407–2414, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ritchie JP, Alderson H, Green D, Chiu D, Sinha S, Middleton R, O’Donoghue D, Kalra PA: Functional status and mortality in chronic kidney disease: results from a prospective observational study. Nephron Clin Pract 128: 22–28, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johansen KL, Chertow GM, Jin C, Kutner NG: Significance of frailty among dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2960–2967, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Painter P, Roshanravan B: The association of physical activity and physical function with clinical outcomes in adults with chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 22: 615–623, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tangri N, Stevens LA, Griffith J, Tighiouart H, Djurdjev O, Naimark D, Levin A, Levey AS: A predictive model for progression of chronic kidney disease to kidney failure. JAMA 305: 1553–1559, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drawz PE, Goswami P, Azem R, Babineau DC, Rahman M: A simple tool to predict end-stage renal disease within 1 year in elderly adults with advanced chronic kidney disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 61: 762–768, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tangri N, Grams ME, Levey AS, Coresh J, Appel LJ, Astor BC, Chodick G, Collins AJ, Djurdjev O, Elley CR, Evans M, Garg AX, Hallan SI, Inker LA, Ito S, Jee SH, Kovesdy CP, Kronenberg F, Heerspink HJ, Marks A, Nadkarni GN, Navaneethan SD, Nelson RG, Titze S, Sarnak MJ, Stengel B, Woodward M, Iseki K; CKD Prognosis Consortium: Multinational assessment of accuracy of equations for predicting risk of kidney failure: A meta-analysis. JAMA 315: 164–174, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kahneman D, Klein G: Conditions for intuitive expertise: A failure to disagree. Am Psychol 64: 515–526, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Da Silva Gane M, Braun A, Stott D, Wellsted D, Farrington K: How robust is the ‘surprise question’ in predicting short-term mortality risk in haemodialysis patients? Nephron Clin Pract 123: 185–193, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moss AH; Renal Physicians Association and the American Society of Nephrology Working Group: Shared decision making in dialysis: A new clinical practice guideline to assist with dialysis-related ethics consultations. J Clin Ethics 12: 406–414, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chiu HH, Tangri N, Djurdjev O, Barrett BJ, Hemmelgarn BR, Madore F, Rigatto C, Muirhead N, Sood MM, Clase CM, Levin A: Perceptions of prognostic risks in chronic kidney disease: A national survey. Can J Kidney Health Dis 2: 53, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manns B, Hemmelgarn B, Lillie E, Dip SC, Cyr A, Gladish M, Large C, Silverman H, Toth B, Wolfs W, Laupacis A: Setting research priorities for patients on or nearing dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1813–1821, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Usvyat LA, Kooman JP, van der Sande FM, Wang Y, Maddux FW, Levin NW, Kotanko P: Dynamics of hospitalizations in hemodialysis patients: Results from a large US provider. Nephrol Dial Transplant 29: 442–448, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kotanko P, Thijssen S, Usvyat L, Tashman A, Kruse A, Huber C, Levin NW: Temporal evolution of clinical parameters before death in dialysis patients: A new concept. Blood Purif 27: 38–47, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Usvyat LA, Barth C, Bayh I, Etter M, von Gersdorff GD, Grassmann A, Guinsburg AM, Lam M, Marcelli D, Marelli C, Scatizzi L, Schaller M, Tashman A, Toffelmire T, Thijssen S, Kooman JP, van der Sande FM, Levin NW, Wang Y, Kotanko P: Interdialytic weight gain, systolic blood pressure, serum albumin, and C-reactive protein levels change in chronic dialysis patients prior to death. Kidney Int 84: 149–157, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Usvyat LA, Raimann JG, Carter M, van der Sande FM, Kooman JP, Kotanko P, Levin NW: Relation between trends in body temperature and outcome in incident hemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 3255–3263, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Usvyat LA, Haviv YS, Etter M, Kooman J, Marcelli D, Marelli C, Power A, Toffelmire T, Wang Y, Kotanko P: The MONitoring Dialysis Outcomes (MONDO) initiative. Blood Purif 35: 37–48, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thijssen S, Wong MM, Usvyat LA, Xiao Q, Kotanko P, Maddux FW: Nutritional competence and resilience among hemodialysis patients in the setting of dialysis initiation and hospitalization. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 1593–1601, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kotanko P, Kooman J, van der Sande F, Kappel F, Usvyat L: Accelerated or out of control: The final months on dialysis. J Ren Nutr 24: 357–363, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duarte CW, Black AW, Murray K, Haskins AE, Lucas L, Hallen S, Han PK: Validation of the Patient-Reported Outcome Mortality Prediction Tool (PROMPT). J Pain Symptom Manage 50: 241–7.e6, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maltoni M, Caraceni A, Brunelli C, Broeckaert B, Christakis N, Eychmueller S, Glare P, Nabal M, Viganò A, Larkin P, De Conno F, Hanks G, Kaasa S; Steering Committee of the European Association for Palliative Care: Prognostic factors in advanced cancer patients: Evidence-based clinical recommendations--a study by the Steering Committee of the European Association for Palliative Care. J Clin Oncol 23: 6240–6248, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jang RW, Caraiscos VB, Swami N, Banerjee S, Mak E, Kaya E, Rodin G, Bryson J, Ridley JZ, Le LW, Zimmermann C: Simple prognostic model for patients with advanced cancer based on performance status. J Oncol Pract 10: e335–e341, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Christakis NA, Lamont EB: Extent and determinants of error in doctors’ prognoses in terminally ill patients: Prospective cohort study. BMJ 320: 469–472, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gwilliam B, Keeley V, Todd C, Roberts C, Gittins M, Kelly L, Barclay S, Stone P: Prognosticating in patients with advanced cancer--observational study comparing the accuracy of clinicians’ and patients’ estimates of survival. Ann Oncol 24: 482–488, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Downing M, Lau F, Lesperance M, Karlson N, Shaw J, Kuziemsky C, Bernard S, Hanson L, Olajide L, Head B, Ritchie C, Harrold J, Casarett D: Meta-analysis of survival prediction with Palliative Performance Scale. J Palliat Care 23: 245–252, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bauman AE, Fardy HJ, Harris PG: Getting it right: Why bother with patient-centred care? Med J Aust 179: 253–256, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weiss NS, Koepsell TD, Psaty BM: Generalizability of the results of randomized trials. Arch Intern Med 168: 133–135, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Petit-Zeman S, Firkins L, Scadding JW: The James Lind Alliance: Tackling research mismatches. Lancet 376: 667–669, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tong A, Chando S, Crowe S, Manns B, Winkelmayer WC, Hemmelgarn B, Craig JC: Research priority setting in kidney disease: A systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis 65: 674–683, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Urquhart-Secord R, Craig JC, Hemmelgarn B, Tam-Tham H, Manns B, Howell M, Polkinghorne KR, Kerr PG, Harris DC, Thompson S, Schick-Makaroff K, Wheeler DC, van Biesen W, Winkelmayer WC, Johnson DW, Howard K, Evangelidis N, Tong A: Patient and caregiver priorities for outcomes in hemodialysis: An international nominal group technique study [published online ahead of print March 8, 2016]. Am J Kidney Dis doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.02.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tallon D, Chard J, Dieppe P: Relation between agendas of the research community and the research consumer. Lancet 355: 2037–2040, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jun M, Manns B, Laupacis A, Manns L, Rehal B, Crowe S, Hemmelgarn BR: Assessing the extent to which current clinical research is consistent with patient priorities: A scoping review using a case study in patients on or nearing dialysis. Can J Kidney Health Dis 2: 35, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Walker SR, Gill K, Macdonald K, Komenda P, Rigatto C, Sood MM, Bohm CJ, Storsley LJ, Tangri N: Association of frailty and physical function in patients with non-dialysis CKD: A systematic review. BMC Nephrol 14: 228, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee SJ, Son H, Shin SK: Influence of frailty on health-related quality of life in pre-dialysis patients with chronic kidney disease in Korea: A cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 13: 70, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Law A, Salter ML, Boyarsky B, Gimenez L, Jaar BG, Walston JD, Segev DL: Frailty as a novel predictor of mortality and hospitalization in individuals of all ages undergoing hemodialysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 61: 896–901, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kutner NG, Zhang R, Huang Y, Painter P: Gait speed and mortality, hospitalization, and functional status change among hemodialysis patients: A US Renal Data System Special Study. Am J Kidney Dis 66: 297–304, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Block G, McAllister CJ, Humphreys MH, Kopple JD: Appetite and inflammation, nutrition, anemia, and clinical outcome in hemodialysis patients. Am J Clin Nutr 80: 299–307, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wallengren O, Lundholm K, Bosaeus I: Diagnostic criteria of cancer cachexia: Relation to quality of life, exercise capacity and survival in unselected palliative care patients. Support Care Cancer 21: 1569–1577, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rodrigues AR, Trufelli DC, Fonseca F, de LC, Del Giglio A: Fatigue in patients with advanced terminal cancer correlates with inflammation, poor quality of life and sleep, and anxiety/depression [published online ahead of print August 30, 2015]. Am J Hosp Palliat Care [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vermeulen J, Neyens JC, van Rossum E, Spreeuwenberg MD, de Witte LP: Predicting ADL disability in community-dwelling elderly people using physical frailty indicators: A systematic review. BMC Geriatr 11: 33, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Suijker JJ, Buurman BM, van Rijn M, van Dalen MT, ter Riet G, van Geloven N, de Haan RJ, Moll van Charante EP, de Rooij SE: A simple validated questionnaire predicted functional decline in community-dwelling older persons: Prospective cohort studies. J Clin Epidemiol 67: 1121–1130, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Beaton K, Grimmer K: Tools that assess functional decline: Systematic literature review update. Clin Interv Aging 8: 485–494, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yao JL, Fang J, Lou QQ, Anderson RM: A systematic review of the identification of seniors at risk (ISAR) tool for the prediction of adverse outcome in elderly patients seen in the emergency department. Int J Clin Exp Med 8: 4778–4786, 2015 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Justice AC, Covinsky KE, Berlin JA: Assessing the generalizability of prognostic information. Ann Intern Med 130: 515–524, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.de Lusignan S, Gallagher H, Chan T, Thomas N, van Vlymen J, Nation M, Jain N, Tahir A, du Bois E, Crinson I, Hague N, Reid F, Harris K: The QICKD study protocol: A cluster randomised trial to compare quality improvement interventions to lower systolic BP in chronic kidney disease (CKD) in primary care. Implement Sci 4: 39, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Donner A, Klar N: Pitfalls of and controversies in cluster randomization trials. Am J Public Health 94: 416–422, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fox CH, Vest BM, Kahn LS, Dickinson LM, Fang H, Pace W, Kimminau K, Vassalotti J, Loskutova N, Peterson K: Improving evidence-based primary care for chronic kidney disease: Study protocol for a cluster randomized control trial for translating evidence into practice (TRANSLATE CKD). Implement Sci 8: 88, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Baker R, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Gillies C, Shaw EJ, Cheater F, Flottorp S, Robertson N, Wensing M, Fiander M, Eccles MP, Godycki-Cwirko M, van Lieshout J, Jäger C: Tailored interventions to address determinants of practice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4: CD005470, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Smith AK, White DB, Arnold RM: Uncertainty--the other side of prognosis. N Engl J Med 368: 2448–2450, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Calice-Silva V, Hussein R, Yousif D, Zhang H, Usvyat L, Campos LG, von Gersdorff G, Schaller M, Marcelli D, Grassman A, Etter M, Xu X, Kotanko P, Pecoits-Filho R: Associations between global population health indicators and dialysis variables in the Monitoring Dialysis Outcomes (MONDO) consortium. Blood Purif 39: 125–136, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]