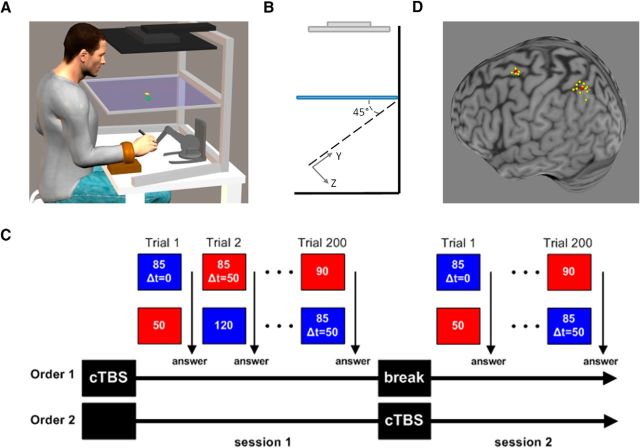

Figure 1.

A, Experimental setup. Participants held the stylus of the robot used to generate virtual force fields while looking at the projected image from an LCD screen placed above their head. Participants' arms were constrained using orthopedic splints so that they could only move the wrist. The virtual environment consisted of a yellow square cursor representing the end point of the stylus and a green square that was used as a button to switch between force fields. The force fields were distinguished by their background color (red or blue). Participants were allowed to perform multiple probing movements and change between the two force fields as many times as they wished. B, Side view of the virtual reality environment. The X–Y plane was rotated by 45°. C, Experimental protocol. The experiment consisted of two sessions. Each session consisted of 200 comparisons between pairs of force fields. In each pair, the stiffness value of one force field was always 85 N/m (standard field) and the second was drawn out of 10 possible stiffness values (comparison field). In half of the trials, the force feedback of the standard field was delayed by 50 ms. After each comparison, participants were asked which field was stiffer. Each participant had PPC cTBS before one of the sessions. D, TMS neuronavigation. Location of each participant's stimulation point (yellow) over the PPC or PMd after normalization into the MNI coordinate system. The average MNI coordinate for each region is indicated in red.