Abstract

Evans syndrome (ES) is a rare hematological disease characterized by autoimmune hemolytic anemia, immune thrombocytopenia, and/or neutropenia, all of which may be seen simultaneously or subsequently. Thrombotic events in ES are uncommon. Furthermore, non-ST segment-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) during ES is a very rare condition. Here, we describe a case of a 69-year-old female patient presenting with NSTEMI and ES. Revascularization via percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was scheduled and performed. Hemopericardium and cardiac tamponade occurred 5 h after PCI, and urgent pericardiocentesis was performed. Follow-up was uneventful, and the patient was safely discharged. Early recognition and appropriate management of NSTEMI is crucial to prevent morbidity and mortality. Coexistence of NSTEMI and ES, which is associated with increased bleeding risk, is a challenging scenario and these patients should be closely monitored in order to achieve early recognition and treatment of complications.

Keywords: Evans syndrome, Myocardial infarction, Hemopericardium

1. Introduction

Evans syndrome (ES) is a rare hematological disease characterized by autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA), immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), and/or neutropenia, all of which may be seen simultaneously or subsequently with no known underlying etiology.1 Despite various treatment options, ES is associated with significant morbidity and mortality rates due to chronic and repetitive nature of the disease.2

Antibodies against erythrocytes, platelets, and neutrophils are present in ES. While some of the antibodies are directed against a base protein of the Rh blood group and cause red blood destruction, most of them are directed against the platelet GPIIb/IIIa.3 Although most of the cases are classified as primary (or idiopathic), ES has been associated with several conditions including systemic lupus erythematosus, lymphoproliferative disorders, and primary immunodeficiency diseases as secondary.2 Thrombotic events are rarely seen in ES; thus, anecdotal case reports exist mostly as venous thrombosis.4, 5, 6, 7 In another study including series of 68 patients, 6 patients (21%) developed cardiovascular events during a follow-up of 4.8 years. One patient developed myocardial infarction, 4 developed acute coronary syndrome, and 1 developed stroke. 21% had cardiovascular events and 16 patients died.8

The present case exhibits coexisting ES and non-ST segment-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) complicated with hemopericardium, a phenomenon which has been reported as a very rare condition.

2. Case report

A 69-year-old female patient was admitted to emergency room for chest pain with increasing intensity for the past 1 week. She had history of hypertension treated with metoprolol (50 mg/day) for 10 years and umbilical hernia surgery 5 years ago. On examination, she was sweating, had mild dyspnea and paleness. Her blood pressure was 135/82 mmHg and heart rate was 102 beats/min with a blood saturation of 96% in room air. Physical examination was unremarkable except the relapsed umbilical hernia. She was a non-smoker and did not consume alcohol. Her 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) showed ST-segment depression in leads V3–V6.

Echocardiographic examination revealed a left ventricular ejection fraction of 55% with hypokinesia in inferior and posterior segments, left ventricular hypertrophy, and moderate mitral regurgitation.

Initial blood tests showed white blood cell count (WBC) 2.86 × 103/μL (normal range 4.4–11.3 × 103/μL), hemoglobin 6 g/dL (normal range 11.7–16.1 g/dL), platelet count 1 × 103/μL (normal range 152–396 × 103/μL), urea 35 mg/dL (normal range 16.6–48.5 mg/dL), creatinine 1 mg/dL (normal range 0.5–0.9 mg/dL), glucose 83.5 mg/dL (normal range 74–109 mg/dL), sodium 130 mmol/L (normal range 136–145 mmol/L), potassium 4.3 mmol/L (normal range 3.5–5.1 mmol/L), prothrombin time 13.2 s (normal range 11.5–15 s), activated partial thromboplastin time 31 s (normal range 26–32 s), and international normalized ratio 1.0 (normal range 0.8–1.2). Repeated complete blood count (CBC) provided similar results. Peripheral smear test was unremarkable. We detected levels of cardiac enzymes as follows: CK 157 (normal range 26–192 U/L), CK-MB 11 (normal range <7.2 μg/L), and Tn-I 0.29 μg/L (normal range <0.023 μg/L).

The patient received immediate treatment with a loading dose of clopidogrel (300 mg) and ASA (300 mg), and was transferred to our coronary intensive care unit (CICU) with the diagnosis of acute NSTEMI and pancytopenia. Intravenous nitroglycerin infusion was initiated for the relief of her chest pain. She also received 100 mg/day metoprolol and 40 mg/day statin via oral route.

Hematology department was consulted for the patient, and further tests showed high levels of LDH 366 U/L (normal 135–214 U/L), low levels of haptoglobulin <10 (normal 30–200 mg/dL), and positive Direct and Indirect Coombs tests. ES was diagnosed in this patient with respect to neutropenia, AIHA, and thrombocytopenia. Two units of packed red blood cells and 8 units of thrombocyte suspension were transfused. Intravenous methyl prednisolone at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) 1 mg/kg/day were administered for 2 days.

On the second day of admission, CBC revealed WBC 9.81 × 103/μL, hemoglobin 7.2 g/dL, and platelet count 52 × 103/μL. Again, 2 units of packed red-blood cells were transfused.

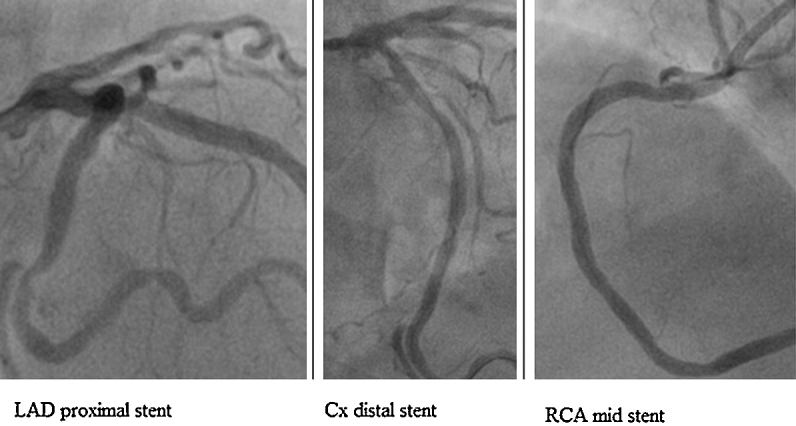

Because of refractory angina despite optimal medical treatment, urgent conventional coronary angiography (CCA) was scheduled and performed with radial access with 60 U/kg unfractionated heparin (UFH). CCA demonstrated 99% obstruction in the proximal segment of left anterior descending artery (LAD), 80% obstruction in distal circumflex artery (Cx), and 99% obstruction in middle right coronary artery (RCA) (Fig. 1). Complete revascularization was achieved with 3 bare-metal stents (3.0 mm × 24 mm Liberte for LAD, 2.5 mm × 16 mm Liberte for Cx, and 2.75 mm × 16 mm Liberte for RCA) (Fig. 2). After removing the radial sheath, a compression device was placed on the wrist and the patient was transferred to CICU for follow-up.

Fig. 1.

Coronary angiographic images of the patient.

Fig. 2.

Coronary angiographic images of the patient after revascularization.

Five hours after the procedure, the patient developed severe chest pain with sudden onset, and her control ECG was unremarkable. After a short while, her blood pressure dropped to 85/50 mmHg, and bedside echocardiography revealed pericardial effusion with cardiac tamponade.

An amount of 400 mL hemorrhagic pericardial fluid was removed by bedside pericardiocentesis. Hemodynamic status of the patient rapidly improved, and her chest pain resolved. Analysis of the pericardial fluid confirmed hemopericardium. During the 2 days follow-up, no additional fluid was drained from the catheter. After confirmation of absence of residual pericardial effusion, the sheath in the pericardial cavity was removed. Tests for etiological investigation of pancytopenia revealed normal results for antinuclear antibodies, antiphospholipid IgG and IgM, anticardiolipin IgG and IgM, viral markers, folic acid, B12 vitamin, and thyroid function tests. Thoracoabdominal computed tomography was performed for malignancy scanning. No solid tumoral infiltrations or pathological lymph nodes were detected. A diagnosis of ES was concluded by hematologists based on ruling out other possible etiologies.

The patient was discharged on the sixth day of admission with laboratory findings showing a blood count with WBC 9.81 × 103/μL, hemoglobin 9.1 g/dL, platelet count 55 × 103/μL, and a prescription of aspirin (100 mg po daily), clopidogrel (75 mg po daily), and methyl prednisolone (70 mg po daily). She was asymptomatic on her follow-up visit at 1 month. Her blood tests revealed WBC 6.7 × 103/μL, hemoglobin 12.6 g/dL, and platelet count 123 × 103/μL. She remains asymptomatic on her follow-up visits.

3. Discussion

Diagnosis of ES is established by ruling out similar conditions like systemic lupus erythematosus, lymphoproliferative disorders, primary immunodeficiency, and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Careful analysis of the tests and examination is crucial for avoiding misdiagnosis.8 Peripheral blood smear is substantial for diagnosis of both lymphoproliferative disorders and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Bone marrow biopsy might be necessary for diagnosis when findings of peripheral blood smear are consistent with lymphoproliferative disorders.9

Since ES is a rare autoimmune disorder, there are no systematic or randomized studies for ES treatment, and current treatment is mainly based on AIHA and ITP therapies. First-line treatment commonly consists of glucocorticoids and/or IVIG. Current practice institutes prednisolone (1–2 mg/kg/day) and/or IVIG (0.4 g/kg/d for 4 days) in cases of remission or ineffective prednisolone treatment. Immunosuppressive agents or splenectomy are recommended as second-line therapy for patients with relapse or worsening health condition despite first-line therapy.10

NSTEMI is the most common form of acute coronary syndromes, and also associated with high mortality rates. Early treatment is crucial for the favorable prognosis of the disease.11

In conditions associated with high bleeding risk as seen in our case, medical treatment and interventional treatment are both challenging. In order to minimize bleeding risk in our patient, we initiated thrombocyte transfusion, corticosteroid therapy, and IVIG for two days and then scheduled the patient for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Moreover, we preferred radial access for CCA and PCI to minimize the bleeding risk. The guidewire (ChoICE Floppy Guide Wire, Boston Scientific), which was used to cross coronary lesions, was not stiff. Bare metal stents were preferred to avoid long-term dual antiplatelet therapy, and thus increased bleeding risk. NSTEMI treatment includes antiaggregant and anticoagulant drugs; however, in daily practice, hemopericardium is not an expected complication in patients receiving those drugs and undergoing PCI. In our patient, although the PCI procedure was uneventful and revascularization was achieved successfully, cardiac tamponade occurred due to hemopericardium 5 h after the procedure. Prompt recognition of hemodynamic compromise was life-saving at this stage. It is likely that medical treatment facilitated bleeding event in this patient; however, tendency for bleeding induced by ES might have played a bigger role in the formation of a serious hemorrhagic complication such as hemopericardium. Coronary rupture induced with micro-injury in coronary artery wall by the distal tip of the guidewire during PCI combined with the bleeding disorder of the patient may have led to hemopericardium. Besides, administration of UFH during PCI to avoid thrombosis may also have contributed to hemopericardium formation. Perhaps fondaparinux could have been utilized instead of UFH in order to decrease bleeding complications.

ES most commonly presents with bleeding events; however, it may rarely present with thrombosis. Although uncommon, coexistence of ES and thrombotic events such as acute coronary syndrome is associated with high morbidity and mortality, and early reperfusion therapy is crucial in this setting. When ES is seen with a high-mortality linked condition such as acute coronary syndrome where early reperfusion (medical or interventional) is crucial, the patient should be closely monitored during the diagnostic and treatment period in order to achieve early recognition and treatment of complications.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Evans R.S., Takahashı K., Duane R.T., Payner R., Lıu C. Primary thrombocytopenic purpura and acquired hemolytic anemia; evidence for a common etiology. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1951;87:48–65. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1951.03810010058005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Savaşan S., Warrier I., Ravindranath Y. The spectrum of Evans’ syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1997;77:245–248. doi: 10.1136/adc.77.3.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright D.E., Rosovsky R.P., Platt M.Y. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 36-2013. A 38-year-old woman with anemia and thrombocytopenia. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2032–2043. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc1215972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Escher R. Extensive venous thrombosis following administration of high-dose glucocorticosteroids and tranexamic acid in relapsed Evans syndrome. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2008;19:741–742. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e32830d5ef5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yilmaz S., Oren H., Irken G., Türker M., Yilmaz E., Ada E. Cerebral venous thrombosis in a patient with Evans syndrome: a rare association. Ann Hematol. 2005;84:124–126. doi: 10.1007/s00277-004-0963-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shiozawa Z., Ueda R., Mano T., Tsugane R., Kageyama N. Superior sagittal sinus thrombosis associated with Evans’ syndrome of haemolytic anaemia. J Neurol. 1985;232:280–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00313866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Fiar F.Z., Clink H.M. Evans syndrome associated with venous thrombosis. Ann Saudi Med. 1995;15:168–170. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1995.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michel M., Chanet V., Dechartres A. The spectrum of Evans syndrome in adults: new insight into the disease based on the analysis of 68 cases. Blood. 2009;114:3167–3172. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-215368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.García-Muñoz R., Rodriguez-Otero P., Pegenaute C. Splenic marginal zone lymphoma with Evans’ syndrome, autoimmunity, and peripheral gamma/delta T cells. Ann Hematol. 2009;88:177–178. doi: 10.1007/s00277-008-0555-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norton A., Roberts I. Management of Evans syndrome. Br J Haematol. 2006;132:125–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meier P., Lansky A.J., Baumbach A. Almanac 2013: acute coronary syndromes. Heart. 2013;99:1488–1493. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]