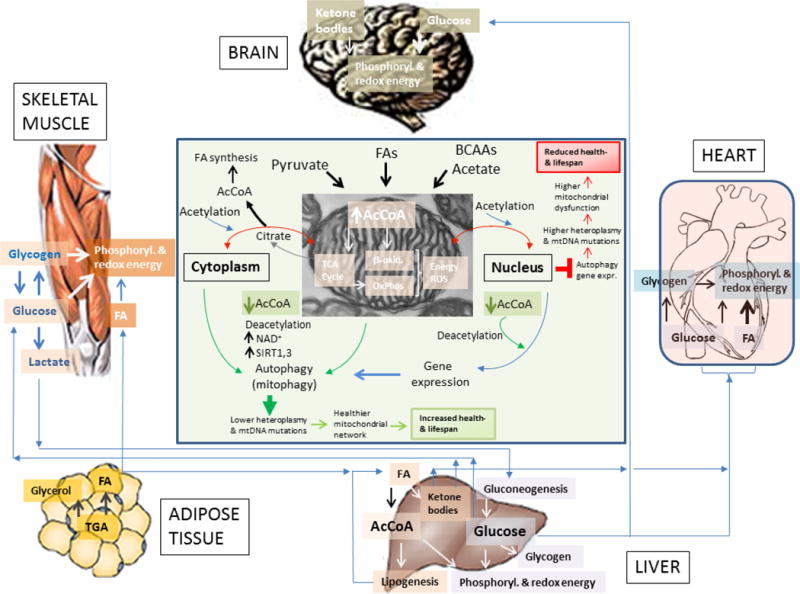

Figure 4. Substrates fuel interrelationships between main body organs, mitochondria and the epigenome.

Depicted are the differential uses of glucose and fatty acids (FAs) by the brain, muscle (cardiac and skeletal), liver and adipose tissue. As shown, the liver appears as a main provider of glucose and FAs for muscle and brain. Adipose tissue provides FAs to the liver; the skeletal muscle can also supply lactate to the liver where it is utilized for gluconeogenesis, especially in the early fed state, when the liver continues in ketogenic and gluconeogenic modes.

Displayed is the mitochondrial supply of AcCoA, the main acetyl donor that via its nucleo-cytoplasmic pools determine the autophagic response in mammals [168] and, with a few difference, in yeast as well [162]. The scheme at the center emphasizes that AcCoA excess (red right) or decrease (green bottom) will preclude or stimulate autophagy and gene expression, respectively; decreased autophagy will favor higher mtDNA mutations and heteroplasmy driving accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria that, in the long-term, will reduce health- and lifespan (red box, top right). Opposite changes will occur under a more balanced AcCoA supply (green box, bottom). Hypothetically, healthy and nutritionally well-adjusted lifestyle, including physical activity or exercise training, would favor balanced energy supply and demand in concert with mitochondrial fusion/fission-driven morphological changes, turnover (mitophagy, biogenesis) and proper energy-redox function [201]. The interplay between these processes would determine not only the overall functionality of the mitochondrial network but also the integrity of the mitochondrial genome [4, 78].