Highlights

-

•

Novel reconstructive option for complex hard and soft tissue defects.

-

•

Beavertail modification provides additional central bulk to restore larger defects.

-

•

Limited donor site morbidity encourages early post-operative mobilisation.

-

•

Reduced operative time limits physiological stress under general anaesthetic.

Keywords: Case report, Radial forearm flap, Osseocutaneous, Novel technique

Abstract

Introduction

Complex hard and soft tissue defects produced as a result of ablative resection of head and neck malignancy can represent a reconstructive challenge, especially when patients are medically compromised. PRESENTATION OF CASE: We present the case of 72-year-old women presenting with an oral squamous cell carcinoma of the right floor of mouth invading the right mandible. Surgical management of the disease required ablative surgery with complex free tissue transfer reconstruction to provide restoration of form and function. Potential reconstructive options were limited by her medical comorbidities and poor vessel patency in the lower limbs, requiring novel thinking and adaptation of established techniques.

Discussion

We describe the first reported use of an osseofasciocutaneous radial forearm flap with a ‘beavertail modification’ to provide a single and combined reconstructive option to reconstruct a complex hard and soft tissue defect.

Conclusion

This novel free-flap technique adds to the reconstructive armamentarium of the head and neck surgeon.

1. Introduction

Complex hard and soft tissue defects produced as a result of resection of head and neck malignancy can represent a reconstructive challenge. It is vital that both the form and function of the reconstruction are carefully considered to provide the best possible chance of making a good recovery, providing restoration of quality of life after curative treatment. As highlighted by this case, accomplishing these reconstructive goals can be challenging in the presence of comorbidity such as ischaemic heart disease and peripheral vascular disease. This case was managed by an experienced consultant head and neck surgeon within a specialist tertiary hospital, and has been reported in compliance with the Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) Guidelines [1].

2. Case report

A 72-year-old woman was referred to the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery by her dental practitioner with a two-month history of a painful ulcerated lesion on the right floor of mouth, neck pain and dysphagia. At examination this lesion was three centimetres in diameter, indurated and exophytic. An urgent incisional biopsy confirmed poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. Staging magnetic resonance imaging revealed a soft tissue lesion measuring 2.8 × 1.5 × 2.7 centimetres in the right anterior floor of mouth and extending into the ventral tongue and mandible, as well as multiple suspicious ipsilateral Level Ib cervical lymph nodes. Marrow signal change was evident adjacent to the tumour mass. Computed tomography (CT) of the mandible confirmed erosion of the alveolar crest of the mandible consistent with bone invasion. CT of the thorax displayed evidence of chronic inflammatory lung disease but no evidence of metastasis. On the basis of involvement of the extrinsic muscles of the tongue, bony invasion of the mandible and multiple ipsilateral level Ib cervical lymph nodes, the disease was staged clinically as T4a N2b M0.

Risk factors for oral squamous cell carcinoma included an 85-pack year history of smoking and a long history of excess alcohol consumption. Medically, she had multiple cardiovascular comorbidities including poorly controlled essential hypertension, ischaemic heart disease and atrial fibrillation for which she was taking warfarin. Echocardiogram revealed moderate mitral stenosis and regurgitation as well bilateral atrial dilatation and tricuspid regurgitation. Anaesthetic and cardiology opinions placed her at increased risk of complications from prolonged general anaesthesia.

Following discussion within the multidisciplinary head and neck cancer team, this lady was offered treatment for cure. This was planned to involve primary surgical resection and reconstruction, followed by adjuvant radiotherapy (+/− concurrent chemotherapy) because of evidence of local bony invasion and neck metastatic spread. Surgical management included bilateral neck dissection, resection of the primary tumour with segmental resection of the right mandible, floor of mouth and right tongue and reconstruction using free tissue transfer.

The choice of which specific reconstructive option was critical when considering this patient’s multiple complex comorbidities and consequent increased risks of prolonged general anaesthesia and major surgery.

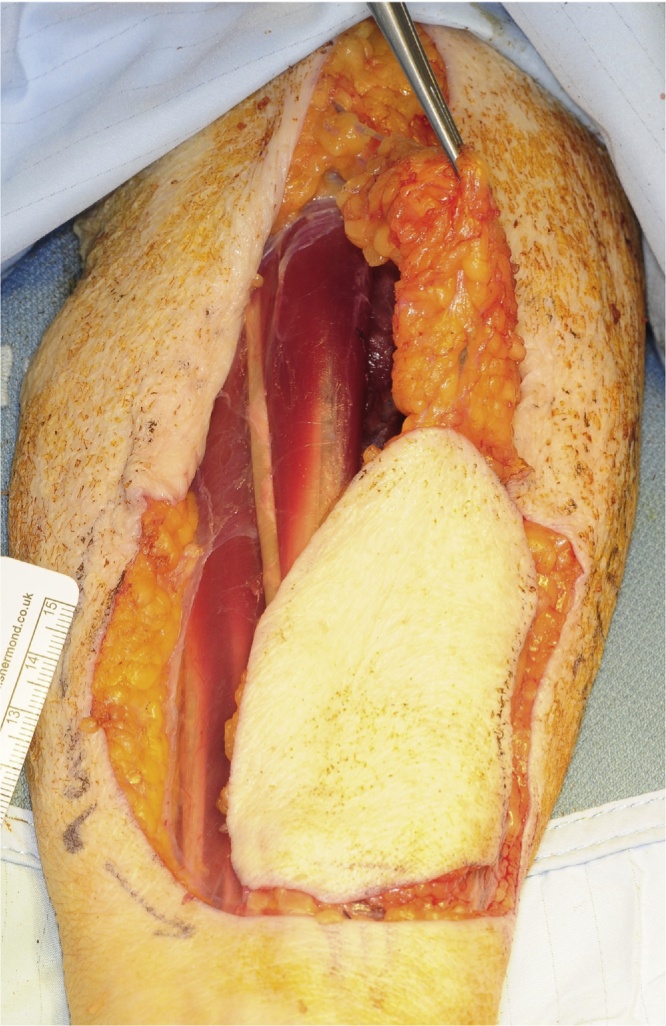

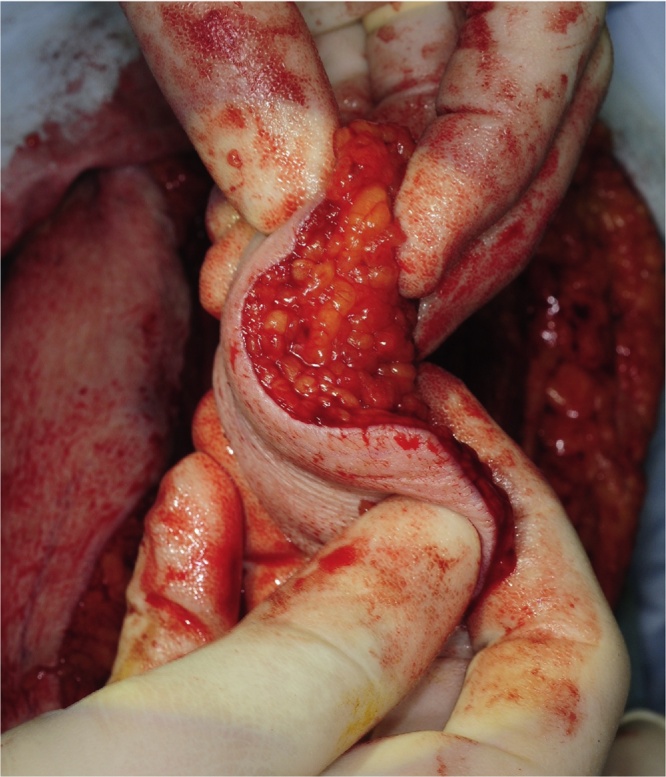

The most suitable reconstructive option was considered to be an osseocutaneous radial forearm free flap. This option allowed restoration of bony continuity of the mandible, as well as a soft pliable skin paddle to reconstruct the floor of mouth and tongue as a single reconstructive flap. However, one of the often-quoted advantages of the radial flap flap (thinness) was less ideal in this case which required some bulk to reconstruct a relatively large defect. Central flap volume is required to restore swallow by providing bulk centrally to allow the suprahyoid musculature to propel the food bolus superiorly and posteriorly against the hard palate. Additional bulk for this flap was provided by adapting a concept previously described by Seikaly [2] by utilising a beavertail modification. This technique includes proximal fat and fascia (the beavertail; shown in Fig. 1) in addition to the fasciocutaneous component which can be dissected free from the vascular pedicle and folded under the skin paddle to provide additional bulk to this normally thin flap (Fig. 2). This combination of an osseocutaneous radial forearm flap and use of a beavertail modification to provide additional bulk to reconstruct a complex hard and soft tissue defect has not been described in the literature.

Fig. 1.

Elevation of the radial forearm fasciocutaneous element with proximal subcutaneous fat and fascia (the beavertail).

Fig. 2.

The beavertail is rolled under the skin paddle demonstrating increased flap volume achieved.

Tumour ablation resulted in a bony defect extending from the left parasymphysis to the right ramus of mandible (Fig. 3) which was reconstructed with the segment of osteotomised radial bone held with a carefully contoured preformed titanium reconstruction plate (Fig. 4). The fasciocutaneous portion was used to reconstruct the large soft tissue defect of the right anterior floor of mouth and ventral tongue.

Fig. 3.

Resulting complex defect anterior floor of mouth, ventral tongue and mandible.

Fig. 4.

Osteotomised radial bone forming the neomandible, held by titanium reconstruction plate.

This lady made a steady post-operative recovery and was discharged from hospital after 31 days. Her swallowing function was assessed as excellent with no dysphagia, owing to the added bulk of the free flap, and her weight remained stable prior to commencement of radiotherapy. Our speech and language team assessed her post-operative speech intelligibility as excellent. Histopathological examination of the primary tumour and cervical nodes confirmed the clinical staging of T4a N2b M0. She went on to have the prescribed course of radiotherapy lasting 6.5 weeks (66 Gy in 33 fractions) which she tolerated remarkably well.

3. Discussion

Microvascular free tissue transfer has become the primary choice for reconstruction after oncological resection in the head and neck. The radial forearm free flap (RFFF), first described over three decades ago [3], is particularly popular because of ease of harvest, versatility, minimal morbidity and a long pedicle with a large external diameter [4,5]. The inclusion of a segment of radial bone as part of the flap was first described by Biemer in 1983 to reconstruct the thumb [6]. Soutar et al. later described using the an osteocutaneous radial flap to reconstruct a mandibular bony defect [7] and this is now a useful reconstructive option in selected cases [8].

Alternative options for reconstruction of mandibular bony defects most commonly include the fibula free flap or a segment of iliac crest bone based on the deep circumflex iliac artery (DCIA free flap). Owing to the voluminous skin paddle, osteomyocutaneous DCIA flaps are often considered too bulky for intraoral reconstruction [9,10]. Many surgeons now consider the fibula free flap as the optimal reconstructive option for composite segmental mandibular defects [11]. However, this option was considered not possible for this patient due to lower limb peripheral vascular disease evident by symptoms and on imaging. The fibula flap provides a relatively thick skin paddle which is less suitable for certain situations [12] such as reconstruction of the tongue and floor of mouth. The fibula flap is also not easily customised to provide differential soft tissue bulk.

No established single free flap was considered to have the ideal characteristics to reconstruct this patient. The use of two simultaneous free flaps is an option for reconstruction of large complex defects [13] and also to allow the independent selection of ideal osseous or soft tissue elements [14]. This was considered to be not appropriate for this patient as the use of two free flaps would have significantly increased operation time, risk of complications and donor site morbidity.

The osteocutaneous radial forearm free flap is generally reserved for elderly patients to support early mobilisation in the post operative period [15], due to reduced donor site morbidity when compared to harvesting a fibula flap. The osseocutaneous radial flap is also considered useful in a number of other circumstances; when there is appreciable peripheral vascular disease (as the radial artery is usually relatively unaffected [16], [17]), when there is other serious comorbidity, and as a salvage flap when other reconstructive options have been exhausted [8].

4. Conclusion

The osseocutaneous radial forearm flap with beavertail modification is a novel reconstructive option, which provides sufficient bulk of bone and a soft tissue component which can be of variable thickness. Additional advantages of reduced surgical time and early post-operative mobilisation are likely to be most beneficial in elderly or medically compromised patients.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

References

- 1.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P. A protocol for the development of reporting criteria for surgical case reports: the SCARE statement. Int. J. Surg. 2016;27:187–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.01.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seikaly H., Reiger J., O’Connell D., Ansari K., AlQahtani K., Harris J. Beavertail modification of the radial forearm free flap In base of tongue reconstruction: technique and functional outcomes. Head Neck. 2009;21:213–219. doi: 10.1002/hed.20953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang G., Chen B., Gao Y., Liu X., Li J. Forearm free skin transplantation. Natl. Med. J. China. 1981;61:139. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaltman J.M., a McClure S., a Lopez E., Pedroletti F. Closure of the radial forearm free flap donor site defect with a full-thickness skin graft from the inner arm: a preferred technique. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012;70:1459–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans G.R.D., Schusterman M.A., Kroll S.S., Miller M.J., Reece G.P., Robb G.L. The radial forearm free-Flap for head and neck reconstruction – a review. Am. J. Surg. 1994;168:446–450. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80096-0. <Go to ISI>://A1994PQ61700019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biemer E., Stock W. Total thumb reconstruction: a one-stage reconstruction using an osteo-cutaneous forearm flap. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 1983;36:52–55. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(83)90011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soutar D.S., Scheker L.R., Tanner N.S.B., McGregor I.A. The radial forearm flap: a versatile method for intra-oral reconstruction. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 1983;36:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(83)90002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Avery C.M.E. Review of the radial free flap: still evolving or facing extinction? Part two: osteocutaneous radial free flap. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2010;48:253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2009.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urken M., Cheney M., Sullivan M., Biller H. Raven Press; New York: 1990. Atlas of Regional and Free Flaps for Head and Neck Reconstruction. [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Brien B., Morrison W. Churchill-Livingstone; Edinburgh: 1987. Reconstructive Microsurgery. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Villera D., Futarn N. The indications and outcomes in the use of osteocutaneous radial forearm free flap. Head Neck. 2003;25:475–481. doi: 10.1002/hed.10212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzalez-Castro J., Petrisor D., Ballard D., Wax M.K. The double-barreled radial forearm osteocutaneous free flap. Laryngoscope. 2015:340–344. doi: 10.1002/lary.25388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wei F., Demirkan F., Chen H., Chen I. Double free faps in reconstruction of extensive composite mandibular defects in head and neck cancer. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1999;103:39–47. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199901000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mo K.W.L., Vlantis A., Wong E.W.Y., Chiu T.W. Double free flaps for reconstruction of complex/composite defects in head and neck surgery. Hong Kong Med. J. 2014;20:279–284. doi: 10.12809/hkmj134113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Genechten M.L.V., Batstone M.D. The relative survival of composite free flaps in head and neck reconstruction. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2016;45:163–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2015.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Müller-Richter U.D.A., Driemel O., Mörtl M., Schwarz S., Zorger N., Wagener H. The value of Allen’s test in harvesting a radial forearm flap: correlation of ex-vivo angiography and histopathological findings. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2008;37:672–674. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Bree R., Quak J.J., Kummer J.A., Simsek S., Leemans C.R. Severe atherosclerosis of the radial artery in a free radial forearm flap precluding its use. Oral Oncol. 2004;40:99–102. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(03)00133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]