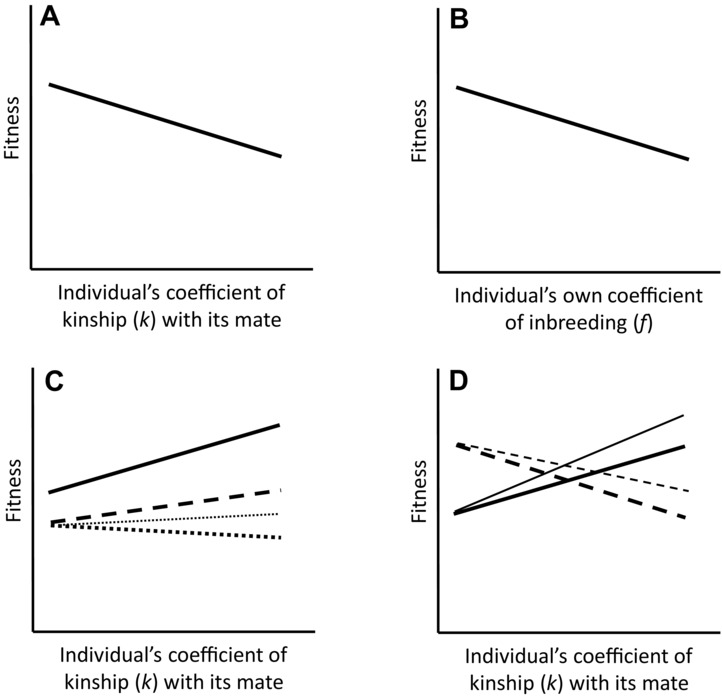

Figure 1.

(A) “Selection on inbreeding”: individuals that pair with more closely related mates (i.e., higher pairwise coefficient of kinship k) are widely postulated to have lower fitness than individuals that pair with less closely related mates, driving evolution of inbreeding avoidance. (B) “Selection on being inbred,” typically termed “inbreeding depression”: individuals that are themselves inbred (i.e., have a higher coefficient of inbreeding f) and hence whose parents were closely related (i.e., high k) commonly have lower fitness than individuals that are less inbred. (C) An individual's initial fecundity could be positively correlated with the degree to which it inbreeds (solid line). Its resulting contribution of descendant organisms to subsequent generations could be positively correlated (thick dashed line) or only weakly negatively correlated (thick dotted line) with the degree to which it inbreeds, despite weak or strong inbreeding depression in offspring survival (causing the differences in slope between the thick solid, dashed, and dotted lines). However, due to the intrinsic transmission advantage of an allele that increases inbreeding, individuals that pair with closer relatives could still contribute more identical‐by‐descent allele copies to subsequent generations, even if they contribute fewer descendant organisms (thin vs. thick dotted lines). (D) The magnitude and direction of selection on inbreeding could potentially differ between males (solid lines) and females (dashed lines) measured in terms of numbers of descendant organisms (thick lines) or identical‐by‐descent allele copies (thin lines).