Abstract

Background The Cochrane Consumer Network is an internet‐based community of international users of health care contributing to the work of The Cochrane Collaboration, whose mission is to inform healthcare decision making through development of systematic reviews of best evidence on healthcare interventions.

Objective To prioritize existing review titles listed on The Cochrane Library from a healthcare user perspective, with particular emphasis on patients, carers and health consumers.

Design An online survey was developed and after piloting was made available internationally. The broad dissemination strategy targeted Consumer Network members and Cochrane Review Group editorial staff to identify champions who notified patient support groups and participated in snowballing. The first part of the survey defined criteria that could be applied to review titles and asked survey respondents to rank them. The second part asked respondents to select a health area and prioritize review titles that were of importance to them. Each health area corresponded to a Cochrane Review Group.

Results and discussion Sufficient responses were obtained from 522 valid responses to prioritize review topics in 19 health areas. A total of 321 respondents completed the titles assessment. The types of prioritized interventions were determined by the health area. An important observation was the emphasis on lifestyle and non‐medication therapies in many of the included health areas. The clearest exception to this broad observation was where acute care is required such as antibiotics for acute respiratory tract and HIV‐associated infections and for cardiac conditions. For some cancers, advanced cancer interventions were prioritized. The most important criteria were for the title to convey a clear meaning and the title conveyed that the review would have an impact on health and well‐being. The least important criteria were that the topic was newsworthy or prioritized in the healthcare system.

Conclusion This project was able to identify priority Cochrane review topics for users of health care in 19 of the 50 areas of health care covered by The Cochrane Collaboration. Reviews addressing lifestyle and non‐medical interventions were strongly represented in the prioritized review titles. These findings highlight the importance of developing readable, informative lay summaries to support evidence‐based decision making by healthcare users.

Keywords: consumers in research, health consumer networking, lifestyle and non‐medical interventions, prioritization of synthesized evidence topics

Background

The Cochrane Library 1 is an electronic library containing systematic reviews of the best evidence on healthcare interventions. It is the product of The Cochrane Collaboration, an international not‐for‐profit organization that aims to help people make well‐informed decisions about health care through the use of evidence. The library is a dedicated resource for systematic reviews that the people within the Collaboration strive to regularly update and build on. Evidence‐based or modern medicine is a combination of current best evidence, the expertize of healthcare providers, and patient values and preferences. To be meaningful on an individual level, decision making is inclusive of culture, values and beliefs within a social and geographical environment. The provision of quality health information to patients, carers and clinicians is important for both responsible, shared decision making and effective and safe, patient‐centred health care. 2 , 3

A systematic review sets a clearly formulated healthcare question. The title of a Cochrane review is structured to include the population or type of people studied, the healthcare intervention under investigation and often the outcomes being sought. The authors use systematic and explicit methods to identify, select and critically appraise the relevant best evidence clinical trials, generally randomized controlled trials. The findings from the trials are collated and analysed to draw overall conclusions from the available evidence. Each review has an abstract and a plain language summary that are freely available to those who have access to the internet. Not all internet users are able to access the full review as they are not freely available.

The editorial teams of individual Cochrane Review Groups, each in different healthcare areas such as anaesthesia or colorectal cancers, are responsible for the development of the Cochrane reviews that appear on The Cochrane Library (http://www.thecochranelibrary.com) and which topics they will undertake. The Cochrane Consumer Network (CCNet) is an international community‐based organization of volunteers that operates through the internet as part of The Cochrane Collaboration. Its vision is enhanced accessibility and relevance of Cochrane reviews. Consumers provide a lay user perspective to Cochrane protocols and reviews, assist with developing plain language summaries and help disseminate information from Cochrane reviews. 4 Its members include patients, carers, consumers, representatives of patient support organizations, healthcare providers and others who work closely with patients and consumers.

The relevance of health research and clinical practice guidelines, with a view to improved health outcomes for populations, can improve uptake. Yet consumers’ concerns and priorities are different from those of researchers. 5 In the UK, for example, The National Health Service 6 sets out to ensure that medical research focuses on what is important for patients and users of health care. 7 Carers, patients and consumers of health care do not always differentiate between research and care issues, 8 and their perspectives can be complementary to those of clinicians, providing insight into factors such as respect for cultural background, personal dignity, privacy issues and need for access to information. 9 It is important that consumers and clinicians come together to determine priorities. 10 , 11 This present CCNet project was undertaken to gain some understanding of what systematic review topics on The Cochrane Library, developed by researchers, are of particular interest to users of health care. We particularly targeted patients, carers and health consumers through CCNet and patient support groups.

Objectives

We set out to define the criteria healthcare users may consider in identifying review topics and then to prioritize the titles of existing systematic reviews in The Cochrane Library. This was from a healthcare user perspective, with particular emphasis on patients and health consumers and including healthcare professionals. The intent was for the findings of reviews in these areas to be made more accessible to this audience in updates of the reviews and to contribute to a wider knowledge and understanding of systematic reviews and evidence‐based health care.

Methods

Development of the online survey

Development of criteria

The aim was to gain some insight into what thinking may contribute to how healthcare users would address prioritizing review titles.

The criteria that healthcare users may consider in identifying, accessing and assessing review topics were developed as part of a workshop held at the 2006 Cochrane Colloquium that involved a broad range of participants including consumers, members of Cochrane Review Groups and included invaluable input from researchers in the area of social care. The criteria were as follows: the title of the review clearly conveys its meaning; the topic can be addressed with randomized controlled trials; the healthcare setting is relevant or familiar; the intervention is available to use; the review title suggests to the reader that the review topic has an impact on health and well‐being (for example, ‘Communication skills training for healthcare professionals working with cancer patients, their families and/or carers’); it is a health area that involves self‐management; the health topic is currently newsworthy; it is a prioritized area for the health system; the benefits of the intervention are significant and relevant; the intervention can cause harm, to be weighed against the benefits; the cost of the intervention needs to be weighed against its benefits. Respondent was asked to rate each criterion on a 5‐point scale of not important; fairly important; relatively important; important; or very.

Listing of review titles and survey development

Each of the 50 Cochrane Review Groups with published reviews has an identified area of health care covering a type of health condition, such as heart or peripheral vascular disease, infertility or acute respiratory diseases. The review titles in each area were divided into appropriate broad categories, such as prevention, treatment and rehabilitation for musculoskeletal conditions. The survey required people to read the titles of Cochrane reviews as they appeared on The Cochrane Library (2007, Issue 3).

The survey (Select Survey Software) was piloted by the staff at the German Cochrane Centre before being made available online on the Cochrane Collaboration website (http://www.cochrane.org) from 31st October 2007 to mid‐March 2008. The CCNet Geographical Centres Advisory Group fulfilled the role of advisory group to the project. The CCNet survey collected: relevant personal information from respondents (gender, age group, country of residence, ‘type’ of healthcare user); individual assessments of possible criteria that can be used when prioritizing review titles; an assessment of review titles on one health topic that the respondent selected from the list of 50 review groups. The review titles were assessed as ‘Relevant/Important’; ‘Not Relevant/Not important’; or ‘Unsure’. People could return to the survey to complete further areas of health care. After discussion among the authors, we made the arbitrary decision to make ‘six responses’ the cut‐off for being able to prioritize review titles in a particular health area.

Dissemination of the survey

A comprehensive communication strategy was developed to inform people within and outside of The Cochrane Collaboration about the survey and invite them to participate as users of health care (from 31st October 2007 to mid‐March 2008). Because of the complexity of the survey, the sampling was purposive. The main ways that people found out about the survey were identified as: through the Cochrane Collaboration website (http://www.cochrane.org/); from the Consumer Network e‐mail list (333 subscribers from 55 different countries), electronic newsletter and website accessed through Cochrane.org (http://consumers.cochrane.org/whats‐happening); contact by people within the Collaboration including Managing Editors; from a patient or consumer organization and at the Participa Salute website in Italy (http://www.partecipasalute.it/cms/node/755); and through personal contacts (snowballing).

Informing The Cochrane Collaboration about the findings

Once the survey had been completed and analysed by ranking responses, input and discussion on the prioritized topics and the plain language summaries of the reviews were sought from selected consumers in specific health areas and the appropriate Cochrane Review Groups. These did not alter the prioritized titles.

Plain language summaries are developed as part of a systematic review to provide a non‐technical lay summary of the review and its findings. The summaries are available with the abstract of the review wherever people have access to the internet. A full‐day CCNet responses consumer workshop attended by a total of 12 people from 10 different countries took place at the 2008 Cochrane Colloquium during which the prioritized review topics were further discussed. Guidance for feedback included whether: any general themes could be identified in the prioritized titles; if the plain language summaries for the reviews had a key message and if they were informative, relevant, and useful to consumers and patient support groups.

The prioritized review topics were published on the CCNet website (http://consumers.cochrane.org/whats‐happening) and were available for some 2 years. One author classified the interventions in each health area into the broad categories of screening or prevention; non‐medical, which included education and training, lifestyle, nutrition, self‐management, psychological, physical and complementary therapy interventions; medications; procedures such practices in dentistry and pregnancy and childbirth, surgery, interventional procedures (stents) and radiotherapy. The classifications were then checked by a second author and would have gone to a third author but there was no disagreement.

Results

About the respondents

A total of 522 valid responses were received. Of those who answered the question, 21.3% were men and 73.2% were women (5.5% did not respond to this question). We designated three age ranges: 13.4% of respondents were aged <30 years; 52.5% were 30–55 years; and 28.4% were older than 55 years.

Their country of residence was as follows: North America: 197 (over two‐thirds from US); South America: 23; UK: 72; Scandinavia: 2; Continental Europe: 36; Eastern Europe: 2; Middle East: 43; Africa: 22; Asia: 28; Australia and New Zealand: 95.

Respondents identified themselves as a: caregiver: 12 (2.3%); consumer (advocate): 138 (26.6%); patient: 103 (19.7%); health professional: 107 (20.5%); researcher: 74 (14.2%); other (including journalist, communicator): 48 (9.2%); no answer 7.4%.

Criteria for giving priority to review title

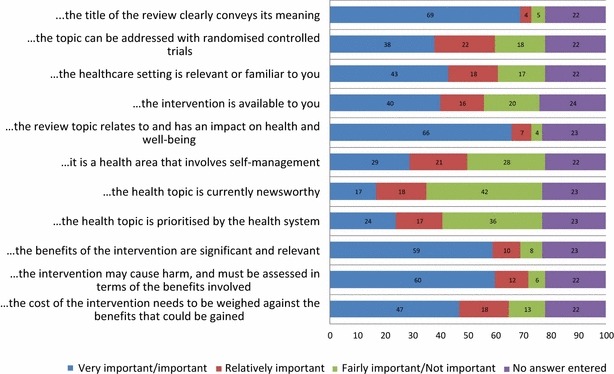

The patient group most often did not provide a rating: 26–27% for each criterion; compared with 20–24% for consumers; 17–18% for healthcare providers; and 16–18% for researchers. The respondents rated 11 criteria on a 5‐point scale: Not Important, Fairly Important, Relatively Important, Important, Very Important. The overall results for the different criteria are given in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

The overall ranking of criteria for consideration when selecting systematic review titles, from 522 responses (numbers are the percentage response for each criterion).

The most important criteria, in the responder groups of consumer (advocate), patient, health professional, researcher, were that the title conveys a clear meaning and the topic has an impact on health and well‐being. That the harms were weighed against the benefits and the intervention had clear benefits were the next highly rated. The least important criteria were newsworthiness; prioritized in the healthcare system. Health professionals and researchers differed from consumers and patients in that they included self‐management as ‘least important’.

Prioritization of review topics – within health areas covered by Cochrane Review Groups

People completing the survey were asked to prioritize the review titles in a selected health area. Completing this part of the survey was challenging as Cochrane review topics are complex and written in medical terms. We did not explain or simplify the titles in any way as this is how they are to be found in The Cochrane Library. The number of respondents who opened this part of the survey but did not provide any answers was between one and three for any area of health care; a total of 25 in all.

We received valid responses from 321 of the 522 respondents to effectively prioritize the titles in 19 health areas. The health areas were as follows: breast cancer (26 responses), consumers and communication (25), depression and anxiety (24), gynaecological cancers (19), pregnancy and childbirth (19) and musculoskeletal (16). The next bracket were as follows: effective practice of care (12), colorectal cancer (11), HIV/AIDS (9), skin (9), back (8), tobacco addiction (8), methodology (8), oral health (7), heart (7), bone joint and muscle trauma (6), acute respiratory infection (6), metabolic and endocrine disorders (6), and pain, palliative and supportive care (6). The prioritized titles were rated as important by at least 70% of respondents. The types of review topics that were prioritized are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

The health topics that received the most responses in the survey classified by type of interventions in the systematic review topic from The Cochrane Library

| Health area (number of reviews) | Number of valid survey responses | Types of interventions addressed by review topic (number of prioritized reviews) | Specific area (number of prioritized reviews) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer (32 reviews) | 26 | Breast cancer (total of 16): | Detection and communication (4); early breast cancer (4, 2 since withdrawn from Library); metastatic and advanced breast cancer (4); side‐effects of treatment (4) |

| Screening and Prevention (3); | |||

| Non‐medical (6); | |||

| Medications (6); | |||

| Medical procedure (1). | |||

| Gynaecological cancers (51 reviews) | 19 | Gynaecological cancer (total of 6): | Advanced cancers (4); management of primary cancer (1); communication skills for healthcare professionals (1) |

| Non‐medical (1); | |||

| Medications (5). | |||

| Colorectal cancer (40 reviews) | 11 | Colorectal cancer (total of 2): | Quality of life after treatment (1); dietary fibre for prevention (1) |

| Prevention (1); | |||

| Medical procedure (1). | |||

| Pain, palliative and supportive care (76 reviews) | 6 | Pain, palliative and supportive care (total of 25): | General pain relief (3), opioids – strong pain killers (analgesics) (2); cancer treatment side‐effects (2); cancer symptoms (9); nutritional support (1); palliative care (8) |

| Non‐medical (8); | |||

| Medications (14); | |||

| Medical procedure (3). | |||

| Heart (60 reviews) | 7 | Heart disease or conditions (total of 12): | Prevention (7); stents for heart pain (angina) (2); atrial fibrillation (3, drug related) |

| Prevention (7); | |||

| Medications (3); | |||

| Medical procedure (2). | |||

| Metabolic and endocrine disorders (48 reviews) | 6 | Metabolic and endocrine diseases (type‐2 diabetes) (total of 9): | Overweight and obesity (2); management of type‐2 diabetes (diet and supplements 3; exercise 2; management 4) |

| Non‐medical (9). | |||

| HIV/AIDS (40 reviews) | 9 | HIV/AIDS (total of 19): | Prevention (5); HIV in pregnancy (3, one since withdrawn); treatments (5); adherence to treatment (!); associated (opportunistic) infections (5) |

| Testing/prevention (4); | |||

| Non‐medical (3); | |||

| Medications (10); | |||

| Medical procedure (2). | |||

| Depression and anxiety (81 reviews) | 24 | Mental health, depression and anxiety (total of 15): | Specifically children and adolescents (4); eating disorders (1); self‐harm (1); adults with non‐medication (2), medications (2); primary care (2); work related (1); other triggers (2) |

| Prevention (1); | |||

| Non‐medical (12); | |||

| Medications (2). | |||

| Musculoskeletal (92 reviews) | 16 | Musculoskeletal conditions (total of 26): | Osteoporosis (3); fibromyalgia (2); shoulder pain (3); osteoarthritis (6); rheumatoid arthritis (9); psoriatic arthritis (1); joint replacement (2) |

| Non‐medical (23); | |||

| Medications (3). | |||

| Back (30 reviews) | 8 | Back and neck pain (total of 21): | Work programs and rehabilitation (5); low‐back pain treatment (8); neck pain (6); lumbar disc surgery (2) |

| Prevention/non‐medical (1); | |||

| Non‐medical (17); | |||

| Medications (2); | |||

| Medical procedure (1). | |||

| Bone joint and muscle trauma (73 reviews) | 6 | Bone, joint and muscle trauma (total of 26): | Older people (6); patellar or heel pain (5, two heel withdrawn); work (2); ligaments and tendons of the hand and shoulder (2), ankle and knee (9); fractures (1); prostheses after amputation (1) |

| Prevention (1), | |||

| Non‐medical (16); | |||

| Medications (2); | |||

| medical procedure (7). | |||

| Acute respiratory infection (78 reviews) | 6 | Acute respiratory infections (total of 13): | Treatment (eight antibiotics, four other), vaccines for preventing influenza in the elderly (1) |

| Non‐medical (2); | |||

| Medications (11). | |||

| Skin (28 reviews) | 9 | Skin problems (total of 7): | Skin conditions (3); fungal infections (2) skin cancers (2) |

| Non‐medical (2); | |||

| Medications (4); | |||

| Medical procedure (1). | |||

| Pregnancy and childbirth (279 reviews) | 19 | Pregnancy and childbirth (total of 41): | During pregnancy (12); childbirth (8) and management of labour (8, one since withdrawn); caesarian sections (5); after giving birth (3); breastfeeding (5) |

| Non‐medical (27); | |||

| Medications (2); | |||

| Procedural (7); | |||

| Medical procedure (5). | |||

| Oral health (74 reviews) | 7 | Oral health (total of 21): | Prevention with fluoride (6), sealants (2); general dental care (7); dental implants and care of (3); cancer (3) |

| Prevention (13); | |||

| Procedural (8). | |||

| Tobacco addiction (45 reviews) | 8 | Tobacco addiction as a risk factor for burden of disease (total of 17): | Prevention and community‐based interventions for young people (3) and adults (1); smoking cessation for young people (1) and adults (6); assistance for (2); and in hospital (3); and primary care (1) |

| Prevention (3); | |||

| Non‐medical (12); | |||

| Medications (2, nicotine replacement, antidepressants) | |||

| Consumers and communication (23 reviews) | 25 | Health professionals communicating with consumers (total of 12) | Communication and decision making (7); communication systems (1); hospital care and discharge (3); healthcare policy (1) |

| Effective practice of care (42 reviews) | 12 | Effective practice and organization of care (total of 10) | Health system approaches (5); professional practice and continuing education (5) |

| Methodology (12 reviews) | 8 | Methodological reviews (total of 7) | Participation in trials (4); peer review and publication of results (3) |

The prioritized titles were listed on the CCNet webpages under the Review Groups and with a short statement about the review, obtained from the plain language summary or abstract of the review, until the end of 2010. We have listed the health topics that received sufficient responses to prioritize review topics, the types of interventions covered in the prioritized reviews (for example, exercise, drug treatments or surgery) and a further description of the specific area addressed within that topic in Table 1.

The limitations of the survey were the sampling technique, where we could not determine what proportion of people responded to our survey; the length of the survey, particularly for health areas with large numbers of review titles such as in pregnancy and childbirth; the complex language of the review titles; and the overlap of titles between some Cochrane Review Groups. Moreover, the limited number of respondents for a particular health area meant we pooled all healthcare users whether they were consumers or healthcare providers and from all countries. The small number of responses in some health areas (<6) meant that we lost that information as it could not be used in the prioritized titles.

Discussion

The online survey identified 19 health areas represented on The Cochrane Library that we were able to prioritize from a healthcare user perspective. Every effort was made to notify a broad range of consumer and patient support organizations about the online survey, through e‐mail and snowballing. People also responded to current health issues for their families (personal communication). It is likely that the identified health areas are related to the interests of its members in promoting evidence‐based quality health care (effective practice of care, consumers and communication, methodology) as identified in the evaluation of the Network 4 ; the Consumer Network links with well‐networked and informed consumers and with patient support groups, for example, in HIV/AIDS, with the Association of Cancer Online Resources http://www.acor.org (breast, gynaecological, colorectal, skin cancers and palliative care), mental health (depression and anxiety) and musculoskeletal organizations, and the extent that Cochrane Review Groups involve consumers and users of health care interventions (such as in pregnancy and childbirth, respiratory infectious diseases). This was a virtual project so how organized social networking is for a group of patients played a role. Other areas such as metabolic and heart disease, oral health and tobacco addiction are of general interest to the wider community. Having the survey as news on the Cochrane website was also effective.

This was an ambitious project that could not have been attempted without the infrastructure of The Cochrane Collaboration. Further projects more focused on the characteristics of healthcare users, that is, age, level of education and health literacy, country of origin, first language, background, and socioeconomic level, are needed to better define priority topics in the different health areas.

Over half of the responses were from people aged 30 to 55 years of age and nearly three quarters were from women. Over two‐thirds were from North America (US and Canada) but with responses from as widespread as Australasia, UK, the Middle East, Continental Europe, South America and Africa. The largest group identified themselves as consumer advocates or representatives (over a quarter); with similar numbers of patients and health professionals (around 20% each). When asked to assess the criteria, they might use in prioritizing review topics, the first section of the survey, all three groups considered that the title conveys a clear meaning and the topic has an impact on health and well‐being. The clear difference between healthcare providers and the other two groups was the priority given to self‐management, which was less important for the providers. That healthcare providers and patients and their carers differ in their perspective on management of a chronic illness is well documented by Yen et al. 12 where the patients were attempting to balance their illness with living, and the providers were concerned about compliance to treatment and care plans. We therefore grouped all responses in the second section of the survey that prioritized review topics. This was also necessary because of the small number of responses for health areas.

An important observation from the healthcare user prioritized reviews is their emphasis on lifestyle and non‐medication therapies in most, but not all, health areas under consideration. This relates well to the identification of the impact on health and well‐being with clear benefits over harms as important criteria. It also affirms the literature where Tallon et al. 13 identified that people with osteoarthritis of the knee favoured physiotherapy, surgery, education and coping strategies over drugs. The Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group 14 reported the results of a 2004 survey clearly indicating that consumers want information about complementary and alternative treatment options that they can implement themselves. Consumers also identified the need for more drug to drug comparisons, as most systematic reviews focused on drug to placebo comparisons. The present project identified the important review topics in the area of type‐2 diabetes and metabolic disorders as diet and exercise for overweight and obesity; diet, exercise, fish oil for type‐2 diabetes; and its management with training for self‐management strategies, self‐monitoring of blood glucose, interventions for improving keeping to treatment schedules and using routine surveillance systems. The types of reviews that Sakala et al. 15 identified as of greatest interest for consumers in the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group were those that delineate appropriate standards of care for childbearing women and an understanding of low‐technology low‐risk solutions. Thus, review topics that those consumers identified and which were prioritized in our survey involve interventions for smoking cessation, psychosocial and psychological interventions for antenatal depression, external cephalic version for breech presentation at term, continuous support for women during childbirth, immersion in water in labour, position in the second stage of labour for women without epidural anaesthesia, early skin‐to‐skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants and support for breastfeeding mothers.

The areas with the clearest exceptions to this broad observation are where acute care is required such as antibiotics for acute respiratory tract infections; HIV‐associated infections; treatment of cardiac conditions. In breast and gynaecological cancers, advanced cancer interventions were prioritized, as was palliative care. This could be in line with more informed consumers and patients through a strong education and research component in breast cancer support networks, for example, project LEAD. 16

The prioritization project also highlights the importance of clear messages from Cochrane reviews for users of health care. This is in reference to the findings of the reviews in terms of the availability of well‐conducted clinical trials of well‐defined applicable interventions with longer‐term and patient‐defined outcomes 17 , 18 and the Cochrane methodology in terms of assessing both benefits and harms and its reliance on randomized controlled trials. The Cochrane Collaboration provides plain language summaries for this purpose, and the intent of this project was to encourage and further develop this work. Randomized controlled trials are not always the best approach for assessing healthcare interventions. Examples are addressing the use of caesarean sections for non‐medical reasons at term, home vs. hospital births and end‐of‐life‐care pathways. 19 Sometimes the messages from Cochrane reviews are not pleasant for users of health care, such as where treatments for patients with cancer (erythropoietin or darbepoetin) are associated with increased on‐study mortality and worsened overall survival: ‘It told us in black and white terms what we don’t know in research – that’s important but disappointing’.

The Cochrane Library contains over 3500 reviews covering a broad range of healthcare interventions in many diseases and health conditions. Surveys by the publishers have identified patients and consumers as a small component of the people downloading full Cochrane reviews. The prioritization project highlights the importance of clear messages from Cochrane reviews for users of health care. This not only includes the findings of the review but how the Cochrane methodology uses relatively short‐duration randomized controlled trials as best evidence with mainly quantitative, biomedical outcomes and frequent limitations in the availability of high quality clinical trials to review. Trials are often restricted in terms of settings and populations, as with low‐income countries. Many of the included trials compare the intervention with non‐active placebo or no treatment, to determine efficacy, whereas users of health care may be more interested in directly comparing one drug with another. Glenton et al. 20 undertook an iterative process involving semi‐structured interviews to determine how the findings of a Cochrane systematic review could be standardized and consistently presented in summaries to gain greater understanding. The authors acknowledged that consumer peer review of the summaries, as practized in The Cochrane Collaboration, 4 could help to develop a background section that is more understandable and relevant to a consumer audience.

Conclusions

The Cochrane Consumer Network has successfully identified priority review topics for users of health care in 19 healthcare areas. An important observation from the consumer prioritized reviews is their emphasis on lifestyle and non‐medication therapies with less acute medical conditions. Reviews addressing lifestyle and non‐medical interventions were strongly represented in the prioritized topics, particularly in the areas of metabolic disorders, musculoskeletal conditions and pregnancy and childbirth. These findings highlight the importance of developing readable, informative plain language summaries to support evidence‐based decision making by healthcare users, which is supportive of the work that the editorial teams in these areas are already undertaking.

In line with health services and health care being important to users, communication between professionals and effective practice of care were also priority areas.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the Cochrane Collaboration Steering Group for funding of prioritization projects; Australian Department of Health and Ageing funding for Cochrane activities in Australia; 2006 Cochrane Colloquium: Sara Morris and Esther Coren of the UK; Gerd Antes and the staff at the German Cochrane Centre. CCNet members including the CCNet Geographical Centres Advisory Group; Carol Sakala, Sandi Pniauskas, Andrew Herxheimer and Amy Zelmer.

Appendix: prioritized reviews

*Top 50 reviews in The Cochrane Library (2007)

#Reviews that have since been withdrawn from The Cochrane Library (9 January 2009)

Cancer

Breast cancer

Detection and communication (rather than diagnosis):

*Screening for breast cancer with mammography

Strategies for increasing the participation of women in community breast cancer screening

Regular self‐examination or clinical examination for early detection of breast cancer

Methods of communicating a primary diagnosis of breast cancer to patients

Early breast cancer:

Follow‐up strategies for women treated for early breast cancer

Pre‐operative chemotherapy for women with operable breast cancer

Metastatic and advanced breast cancer:

Psychological interventions for women with metastatic breast cancer (support group sessions)

Chemotherapy alone vs. endocrine therapy alone for metastatic breast

Systemic therapy for treating locoregional recurrence in women with breast cancer

Aromatase inhibitors for treatment of advanced breast cancer in post‐menopausal women

Side effects of treatment:

Exercise for women receiving adjuvant therapy for breast cancer

Chinese medicinal herbs to treat the side‐effects of chemotherapy in breast cancer patients

Physical therapies for reducing and controlling lymphoedema of the limbs

Antibiotics, anti‐inflammatories for reducing acute inflammatory episodes in lymphoedema of the limbs

#Tamoxifen and Radiotherapy for early breast cancer (two separate reviews)

Colorectal cancer

Quality of life after rectal resection for cancer, with or without permanent colostomy

Dietary fibre for the prevention of colorectal adenomas and carcinomas

Gynaecological cancer

Communication skills training for health care professionals working with cancer patients, their families and/or carers

Intraperitoneal chemotherapy for the initial management of primary epithelial ovarian cancer

Chemotherapy for advanced ovarian cancer

Tamoxifen for relapse of ovarian cancer

Short vs. long duration infusions of paclitaxel for any advanced adenocarcinoma

Oral anticoagulation for prolonging survival in patients with cancer

Pain, palliative and supportive care

General pain relief:

Music for pain relief

Touch therapies for pain relief in adults (New)

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for chronic pain

Opioids – strong pain killers (analgesics):

Patient controlled opioid analgesia vs. conventional opioid analgesia for post‐operative pain

Opioids for neuropathic pain (caused by nerve damage)

Cancer:

Acupuncture‐point stimulation for chemotherapy‐induced nausea or vomiting

Selenium for alleviating the side‐effects of chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgery in cancer patients

Cancer pain:

NSAIDS or paracetamol, alone or combined with opioids

Oral morphine

Hydromorphone for acute and chronic pain

Opioids for the management of breakthrough (episodic) pain

Opioid switching to improve pain relief and drug tolerability

Ketamine as an adjuvant to opioids for cancer pain (additional treatment)

Comparative efficacy of epidural, subarachnoid and intracerebroventricular opioids in patients with pain because of cancer

Other:

Nutrition support for bone marrow transplant patients

Palliative care:

Laxatives for the management of constipation in palliative care patients

Benzodiazepines and related drugs for insomnia in palliative care

Opioids for the palliation of breathlessness in terminal illness

Drug therapy for anxiety in palliative care

Drug therapy for delirium in terminally ill patients

Radiotherapy for the palliation of painful bone metastases

Pleurodesis for malignant pleural effusions

Surgery for the resolution of symptoms in malignant bowel obstruction in advanced gynaecological and gastrointestinal cancer

#Aromatherapy and massage for symptom relief in patients with cancer

Cardiovascular and diabetes mellitus

Heart disease or conditions

Prevention:

Dietary advice for reducing cardiovascular risk

Low glycaemic index diets for coronary heart disease

Interventions for promoting physical activity

Multiple risk factor interventions for primary prevention of coronary heart disease

Omega 3 fatty acids for prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease

Reduced or modified dietary fat for preventing cardiovascular disease

*Interventions for preventing obesity in children

Stents for heart pain (angina):

Early invasive vs. conservative strategies for unstable angina and non‐ST‐elevation myocardial infarction in the stent era

Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty with stents vs. coronary artery bypass grafting for people with stable angina or acute coronary syndromes

Atrial fibrillation:

Pharmacological cardioversion for atrial fibrillation and flutter

Anticoagulation for heart failure in sinus rhythm

Antiplatelet agents vs. control or anticoagulation for heart failure in sinus rhythm

Metabolic and endocrine diseases

Over weight and obesity:

*Low glycaemic index or low glycaemic load diets

*Exercise

Diabetes–type 2 diabetes mellitus:

Dietary advice for treatment in adults

*Exercise

Fish oil

Management of type 2 diabetes mellitus:

Group‐based training for self‐management strategies

Interventions for improving adherence to treatment recommendations

Self‐monitoring of blood glucose in patients not using insulin

Systems for routine surveillance for people with diabetes mellitus

HIV/AIDS

Prevention

Population based:

Population‐based interventions for reducing sexually transmitted infections, including HIV infection.

Mass media interventions for promoting HIV testing

Condom effectiveness in reducing heterosexual HIV transmission

Male circumcision for prevention of heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men

Antiretroviral post‐exposure prophylaxis (PEP) for occupational HIV exposure

HIV in pregnancy:

Efficacy and safety of cesarian delivery for prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission

Antiretrovirals for reducing the risk of mother‐to‐child transmission of HIV

Treatments for people with HIV/AIDS:

Stavudine, lamivudine and nevirapine combination therapy for treatment of HIV infection and AIDS in adults

Micronutrient supplementation in children and adults

Nutritional interventions for reducing morbidity and mortality

Treatment for anemia

Interventions for the prevention and management of oral thrush (oropharyngeal candidiasis) in adults and children

Adherence to treatment:

Patient support and education for promoting adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AID

HIV – associated (opportunistic) infections:

Treatment of latent tuberculosis infection

Adjunctive corticosteroids for Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia

Antifungal interventions for the primary prevention of cryptococcal disease in adults

Cotrimoxazole prophylaxis for opportunistic infections in children

Cotrimoxazole prophylaxis for opportunistic infections in adults

#Interventions for reducing the risk of mother‐to‐child transmission (obsolete)

Mental health

Depression and anxiety

Children and adolescents:

Exercise in prevention and treatment of anxiety and depression among children and young people.

Cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents

Psychological and/or educational interventions for the prevention of depression in children and adolescents

Interventions for helping people recognize early signs of recurrence in bipolar disorder

Eating disorders:

Self‐help and guided self‐help for eating disorders

Self‐harm:

Psychosocial and pharmacological treatments for deliberate self‐sharm

Adults:

Non‐medication therapies:

Meditation therapy for anxiety disorders

Psychological therapies for generalized anxiety disorder

Medications:

Antidepressants for generalized anxiety disorder

Antidepressants plus benzodiazepines for major depression

Primary Care:

Psychosocial interventions by general practitioners

Effectiveness and cost effectiveness of counseling in primary care

Work related:

Preventing occupational stress in healthcare workers

Other triggers:

*Psychological treatment of post‐traumatic stress disorder

Combined psychotherapy plus antidepressants for panic disorder with or without agoraphobia

Injuries and musculoskeletal

Back and neck pain

Work programs:

Manual material handling advice and assistive devices for prevention and treatment

Work conditioning, work hardening and functional restoration

Back schools for non‐specific low‐back pain

Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for subacute low‐back pain

Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for neck and shoulder pain

Treatment for low‐back pain:

Massage therapy

*Exercise therapy

Spinal manipulative therapy for low‐back pain

Bed rest for acute low‐back pain and sciatica

Behavioural treatment for chronic pain

Muscle relaxants

Neuroreflexotherapy

TENS for chronic pain

Neck Pain:

Acupuncture

Electrotherapy for neck disorders

Massage

Exercises

Manipulation and mobilization

Medicinal and injection therapies

Surgery:

Surgical interventions for lumbar disc prolapse

Rehabilitation after lumbar disc surgery

Bone, joint and muscle trauma

Older people:

*Interventions for preventing falls

Vitamin D and vitamin D analogues for preventing fractures associated with osteoporosis

Progressive resistance strength training for physical disability

Mobilization strategies after hip fracture surgery

Co‐ordinated multidisciplinary approaches for inpatient rehabilitation of older patients with hip (proximal femoral) fractures

Hip fracture aftercare

Pain:

*Exercise therapy for patellofemoral pain syndrome

Medications (pharmacotherapy) for patellofemoral pain syndrome

Interventions for treating plantar heel pain

Work related:

Ergonomic and physiotherapeutic interventions for treating work‐related complaints of the arm, neck or shoulder

Biopsychosocial rehabilitation for upper limb repetitive strain

Ligaments and tendons – hand and shoulder:

Rehabilitation after surgery for flexor tendon injuries in the hand

Interventions for tears of the shoulder (rotator cuff) in adults

Ligaments and tendons – ankles and knees:

Different functional treatment strategies for ankle sprains (acute lateral ankle ligament injuries) in adults

Interventions for treating long‐term (chronic) ankle instability

Therapeutic ultrasound for acute ankle sprains

Exercise for treating isolated anterior cruciate ligament injuries in adults

Surgical vs. conservative interventions for anterior cruciate ligament ruptures in adults

Exercise for treating anterior cruciate ligament injuries in combination with collateral ligament and meniscal damage of the knee in adults

Interventions for treating posterior cruciate ligament injuries of the knee in adults

Surgical treatment for meniscal injuries of the knee in adults

Autologous cartilage implantation for full thickness articular cartilage defects of the knee

Fractures:

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for promoting fracture healing and treating fracture non‐union

Amputation:

Prescription of prosthetic ankle‐foot mechanisms after lower limb amputation

#Orthotic devices for treating patellofemoral pain syndrome

#Interventions for treating calcaneal (heel) fractures

Musculoskeletal conditions

Osteoporosis:

Vitamin D and vitamin D analogues for preventing fractures

Calcium and vitamin D for corticosteroid‐induced osteoporosis

Exercise for preventing and treating osteoporosis in post‐menopausal women

Fibromyalgia:

Exercise for treating fibromyalgia syndrome

Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for fibromyalgia and musculoskeletal pain in working age adults

Shoulder pain:

Acupuncture

Corticosteroid injections for rotator cuff disease, adhesive capsulitis or frozen shoulder

*Physiotherapy interventions

Osteoarthritis:

Exercise for the knee

Intensity of exercise for treatment

Braces and moulded inner soles for shoes (orthoses) for treating osteoarthritis of the knee

*Glucosamine therapy

Therapeutic ultrasound for osteoarthritis of the knee

Thermotherapy

Joint replacement:

Pre‐operative education for hip or knee replacement

Continuous passive motion following total knee arthroplasty

Rheumatoid arthritis:

Patient education for adults

Splints and moulded inner soles for shoes (orthoses)

Occupational therapy for rheumatoid arthritis

Low level laser therapy (Classes I, II and III)

Acupuncture and electroacupuncture

Tai chi

Thermotherapy

Moderate‐term, low‐dose corticosteroids

Folic acid and folinic acid for reducing side‐effects in patients receiving methotrexate

Psoriatic Arthritis:

Interventions for treating psoriatic arthritis

Pregnancy and childbirth

Pregnancy and childbirth

During pregnancy (antenatal):

Individual or group antenatal education for childbirth or parenthood, or both

Giving women their own case notes to carry during pregnancy

Interventions for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy

Interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy

Interventions for preventing and treating pelvic and back pain in pregnancy

Psychosocial and psychological interventions for treating antenatal depression

Antenatal day care units vs. hospital admission for women with complicated pregnancy

Ultrasound for fetal assessment in early pregnancy

External cephalic version for breech presentation at term

External cephalic version for breech presentation before term

Antenatal education for self‐diagnosis of the onset of active labour at term

Antenatal perineal massage for reducing perineal trauma

Supporting childbirth:

Continuity of caregivers for care during pregnancy and childbirth

*Continuous support for women during childbirth

Traditional birth attendant training for improving health behaviours and pregnancy outcomes

Home‐like vs. conventional institutional settings for birth

Home vs. hospital birth

Immersion in water in pregnancy, labour and birth

Acupuncture for induction of labour

Labour assessment programs to delay admission to labour wards

Management of labor:

Position in the second stage of labour for women without epidural anaesthesia

*Epidural vs. non‐epidural or no analgesia in labour

*Complementary and alternative therapies for pain management in labour

Early vs. delayed umbilical cord clamping in preterm infants

Episiotomy for vaginal birth

*Early skin‐to‐skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants

Induction of labour for improving birth outcomes for women at or beyond term

Active vs. expectant management in the third stage of labour

Caesarians and interventions:

Caesarean section for non‐medical reasons at term

Regional vs. general anaesthesia for caesarean section

Planned caesarean section for term breech delivery

Elective repeat caesarean section vs. induction of labour for women with a previous caesarean birth

Planned elective repeat caesarean section vs. planned vaginal birth for women with a previous caesarean birth

After giving birth (post‐natal):

Early post‐natal discharge from hospital for healthy mothers and term infants

Psychosocial and psychological interventions for preventing post‐partum depression

Breastfeeding:

*Interventions for promoting the initiation of breastfeeding

Interventions in the workplace to support breastfeeding for women in employment

*Support for breastfeeding mothers

Optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding

Support for mothers, fathers and families after perinatal death

#Expediated vs. conservative approaches for vaginal delivery in breech presentation

Risk factors

Tobacco addiction – risk factor for burden of disease

Prevention and community‐based

Young people:

Community interventions for preventing smoking in young people

Family and carer smoking control programmes for reducing children’s exposure to environmental tobacco smoke

School‐based programmes for preventing smoking

Adults:

Community interventions for reducing smoking among adults

Smoking cessation:

Young people:

Tobacco cessation interventions for young people

Adults:

*Nicotine replacement therapy

Self‐help interventions

Exercise interventions

*Antidepressants

Workplace interventions

Interventions for smokeless tobacco use cessation

Providing assistance:

Enhancing partner support to improve smoking cessation

Group behaviour therapy programmes

In hospital:

Interventions for pre‐operative smoking cessation

Interventions for smoking cessation in hospitalized patients

Nursing interventions for smoking cessation

General practice or primary care:

Training health professionals in smoking cessation

Communication and organization of health services

Health professionals communicating with consumers

Communication and decision making:

Interventions before consultations for helping patients address their information needs

Interventions for improving older patients’ involvement in visits to their general physicians (primary care givers)

Interventions for providers to promote a patient‐centred approach in clinical consultations

Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions

Personalized risk communication for informed decision making about taking screening tests

Contracts between patients and healthcare practitioners for improving patients’ adherence to treatment prevention and health promotion activities

Interventions to support the decision‐making process for older people facing the possibility of long‐term residential care

Communication systems:

Interactive health communication applications for people with chronic disease

Hospital care and discharge:

Written and verbal information vs. verbal information only for patients being discharged from acute hospital settings to home

*Family‐centred care for children in hospital

Telephone follow‐up, initiated by a hospital‐based health professional, for post‐discharge problems in patients discharged from hospital to home

Policy:

Methods of consumer involvement in developing healthcare policy and research, clinical practice guidelines and patient information material

Effective practice and organization of care

Health system approaches:

Effectiveness of shared care across the interface between primary and specialty care in chronic disease management

Guidelines in professions allied to medicine

*Substitution of doctors by nurses in primary care

*Interventions to improve hand hygiene compliance in patient care

Mass media interventions for influencing the use of health services

Professional practice and continuing education:

Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes

Interprofessional education: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes

Tailored interventions to overcome identified barriers to change: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes

Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes

Teaching critical appraisal skills in health care settings

Acute conditions

Acute respiratory infections

Children:

*Antibiotics for acute otitis media

Antibiotics for bronchiolitis

Antibiotics for community acquired lower respiratory tract infections secondary to mycoplasma pneumoniae

Antibiotics for community acquired pneumonia

Humidified air inhalation for treating croup

Advising patients to increase fluid intake for treating acute respiratory infections

Bronchodilators for infants with bronchiolitis

Corticosteroids for acute bacterial meningitis

Adults:

Antibiotics for acute laryngitis

Antibiotics for acute maxillary sinusitis

Antibiotics for community‐acquired pneumonia in adult outpatients

Antibiotic prophylaxis to reduce respiratory tract infections and deaths in intensive care

Elderly:

Vaccines for preventing influenza in the elderly

Other

Oral health

Fluoride for preventing dental caries–children and adolescents:

Fluoride toothpastes

Fluoride mouthrinses

Topical fluoride (toothpastes, mouthrinses, gels or varnishes)

Fluoride gels

Fluoride varnishes

One topical fluoride (toothpastes, or mouthrinses, or gels, or varnishes) vs. another

Sealants for preventing dental decay–children and adolescents:

Pit and fissure sealants for permanent teeth

Pit and fissure sealants vs. fluoride varnishes

General dental care:

Manual vs. powered toothbrushing for oral health

Tongue scraping for treating halitosis

Mouthrinses for halitosis

Routine scale and polish for periodontal health in adults

Recall intervals for oral health in primary care patients

Interventions for treating asymptomatic impacted wisdom teeth in adolescents and adults

Complete or ultraconservative removal of decayed tissue in unfilled teeth

Interventions for dental implants–replacing missing teeth:

Maintaining health around dental implants

Treatment of perimplantitis

Preprosthetic surgery vs. dental implants

Cancer:

*Interventions for treating oral mucositis for patients with cancer receiving treatment

Screening programmes for the early detection and prevention of oral cancer

Interventions for treating oral leukoplakia (to prevent from becoming cancerous)

Skin problems

Fungal infections:

Topical treatments for fungal infections of the skin and nails of the foot

Oral treatments for fungal infections of the skin of the foot

Skin conditions:

Eczema:

Psychological and educational interventions for atopic eczema in children

Chinese herbal medicine for atopic eczema

Impetigo:

Interventions for impetigo

Cancers:

Interventions for basal cell carcinoma of the skin

Statins and fibrates for preventing melanoma

Methodological reviews

Participation in trials:

Outcomes of patients who participate in randomized controlled trials compared to similar patients receiving similar interventions who do not participate

Randomization to protect against selection bias in healthcare trials

Strategies to improve recruitment to research studies

Incentives and disincentives to participation by clinicians in randomized controlled trials

Peer review and publication:

Editorial peer review for improving the quality of reports of biomedical studies

Full publication of results initially presented in abstracts

Peer review for improving the quality of grant applications

The Cochrane Collaboration. The authors came from Australia, Argentina, USA, South Africa and UK, and Germany.

This work was presented by Maria Belizán as a paper entitled ‘Prioritization of Cochrane reviews for consumers and the public in low‐ and high‐income countries as a way of promoting evidence‐based health care’ at a special oral session: Assessing mechanisms for the prioritization of review topics in The Cochrane Collaboration (Singapore, October 2009) at the Cochrane Colloquium.

References

- 1. The Cochrane Library . Available at http://www.thecochranelibrary.com; plain language summaries and abstracts at http://www2.cochrane.org/reviews

- 2. Bauman AE, Fardy HJ, Harris PG. Getting it right: why bother with patient‐centred care? The Medical Journal of Australia, 2003; 179: 253–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chalmers I, Glasziou P. Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Lancet, 2009; 374: 86–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wale JL, Colombo C, Belizan M, Nadel J. International health consumers in the Cochrane Collaboration: 15 years on. The Journal of Ambulatory Care, 2010; 33: 182–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Williamson C. What does involving consumers in research mean [Editorial]. The Quarterly Journal of Medicine, 2001; 94: 661–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Department of Health . Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care. London: Department of Health, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boote J, Telford R, Cooper C. Consumer involvement in health research: a review and research agenda. Health Policy, 2002; 61: 213–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Owens C, Levy A, Aitken P. Do different stakeholder groups share mental research priorities? A four‐arm Delphi study. Health Expectations, 2008; 11: 418–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Black N, Jenkinson C. Measuring patients’ experiences and outcomes [Analysis]. BMJ, 2009; 339: b2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Partridge N, Scadding J. The James Lind Alliance: patients and clinicians should jointly identify their priorities for clinical trials. Lancet, 2004; 364: 1923–1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. James Lind Alliance . Available at http://www.lindalliance.org/tackling_treatment_uncertainties_together.asp; database of uncertainties of the effects of treatments (DUETs) at http://www.library.nhs.uk/duets/ (last accessed August 2010).

- 12. Yen L, Gillespie J, Jeon Y‐H et al. Health professionals, patients and chronic illness policy: a qualitative study. Health Expectations, 2011; 14: 10–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tallon D, Chard J, Dieppe P. Relation between agendas of the research community and the research consumer. Lancet, 2000; 355: 2037–2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shea B, Santesso N, Qualman A et al. Consumer‐driven health care: building partnerships in research. Health Expectations, 2005; 8: 352–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sakala C, Gyte G, Henderson S, Neilson JP, Horey D. Consumer‐professional partnership to improve research: the experience of the Cochrane Collaboration’s pregnancy and Childbirth Group. Birth, 2001; 28: 133–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dickersin K, Braun L, Mead M et al. Development and implementation of a science training course for breast cancer activists: project LEAD (leadership, education and advocacy development). Health Expectations, 2001; 4: 213–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Belizán JM, Belizán M, Mazzoni A et al. Maternal and child health research focusing on interventions that involve consumer participation. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 2010; 108: 154–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kelson M. Consumer collaboration, patient‐defined outcomes and the preparation of Cochrane reviews. Health Expectations, 1999; 2: 129–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wee B, Hadley G, Derry S. How useful are systematic reviews for informing palliative care practice? Survey of 25 Cochrane systematic reviews BMC Palliative Care, 2008; 7: 13 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2532992/ . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Glenton C, Santesso N, Rosenbaum S et al. Presenting the results of Cochrane systematic reviews to a consumer audience: a qualitative study. Medical Decision Making, 2010; 30: 566–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]