Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of ustekinumab through 2 years in adult patients with active psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

Methods

A total of 615 adult patients with active PsA were randomized to placebo, ustekinumab 45 mg, or ustekinumab 90 mg, at weeks 0, 4, and every 12 weeks through week 88 (last dose). At week 16, patients with <5% improvement in both tender and swollen joint counts entered blinded early escape (placebo to 45 mg, 45 mg to 90 mg, and 90 mg to 90 mg). All remaining placebo patients crossed over to ustekinumab 45 mg at week 24. Clinical efficacy measures included American College of Rheumatology criteria for 20% improvement (ACR20), Disease Activity Score in 28 joints using the C‐reactive protein level (DAS28‐CRP), and ≥75% improvement in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI75). Radiographic progression was evaluated using the modified Sharp/van der Heijde score (SHS).

Results

At week 100, ACR20, DAS28‐CRP moderate/good response, and PASI75 rates ranged from 56.7–63.6%, 71.9–76.7%, and 63.9–72.5%, respectively, across the 3 treatment groups. In both ustekinumab groups, the median percent improvement in dactylitis and enthesitis was 100% at week 100. The mean changes in SHS score from week 52 to week 100 were similar to those observed from week 0 to week 52 in the ustekinumab groups. Through week 108, 70.7% and 9.7% of patients had an adverse event (AE) or serious AE, respectively. The rates and type of AEs were similar between the dose groups.

Conclusion

Clinical and radiographic benefits from ustekinumab treatment were maintained through week 100 in the PSUMMIT 1 study. No unexpected safety events were observed; the safety profile of ustekinumab in this population was similar to that previously observed in psoriasis patients treated with ustekinumab.

INTRODUCTION

A considerable proportion of patients with psoriasis also develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA) 1, 2, which can affect peripheral joints, the axial skeleton, and entheses and can be associated with psoriatic skin and nail involvement 3. Myriad consequences of this clinical constellation adversely impact patients’ physical function, work productivity, and health‐related quality of life (HRQOL) 3, 4. PsA can be effectively treated with disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and biologic anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents, yet not all patients respond to these modalities. There is evidence that interleukin‐23 (IL‐23) may be involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis and PsA, thereby providing an additional potential treatment target 5.

Box 1. Significance & Innovations.

Improvements in the signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis and inhibition of radiographic progression were maintained through 2 years of ustekinumab therapy in adult patients with active disease.

No unexpected safety events were observed through 2 years, and results were consistent with the known safety profile of ustekinumab.

Ustekinumab, a monoclonal anti–IL‐12/23p40 antibody, is approved for the treatment of PsA and plaque psoriasis 6. PSUMMIT 1 was one of two phase 3 trials of ustekinumab in adults with active PsA 7. Through week 24 of PSUMMIT 1, patients treated with ustekinumab had significantly greater overall improvements in joint‐ and skin‐related symptoms, physical function, dactylitis, and enthesitis compared with placebo 7. An integrated analysis with PSUMMIT 2 demonstrated significantly less radiographic progression at week 24 for ustekinumab‐treated patients versus placebo 8. Clinical efficacy and inhibition of radiographic progression were sustained through week 52 of PSUMMIT 1 7, 8. Here we report the final safety and efficacy results from PSUMMIT 1 through 2 years.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients and study design

The patient population and study design of the randomized, placebo‐controlled phase 3 PSUMMIT 1 trial were previously detailed 7. Briefly, anti‐TNF–naive adults with active PsA for ≥6 months previously treated with or intolerant to DMARDs (≥3 months) or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; ≥4 weeks) were eligible. Patients were randomized to placebo, ustekinumab 45 mg, or ustekinumab 90 mg at weeks 0 and 4 and every 12 weeks, with placebo crossover to ustekinumab 45 mg at weeks 24 and 28, and every 12 weeks, through week 88. At week 16, patients with <5% improvement in tender/swollen joint counts entered blinded early escape (placebo to ustekinumab 45 mg; ustekinumab 45 mg to 90 mg); patients randomized to ustekinumab 90 mg did not have treatment adjustments. Continuation of concomitant stable baseline doses of methotrexate (MTX), NSAIDs, or oral corticosteroids was permitted. After week 52, adjustments to concomitant medication doses and initiation of other concomitant therapies were permitted.

PSUMMIT 1 was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by each site's institutional review board/ethics committee. All patients gave written informed consent before any study‐related procedures were performed.

Assessments

Efficacy was assessed using the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria 9, the Disease Activity Score in 28 joints using the C‐reactive protein level (DAS28‐CRP), the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) disability index (DI) 10, and the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI). The PASI scores the severity of psoriasis on 4 regions (head, trunk, upper extremities, and lower extremities) on a scale of 0–72, with lower scores indicating less severe disease 11. Improvement in PASI ≥75% (PASI75) is generally considered to be clinically meaningful, and is a commonly used end point in trials of moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis 12. The proportions of patients with 20%/50%/70% improvement in ACR criteria (ACR20/50/70), a good or moderate DAS28‐CRP response 13, DAS28‐CRP remission (score <2.6), and improvement in HAQ DI ≥0.30 were determined through week 100. PASI75 and PASI90 were assessed for patients with ≥3% body surface area (BSA) affected by psoriasis at baseline.

Dactylitis was assessed in hands and feet using a scoring system of 0–3 (0 = no dactylitis, 1 = mild dactylitis, 2 = moderate dactylitis, and 3 = severe dactylitis), as previously described 14, 15. Enthesitis was assessed using the Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesitis Score 16, modified for PsA (includes insertion of the plantar fascia). HRQOL was evaluated using the Short Form 36 (SF‐36) health survey 11 physical and mental component summary (PCS and MCS, respectively) scores and the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), a 10‐item questionnaire (0–30 points) assessing the effect of skin disease on daily activities, leisure, work/school, and personal relationships (lower scores indicate less impairment) 17.

Radiographic progression was scored using the modified Sharp/van der Heijde score (SHS) with modifications for PsA, including the addition of the distal interphalangeal joints in both hands and the assessment of pencil‐in‐cup and gross osteolysis features (maximum score = 528) 8, 18. Scores from radiographs of the hands and feet (weeks 0, 24, 52, and 100) were averaged from 2 independent readers, or an adjudicator if required 8, blinded to time point, patient identity, and treatment assignment. Through week 52, radiographic data from PSUMMIT 1 were combined with data from PSUMMIT 2 in a prespecified integrated analysis 8. The current analysis includes only data from PSUMMIT 1 from radiographs at weeks 0, 52, and 100; radiographs from weeks 0 and 52 were re‐read as specified in the protocol.

Safety assessments were performed through week 108. Serum samples were collected through week 88 for measurement of serum ustekinumab concentrations, and through week 108 for evaluation of antibodies to ustekinumab.

Statistical analysis

Efficacy end points were analyzed by randomized treatment group using treatment failure rules that were previously applied through week 52 7. Briefly, for clinical efficacy and HRQOL analyses, patients who discontinued treatment due to lack of efficacy or an adverse event (AE) of worsening of disease, or initiated treatment with prohibited medications, were classified as nonresponders for binary end points and assigned zero change for continuous variables at subsequent time points. DMARDs, other than MTX, systemic immunosuppressives, or additional corticosteroids were not considered to be prohibited therapies after week 52. No treatment group comparisons were performed after week 24. In the placebo crossover group, only ustekinumab‐treated patients were included in efficacy analyses after week 24.

Missing radiographic scores between week 52 and 100 were imputed using linear extrapolation if the patient had scores at 2 time points from week 52 to 100. Otherwise, the missing value was replaced with the median of the change in the total scores from all patients within the same MTX stratification at the missing time point.

Subgroup analyses explored efficacy by early escape status, weight group (≤ or >100 kg), and baseline MTX use (yes/no). A post hoc analysis evaluated efficacy outcomes among ACR20 nonresponders at week 100.

Safety analyses included data through week 108 for all patients who received ≥1 study agent administration. AEs were reported by randomized treatment group, and the incidence rate per 100 patient‐years for select AEs of interest were reported by actual treatment received (ustekinumab 45 mg or 90 mg).

RESULTS

Patient disposition

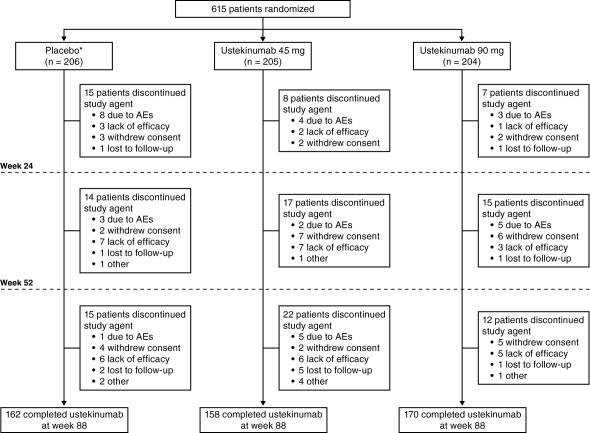

A total of 615 patients were randomized to placebo (n = 206), ustekinumab 45 mg (n = 205), or ustekinumab 90 mg (n = 204); baseline demographics and disease characteristics were well‐balanced among the groups 7. At week 16, 58 patients in the placebo group, 36 in the 45‐mg group, and 26 patients in the 90‐mg group met the early escape criteria. After week 52, 36 patients (7.3%) initiated DMARDS, corticosteroids, or MTX or increased baseline doses of corticosteroids or MTX. Through week 88, 125 patients (20.3%) discontinued the study agent (31 [5.0%] due to AEs; 40 [6.5%] due to lack of efficacy) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient disposition through week 108. ∗ = patients randomized to receive placebo at baseline crossed over to ustekinumab 45 mg at week 16 (early escape) or week 24 (pre‐specified crossover); AEs = adverse events.

Clinical efficacy

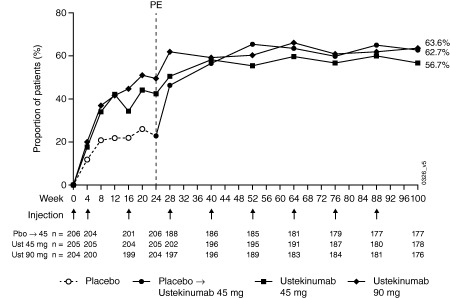

At week 100, 62.7% of patients in the placebo crossover group, 56.7% in the 45‐mg group, and 63.6% in the 90‐mg group had an ACR20 response (Table 1). After placebo crossover at week 24, the proportion of patients with an ACR20 response continued to improve and was sustained through week 100 (Figure 2). ACR50 and ACR70 responses followed a similar pattern and ranged from 37.3–46.0% and 18.6–24.7%, respectively, at week 100 (Table 1). The proportions of patients with either a DAS28‐CRP response or remission were maintained from week 52 7 to week 100 (Table 1). In all 3 groups, the proportions of patients with an ACR20/50/70, DAS28‐CRP response, DAS28‐CRP remission, or PASI75 at week 100 were greater among patients who did not qualify for early escape than for those who met early escape criteria (see Supplementary Table 1, available on the Arthritis Care & Research web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.22645/abstract). Although early escape patients generally had lower response rates, notable proportions of these patients had an ACR20, DAS28‐CRP, or PASI75 response.

Table 1.

Clinical efficacy and radiographic results at week 100a

| Placebo to ustekinumab 45 mgb | Ustekinumab | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45 mg | 90 mg | Combined | ||

| Patients randomized, no. | 189 | 205 | 204 | 409 |

| Clinical efficacy at week 100 | ||||

| Patients, no. | 177 | 178 | 176 | 354 |

| ACR20 | 111 (62.7) | 101 (56.7) | 112 (63.6) | 213 (60.2) |

| ACR50 | 66 (37.3) | 69 (38.8) | 81 (46.0) | 150 (42.4) |

| ACR70 | 33 (18.6) | 44 (24.7) | 39 (22.2) | 83 (23.4) |

| ACR response by baseline weight, no./total no. (%) | ||||

| ACR20 | ||||

| ≤100 kg | 88/134 (65.7) | 83/135 (61.5) | 87/137 (63.5) | 170/272 (62.5) |

| >100 kg | 23/43 (53.5) | 18/43 (41.9) | 25/39 (64.1) | 43/82 (52.4) |

| ACR50 | ||||

| ≤100 kg | 50/134 (37.3) | 55/135 (40.7) | 65/137 (47.4) | 120/272 (44.1) |

| >100 kg | 16/43 (37.2) | 14/43 (32.6) | 16/39 (41.0) | 30/82 (36.6) |

| ACR70 | ||||

| ≤100 kg | 29/134 (21.6) | 36/135 (26.7) | 32/137 (23.4) | 68/272 (25.0) |

| >100 kg | 4/43 (9.3) | 8/43 (18.6) | 7/39 (17.9) | 15/82 (18.3) |

| ACR response by baseline MTX use, no./total no. (%) | ||||

| ACR20 | ||||

| Yes | 57/85 (67.1) | 46/86 (53.5) | 52/87 (59.8) | 98/173 (56.6) |

| No | 54/92 (58.7) | 55/92 (59.8) | 60/89 (67.4) | 115/181 (63.5) |

| ACR50 | ||||

| Yes | 29/85 (34.1) | 30/86 (34.9) | 35/87 (40.2) | 65/173 (37.6) |

| No | 37/92 (40.2) | 39/92 (42.4) | 46/89 (51.7) | 85/181 (47.0) |

| ACR70 | ||||

| Yes | 12/85 (14.1) | 19/86 (22.1) | 13/87 (14.9) | 32/173 (18.5) |

| No | 21/92 (22.8) | 25/92 (27.2) | 26/89 (29.2) | 51/181 (28.2) |

| DAS28‐CRP | ||||

| Good/moderate response | 130 (73.4) | 128 (71.9) | 135 (76.7) | 263 (74.3) |

| Remission | 55 (31.1) | 60 (33.7) | 61 (34.7) | 121 (34.2) |

| HAQ DI | ||||

| Change from baseline, median (IQR) | −0.38 (−0.63, 0.00) | −0.25 (−0.75, 0.00) | −0.38 (−0.81, 0.00) | −0.25 (−0.75, 0.00) |

| Patients with improvement ≥0.3 | 89 (50.3) | 85 (47.8) | 91 (51.7) | 176 (49.7) |

| Patients with ≥3% BSA at baseline, no. | 136 | 145 | 149 | 294 |

| PASI ≤3 at week 100, no./total no. (%)c | 91/122 (74.6) | 83/120 (69.2) | 99/129 (76.7) | 182/249 (73.1) |

| PASI75, no./total no. (%)c | 78/122 (63.9) | 87/120 (72.5) | 92/129 (71.3) | 179/249 (71.9) |

| PASI90, no./total no. (%)c | 50/122 (41.0) | 61/120 (50.8) | 67/129 (51.9) | 128/249 (51.4) |

| PASI response by baseline weight, no./total no. (%)c | ||||

| PASI75 | ||||

| ≤100 kg | 54/91 (59.3) | 71/90 (78.9) | 75/98 (76.5) | 146/188 (77.7) |

| >100 kg | 24/31 (77.4) | 16/30 (53.3) | 17/31 (54.8) | 33/61 (54.1) |

| PASI90 | ||||

| ≤100 kg | 40/91 (44.0) | 49/90 (54.4) | 52/98 (53.1) | 101/188 (53.7) |

| >100 kg | 10/31 (32.3) | 12/30 (40.0) | 15/31 (48.4) | 27/61 (44.3) |

| PASI response by baseline MTX use, no./total no. (%)c | ||||

| PASI75 | ||||

| Yes | 37/59 (62.7) | 40/55 (72.7) | 40/60 (66.7) | 80/115 (69.6) |

| No | 41/63 (65.1) | 47/65 (72.3) | 52/69 (75.4) | 99/134 (73.9) |

| PASI90 | ||||

| Yes | 25/59 (42.4) | 29/55 (52.7) | 27/60 (45.0) | 56/115 (48.7) |

| No | 25/63 (39.7) | 32/65 (49.2) | 40/69 (58.0) | 72/134 (53.7) |

| Dactylitis | ||||

| Patients with dactylitis at baseline, no. | 87 | 101 | 99 | 200 |

| Dactylitis score at baseline, median (IQR) | 5.0 (2.0, 10.0) | 4.0 (2.0, 9.0) | 4.0 (2.0, 11.0) | 4.0 (2.0, 11.0) |

| Week 100 | ||||

| No. | 84 | 90 | 86 | 176 |

| Score improvement, baseline to week 100, median (IQR) | 3.0 (1.0, 7.0) | 3.0 (1.0, 6.0) | 3.0 (1.0, 8.0) | 3.0 (1.0, 6.5) |

| Percent improvement, baseline to week 100, median (IQR) | 100.0 (32.2, 100.0) | 100.0 (66.7, 100.0) | 100.0 (60.0, 100.0) | 100.0 (65.5, 100.0) |

| Patients with ≥1 dactylitis digit at week 100 | 31 (36.9) | 29 (32.2) | 27 (31.4) | 56 (31.8) |

| Enthesitis | ||||

| Patients with enthesitis at baseline, no. | 128 | 142 | 154 | 296 |

| Enthesitis score at baseline, median (IQR) | 4.0 (2.0, 8.0) | 4.0 (2.0, 7.0) | 5.0 (2.0, 8.0) | 4.0 (2.0, 8.0) |

| Week 100 | ||||

| No. | 118 | 119 | 130 | 249 |

| Score improvement, baseline to week 100, median (IQR) | 2.0 (0.0, 5.0) | 2.0 (1.0, 4.0) | 3.0 (0.0, 5.0) | 3.0 (1.0, 5.0) |

| Percent improvement, baseline to week 100, median (IQR) | 87.1 (0.0, 100.0) | 100.0 (9.1, 100.0) | 100.0 (0.0, 100.0) | 100.0 (9.1, 100.0) |

| Patients with enthesitis at week 100 | 62 (52.5) | 58 (48.7) | 61 (46.9) | 119 (47.8) |

| Radiographic progressiond | ||||

| Change from baseline to week 52 in PsA‐modified total SHS score | ||||

| No. | 189 | 205 | 204 | 409 |

| Mean ± SD | 1.49 ± 8.18 | 0.48 ± 2.47 | 0.55 ± 2.97 | 0.51 ± 2.73 |

| Median (IQR) | 0.00 (0.00, 1.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 1.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 1.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 1.00) |

| Change from baseline to week 100 in PsA‐modified total SHS score | ||||

| No. | 189 | 205 | 204 | 409 |

| Mean ± SD | 2.26 ± 12.58 | 0.95 ± 3.82 | 1.18 ± 5.05 | 1.07 ± 4.47 |

| Median (IQR) | 0.00 (0.00, 1.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 1.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 1.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 1.00) |

| Mean ± SD change from baseline to week 100 by weight group and MTX use: | ||||

| Weight | ||||

| ≤100 kg | 2.87 ± 14.39 | 1.09 ± 4.25 | 1.33 ± 5.41 | 1.21 ± 4.86 |

| >100 kg | 0.40 ± 2.65 | 0.54 ± 2.05 | 0.73 ± 3.77 | 0.63 ± 3.01 |

| MTX use | ||||

| Yes | 1.45 ± 5.57 | 0.99 ± 3.76 | 1.54 ± 5.69 | 1.27 ± 4.83 |

| No | 3.00 ± 16.56 | 0.91 ± 3.89 | 0.82 ± 4.32 | 0.86 ± 4.09 |

| Patients with change from baseline in PsA‐modified total SHS score ≤0 | 116 (61.4) | 133 (64.9) | 137 (67.2) | 270 (66.0) |

Values are the number (percentage) unless indicated otherwise. ACR20/50/70 = American College of Rheumatology criteria for 20%/50%/70% improvement; MTX = methotrexate; DAS28 = Disease Activity Score in 28 joints; CRP = C‐reactive protein; HAQ DI = Health Assessment Questionnaire disability index; IQR = interquartile range; BSA = body surface area; PASI75/90 = at least 75%/90% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score; PsA = psoriatic arthritis; SHS = modified Sharp/van der Heijde score.

Patients in the placebo group who did not receive ustekinumab were excluded.

Among patients with ≥3 BSA affected at baseline.

Radiographic results from reading session 2, which included radiographs from weeks 0, 52, and 100.

Figure 2.

Proportion of patients achieving American College of Rheumatology criteria for 20% improvement responses over time through week 100. PE = primary end point; Pbo = placebo; Ust = ustekinumab.

Among patients with dactylitis at baseline, median baseline dactylitis scores were 5.0 in the placebo group and 4.0 in both ustekinumab groups (Table 1). At week 100, the 3 treatment groups all had a median score improvement of 3.0 and a median percent improvement of 100% (Table 1). In the combined ustekinumab group, the proportions of patients with ≥1 digit with residual dactylitis continued to decrease from week 52 (42.6%; data not shown) through week 100 (31.8%; Table 1). Among patients with enthesitis at baseline, median baseline enthesitis scores were 4.0 in the placebo and ustekinumab 45‐mg groups and 5.0 in the ustekinumab 90‐mg group (Table 1). At week 100, the median score improvement and percent improvement from baseline, respectively, were 2.0 and 87.1% in the placebo crossover group, 2.0 and 100% in the 45‐mg group, and 3.0 and 100% in the 90‐mg group (Table 1). The proportions of patients with residual enthesitis also continued to decrease from week 52 (55.1%; data not shown) through week 100 (47.8%; Table 1).

Of the 615 randomized patients, 440 (71.7%) had ≥3% BSA affected by psoriasis at baseline 7. At week 100, 63.9%, 72.5%, and 71.3% in the placebo crossover, 45‐mg, and 90‐mg groups, respectively, had a PASI75 response, and 41.0%, 50.8%, and 51.9%, respectively, had a PASI90 response (Table 1). In addition, the vast majority of patients (69.2–76.7%) had a PASI score ≤3 at week 100 (Table 1).

ACR20/50/70 and PASI75/90 response rates at week 100 were also evaluated by baseline patient weight (≤ or >100 kg) and MTX use (yes/no) (Table 1). Within each weight group, the proportions of ACR and PASI responders were maintained over time, and in general, response rates were numerically greater for patients ≤100 kg than for patients >100 kg. At week 100, ACR20/50/70 and PASI75/90 response rates were similar between the dose groups for patients ≤100 kg; however, among patients >100 kg, response rates were generally higher for patients in the 90‐mg group than in the 45‐mg group. In a post hoc analysis by weight group and early escape status (yes/no), patients >100 kg tended to have higher ACR and PASI response rates with the 90‐mg dose than with the 45‐mg dose, which was consistent with the overall population. It should be noted that the relatively small numbers of patients in the subgroups limit the interpretation of these post hoc analysis results (Supplementary Table 2, available on the Arthritis Care & Research web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.22645/abstract).

ACR20/50/70 response rates at week 100 were numerically higher among patients who were not receiving MTX at baseline than among patients receiving MTX in the same treatment group (Table 1). A similar trend was observed for PASI75 and PASI90 responders at week 100 in the 90‐mg group; however, no consistent pattern in PASI response was observed with regard to baseline MTX use in the 45‐mg group.

Improvements from baseline in physical function and HRQOL were also sustained over time with median decreases in HAQ DI scores from baseline to week 100 of 0.38, 0.25, and 0.38 in the placebo crossover, 45‐mg, and 90‐mg groups, respectively (Table 1), and approximately half of all patients in each group had an improvement in HAQ DI ≥0.30 at week 100. Median changes from baseline to week 100 in SF‐36 PCS and MCS scores ranged from 4.8–6.4 and from 3.0–3.7, respectively, and median changes from baseline in DLQI score at week 100 were −6.0 in the placebo crossover group, −5.0 in the 45‐mg group, and −6.0 in the 90‐mg group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Changes from baseline to week 100 in health‐related quality of life measuresa

| Placebo to ustekinumab 45 mgb | Ustekinumab | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45 mg | 90 mg | Combined | ||

| Patients randomized, no. | 189 | 205 | 204 | 409 |

| Change from baseline to week 100 | ||||

| SF‐36 PCS score | 4.8 (0.0, 12.7) | 5.1 (0.0, 13.7) | 6.4 (0.0, 14.2) | 5.3 (0.0, 14.1) |

| SF‐36 MCS score | 3.3 (0.0, 11.6) | 3.0 (−1.0, 9.3) | 3.7 (−0.6, 10.7) | 3.2 (−0.8, 9.9) |

| DLQI score | −6.0 (−11.0, −1.0) | −5.0 (−11.5, −1.0) | −6.0 (−11.0, −2.0) | −5.0 (−11.0, −2.0) |

Values are the median (interquartile range) unless indicated otherwise. SF‐36 = Short Form 36 health survey; PCS = physical component summary; MCS = mental component summary; DLQI = Dermatology Life Quality Index.

Patients in the placebo group who did not receive ustekinumab were excluded.

In a post hoc analysis of ACR20 nonresponders at week 100, improvements were observed in skin, soft tissues, physical function, and HRQOL; however, the magnitude of improvement was generally lower than that observed in the overall study population (Supplementary Table 3, available on the Arthritis Care & Research web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.22645/abstract).

Radiographic progression

Radiographic progression through week 100 of PSUMMIT 1 was analyzed using data from a second reading session of weeks 0, 52, and 100. This analysis included only patients who received ustekinumab therapy; therefore, 17 patients who received only placebo were not included.

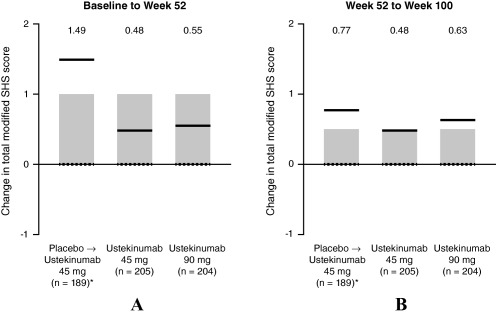

The median changes from baseline in total SHS score at weeks 52 and 100 were 0.0 for all 3 treatment groups (Table 1). Mean changes from baseline to week 52 in total SHS score were 0.48 in the 45‐mg group and 0.55 in the 90‐mg group, and mean changes from baseline to week 100 were 0.95 and 1.18, respectively (Table 1). At both time points, mean changes were numerically lower in the ustekinumab groups than in the placebo crossover group. In the ustekinumab groups, mean changes in total SHS score from week 52 to week 100 were similar to those from baseline to week 52 (Figure 3). However, in the placebo crossover group, mean change from week 52 to 100 in total SHS score was numerically lower than the change from baseline to week 52 (Figure 3). No consistent pattern was observed for changes in total SHS score when analyzed by early‐escape status (Supplementary Table 1, available on the Arthritis Care & Research web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.22645/abstract).

Figure 3.

Mean change in psoriatic arthritis–modified total Sharp/van der Heijde score (SHS) from week 0 to week 52 (A), and from week 52 to week 100 (B), showing interquartile ranges (shaded bars), means (solid line), and medians (broken lines). Mean values presented above graphs for each group. ∗ = patients who met early escape criteria at week 16 or crossed over to ustekinumab 45 mg at week 24.

The median change from baseline to week 100 in total SHS score was 0, regardless of baseline weight group or MTX use (data not shown), consistent with results of the overall population. Mean changes from baseline in total SHS score were generally smaller for patients >100 kg than for those ≤100 kg (Table 1). Radiographic progression did not appear to be influenced by baseline MTX use (Table 1).

Spondylitis was evaluated through week 24 using the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI), and significantly greater proportions of ustekinumab‐treated patients had improvements in BASDAI score at week 24 versus placebo 7. However, no additional data on axial manifestations were collected after week 24.

Adverse events

Through week 108, a total of 598 patients received ≥1 ustekinumab injections, and 23 patients (3.8%) discontinued ustekinumab due to an AE (Table 3). Overall, the types and rates of AEs through week 108 did not indicate any disproportional rate increase compared with week 52 7. Infections were the most frequent AEs for ustekinumab‐treated patients through week 108 (43.3%); the most common being nasopharyngitis (n = 70, 11.7%, 10.41 per 100 patient‐years [95% confidence interval (95% CI)] 8.56, 12.55) and upper respiratory tract infection (n = 60, 10.0%, 7.48 per 100 patient‐years [95% CI 5.92, 9.32]). AEs through week 108 were not affected by baseline concomitant MTX use (data not shown). There were no reports of anaphylactic shock, serum sickness–like reactions, or deaths.

Table 3.

Adverse events (AEs) through week 108a

| Placebo to 45 mgb | Ustekinumab 45 mgc | Ustekinumab 90 mg | All ustekinumab | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients treated with ustekinumab, no. | 189 | 205 | 204 | 598 |

| Mean duration of followup, no. weeks | 79.9 | 96.8 | 98.0 | 91.9 |

| Patients with ≥1 AE | 117 (61.9) | 158 (77.1) | 148 (72.5) | 423 (70.7) |

| Infections | 66 (34.9) | 93 (45.4) | 100 (49.0) | 259 (43.3) |

| Patients who discontinued due to AEs | 4 (2.1) | 11 (5.4) | 8 (3.9) | 23 (3.8) |

| Common (≥5%) AEs | ||||

| Nasopharyngitis | 15 (7.9) | 25 (12.2) | 30 (14.7) | 70 (11.7) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 18 (9.5) | 22 (10.7) | 20 (9.8) | 60 (10.0) |

| Hypertension | 9 (4.8) | 15 (7.3) | 17 (8.3) | 41 (6.9) |

| Arthralgia | 9 (4.8) | 15 (7.3) | 15 (7.4) | 39 (6.5) |

| Psoriatic arthropathy | 10 (5.3) | 8 (3.9) | 14 (6.9) | 32 (5.4) |

| Patients with ≥1 SAE | 15 (7.9) | 26 (12.7) | 17 (8.3) | 58 (9.7) |

| AEs of interest | ||||

| Patients with ≥1 serious infection | 1 (0.5) | 5 (2.4) | 5 (2.5) | 11 (1.8) |

| Patients with ≥1 MACE | 2 (1.1) | 4 (2.0) | 1 (0.5) | 7 (1.2) |

| Malignancies | ||||

| B cell lymphoma | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 1 (0.2) |

| Basal cell carcinoma | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) |

| Renal cell carcinoma | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.2) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) |

| Deaths | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Values are the number (percentage) unless indicated otherwise. SAE = serious AE; MACE = major adverse cardiovascular event.

Includes all patients who received at least 1 injection of ustekinumab after early escape at week 16 or crossover at week 24.

Includes all patients randomized to the 45‐mg group, including those who early escaped at week 16 to receive ustekinumab 90 mg.

Among all ustekinumab‐treated patients, 58 (9.7%) had ≥1 serious AE (SAE) through week 108. Most were singular events, with the exceptions of myocardial infarction (n = 5), osteoarthritis (n = 3), cholecystitis/cholecystitis acute (n = 3), dehydration (n = 2), and depression (n = 2). The proportion of patients with ≥1 serious infection was low (45‐mg group, 2.4%; 90‐mg group, 2.5%) (Table 3); the incidence (95% CI) of serious infections per 100 patient‐years was 0.64 (0.18, 1.64) among patients receiving ustekinumab 45 mg and 2.30 (1.10, 4.24) among those receiving ustekinumab 90 mg. The higher rate reported in the 90‐mg group was mainly driven by 2 patients who reported multiple events. No serious opportunistic infections or cases of active tuberculosis occurred.

Through week 108, 7 events were reported as major adverse cardiovascular events (incidence per 100 patient‐years [95% CI] for 45‐mg group: 0.96 [0.35, 2.10]; for 90‐mg group: 0.23 [0.01, 1.28]). Three (nonfatal stroke: n = 1; myocardial infarction: n = 2) occurred before week 52 7. After week 52, myocardial infarction occurred in 3 patients (45 mg: n = 1; 90 mg: n = 1; 45 mg to 90 mg: n = 1), and 1 patient (45 mg) had an ischemic stroke. All patients who experienced a major adverse cardiovascular event had ≥2 cardiovascular risk factors other than PsA (i.e., obesity, history of smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, or previous stroke).

Four malignancies were reported. The incidence (95% CI) of total malignancies per 100 patient‐years was 0.32 (0.04, 1.16) for patients receiving ustekinumab 45 mg, and 0.46 (0.06, 1.67) for patients receiving ustekinumab 90 mg. One patient (45‐mg group) was diagnosed with B cell lymphoma and discontinued study treatment. Another patient (placebo to 45 mg) was diagnosed with renal cell carcinoma approximately 11 weeks after the week‐88 ustekinumab administration. Two patients were diagnosed with nonmelanoma skin cancer (both receiving 90 mg): squamous cell carcinoma in one patient approximately 11 weeks after the week‐88 ustekinumab administration and basal cell carcinoma in another patient at week 88.

A total of 4,618 ustekinumab injections (45 mg: n = 2,743; 90 mg: n = 1,875) were administered, and 17 (total 0.4%; 45 mg: 4 [0.1%]; 90 mg: 13 [0.7%]) were associated with an injection site reaction. All injection site reactions were mild, and none resulted in treatment discontinuation.

No clear pattern of changes in hematology parameters or other laboratory measurements over time was discerned for any treatment group. The proportions of patients with markedly abnormal post‐baseline values were generally low and comparable between the ustekinumab doses.

Pharmacokinetics and immunogenicity

Serum ustekinumab concentrations increased in a dose‐proportional manner. At week 88, the mean steady‐state trough serum ustekinumab concentration was 0.56 μg/ml among patients in the 45‐mg group who did not enter early escape and 1.02 μg/ml among patients in the 90‐mg group, a difference of approximately 2 fold. Serum ustekinumab concentrations tended to be lower among patients >100 kg than in patients ≤100 kg.

Through week 108, a total of 49 of 591 patients (8.3%) tested positive for antibodies to ustekinumab. The incidence of antibodies to ustekinumab was similar between the 2 doses, but was lower among patients receiving concomitant MTX (n = 13 of 287, 4.5%) compared with those not receiving MTX (n = 36 of 304, 11.8%). Patients who tested positive for antibodies to ustekinumab had lower mean serum ustekinumab concentrations than patients who tested negative. The proportions of patients with an ACR20 or ACR50 response tended to be numerically lower for patients who were positive for antibodies to ustekinumab compared with those who were negative (Supplementary Table 4, available on the Arthritis Care & Research web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.22645/abstract); similar results were observed for PASI75 and PASI90 (Supplementary Table 5).

DISCUSSION

The PSUMMIT 1 study was a phase 3, double‐blind placebo‐controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of ustekinumab treatment through 2 years in adult patients with active PsA, despite prior DMARD or NSAID therapy. Through the placebo‐controlled period of PSUMMIT 1 (weeks 0–24), ustekinumab‐treated patients had significantly greater reductions in the clinical signs and symptoms of both joint and skin disease, greater improvements in physical function, and less radiographic progression when compared with those receiving placebo 7, 8. These responses were maintained through 1 year 7, 8, and the current analyses further demonstrate the maintenance of improvements in clinical efficacy and radiographic measures through 2 years of treatment with ustekinumab.

Approximately 20% of patients discontinued treatment prior to week 88, which was comparable to discontinuation rates for trials of other biologic therapies 19, 20. At week 100, a high level of response was observed across the treatment groups for both joint and skin disease activity measures (ACR20/50/70 ranges: 57–64%, 37–46%, and 19–25%, respectively, and PASI75/90 ranges: 64–73% and 41–52%, respectively). Improvements in dactylitis, enthesitis, physical function, and HRQOL were also maintained through week 100. Early‐escape patients consistently had lower response rates than patients in the same treatment group who did not meet the early escape criteria. Despite this, modest proportions of these patients experienced clinically meaningful improvements for some outcomes.

As noted previously, the time to reach a maximum ACR response may be longer with ustekinumab than with anti‐TNF therapies, but in general, the proportions of patients reaching an ACR response at week 52 of the PSUMMIT 1 trial were consistent with those observed with anti‐TNF agents 7. In a head‐to‐head psoriasis clinical study, ustekinumab demonstrated superior efficacy in achieving PASI responses compared with etanercept during the first 12 weeks of treatment 21. The current analysis further indicated that the proportions of patients who were ACR20/50/70 responders or PASI75/90 responders at week 100 also appeared to be consistent with results from trials of anti‐TNF therapies in PsA 19, 20.

Patients who did not have an ACR20 response at week 100 generally experienced meaningful improvements in skin, dactylitis, enthesitis, physical function, and HRQOL outcomes at week 100. Approximately 50% had ≥3% BSA with psoriasis involvement at baseline; therefore, skin improvement alone cannot fully explain their study continuation. The totality of improvements observed in these outcomes, along with some improvements in tender and swollen joint counts that did not exceed the 20% threshold for both at individual visits, may help explain why these patients remained in the trial and continued ustekinumab treatment through 2 years.

In the current analysis of patients from PSUMMIT 1, a biologic‐naive population, inhibition of structural damage with ustekinumab therapy was maintained through week 108. In the 45‐mg and 90‐mg groups, radiographic progression was similar from baseline to week 52 and from week 52 to week 100, indicating that inhibition of radiographic progression through week 52 was maintained from week 52 to 100. Additionally, mean changes from baseline through week 100 in both the 45‐mg and 90‐mg groups were less than or comparable to the mean change in the placebo group observed during the placebo‐controlled period (weeks 0–24) 8, further supporting the inhibition effect during the second year of treatment.

Throughout the trial, patients ≤100 kg at baseline generally had numerically greater ACR and PASI response rates than did patients >100 kg receiving the same dose; among patients >100 kg, response rates were higher in the 90‐mg group than in the 45‐mg group. In the radiographic analysis, patients >100 kg generally had less progression than did those ≤100 kg, consistent with previous research showing an association of high body mass index with less radiographic progression among patients with rheumatoid arthritis 22. Ustekinumab was efficacious irrespective of MTX use, although the proportions of patients with an ACR20/50/70 response tended to be numerically greater among patients not receiving baseline MTX compared with those receiving MTX. No consistent pattern was observed from similar analyses of PASI responses. However, as is the case with most recent PsA studies, the study design does inform as to whether combination therapy with MTX may be of benefit, and if so, to what extent and for which outcomes.

Safety findings through week 108 were consistent with those observed through week 52 7, and the known safety profile of ustekinumab in patients with psoriasis 23. There was no apparent dose effect for the rates and types of AEs or SAEs. All injection site reactions were mild, and none led to study discontinuation. The incidence of serious infections was low and similar across treatment groups. Eleven patients (1.8%) had a serious infection, and there was no apparent increase in incidence with longer ustekinumab exposure. There were no cases of active tuberculosis or serious opportunistic infections.

Seven major adverse cardiovascular events occurred, all in patients with ≥2 preexisting cardiovascular risk factors. In addition, 4 malignancies were reported. Ustekinumab treatment did not appear to affect hematology or chemistry laboratory values. There were no anaphylactic reactions, serum sickness–like reactions, or deaths. No apparent effect of concomitant MTX use on AEs was observed.

Approximately 8% of ustekinumab‐treated patients were positive for antibodies to ustekinumab, with a lower incidence among patients receiving concomitant MTX compared with those not receiving MTX. In both dose groups, mean serum ustekinumab concentrations were lower in patients who tested positive for antibodies to ustekinumab than in patients who tested negative. Patients who tested positive for antibodies to ustekinumab tended to have lower ACR response rates; however, the presence of these antibodies did not preclude a clinical response to ustekinumab, consistent with a previous analysis 24.

Interpretation of the findings through week 108 of PSUMMIT 1 is limited by the lack of a placebo control group after week 24. Although ACR response rates seemed higher in patients not receiving MTX at baseline versus those receiving MTX, this trial was not designed to assess such differences. Furthermore, efficacy for patients who early escaped from 45 mg to 90 mg was analyzed within the 45‐mg group through week 88, which may have undermined the dose responses observed between the dose groups.

In summary, these results demonstrated the maintenance of the effects of ustekinumab 45 mg and 90 mg every 12 weeks on clinical efficacy, radiographic progression, and HRQOL through 2 years, with no unexpected AEs. This study demonstrated a favorable benefit risk profile of ustekinumab treatment in patients with active PsA.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be submitted for publication. Dr. Kavanaugh had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study conception and design

Kavanaugh, Puig, Gottlieb, Ritchlin, Li, Wang, Mendelsohn, Song, Zhu, McInnes.

Acquisition of data

Kavanaugh, Gottlieb, Ritchlin, Li, Wang, Mendelsohn, Song, Zhu, McInnes.

Analysis and interpretation of data

Kavanaugh, Puig, Gottlieb, Ritchlin, Li, Wang, Mendelsohn, Song, Zhu, Rahman, McInnes.

ROLE OF THE STUDY SPONSOR

Authors who are current or former employees of Janssen Research & Development, LLC were involved in the study design and in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, the writing of the manuscript, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. All authors approved the manuscript for submission. Yin You, PhD, of Janssen Research & Development, LLC, provided statistical support, and Rebecca Clemente, PhD, and Mary Whitman, PhD, of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, provided writing support.

Supporting information

Supplementary Table 1. Efficacy at week 100 by early escape status.

Supplementary Table 2. Efficacy at week 100 by weight group and early escape status.

Supplementary Table 3. Efficacy at week 100 for ACR20 nonresponders.

Supplementary Table 4. Effect of antibody‐to‐ustekinumab status through week 108 on ACR20 and ACR50 responses at week 88.

Supplementary Table 5. Effect of antibody‐to‐ustekinumab status through week 108 on PASI75 and PASI90 responses at week 88.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01009086.

REFERENCES

- 1. Leonard DG, O'Duffy JD, Rogers RS. Prospective analysis of psoriatic arthritis in patients hospitalized for psoriasis. Mayo Clin Proc 1978;53:511–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shbeeb M, Uramoto KM, Gibson LE, O'Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. The epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, USA, 1982–1991. J Rheumatol 2000;27:1247–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gladman DD, Antoni C, Mease P, Clegg DO, Nash P. Psoriatic arthritis: epidemiology, clinical features, course, and outcome. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;Suppl 2:ii14–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Puig L, Strohal R, Husni ME, Tsai TF, Noppakun N, Szumski A, et al. Cardiometabolic profile, clinical features, quality of life and treatment outcomes in patients with moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. J Dermatolog Treat 2015;26:7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lee E, Trepicchio WL, Oestreicher JL, Pittman D, Wang F, Chamian F, et al. Increased expression of interleukin 23 p19 and p40 in lesional skin of patients with psoriasis vulgaris. J Exp Med 2004;199:125–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stelara: package insert. Horsham (PA): Janssen Biotech; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7. McInnes IB, Kavanaugh A, Gottlieb AB, Puig L, Rahman P, Ritchlin C, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: 1 year results of the phase 3, multicentre, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled PSUMMIT 1 trial. Lancet 2013;382:780–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kavanaugh A, Ritchlin C, Rahman P, Puig L, Gottlieb AB, Li S, et al. Ustekinumab, an anti‐IL‐12/23 p40 monoclonal antibody, inhibits radiographic progression in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: results of an integrated analysis of radiographic data from the phase 3, multicentre, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled PSUMMIT‐1 and PSUMMIT‐2 trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1000–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, Bombardier C, Furst D, Goldsmith C, et al. American College of Rheumatology preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:727–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fries JF, Spitz P, Kraines RG, Holman HR. Measurement of patient outcome in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1980;23:137–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fredriksson T, Pettersson U. Severe psoriasis: oral therapy with a new retinoid. Dermatologica 1978;157:238–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Feldman SR, Krueger GG. Psoriasis assessment tools in clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;Suppl 2:ii65–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Van Riel PL, van Gestel AM, Scott DL. EULAR handbook of clinical assessments in rheumatoid arthritis. Alphen Aan Den Rijn (The Netherlands): Van Zuiden Communications; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Antoni CE, Kavanaugh A, Kirkham B, Tutuncu Z, Burmester GR, Schneider U, et al. Sustained benefits of infliximab therapy for dermatologic and articular manifestations of psoriatic arthritis: results from the infliximab multinational psoriatic arthritis controlled trial (IMPACT). Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:1227–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kavanaugh A, McInnes I, Mease P, Krueger GG, Gladman D, Gomez‐Reino J, et al. Golimumab, a new human tumor necrosis factor α antibody, administered every four weeks as a subcutaneous injection in psoriatic arthritis: twenty‐four–week efficacy and safety results of a randomized, placebo‐controlled study. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:976–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Heuft‐Dorenbosch L, Spoorenberg A, van Tubergen A, Landewe R, van der Tempel H, Mielants H, et al. Assessment of enthesitis in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:127–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol 1994;19:210–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Van der Heijde D, Sharp J, Wassenberg S, Gladman DD. Psoriatic arthritis imaging: a review of scoring methods. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64 Suppl 2:ii61–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kavanaugh A, McInnes IB, Mease PJ, Krueger GG, Gladman DD, van der Heijde D, et al. Clinical efficacy, radiographic and safety findings through 2 years of golimumab treatment in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: results from a long‐term extension of the randomised, placebo‐controlled GO‐REVEAL study. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1777–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mease PJ, Ory P, Sharp JT, Ritchlin CT, van den Bosch F, Wellborne F, et al. Adalimumab for long‐term treatment of psoriatic arthritis: 2‐year data from the Adalimumab Effectiveness in Psoriatic Arthritis Trial (ADEPT). Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:702–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Griffiths CE, Strober BE, van de Kerkhof P, Ho V, Fidelus‐Gort R, Yeilding N, et al. Comparison of ustekinumab and etanercept for moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis. N Engl J Med 2010;362:118–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Westhoff G, Rau R, Zink A. Radiographic joint damage in early rheumatoid arthritis is highly dependent on body mass index. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:3575–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Papp KA, Griffiths CE, Gordon K, Lebwohl M, Szapary PO, Wasfi Y, et al. Long‐term safety of ustekinumab in patients with moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis: final results from 5 years of follow‐up. Br J Dermatol 2013;168:844–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhu Y, Keen M, Gunn G, Schantz A, Li S, Mendelsohn AM, et al. Immunogenicity and clinical relevance of ustekinumab in two phase 3 studies in patients with active psoriatic arthritis. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev 2013;2 Suppl 1:32. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1. Efficacy at week 100 by early escape status.

Supplementary Table 2. Efficacy at week 100 by weight group and early escape status.

Supplementary Table 3. Efficacy at week 100 for ACR20 nonresponders.

Supplementary Table 4. Effect of antibody‐to‐ustekinumab status through week 108 on ACR20 and ACR50 responses at week 88.

Supplementary Table 5. Effect of antibody‐to‐ustekinumab status through week 108 on PASI75 and PASI90 responses at week 88.