Abstract

Background: As aid-in-dying laws are gaining more public acceptance and support, it is important to understand diverse perceptions toward physician-assisted death (PAD). We compare attitudes of residents from California and Hawaii to identify variables that may predict attitudes toward PAD.

Methods: A cross-sectional online survey of 1095 participants (a 75.8% survey completion rate) from California and 819 from Hawaii (a 78.4% survey completion rate). Data were collected between July through October 2015.

Results: Majority of study participants in California (72.5%) and Hawaii (76.5%) were supportive of PAD. Only 36.8% of participants in Hawaii and 34.8% of participants in California reported completing advance directives. To better understand which subgroups were most in favor of PAD, data were analyzed using both recursive partitioning and stepwise logistic regression. Older participants were more supportive of PAD in both states. Also, all ethnic groups were equally supportive of PAD. Completion of advance directives was not a significant predictor of attitudes toward PAD. Persons who reported that faith/religion/spirituality was less important to them were more likely to support PAD in both states. Thus, the major influences on the attitudes to PAD were religious/spiritual views and age, not ethnicity and gender. Even in the subgroups least supportive of PAD, the majority supported PAD.

Conclusions: This study shows that in the ethnically diverse states of California and Hawaii, faith/religion/spirituality and age are major influencers of attitudes toward PAD and not ethnicity and gender. Even in the subgroups least supportive of PAD, the majority supports PAD.

Introduction

Age, ethnicity, and gender influence attitudes1–10 toward physician-assisted death (PAD). Earlier work2–4 has suggested that patients who are more religious, older, ethnic minorities, and/or women were opposed to PAD. Others5–7 found that older Americans are less likely to support legalization of PAD compared to the general population. Attitudes8,9 toward PAD vary in different racial and ethnic groups. One study10 reported that blacks were less likely to envision asking for PAD for themselves and attributed these differences to the strength of religious commitment. Another1 compared a convenience sample of community dwelling older Hispanic Americans (HA) to non-Hispanic whites and found that the HA were more in favor of PAD.

PAD is now legal in Oregon, Washington, Vermont, and, most recently, in California. It has also been legalized in Canada. The California End-of-life Option Act (SB 128),11 modeled after the Oregon law enacted in 1997,2 was passed on October 5th, 2015, and will go into effect on June 9th, 2016. This law will legalize physician aid-in-dying and will allow doctors to prescribe lethal medication if requested by a patient with a terminal illness to end their life.

California is unique12 in two specific ways compared to the other U.S. states that have legalized PAD: (a) it is one of the most populous states in the nation and (b) it is a minority-majority state with tremendous ethnic diversity. In contrast to California, PAD has not been legalized in Hawaii. However, Hawaii is similar to California in being very ethnically diverse. The primary objective of this study was to compare the attitudes of California residents to Hawaii residents toward PAD and to determine if there were specific variables that could potentially predict their attitudes. It is important to note that our study was conducted just as the California legislation was coming to vote in 2015.

Methods

In April 2015, we launched a project to better understand diverse Americans' attitudes toward end-of-life issues. An online survey was developed by one of the authors (V.S.P.) guided by data from our prior studies7,8 and further informed by focus groups and interviews with patients and families from various ethnic groups. It was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Stanford University School of Medicine. In this report, we present analyses of data accrued from all participants who completed the survey online from the states of California and Hawaii. The participants' age, gender, race/ethnicity were recorded (Table 1) along with the answers to the following questions:

a. How important is your faith/religion/spirituality to you? (unimportant, somewhat important, important, and very important)

b. Question from the 2012 Massachusetts Ballot Measure: I think that it is acceptable to allow a physician licensed to prescribe medication, at the request of a terminally-ill patient meeting certain conditions, to end that person's life? (True/False)

c. Have you completed your advance directive? (Yes/No)

Table 1.

Participant Demographic Characteristics and Responses on Key Variables: Importance of Faith/Religion/Spirituality, Attitudes Toward Physician-Assisted Death, Completion of Advance Directives

| Descriptor | California, n = 1095 | Hawaii, n = 819 |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 51.1 (14.8) | 46.1 (17.1) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Female | 575 (52.5) | 530 (64.7) |

| Male | 520 (47.5) | 289 (35.3) |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Black/African American | 109 (10.0) | 16 (2.0) |

| Asian | 214 (19.5) | 386 (47.1) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 349 (31.9) | 33 (4.0) |

| White, not Hispanic/Latino | 422 (38.5) | 307 (37.5) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1 (0.1) | 77 (9.4) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||

| Married | 564 (51.5) | 456 (55.7) |

| Single | 326 (29.8) | 263 (32.1) |

| Divorced | 146 (13.3) | 78 (9.5) |

| Widowed | 59 (5.4) | 22 (2.7) |

| Educational level, n (%) | ||

| No formal education | 3 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Elementary school | 4 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| High school | 213 (19.5) | 104 (12.7) |

| College | 678 (61.9) | 487 (59.5) |

| Graduate professional | 197 (18.0) | 228 (27.8) |

| Importance of faith/religion/spirituality, n (%) | ||

| Unimportant | 202 (18.4) | 169 (20.6) |

| Somewhat important | 213 (19.5) | 211 (25.8) |

| Important | 301 (27.5) | 246 (30.0) |

| Very important | 379 (34.6) | 193 (23.6) |

| Completed advance directives, n (%) | ||

| No | 714 (65.2) | 517 (63.1) |

| Yes | 381 (34.8) | 302 (36.9) |

| Opinion about PAD, n (%) | ||

| Not supportive | 301 (27.5) | 192 (23.4) |

| Supportive | 794 (72.5) | 627 (76.6) |

PAD, physician-assisted death.

Participants

Participants were recruited through an online survey housed and stored on a secure Stanford server with links that were easily accessible through Stanford portals and social media sites. A project manager with computer expertise built and monitored the survey. The questionnaire was administered one time and no personal health identifiers were collected in an effort to promote participant confidentiality and honest responses without concerns about individual scrutiny. The secure online system is programmed to prevent ballot box stuffing so that participants took the survey just once. All questions in the survey were set at “force response,” that is, participants who did not respond to all the questions would be unable to submit their completed survey. The participant state of residence was determined using their reported zip code. The data presented here were collected from July through October 2015. The investigators had no direct contact with the participants.

Data analyses

Data were analyzed using two methods, stepwise forward logistic regression13 and recursive partitioning,14 to identify any predictor in support of PAD. Recursive partitioning was carried out using Quality Receiver Operating Curve (QROC) analysis.14,15 Logistic regression identifies linear predictors, while recursive partitioning identifies statistically different subgroups.15 QROC16 examines each of the values or categories of each input predictor and selects the variable and its cutoff point with the optimal balance (weighted kappa statistic) of sensitivity and specificity for identifying those subjects with the specific outcome of interest (in this case, positive disposition toward PAD). The entire group is then divided into two subgroups—those above and below the selected cutoff point on the selected variable, and the process is reiterated until no further discrimination is achieved. The result is a decision tree. The available predictors in the models included participant demographics (gender, age, race/ethnicity, education, marital status) and importance ascribed to faith/spirituality/religion (0 = not important, 1 = somewhat important, 2 = important, 3 = very important). Analyses were done using the SAS software (SAS 9.3; SAS, Inc.). The data for the two states were analyzed separately (Table 1).

Results

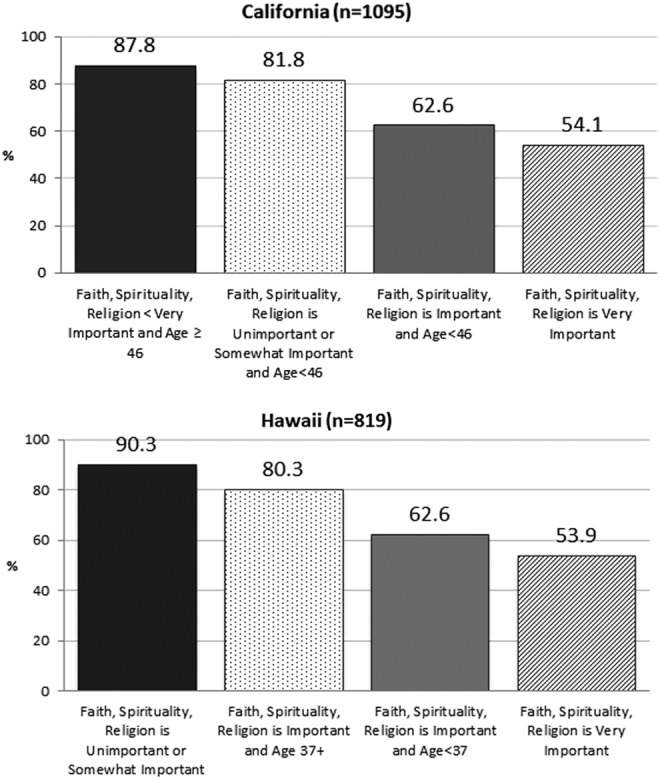

One thousand ninety-five participants (a total of 1444 clicked on the link, 75.8% survey completion rate) from California and 819 (a total of 1045 clicked on the link, 78.4% survey completion rate) from Hawaii (Table 1) completed and submitted the survey. The California and Hawaii cohorts were not significantly different either in their attitudes toward PAD or in advance directive completion rates. The majority of participants from both California (72.5%) and Hawaii (76.5%) were supportive of PAD. To better understand which subgroups were most in favor of PAD (Fig. 1), data were analyzed using both recursive partitioning (Quality Receiver Operating Characteristic) and stepwise forward logistic regression. For both state samples, with support for PAD as the outcome, both the logistic regression and recursive partitioning analyses identified age and level of faith/religion/spirituality as significant predictors. Older participants were more supportive of PAD compared to their younger counterparts in both states. Persons who reported that spirituality was less important to them were more likely to support PAD in both states. All ethnic groups in both California and Hawaii were overall in support of PAD. In California, 75.6% of non-Hispanic whites, 74.3% of Asians, and 71.6% of Hispanics were in support of PAD compared to 59.6% of African Americans. In Hawaii, 77.9% of non-Hispanic whites, 77.5% of Asians, 75.3% of Native Hawaiian /Pacific Islanders, and 63.6% of Hispanics were in support of PAD. Within Asian Americans, Chinese were most favorably disposed toward PAD (82.7% in California and 85.5% in Hawaii), followed by Japanese (74.6% in California and 76.5% in Hawaii) and the Filipino Americans (67.7% in California and 76.5% in Hawaii). It is remarkable that in both states, even participants who were deeply spiritual, a majority of 52%, were still in support of PAD. The effects of gender and ethnicity did not reach statistical significance in terms of attitudes toward PAD. Both genders and all racial/ethnic groups in both states were equally in support of PAD (Table 2). The completion of advance directives was relatively low (34.8% in California and 36.9% in Hawaii cohorts) and higher among those who were older and more highly educated. Completion of advance directives was not a significant predictor of attitudes toward PAD.

FIG. 1.

This figure shows subgroups with different likelihoods of supporting PAD as identified by the recursive partitioning. PAD, physician-assisted death.

Table 2.

Ethnicity/Race of the Participants in Both States: Overall, Non-Hispanic Whites Are Most Supportive of Physician-Assisted Death Followed by Asian Americans, Hispanic Americans, and African Americans

| % Supporting PAD (95% CI) | Total subjects | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | California | Hawaii | California | Hawaii |

| Black/African American | 59.6 (49.8–68.9) | 62.5 (35.4–84.8) | 109 | 16 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 71.6 (66.6–76.3) | 63.6 (45.1–79.6) | 349 | 33 |

| White, not Hispanic/Latino | 75.6 (71.2–79.6) | 77.9 (72.8–82.4) | 422 | 307 |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 100 (2.5–100) | 75.3 (64.2–84.4) | 1 | 77 |

| Asian | 74.3 (67.9–80.0) | 77.5 (73.0–81.5) | 214 | 386 |

| Chinese | 82.7 (72.7–90.2) | 85.5 (76.1–92.3) | 81 | 83 |

| Filipino | 67.7 (48.6–83.3) | 66.7 (52.5–78.9) | 31 | 54 |

| Japanese | 74.6 (61.6–85.0) | 76.5 (70.3–82.0) | 59 | 217 |

| Total | 72.5 (69.8–75.1) | 76.6 (73.5–79.4) | 1095 | 819 |

CI, confidence interval.

Recursive partitioning analyses were done separately for each state to identify subgroups that were more likely to be in support of PAD. Recursive partitioning (Fig. 1) identified the following subgroups: in California, participants who were older than 46 years of age and reported that spirituality was very important were 87.8% in favor of PAD, followed by participants younger than 46 years and reporting that spirituality was unimportant or somewhat important, being 81.8% in favor of PAD. In Hawaii, those who reported that spirituality was somewhat important or unimportant were 90.3% in favor of PAD compared to only 53.9% for those for whom spirituality was very important (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Data Were Analyzed Using Recursive Partitioning and Stepwise Forward Progression: Subgroups Identified as Being Supportive of Physician-Assisted Death

| California, n = 1095 | Hawaii, n = 819 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-group | % PAD support | Subgroup | % PAD support |

| Religion/Faith/Spirituality is very important, and age ≥46 years | 87.8 | Religion/Faith/Spirituality is somewhat important or unimportant | 90.3 |

| Religion/Faith/Spirituality is somewhat important or unimportant, and age <46 years | 81.8 | Religion/Faith/Spirituality is important, age ≥37 years | 80.3 |

| Religion/Faith/Spirituality is important, and age <46 years | 62.6 | Religion/Faith/Spirituality is important, age <37 years | 62.6 |

| Religion/Faith/Spirituality is very important | 54.1 | Religion/Faith/Spirituality is very important | 53.9 |

Stepwise Forward Regression Score calculation for individual participants:

California participant score = 2.45–0.739 × Faith +0.0148 × Age − Agemean;

California participant Agemean = 51.13.

Hawaii participant score = 2.87 − 0.930 × Faith +0.0129 × Age − Agemean;

Hawaii participant Agemean = 46.06.

Discussion

This study is the first study done to compare multi-ethnic attitudes toward PAD in California and Hawaii. It shows that spirituality and age are primary influencers of attitudes toward PAD. Older participants with lower self-reported levels of spirituality were most likely to favor PAD. We could not detect any significant gender or ethnic differences. It is not surprising that older adults are more favorably disposed toward PAD in California and Hawaii. There were 122 lethal prescription recipients in Oregon in 2013.17 Of the 71 patients who used the lethal prescription to experience PAD, 69% were older adults with a median age of 71 years (41–96 years). In reviewing the 752 persons who died using the Oregon Death With Dignity Act in the period of 1998–2013,18 217 were young-old (65–74 years), 206 were mid-old (75–84 years), and 93 were old-old (≥85 years) patients.

A large multi-national study19 showed that people who reported to be very religious were less in favor of suicide. Attitudes toward suicide have been negative among most faith traditions.20 The act of deliberately hastening death is not supported by most religions. The Exodus 20:13 is cited in the Jewish and Christian tradition as the basis of condemning suicide. However, one study21 notes that suicide per se is neither condemned nor approved in the Bible. Islam also opposes suicide19,22 as do other religions. Thus, it is not surprising that in our study participants who reported faith to be most important to them were least in support of PAD.

In an effort to distinguish the act of hastening death to mitigate suffering by a terminally ill person in the last six months of life from suicide in any other context (which is often due to underlying mental health issues), some in the medical community have moved away from the term “physician-assisted suicide” to “physician-assisted death.” In fact, the death certificates for those who die under the provision of the California Aid-in-Dying law will list the underlying terminal illness as the cause of death and thus should not affect the patient's life insurance policy. While this may make PAD a more palatable option to some terminally ill persons, it is likely that others will be ethically opposed to it.

California is the first minority-majority state where the aid-in-dying law has been implemented. It will be important to track the ethnic background of terminally ill patients requesting PAD and to determine to what extent faith/religion/spirituality influences these requests. It will also be important to determine to what extent the ethnic patients who request PAD actually utilize the lethal prescription to hasten their death. In reviewing the Oregon data for 1998–2013,18 only one AA, five HA, and eight Asians have utilized PAD. Oregon has a predominantly non-Hispanic white population with only 12.5% Hispanic, 2% African American, and 4.3% Asian. In stark contrast, California has 38.6% Hispanic, 6.5% AA, and 14.4% Asian.23

Laws such as the California End-of-life Option Act may provide an option and hopefully a sense of autonomy,24 control, and solace to those terminally ill patients who are experiencing intractable and refractory suffering despite maximal palliation. Only a small sliver25,26 of the population will be eligible for the End-of-life Option Act and of those eligible, only a portion are likely to utilize this option, and no one ethically opposed would likely do so. For example, of the 34,160 Oregonians who died in 2014,27 only 155 received a lethal prescription and 105 utilized it. Thus, even in Oregon, where the Death With Dignity Act has been in effect since 1997, only 0.3% of patients who died in 2014 utilized PAD as the way to alleviate intractable suffering at the end of life.

The California End-of-life Option Act (SB 128) and others like it are not going to alleviate suffering of most terminally ill patients. According to this Act, a terminally ill adult California resident with intact decisional capacity has the right to request her/his attending physician for an “aid-in-dying” drug prescription. Two physicians must confirm that the patient has an incurable and irreversible disease and will likely die within six months. The terminally ill patient must make three requests to a physician: two verbal requests 15 days apart and a written request attested by two witnesses. If patients cannot verbalize their request due to inability to speak, it is not clear that they will be eligible for PAD. Patients with cognitive impairment will not be eligible to request the lethal prescription. If patients are decisional at the time of request but later lose their decisional capacity, they may not be allowed to ingest the medication as it is illegal to receive any assistance to ingest the medication. Given all these complex provisions, this law will impact only a tiny fraction of seriously ill patients. However, it will most certainly impact clinical practice. As more states pass aid-in-dying laws, many Americans, whether or not they are eligible for it, will likely broach this sensitive topic with their doctors for fear of intractable suffering at the end of life. If doctors are not skilled at responding to this sensitive issue, they risk further compounding patient suffering.

Due to a national shortage of palliative subspecialists, most seriously ill patients will receive care from their primary care doctors and hospitalists. Data28–30 show that seriously ill patients suffer tremendously due to unmet bio-psycho-socio-spiritual care needs during all stages of their illness trajectory. No patient moves from a state of “zero suffering” to “intractable suffering” overnight. For many, their suffering is undertreated or untreated and escalates over days, weeks, months, and even years. Some reach an intractable point of profound distress. Most of this suffering can be effectively alleviated31–33 if patients receive meticulous symptom assessment and management from a provider they know and trust. In fact, trusted primary care providers are best positioned to mitigate their patient's symptoms and help them navigate complex end-of-life decisions. With a combination of excellent symptom management and skillful communication from the time of diagnosis of serious illness, we can prevent suffering from escalating to a point where patients are in terrible distress and forced to contemplate extreme measures such as PAD.

Currently, most34,35 doctors are not trained in pain and symptom management. Most doctors also struggle35 to conduct effective end-of-life (EOL) conversations with all patients and especially with those whose ethnicity is different from their own. Policy changes must be made to ensure that all primary care providers, generalists, and hospitalists get ongoing training36,37 to manage the multi-dimensional care needs of the millions of seriously ill Americans without allowing their suffering to escalate unchecked and become intractable.38

When faced with a terminally ill patient who is requesting aid in dying, doctors must avoid responding in a simplistic binary manner. Instead, it is imperative that all doctors become skilled at systematically exploring the multiple facets of suffering, the patient's specific situation, and the underlying concerns and experiences that have resulted in a request for hastening death. A careful assessment of the patient's mental health status is important as is assessment of the social support systems and family structure. Aggressive and prophylactic management of distressing symptoms is critical to preventing patients from reaching a depth of suffering at which they feel that PAD is their only recourse. In a diverse state such as California (which is a minority-majority state), we stress that requests from diverse patients have to be approached with great cultural sensitivity.

Our study is unique as it a large study that compares attitudes from two diverse states, one where PAD is currently legal (California) to one where it is currently not (Hawaii). We have recruited a large number of diverse participants from both states. It is important to note that our data show that Hawaii residents are very similar to California residents in being supportive of PAD. Within the Hawaii cohort, we have recruited 77 Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders and determined that a majority of them in our study support PAD. The Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders are an underserved racial minority population and our study is unique in being able to explore their attitudes toward PAD.

There are several limitations to the current study. Although being a large study, it is a convenience sample and this limits the generalizability of the findings. Another limitation is that this study was conducted online and in English, and thus limits participation to people with limited English proficiency and technical literacy. While the recent Pew Center data39 show that 85% of Americans are now online, there is definitely a selection bias in terms of participants who complete online surveys. Finally, we also wish to point out that PAD, as it is currently operationalized in the states of Oregon, Washington, Vermont, and California, pertains to the practice by which a willing physician may prescribe a lethal medication for a qualifying terminally ill patient to self-administer orally. In an effort to gain a better understanding of the underlying sentiment beyond the confines of the current legal practices, we chose to use the verbiage in the 2012 Massachusetts Ballot Measure question as it addresses a broader range of practices related to hastening death.

Conclusion

This study shows that in the ethnically diverse states of California and Hawaii, faith/religion/spirituality and age are major influencers of attitudes toward PAD and not ethnicity and gender. Even in the subgroups least supportive of PAD, the majority supports PAD. Larger, more-generalizable studies should be conducted to confirm the attitudinal patterns we identified. These attitudes may change as participants get older and as they have life experiences related to death and dying, and thus, large longitudinal studies are warranted. There is also an urgent need for early institution of palliative care for all seriously ill persons to mitigate suffering and promote dignity40,41 throughout the illness continuum.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Dr. Periyakoil's time is funded by NIMHD grant R25MD006857.

References

- 1.Espino DV, Macias RL, Wood RC, et al. : Physician-assisted suicide attitudes of older Mexican-American and non-Hispanic white adults: Does ethnicity make a difference? J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:1370–1375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koenig HG, Wildman-Hanlon D, Schmader K: Attitudes of elderly patients and their families toward physician-assisted suicide. Arch Intern Med 1996;156:2240–2248 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Craig A, Cronin B, Eward W, et al. : Attitudes toward physician-assisted suicide among physicians in Vermont. J Med Ethics 2007;33:400–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Emanuel LL: Attitudes and desires related to euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide among terminally ill patients and their caregivers. JAMA 2000;284:2460–2468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bachman JG, Doukas DJ, Lichtenstein RL, et al. : Assisted suicide and euthanasia in Michigan. N Engl J Med 1994;331:812–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blendon RJ, Szalay UR, Knox RA: Should physicians aid their patients in dying? The public perspective. JAMA 1992;267:2658–2862 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duffy SA, Jackson FC, Schim SM, et al. : Racial/ethnic preferences, sex preferences, and perceived discrimination related to end-of-life care. J Am Geriat Soc 2006;54:150–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seidlitz L, Duberstein PR, Cox C, Conwell Y: Attitudes of older people toward suicide and assisted suicide: An analysis of Gallup Poll findings. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995;43:993–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butt ZA, Overholser JC, Danielson CK: Predictors of attitudes towards physician-assisted suicide. Omega (Westport) 2003;47:107–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lichtenstein RL, Alcser KH, Corning AD, et al. : Black/white differences in attitudes toward physician-assisted suicide. J Natl Med Assoc 1997;89:125–133 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201520160SB128 (Last accessed October9, 2015)

- 12.http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/06000.html (Last accessed October9, 2015)

- 13.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S: Applied Logistic Regression, 2nd ed New York: John Wiley and Sons, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kraemer HC: Evaluating Medical Tests: Objective and Quantitative Guidelines. Newbury Park, GA: Sage, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiernan M, Kraemer HC, Winkleby MA, et al. : Do logistic regression and signal detection identify different subgroups at risk? Implications for the design of tailored interventions. Psychol Methods 2001;6:35–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yesavage JA, Kraemer HC: Signal detection software for receiver operator characteristics. Version 5. 07 [Computer software]. 2015. www.stanford.edu.laneproxy.stanford.edu/∼yesavage/ROC.html (Last accessed October9, 2015)

- 17.http://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year17.pdf (Last accessed October9, 2015)

- 18.https://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year16.pdf (Last accessed October9, 2015)

- 19.Stack S, Kposowa AJ: Religion and suicide acceptability: A cross-national analysis. J Sci Study Relig 2011;50:289–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cook CC: Suicide and religion. Br J Psychiatry 2014;204:254–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koch HJ: Suicides and suicide ideation in the Bible: An empirical survey. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2005;112:167–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ali AY: The Holy Qur'an: Translation and Commentary. United Kingdom: IPCI–Islamic Vision, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 23.www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/RHI725214/15,06,41,00 (Last accessed October9, 2015)

- 24.Chin AE, Hedberg K, Higginson GK, Fleming DW: Legalized physician-assisted suicide in Oregon—the first year's experience. N Engl J Med 1999;340:577–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quill TE, Cassel CK: Professional organizations' position statements on physician-assisted suicide: A case for studied neutrality. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:208–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sullivan AD, Hedberg K, Fleming DW: Legalized physician-assisted suicide in Oregon—the second year. N Engl J Med 2000;342:598–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.https://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year17.pdf (Last accessed October9, 2015)

- 28.Teno JM, Freedman VA, Kasper JD, et al. : Is care for the dying improving in the United States? J Palliat Med 2015;18:662–666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singer AE, Meeker D, Teno JM, et al. : Symptom trends in the last year of life from 1998 to 2010: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:175–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohlwes RJ, Koepsell TD, Rhodes LA, Pearlman RA: Physicians' responses to patients' requests for physician-assisted suicide. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:657–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bascom PB, Tolle SW: Responding to requests for physician-assisted suicide: “These are uncharted waters for both of us…”. JAMA 2002;288:91–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Daniels ER, Clarridge BR: Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: Attitudes and experiences of oncology patients, oncologists, and the public. Lancet 1996;347:1805–1810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Back AL, Starks H, Hsu C, et al. : Clinician-patient interactions about requests for physician-assisted suicide: A patient and family view. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1257–1265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Periyakoil VS, Neri E, Fong A, Kraemer H: Do unto others: Doctors' personal end-of-life resuscitation preferences and their attitudes toward advance directives. PLoS One 2014;9:e98246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Periyakoil VS, Neri E, Kraemer H: No easy talk: A mixed methods study of doctor reported barriers to conducting effective end-of-life conversations with diverse patients. PLoS One 2015;10:e0122321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emanuel EJ, Fairclough D, Clarridge BC, et al. : Attitudes and practices of U.S. oncologists regarding euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide. Ann Intern Med 2000;133:527–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Physician-assisted suicide: Toward a comprehensive understanding. Report of the Task Force on Physician-assisted Suicide of the Society for Health and Human Values. Acad Med 1995;70:583–590 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quill TE, Lo B, Brock DW: Palliative options of last resort: A comparison of voluntarily stopping eating and drinking, terminal sedation, physician-assisted suicide, and voluntary active euthanasia. JAMA 1997;278:2099–2104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zichuhr K: Who's not online and why. PEW Research Center; www.pewinternet.org/2013/09/25/whos-not-online-and-why/ (Last accessed October9, 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 40.Periyakoil VS, Noda AM, Kraemer HC: Assessment of factors influencing preservation of dignity at life's end: Creation and the cross-cultural validation of the preservation of dignity card-sort tool. J Palliat Med 2010;13:495–500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Periyakoil VS, Kraemer HC, Noda A: Creation and the empirical validation of the dignity card-sort tool to assess factors influencing erosion of dignity at life's end. J Palliat Med 2009;12:1125–1130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]